Coming full circle. It all started in the Med. It was here in the 1930’s and 40’s that the likes of Hans Hass, Jacques-Yves Cousteau, Frederic Dumas and Phillip Tailliez pioneered scuba diving as we came to know it. Erstwhile the obvious choice for dive travelers once the Red Sea and even more exotic destinations became accessible to a wider audience, it fell somewhat out of favor. But now, it’s back on the map, the fish are back and so are the divers. Kurt Amsler gives us the lowdown on diving in what is now his backyard.

Contributed by

Wind the clock back to 1937, and we will find a young man from Austria by the name of Hans Hass spending his holiday after graduating from high school in the little town of Juan-les-Pins on the French Riviera. It was here he observed an Englishman hunting for fish underwater which seeded the inspiration that would later make him one of the greatest diving pioneers. It was also in this region that three Frenchmen from Marseilles—Jacques Cousteau, Frederic Dumas and Phillip Tailliez—who later came to be known as the “The Three Musketeers”, first started underwater hunting before experimenting with various equipment that allowed them to breathe underwater. This was how the regulator came about.

It was here, in June 1943, that what was to become arguably the most important invention in diving was first developed and tested. Jacques Cousteau describes this event as an uplifting moment in his book, The Silent World:

“On the morning of said day, I went to the station in the little town of Bandol on the French Riviera and picked up a little parcel that had been sent to me express from Paris. It contained a new promising device, the result of years of struggles and dreams: It was the automatic aqualung that Emile Gagnan and I had built together. I went back to the villa Barry where my dive-buddies Philippe Tailliez and Frederic Dumas were eagerly awaiting my return. I don’t think there have ever been any children opening a Christmas package who were quite as excited as we were when we unwrapped this first ‘Aqua Lung’. If this piece of kit was working as intended it would mean a revolution in the diving community.

“We procured a set of three medium-sized cylinders with compressed air, which were connected to a regulator the size of an alarm clock. The regulator was fitted with two hoses that were attached to a mouthpiece. Kitted up with this equipment strapped on the back, a waterproof mask of glass over the eyes and nose and rubber flippers, we wanted to undertake free and independent daring forays into the depths of the sea.

“We hurried to a sheltered bay where we could be safe from the prying eyes of bathers and the Italian soldiers from the occupational force. I checked the air pressure. The tanks contained compressed air with a pressure of 150 atmospheres. I could hardly contain my excitement and was eager to discuss the plan for the first test dive.”

The rest, as they say, is history. Of course, many other well-known names and places along the Côte d’Azur, closely tied to the evolution of diving and technology, which we now take for granted today, were in many cases conceived and first tested along these coastlines. Henry Broussard and Dimitri Rebikoff developed some of the first underwater cameras and flash units in Cannes. In Marseille, Claude Wesly and Albert Falco (who later captained the research vessel Calypso) were among the first people to spend several days in an underwater habitat on the seabed. And, of course, there is the freediving legend, Jacques Mayol, who lived in Sanary.

Places like Grand Congloué, Le Dramont and Antheor are famous for their ancient shipwrecks, while names like Port-Cros, Cavalaire, La Tour de Fondue, or Planier Island make the connoisseur divers’ mouths water. The French Riviera is also the seat of many leading brands of dive equipment: Scubapro in Antibes, AquaLung in Nice, Beuchat and Oceanic in Marseille. On the Italian side of the border, we find equally significant makes such as Mares and Cressi-Sub.

The region is also a center for skindiving, with commercial diving schools such as COMEX being based here. For many years, the world festival of underwater images was based in Antibes/Juan les Pins before moving to nearby Marseilles. Beginning as a local event over three decades ago, this annual photographic celebration is now the world’s biggest and most significant event of its kind. The highlights of the Côte d’Azur are, of course, the wrecks. Currently, many hundreds are known and about half of these are within reach of regular recreational divers. But there are so many other highlights for a diving vacation on the Côte d’Azur.

Profitez de la vie! —Enjoy life!

Surely the underwater world off the coast of southern France now looks quite different from the time the aforementioned pioneers went on their first exploratory forays into the blue realm. But for those who say that the Mediterranean has nothing more to offer, think again. Granted, you have to know the good places to experience diving adventures that do not get any better in tropical seas. Fortunately, there is now a very good infrastructure for divers in place with well-equipped dive centers from Marseille to Nice. As far as the conditions go, the wind and weather can sometimes get a bit rough and the water is a few degrees colder than in a tropical lagoon. But it is precisely these factors that make diving at the “Côte” a special experience.

Technical diving

Diving in the Mediterranean differs from diving in the topics in several ways. In the Mediterranean, the most beautiful regions are found at depths of between 20 and 40 meters. This depth already raises the bar with regards to the requirements of equipment and training. In addition, a 10-liter tank (The ubiquitous Alu80 used as a standard tank size at many resorts worldwide contains 11 liters) can only take you so far. It is not really big enough. A 15-liter tank is more appropriate.

Since the temperature of the Mediterranean decreases markedly with depth, a good 6mm to 7mm wetsuit is required in summer; while a dry suit comes in handy during the winter. Many of the most spectacular sites and wrecks are found in open water where ascending along a downline is required, so a higher level of diving experience and training is recommended. The dive centers in locations covered in this article provide excellent service and training. Descending through the blue from a buoy in open waters is nicknamed “parachuting” and can be quite fun, even if it only takes a short time to get down.

Flora and fauna

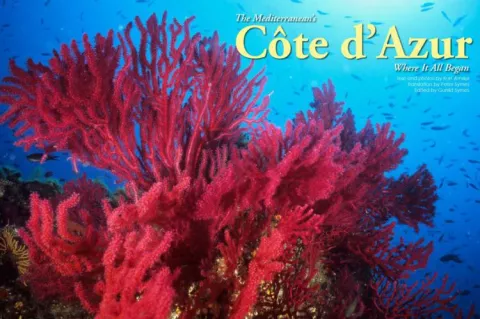

The jewels of the Mediterranean are its biodiversity and colors, but not as you know them in tropical reefs. Thanks to many protection measures and national parks in France, the abundance of fish is enormous. The colors of the underwater world are magnificent, and rocks and the wrecks are overgrown with large red and yellow gorgonians. At this point, I would advise you to always bring a lamp of at least 20 watts, even during the day. Only with illumination is it possible to appreciate the beautiful colors on the walls of canyons, grottos and caves. In these habitats, more sedentary creatures—such as moray eels, conger eels, scorpionfish, octopus and grouper (called Merou here in France)— can be seen.

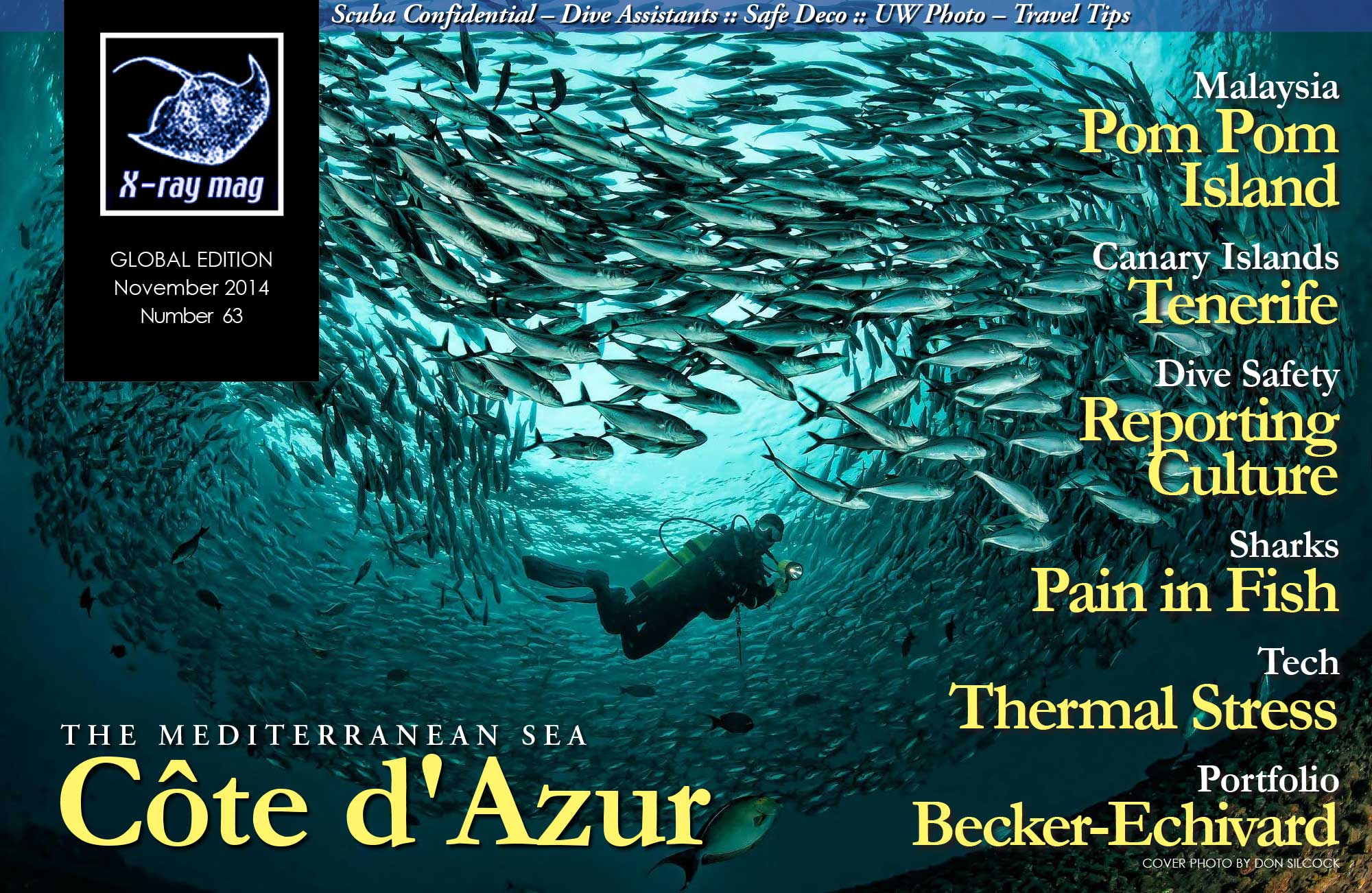

On the island of Port Cros, for example, there are places with more than 30 of these groupers. Around the red gorgonians are tilefish, which show the same light colors as their tropical relatives. In open water, you can observe large flocks of small dark-coloured swallowtails chasing mackerel and the other predatory fish. For several years, large schools of barracuda can be found in various locations. Practically hundreds of schools of fish can be found at La Gabiniere, in the National Park Port Cros. For macro fans, the Mediterranean is a never-ending, and always exhilarating hunting area. Provided you have good eyes, you can spot various kinds of nudibranchs in all colors and shapes. The yellow anemones, the white polyps of red precious coral and the various tubeworms never fail to make photographers’ hearts beat a little faster.

The wrecks

Without a doubt, this coastline is a paradise for wreck divers. Just off Marseille, there are more than ten large vessels, including the Liban and airplanes from the Second World War such as the German JU-88 and a Messerschmitt 109. More can be found at the height of Toulon and around the islands of Hyerschen. Here too lie the famous Donor, the Grec and the Congerwrack of Port-Cros. Interesting stories are attributed to the Rubis submarine wreck in St Tropez, and the Togo. The majority of the wrecks were sunk by sea mines during the Second World War. Virtually all the wrecks on the Côte sit on sandy ground and have become artificial reefs, completely covered with fish and giant red gorgonians. The diving centers in these areas are specialized and well-equipped for wreck diving, so it is worthwhile to make use of their experience and services.

Donator wreck. The Donator, or Prosper Schiaffino as it was originally called, was built in Norway. She was 78.28m long and 11.94m wide with a draft of 5.54m. The ship was underway from Algeria to Nice with a cargo of wine, which was stored in countless barrels in the cargo hold and in large tanks on deck. By November 1945, the clearance of mines in the Mediterranean after the war ended was far from complete. Hence, the captain ordered increased vigilance and careful navigation. The freighter reached the Spanish coast without incident and carried on towards Toulon. Since the passage between the peninsula Giens and Porquerolles was blocked, the Donator had to pass on the south side of the island.

On 10 November 1945, the fully-loaded freighter was working against a strong wind known as the Mistral. At exactly one o’clock in the afternoon, disaster struck. A huge explosion rocked the ship and tore the bow apart. The ship had hit a sea mine, which was either set adrift or had gone unnoticed by the minesweepers. It took only a few seconds after the explosion for the hull to take in so much water that the stern of the Donator rose into the air. Although the ship fought to stay afloat—trembling and shaking but not capsizing—it ultimately succumbed and went under, with the bow going down first.

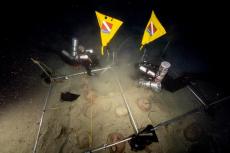

Diving: The wreck of the Donator now rests on a shallow sand bottom, with the blasted bow at 48m and the stern at 51m depth. The deck is at a depth of 40m, with the superstructures about 35m below the surface. The wreck is very large and swimming around it is only possible if the current is weak. A dive to the Donator is an unforgettable experience. More than 60 years on the seabed have transformed the ship into a thriving reef. Shoals of damselfish swim all over. In crevices and shelters, hundreds of orange red tilefish can be found.

(...)