Stretching over 500km, the Loyalty Islands of New Caledonia in Melanesia are a tropical oasis in the Pacific. It is here that one can experience the beautiful underwater world of Lifou, home to a diverse array of marine life. Pierre Constant shares his adventure there.

Contributed by

It was an early morning departure for the Betico 2, bound for Lifou Island. Check-in was at 6 a.m. at the ferry terminal in Noumea, the main port of New Caledonia. With the maximum luggage allowance at 15kg, plus a 6kg carry-on, I had to come one day early to bring my 42kg of excess luggage as cargo (comprising dive gear and underwater photography equipment). As a diver, there is no other option! Flying also limits you to 15kg max. Depending on sea conditions, the long ocean crossing to reach Lifou, in the Loyalty Islands, takes seven hours, as the ferry sails to Mare Island first. Finally, the Betico 2 docked at Wé, on the eastern coast of Lifou Island, shortly before 2 p.m.

After an initial visit in March 2022 (see issue #112), this was my second time in New Caledonia. Back then, I missed out on the Loyalty Islands, due to a lack of time. A tall and slim, long-haired Frenchman from Brittany, Pascal of Wé Plongée dive centre, was waiting for me. The transfer to his country home was in an old grey Dacia Logan car, with dents all over it, looking very local, indeed. In this remote land, most cars seem to have suffered some kind of damage. Lifou was to be my home for more than two weeks.

Located between 19°81’66” South Latitude 165°58’33” East Longitude (Astrolabe Reef) and 22°36’ S 168°57’ E (Walpole Island), the Loyalty Islands stretch over a distance of 500km from the northwest to the southeast. They are separated from the mainland by the Coral Sea, which is 100km wide and 2,000m deep. In order, from the southeast to the northwest, are the Walpole Islands, Mare (820 sq m and 130m high), Lifou (1,115 sq km), Ouvéa (160 sq km), Beautemps-Beaupré Island and Astrolabe Reef, which is underwater.

Geology

The Loyalty Islands are an ancient intra-oceanic volcanic arc of the Eocene age, resulting from the subduction of the Australian Plate under the Pacific Plate. It became a hot spot during the Oligocene and Pliocene periods. The construction of the atolls, between the Pliocene and the Pleistocene, was made at various times by repetitive subsidence.

Ultimately, the collision of the Loyalty Ridge with the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) arc during the Pleistocene created a tectonic uplift with the emergence of the atolls. This was due to the convex rise of the oceanic crust of the Australian Plate.

Twenty-five million years ago, Lifou was a volcanic island with a fringing reef. Five million years ago, despite new eruptions, the volcano was eroded. Three hundred thousand years ago, the sea level was 120m above actual level and the atoll had an inner lagoon. Then the ocean receded. The Riss-Würm ice age 15,000 years ago, with the sea level 100m below, saw the formation of caves and underground rivers. Most of these are flooded today, but still active.

Made of compact limestone, the barrier reef is 3km offshore. The centre of the island is flat, and the old lagoon is filled up with crystallised limestone, sand and conglomerates. In the north, the plateau is 25m high and the reef crown rises up to 90m. In the south, the plateau is 40m high and the crown rises up to 110m. The limestone formations have a “dip” of 5 to 10 degrees to the northwest. The Loyalty Islands are consequently tilted.

The biggest and oldest caves in Lifou—Hnanawei, Wanaham and Inegoj—would have been formed between 190,000 to 130,000 years ago. The most intense karstification occurred during the Riss-Würm glaciations 100,000 to 150,000 years ago. No surface rivers exist, as everything flows underground. Since heavy rains take place in February to March, during the rainy season, part of the rainfall gets stocked in the underground nappe.

History

As for the human history, Austronesians came to Melanesia in 3000 BC, from Southeast Asia. The first migration of humans from north Melanesia (Admiralty Island) to New Caledonia took place ca. 1700 BC. Lapita pottery found in Koné (on New Caledonia’s western coast) was dated to 1400 BC.

From the 16th to early 19th century, Tongan and Samoan migrations to Lifou occurred, possibly from Vanuatu too. If Captain James Cook discovered New Caledonia on 4 September 1774, it was only in the late 18th century that two British ships landed at Lifou Island. The Loyalty Islands were named after one of the ships. In 1829, French navigator and explorer Dumont d’Urville rediscovered the Loyalty Islands and drew a definitive marine chart. Whalers had already been visiting the place since 1810.

Dive operator

Based at Wé marina (near the port where the Betico 2 arrived), Wé Plongée has been in operation since 2018. Its founder, Pascal, set up the dive centre in a container, which also acted as a bakery since he was baking bread every day!

He is a French FFESSM instructor, as well as PADI and SSI instructor, and he conducts “baptêmes” (i.e. Discover Scuba) experiences for beginners, and also dive training at different levels. An inflatable zodiac is used for outings in Chateaubriand Bay. Most of the dive sites are conveniently five minutes away. Permission to dive a specific area is granted by the tribal custom authorities, a must for any activity in Lifou. The area outside the bay is reserved for traditional clans. Certified divers go for two dives in the morning, while Discover Scuba and dive training takes place in the afternoon.

Dive sites

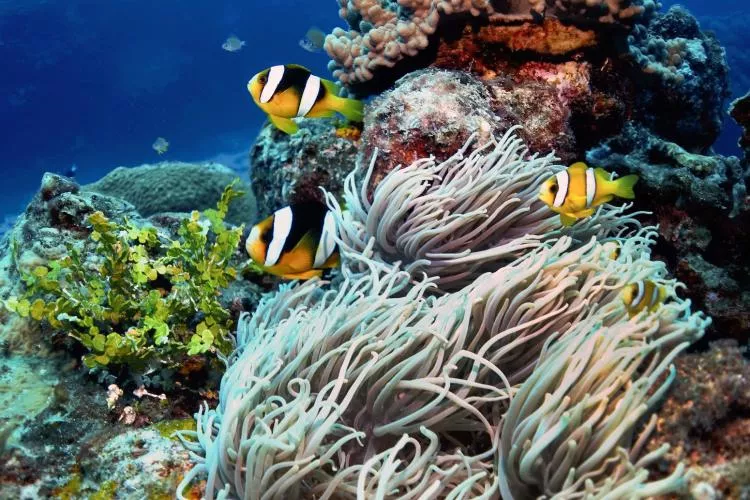

Province Good and Canyons. On the first day, the plan was visiting Province Good and Canyons—pretty similar dive sites. The reef was massive, cut with numerous canyons, swim-throughs and tunnels, with white sandy patches around them. It was an atmospheric experience, since the fish life was so inconspicuous, i.e. there were no “big” things, no large schools of fish, and only the usual small reef fish such as butterflyfish, parrotfish, surgeonfish, the occasional angelfish, as well as the odd school of goldspot seabream (Gnathodentex aureolineatus). Colonies of orange-fin anemonefish (Amphiprion chrysopterus) with a white tail fin were rather common—as were Clark’s anemonefish (A. clarkii). The blackfin hogfish (Bodianus loxozonus) was a frequent sight. The pineapple sea cucumber (Thelenota ananas) and giant clams (Tridacna squamosa) were seen on the sandy bottom as well.

Tombant de la Marina. On day two, Pascal took me to one of his favourite sites, popular with beginners for being a training site. Tombant de la Marina was a small drop-off, with a maximum depth of 13m, onto white sand and scattered coral bommies. Marine life tended to be more conspicuous and included green sea turtles, whitetip reef sharks, Napoleon wrasse, bluefin jacks, coral grouper (Cephalopholis miniata), peacock grouper (Cephalopholis argus), porcupinefish and guineafowl puffer. I came across a number of red and black anemonefish (Amphiprion melanopus), the devil scorpionfish (Scorpaenopsis diabolus) with yellow and red pectoral fins, the oval-spot butterflyfish (Chaetodon speculum), the yellow bar or yellowband parrotfish (Scarus schelgeli) and the lemonpeel angelfish (Centropyge flavissimus), which was yellow with a blue ring around its eye. “The other day, during training, we saw a manta ray and even a hammerhead shark once,” said Pascal enthusiastically.

Patates de Hnassé turned out to be rather pleasant. It was a collection of large coral bommies scattered over sandy flats, with an outer slope open to the blue. Among other species, there was the teardrop butterflyfish (Chaetodon unimaculatus), Papuan scorpionfish (Scorpaenopsis papuensis), chevron butterflyfish (Chaetodon trifascialis) and bluedash butterflyfish (Chaetodon plebeius). Twin-spot or spotted garden eels (Heteroconger hassi) adorned the sandy bottom in places. Of the grouper family, several were present, including the honeycomb grouper (Epinephelus merra), the blacktip grouper (Epinephelus marginalis), which was red with white blotches, and the lunar tail cod or lyretail grouper (Variola louti). A wide patch of Alveopora coral, with little daisy-like polyps, was worth a look. Blue-spotted stingrays (Neotrygon kuhlii), clown triggerfish and the sling-jaw wrasse (Epibulus insidiator) appeared once in a while.

Bouée Verte was near the entrance channel, between red and green buoys. There were four aligned bommies, with a deep slope to the left, descending to 25m and beyond. Both green and hawksbill sea turtles were seen, as well as whitemouth morays (Gymnothorax meleagris), which were pale brown with white dots, semicircle angelfish (Pomacanthus semicirculatus) and bigeyes (Priacanthus hamrur), which were crimson red in colour and had black eyes. The Egyptian seastar (Gomophia egyptiaca) caught my eye here.

Caves

Taking advantage of a day off, I decided to tour the northern end of Lifou and hired a car to do so, as visiting the whole island was an absolute must for me. The tar road first led me to Hnathalo. From then on, the road to Tingeting became quite challenging. It seemed to me that a pastime of some of the Kanak youth was to destroy the existing signboards—whenever there was one, that is! So, I found myself asking for directions all the time.

La Grotte du Diable. Finally, I found La Grotte du Diable (Devil’s cave). The landowners, an elderly couple, asked for an entry fee of XPF2,000. A 10-minute trail through the forest led to the base of a cliff, the outer limestone crown of the atoll. After a bit of a climb up and down, I found myself in a heavily fractured cave with an open roof. A bunch of human bones lay in a cavity on the left, and a couple of human skulls grinned stoically on a rock shelf above. These were remains from cannibal times and macabre rituals, I was told.

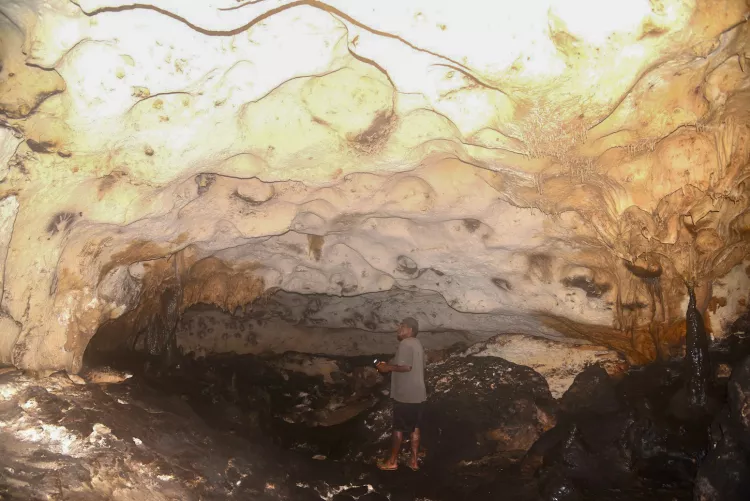

The number of caves in Lifou was impressive, some reaching over a kilometre in length, with the longest up to 8km. Having read about the presence of water in some of these caves, I decided to give diving in Grotte de Luengoni (Luengoni Cave) a try, which was located on the southeastern coast.

Grotte de Luengoni. As was appropriate, permission needed to be requested from the landowner. The athletic-looking, self-proclaimed Kanak independentist Pascal Qazing ran tours to the cave and agreed to take me along one morning. For the benefit of tourists, Pascal had lit small candles inside the cave and partly around the inner lake where day visitors could delight themselves with a dip in the cool waters.

With tank on my back, I submerged into the apparently clear pool. The water temperature was 21°C. I followed a narrow tunnel up and down, with some stalactites and stalagmites—nothing really fancy, until I reached the halocline at a depth of 10m. Then, my camera’s dome lens suddenly got foggy, which was condensation due to the higher temperature of the saltwater. So, I could no longer take photos. Annoyed, I turned around, with a gnawing dread that I may have flooded my camera.

Inegoj Cave. When inquiring about Inegoj Cave, I found the landowner sitting behind his table listening to the radio. The 78-year-old Cefo referred me to a man managing the area in town. I succeeded in getting an authorisation to visit the cave in a couple of days. Unfortunately, it would turn into a “no go,” because the only guide to the cave was working in the yam fields and was not available! In Inegoj Cave, a 500m-long tunnel led to an underground lake that could have been promising, but hard to get to.

More diving

Following Pascal’s recommendation, I made contact with a dive centre located in Easo, on the northwestern coast of Lifou. Run by friendly Bastien, a tough-looking bald-headed fellow, Lagoon Safaris had been in operation since 2013. The 7.5m fiberglass boat with a 175 HP outboard motor had room for eight divers. “We have about 25 dive sites to the north of Baie de Jinek, towards Cap Martin,” said Bastien.

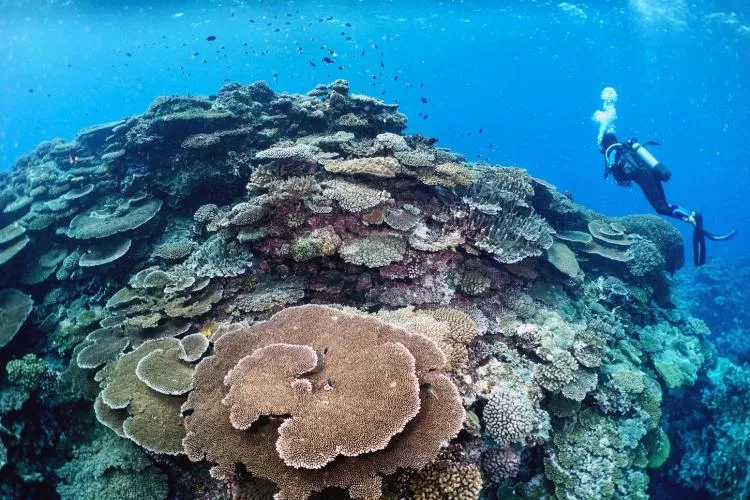

Gorgones Reef. The diving here was strikingly different to that of the confined waters of Baie de Chateaubriand. Cobalt blue waters, gin-clear visibility and plenty of fish welcomed me at Gorgones Reef. Open to the ocean and bathed with a regular south-to-north-flowing current, the site appeared to be very alive and exciting. Add to that a bonanza of gorgonians and soft corals, the health of the reef was vibrant. Two pinnacles rose from a depth of 30m-plus, on white sand. The water temperature was 27,5°C.

Bluefin jack paired with barcheek trevally or jack (Carangoides plagiotaenia), which were distinguished by the chevrons on their silver sides as well as a black dash on the gill cover. Red snapper (Lutjanus bohar) mixed with a large school of black snapper (Macolor niger), revolving close to the surface between the pinnacles. Some large dogtooth tunas (Gymnosarda unicolor) cruised by in the deep. The occasional whitetip sharks were spotted resting on the sandy floor. On the top of the pinnacle, I approached very closely to some sling-jaw wrasse (Epibulus insidiator), in both yellow phase and brown phase.

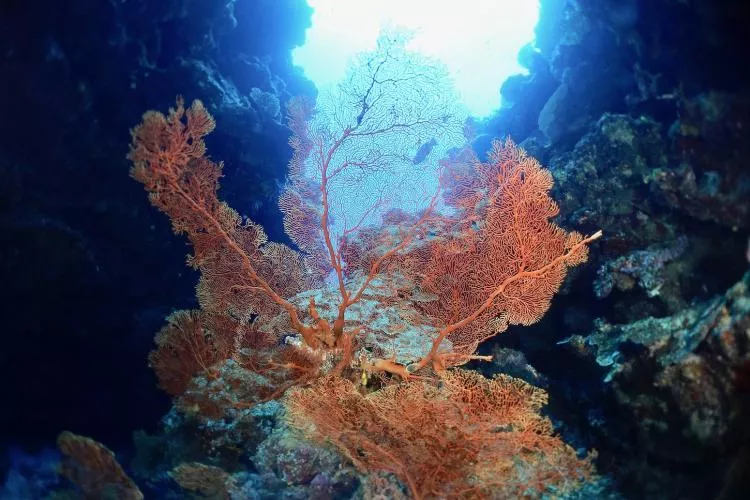

L’Arche. A stone’s throw away, L’Arche was a gigantic archway decorated with enchanting red and gold gorgonians. Towards the top of the mound, three snubnose pompanos (Trachinotus blochii), which were silver with yellow fins, teamed up with a school of bigeye jacks, which were rather shy. A yelloweye leatherjacket or whitespotted filefish (Cantherhines dumerilii) showed up inquisitively. Peacock grouper (Cephalopholis argus) and coral grouper (Cephalopholis miniata) roamed everywhere. A camouflage grouper (Epinephelus polyphekadion) hid under an overhang, gazing at me placidly. A 2m-long grey reef shark swam leisurely by, at depth. Snubnose or bignose unicornfish (Naso vlamingii) were a visual delight, with their blue filaments streaming behind them, off their tail fins.

Cap Martin, farther north, offered the attraction of a big coral bommie a short distance away from its wall. The spot was full of gorgonians and soft corals. As I explored a smaller bommie in the protection of the strong current, Bastien frantically pointed out something behind me. I turned around just in time to gaze in amazement at a beige-to-light-brown hammerhead shark curving gracefully around behind me. It was such a surprise that I did not even have time to take a photo!

Tomoko. At Tomoko, the coastline was carved with sea caves. One of the tunnels was a true lobster lair of the pronghorn spiny lobster (Panulirus penicillatus).

Night dive. Bastien convinced me to join him for a night dive. “A good chance to meet the nautilus!” he exclaimed, smiling. The offer was too tempting to refuse. Starting from the beach in Easo after dark, we swam with snorkels for about 10 minutes, before we submerged. Soon, I was in sight of a festival of basket stars (Astroboa nuda), fully deployed in a feeding position.

Bastien found a black Hancock’s flatworm (Pseudobiceros hancockanus) with an orange and white girdle. I marvelled at a pink velutinid (Coriocella sp.) with black lines, which I had never seen before—neither in any book, nor on the internet; I suspected it was a new species. An orange-spotted common box crab (Calappa lophos) posed on a rock. A yellow-margin moray (Gymnothorax flavimarginatus) was on display under a staghorn coral. To add a little spice, a large-banded sea krait (Laticauda saintgironsi) foraged in the open, above the sandy flats, oblivious of my presence.

Labyrinthe. Before my departure, Pascal insisted on taking me to the Labyrinthe, one of his favourite sites. It was a true maze of canyons, swim-throughs and tunnels, where one had to squeeze through like a rat. This was my chance to meet the elusive, colourful harlequin tuskfish (Choerodon fasciatus), which was red with white and grey bands, hiding in the darkness.

Onward

A loop road went around the northern end of the island to Hnathalo, Wanaham Airport, Jokin and Xepenehe. Another loop skirted around the coasts along the west (Drehu), south (Mu) and east (Traput) of Lifou.

Lifou offered plenty of possible excursions and guided hikes, to either caves or scenic viewpoints, such as the Jokin Cliffs or Marmites du Cap des Pins, where huge tidepools are found on elevated reef terraces. It was an invitation to take a bath with a view.

Should you fancy idyllic beaches, you had the choice between Chateaubriand Beach, Luengoni Beach or Peng Beach. Beyond a green patch of indigenous forest, the secluded Kiki Beach was a jewel for nature lovers, located at the base of a line of cliffs, south of Xepenehe. North of Easo, the Baie de Jinek had an attractive underwater trail for snorkellers, who may swim on their own. Little buoys with flags marked the way on the surface.

For the optimal diving experience, I would recommend one week on Lifou, shared between Wé Plongée on the eastern coast first, followed by Lagoon Safaris, on the northwestern coast. Only then may you fancy other Loyalty Islands, such as Maré or Ouvéa,—if you have time, of course.

Fetra He

A 6 a.m. appointment with Haman brought me to a hidden place behind Wanaham Airport, on my last day. My intention was to visit the little-known cave of Fetra He. “I am not working the yam fields on Sunday; it is the day of the Lord,” confided Haman. We sat and chatted for a while in his garden, as the custom required, so he knew about my purpose.

We entered the forest behind his house. Hidden in the vegetation, the small porch of a cave appeared. We had to squat to go in. Cave swiftlets flew about, bumping randomly into my face. “Here is the guardian of the cave,” he whispered, pointing to the right. My eyes fell upon a skull in a hole. We ended up crawling on all fours—as I wore my headlamp—to penetrate tight and dark passages soiled with bat guano. Some crushed human bones lay about. After a hundred metres of dirty progression, my hands and knees were sooty black.

We reached a spacious chamber with dark stalagmites and stalactites. To my absolute bewilderment, the walls were covered with stencils of hands in black, sometimes red. “Archaeologists came here over 30 years ago and dated these with Carbon-14,” said Haman. “They are 3,000 years old and belong to the Lapita people.”

These early navigators from Southeast Asia left traces of their migration with renowned pottery, all across the Pacific. Lifou’s ancestors had come from northern Melanesia, from the Admiralty Islands where I had lived before, in Papua New Guinea. Everything fell into place. Somehow, my feeling was that I had been on the path of the Lapita people for a number of years—as if, in a former life, I had been one of them. Beyond the screen of certitudes, life works in mysterious ways… ■

Thanks go to Pascal of Wé Plongée, Wé marina, Lifou (lifouplongee.com); Bastien of Lagoon Safaris, Easo (lagoon-safaris.nc); and Pascal Qazing of Les Joyaux de Luengoni (Luengoni cave) at Facebook @Pascal Neyhrtg or email mariapoedi@gmail.com or elkyhrtg@gmail.com.