Have cownose rays sniffed out a new home in Bermuda?

The whitespotted eagle ray has been the only inshore stingray species in Bermuda for hundreds of years.

Not anymore, according to a study.

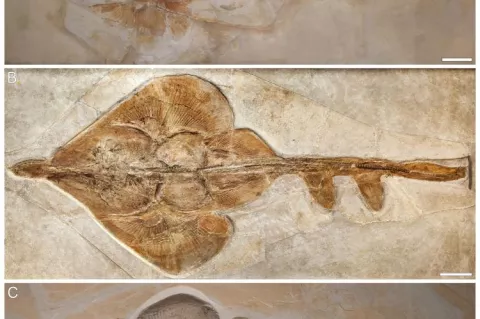

The presence of the Atlantic cownose ray in the area has been confirmed, 1,000km away from where they are normally found, along the continental shelf of the Atlantic US coast.