How did a late 19th-century ship from the Great Lakes region of the United States end up shipwrecked off the coast of France, in the Bay of Biscay? Pascal Henaff has the story and shares impressions from a dive on the wreck.

Contributed by

Factfile

WRECK LOCATION

46° 32’ 274 North – 02° 16’ 583 West

20.3 nm northwest off

Les Sables d’Olonne

Bay of Biscaye, France

Atlantic Ocean

Depth: 48m

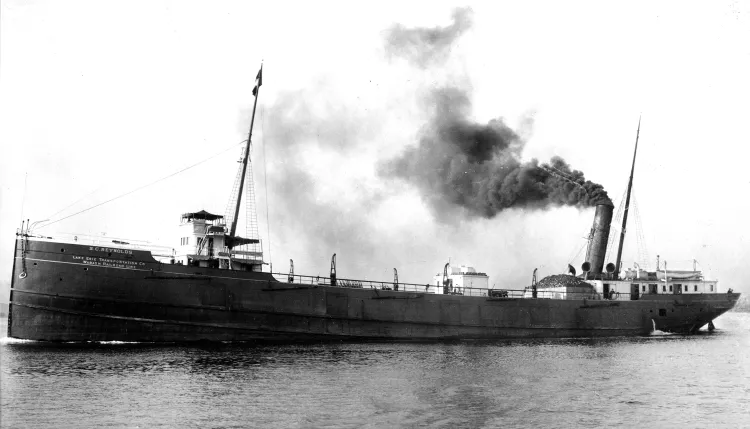

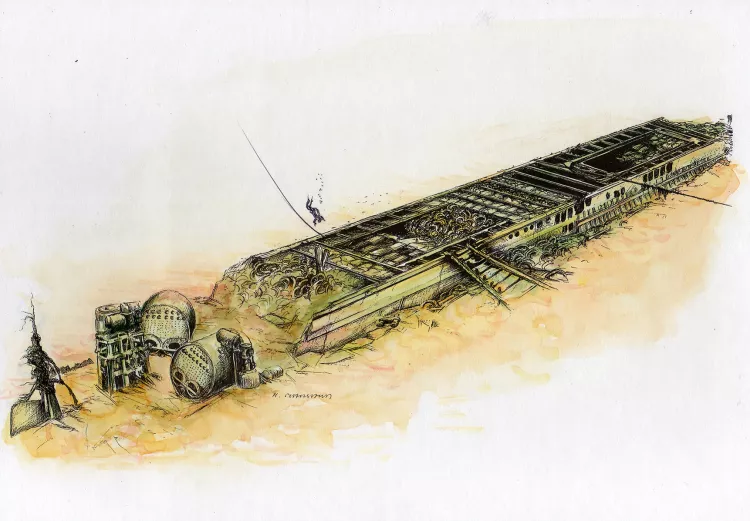

The John G. McCullough was built in 1890 by the Union Dry Dock Company in Buffalo, New York, USA, on behalf of the Erie Railroad Lake Line company. At 1985 gross tons, the ship measured 77.72m long and 12.22m wide. Two boilers fed a triple expansion machine, located at the rear of the boat. The remaining space on the ship was used for freight.

Launched under the name of S.C. Reynolds, it was renamed John Griffith McCullough in 1902 in honour of the company’s president. McCullough was born on 16 September 1835 in Newark. After graduating from the University of Delaware in 1855, he worked as a lawyer in Pennsylvania, California and Vermont. He eventually settled in New York, to chair the steering committee of the Erie Railroad Company in 1888, and then became governor of Vermont in 1902. He died in May 1915.

History

In the beginning, the John G. McCullough performed its function on the Great Lakes (a historical photo shows it sailing down the St. Clair River). Then in 1915, it was sent back to the shipbuilding company in Buffalo, and on to Davie Shipbuilding, a shipbuilding and repairing company in Quebec. The vessel had to be modified for another use, different from the one it had had on the Great Lakes. During this same time, the United States went to war, just after the Lusitania was torpedoed. The John G. McCullough was then requisitioned by the US Army Transport Service (ATS).

In early May 1915, the vessel was under the command of Frederick Hastswell. It left London filled with ballast and sailed to Belgium. There, it picked up freight (truck axles and wheels, cement bags, etc) for the US Army. It then headed towards Rochefort, armed with a 90mm gun. The vessel had a total crew of 32, including four Americans, 26 Brits, one Dane, and one German. The US Army Brittany Patrol Division instructed the ship to navigate around the Raz de Sein, and travel down the coast along the Glénan Archipelago (Archipel des Glénans) and to the island of Groix (Île-de-Groix). The ship then had to sail away from the Quiberon Peninsula in order to later reach an escort vessel, which was bound for the island of Aix (Île-d’Aix).

In 18 May 1918 at 4:45 a.m., the ship was situated to the south of the island of Yeu (Île d’Yeu); visibility was between one and two miles. Without zigzagging, the ship headed south-east, at a speed of 6.5 knots. The American patrol boat Emiline, which was escorting the J.G. McCullough to port, was one mile behind it. Navigation lights on the ship had been turned off, and all other lights had been obscured.

Suddenly, a violent explosion took place on the starboard side, 10m aft of the bow, which surprised everyone. The officer in charge of the watch, and the helmsman, said they saw the wake of a torpedo, but no one had spotted a submarine periscope. No distress message could be sent because electrical power was out in the ship’s dynamo room.

The J.G. McCullough started to sink bow first. Badly partitioned, the ship went down in three minutes. The crew just managed to take shelter inside two lifeboats, which had been hastily dropped into the water. Meanwhile the escort patrol boat launched five depth charges but to no avail. Then it went to assist those stranded. The escort patrol boat brought the shipwrecked sailors back to the harbour of La Pallice.

Only one crew member was lost: second engineer and officer, Daughtry, who had returned to the boiler room after the explosion in order to try to restart the engine.

The report at the time raised doubts as to whether the explosion had been caused by a mine or a torpedo. From the German side, it was thought that the shipwreck must have been the work of UB 74.

UB 74 was a submarine of the UB III type (coastal torpedo attack boat class). It was 55.30m long and armed with 10 torpedoes and one 88mm canon. UB 74 had a crew of 34 and could dive to a depth of 75m. On the day of the alleged attack of the J.G. McCullough, UB 74 was commanded by Ernst Steindorff. It was eventually sunk by the patrol boat Lorna in the South of England (Lyme Bay) on 26 May 1918, using depth charges.

Diving the wreck

The J.G. McCullough lies in quite good shape at a depth of 48m, in particularly clear water, 20nm off Les Sables d’Olonne. A telephone cable, which started at the coastal town of St Hilaire de Riez (formerly linking the old world to the new, which is now out of service), runs across the wreck.

Thanks to its cargo of cement bags, which preserved the original shape of the wreck, except for the damage suffered at the bow due to the explosion, the remaining three quarters or so of the ship have been kept as they were on the day the vessel sank.

In summertime, a thick blanket of plankton develops in the 10m zone. What light penetrates through the depths to the wreck is enough to illuminate almost the whole ship, at a glance. Horizontal visibility often reaches 20m. The hull rises to the height of four or five metres above the sea bottom.

On the starboard side, part of a cargo boom rests on the sand. It is possible to slip under the deck beams—in particular, at the front end of the port side—in order to swim one’s way closer to the cargo and meet today’s “crew members,” mainly consisting of lobsters. On the starboard side, a large flap of metal sheet rests against the hull. Lots of harmless conger eels gather under it and hardly give way to our passage. On the port side, some pieces of the fittings that slipped out of the ship, can easily be recognised.

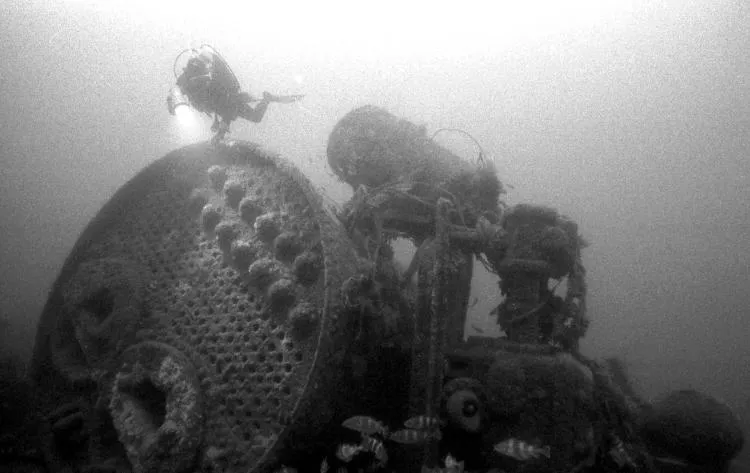

The most interesting part of the wreck is in the aft area. Here, two wonderful boilers are slightly displaced, and the imposing machine towering above this part of the wreck is colonised with sea anemones. The frame of the stern still holds the rudder, but the propeller is half buried in the sand. A fishing net is tangled around the rudder stock, giving it a ghostly aspect.

It is an easy dive despite its depth. This compact wreck is easily navigated. Moreover, it is the only wreck in this area that is typical of the Great Lakes of North America (the engine and both boilers are located in the aft end). ■

To learn more, see the video by Pascal Henaff about the Bay of Biscaye’s wrecks off Les Sables d’Olonne at: youtube.com/channel/UCnCdlg34vdGSqIGv4E1dq7A