I first learned about this unusual lake, nestled in Marble Canyon Provincial Park of British Columbia (BC), Canada, when some friends living in Kamloops asked me to join them for a dive at a local, clear freshwater lake. Since it was only a few hours from Vancouver, I decided to take them up on their offer and headed for the interior parts of BC.

Contributed by

I have always wanted to explore this area and was thrilled even more when they told me of the strange coral-type of life living in the lake. Intrigued, I invited a few more friends to join the excursion: my husband and dive buddy, Wayne Grant and Ron Akeson, a marine biologist from Bellingham, Washington, USA. Wayne would record the data, I would document with underwater stills and Ron would video the dive with his HD video camera.

We arrived at a part of the lake used by local divers and assembled our gear. The lake is 4 miles (5.7 kilometers) long and 0.5 miles (0.8 kilometers) wide at an approximate altitude of 2,690 feet (820 meters), with a maximum-recorded depth of 65 meters. Travis Van-mole, who I originally met through Ron, was our host and would also be our underwater guide.

“We dive here all the time,” said Travis while assembling dive gear. “The ice diving is great here, as well as several other lakes in the area. We have a lake with caves and even know of several more that have the cold-water corals.” According to Ron, the ‘cold-water corals’ are actually called microbialites, a bacterial type of life that builds a hard carbonate shell or casing. These formations are believed to have begun forming over 10,000 years ago after the retreat of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet.

“There is also a research group of scientists and astronauts from both NASA and the Canadian Space Agency studying the microbialites at the other end of the lake.” Travis added. The water was cool and very clear with a fine silt mixture of substrate. Visibility underwater was an impressive 80 feet (24 meters) and the water temperature was in the low 40’s F (4.4°C). Not many fish were found, but plenty of vegetation grew abundant in the shallow depths.

Strange shapes

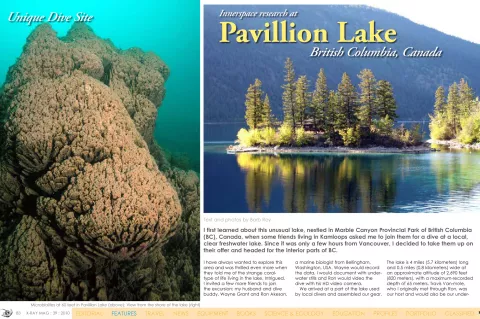

Travis led us down to 60 feet (18 meters) where we saw the first signs of microbialites. These mounds were tall and cone-like in shape, resembling huge termite mounds found on land. They varied from 5-9 feet (1.5-2.7m) in height and 3-4 feet in width at the base, tapering off into peaks at the top, using the rocky slope to build upon. It looked as if the structures were crafted from mud. No visible life was noticed, which none would be expected if made from a bacterial compound. Travis took us to 80 feet (24 meters) where we found an open area full of more microbialites structures, but much smaller, only a few feet in height. In another section there was another batch of different shaped structures of similar size and appearance.

Our dive took us around a small island near the entry area, and throughout the dive, the microbialites formations were found in patches, where the formations were all very close in appearance. On the second dive I used a 50mm macro lens on the camera for a closer look at the microbialites. This proved to be quite interesting, especially when we later studied the video and examined my images on a big screen monitor. The subjects were an aqua green and pink in color and seemed to be very much alive and thriving in Pavilion Lake. In fact, small mud-like formations were growing on logs, boulders and covering fallen trees underwater.

Second time around

During a later trip in the Spring of 2010 when the three of us took this magazine’s editor, Peter Symes, up for a dive in Pavilion Lake, I looked around at the steep rocky cliffs surrounding the lake. Remembering Ron had mentioned a receding glacier, the tall rocky structures on the hillside began to make sense, and it was easy to correlate how they resembled the tall underwater structures. Peter was equally as fascinated with the microbialite formations as we were. During the dive when we were at the tall structures, one of the mounds had toppled at the top portion, revealing a honeycomb interior.

Third time’s the charm

During another return trip later in the summer, Ron Akeson and I visited the Pavilion Lake Research Project headquarters where scientists and various experts are trying to learn more about the microbialites and what makes this lake such an unusual environment to host the microbialites in.

According to Dr Allyson Brady, principal investigator for the research project specializing in isotope geochemistry, the microbialites are believed to be formed from biological activity representing some of the earliest remnants of life on Earth—2.5 billion to 540 million years ago. Experts in photosynthesis, robotics, environmental fluid mechanics, planetary science, geology and a myriad of other fields of study have gathered from around the world to work together to collect data and utilize their joint resources.

One of the things the Pavilion Lake Research team is looking for is bio-signatures that will help explain what ancient microbialites were like and compare them to modern day bio-signatures. Scientists and astrobiologists can then apply the context information to their studies of the solar system and learn more about the geologic record of the area. “At Pavilion Lake we are working in an actual hostile environment,” said Brady. “Since we are underwater, we’re faced with similar challenges as space scientists would be, such as limited communications, being on life support and having things break down. By experiencing these problems firsthand in a field setting, it gives scientists an idea of what might happen during space exploration and solutions to possible problems,” she said.

Donnie Reid, a fellow diver and underwater photographer, is the project’s logistics and operations manager.“By 2050, humans are expected to be on Mars. To get there, however, it will take nine months and nine months to return. Because Mars and Earth share a similar geological history, Mars may also have microbialites. “To work in this semi-controlled environment has given us the opportunity to estimate what we might find or experience and how to deal with it,” said Reid.

We were also able to meet and talk with Chris Hadfield, an astronaut for the Canadian Space Agency and scheduled to command the Space Station in 2012. Hadfield was prepping for a sub run with Bernard Laval, a physical limnologist from the University of British Columbia. These analog missions range in duration from 1-2 hours long, depending on the series of test or samples required. The submersibles used by the team are from Nuytco Research in North Vancouver, called “Deep Worker”. These one-pilot subs provide eight hours of power and eight hours of life support.

AUV’s (Autonomous Underwater Vehicles) and ROV’s (Remotely Operated Vehicles) are also used as satellite-analogues. They are able to take measurements, provide sonar data, photograph large areas and are used for remote sensing and monitoring. Currently, the research team is looking into other lakes in the area for 2011. For more information on microbialites and the Pavilion Lake Research Project, check out their website at: www.PavilionLake.com.

Visiting BC

Any trip to British Columbia’s interior or coastal destination will provide visitors an unforgettable adventure any time of the year. The people are friendly, and humor abounds. The underwater life, no mater where you go, can be as interesting as the breathtaking scenery above water. When planning a trip to BC, you might want to look into the following websites for more information:

• www.HelloBC.com

• www.DiveIndustryBC.com

• www.BCFerries.com ■