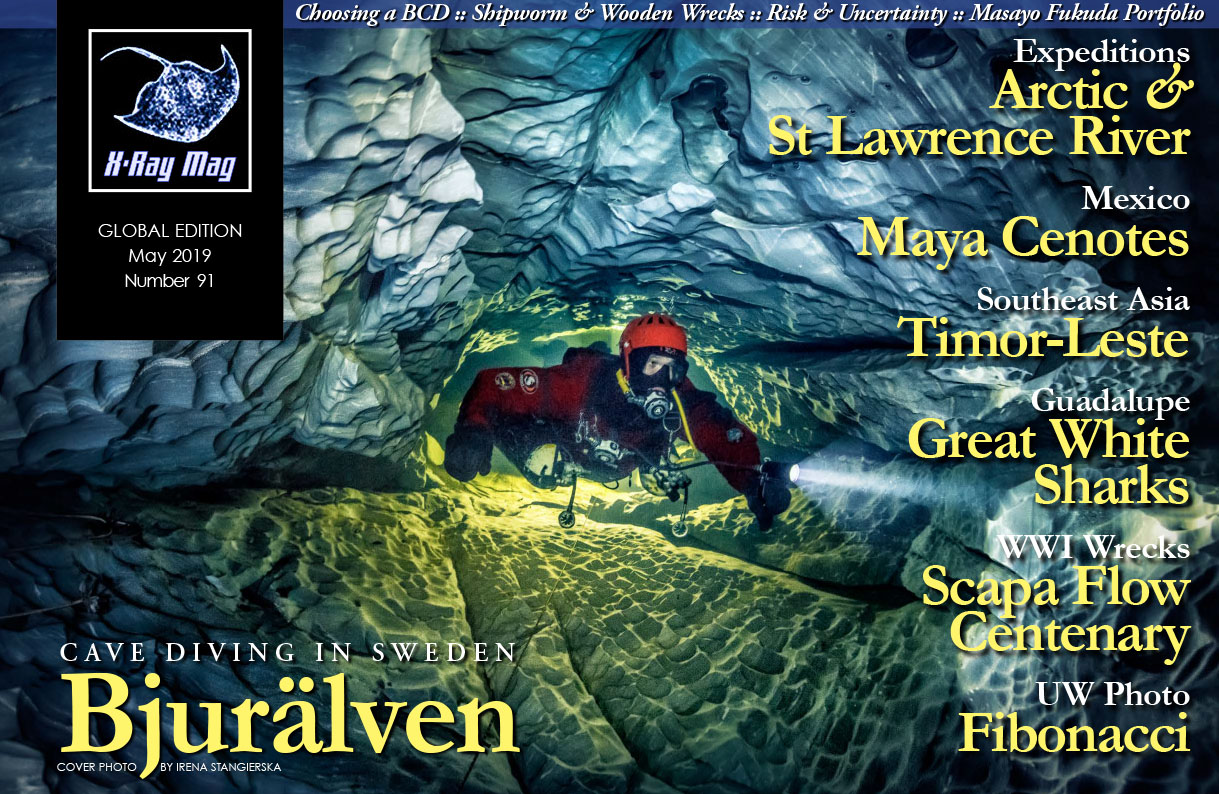

“You’re crazy; I don’t get in the water with bitey things!” The announcement of my impending great white shark trip drew a variety of such responses from horrified friends. The undisputed bad boys of the shark world, great whites are the largest of all predatory sharks, reaching lengths of up to 6m and weighing in at over 2,000kg. The concept of seeing them up close, even from within a cage, invoked a variety of additional gems including “Oh my God,” “I hope you come back with all your limbs” and “Come back alive.”

Contributed by

Factfile

GREAT WHITE SHARK MIGRATION

Great white sharks spend autumn and winter at Guadalupe Island before journeying to an isolated stretch of the Pacific Ocean between Baja California and Hawaii dubbed the "White Shark Café." Beginning in late winter, this pilgrimage has long baffled scientists, not just because it takes the sharks a month to get there, but the area does not seem to possess food to support their diets.

Scientists have recently discovered the area to be teeming with squid and small fish in "mid-water," a deep-water expanse positioned just above the deepest areas of the sea where there is complete darkness. Here, the sharks engage in “bounce dives” down to 1,400ft during the day, and 650ft at night to feed. ■

The blatant sensationalism of the Discovery Channel's "Shark Week" notwithstanding, the movie Jaws has not done the image of sharks, and great whites in particular, any favours. Unfortunately, perception overrides facts. “Sharks are dangerous and eat people,” say those who know better.

Certainly, there have been attacks and people have died or been seriously injured, but a healthy dose of perspective is required. One is more likely to get struck by lightning or win a lottery (or both) than be attacked by a shark. My phobic friend has never even seen a shark outside of the Toronto’s aquarium, yet will not even go into the ocean. Surely, a movie from more than 40 years ago cannot prompt such irrationality, can it? Apparently, it can.

Although many shark attacks can be attributed to great whites, new research has revealed them to be naturally curious, "test biting" their potential prey before releasing it. Many attacks are not fatal, indicating humans are not a preferred menu item. Unfortunately, the naysayers’ minds are already made up. In fact, a recent scientific study revealed that selfies kill 20 times more people than sharks!

I previously had the opportunity to see great whites off Cape Town in South Africa. Although shark numbers were high, low visibility combined with a shark cage as long as my sofa and no air supply made photography difficult. Despite this, observing these magnificent creatures in the wild was extraordinary. There was no fear, only exhilaration; I could not wait for another opportunity. Five years later, that chance arose at Mexico’s Guadalupe Island.

Guadalupe Island

Situated in the Pacific, 240km off Mexico’s Baja California peninsula, Guadalupe is one of the world’s premier locations for observing great white sharks. Volcanic in origin, the island measures 35km long and 5.9km across. A chain of high, volcanic ridges ascends to 1,298m at its northern end and 975m at the southern end. The southern part of the island is barren, although pine forests are found in the interior.

Although located in a biosphere reserve, approximately 200 people reside on the island, most of them abalone and lobster fishers. Ironically, they had no idea about the sharks, as humans and sharks reside along opposite sides. A Mexican naval base is also found on the island.

The island is also home to three pinniped species: California fur seals, California sea lions and northern elephant seals. Ruthlessly hunted, the northern elephant seal was believed extinct in 1884 until a remnant population of eight individuals was discovered on Guadalupe in 1892. Granted protection by the Mexican government in 1922, the species has made a remarkable recovery. Today, the population has recovered to over 100,000, ranging from Mexico to Alaska.

It is this abundance of food that lures the sharks in such large numbers. Unlike in South Africa, Guadalupe’s visibility is crystal-clear, sometimes in excess of 30m. Although the sharks are present most of the year, the prime viewing season is between August and November, when sea conditions are calmest.

Getting there

According to Ralph Waldo Emerson, “It’s not the destination, it's the journey”—an adage that proved especially true when travelling to Guadalupe. From my home in Toronto, it was an easy five-hour flight to San Diego, where I stayed a night at the Hampton Inn, the tour departure point. A beautiful city with a laid-back vibe, San Diego quickly won me over, and I had a pleasant afternoon exploring the area.

The following morning, everyone assembled in the lobby prior to the 10:30 a.m. departure. The group consisted of 15 people (14 men and one woman) from Germany, France, United Kingdom, United States and Canada. Unsurprisingly, there was a lot of luggage—a good deal of which I suspected was camera-related.

From the hotel, a chartered bus took us to the departure point in Ensenada, a 90-minute drive south of the border. Although the border at Tijuana was a mere 20-minute drive away, I surmised crossing it would take a LOT longer. The world’s busiest land border crossing, fifty thousand people pass through daily and I expected nothing short of pandemonium.

Once there, everyone had to disembark, taking all their luggage with them. A short walk led to immigration, where an official greeted me with a cheerful “Hola” and a smile. As the company had filled out all entry paperwork in advance, I presented my arrival card, she stamped it and I was in Mexico. I have had more difficulty entering my own country!

Back on the bus, it was a scenic 90-minute drive down the coast to the town of Ensenada. Enroute, we stopped at a 7-Eleven for some snacks. Upon perusing the bakery’s diabetes-inducing pastries, I opted for a coffee with canella (cinnamon), a combination I immediately savoured.

Farther along, the drive was quite scenic, the rugged coastline interspersed with swanky expat homes and the occasional resort town. The sight of high-rise condos along the barren coast was decidedly incongruous. While not the palm-fringed shores of tourist brochures, the pristine beaches stretched for untold kilometres.

Passing by the Fox Baja studios, I just managed a glimpse of the massive water tank used during the filming of James Cameron’s film Titanic. Further south, we stopped at a scenic viewpoint. The coastline’s rugged arc faded into the midday haze, as fish pens stocked with tuna for the Chinese market punctuated the cobalt ocean.

We soon arrived in Ensenada, a bustling port city that is the third-largest in Baja California. An important commercial, fishing, and tourist port, its extensive marina harbored a wide variety of vessels from small fishing boats to a monster cruise liner. Also waiting was the MV Solmar V, our home for the next five days.

The liveaboard

A member of the Pelagic Fleet, the Solmar V is a 34m long exploration vessel that is one of the pioneers of Guadalupe cage diving. Ornamented with mahogany, brass and granite table tops, the carpeted salon featured a large-screen HDTV with VCR, DVD player and stereo system. Lunch was waiting in the saloon and everyone quickly tucked into a sumptuous spread of shrimp, salsa, guacamole and tortillas.

Afterwards, I was taken to my cabin, which I shared with John from Florida. Compact but comfortable, it featured two bunks, ensuite bathroom with shower and air-con. For possibly the first time ever, I managed to secure the lower bunk.

With everyone settled and fed, it was then time to meet the crew. On hand were Captain Gerardo, chief engineer Aurelio, chef Tony, steward Bernie, deck hands Andres, Javier and “Crazy” Luis (yes, that’s what everyone called him), and divemasters Daniel, Nacho and Jake. First up, Captain Gerardo gave a talk about the vessel’s safety features and was followed by Daniel, who gave a rundown on the following days’ activities.

No scuba certification was necessary, although a certification card was required for the submersible cage, which is lowered to a depth of 10m. Participant ages have ranged from ten to 80. However, rules are strict; no hands or feet outside the cage (why you would want to?) absolutely no touching the sharks and no alcoholic beverages until after you are done in the cage. No problem there.

The rest of the afternoon was spent readying my photo gear and getting acquainted with my fellow travellers. Virtually everyone had camera gear, but fortunately, the large table on the lower rear deck had plenty of room for the small mountain of equipment.

The next morning, I awoke to some disheartening news. An unexpected mechanical difficulty left us with a sole working propeller and our mid-day arrival had been pushed back to 9:00 p.m. Unfortunately, things do happen, but then again, this was more of an expedition than a simple pleasure cruise. Having already assembled my camera gear, all I could do was sit back, relax and dream of sharks. In the evening, we watched an old Jacques Cousteau episode featuring the elephant seals of Guadalupe. It was surreal to think we would be there in the morning.

Dramatic scenery

Arising at 6:00 a.m., it was still dark outside, so I grabbed a coffee and headed for the rear deck, which was already bustling with activity. The two rear cages were already in the water and being secured while the submersible cage was being positioned by crane off the starboard side. Despite its far-flung location, Guadalupe was not exactly serene. Off in the darkness seals bellowed; if there were seals, there would be sharks!

The rising sun finally peered above the horizon, and I had my first look at the island. Anchored off the southern west coast, the scenery was dramatic. The upper ridges blushed with colour, rugged cliffs cascaded to the water’s edge, as a cloudbank draped over the summit reminiscent of Cape Town’s Table Mountain.

As the sun rose, the colours intensified. Vivid hues of red and orange contrasted with the cool tones of water and sky, the only vegetation an occasional tuft of scraggly grass. Unfortunately, there is no time for photography; according to the board, I am slated for the first group. Gulping down my coffee, I geared up in anticipation of the morning’s adventure.

Cage diving

A maximum of four guests is allowed in each cage for one hour in duration. Getting into the cage looked a lot more difficult than it turned out to be. Once attired in wetsuit, hood, mask, boots and gloves, I made way for the rear deck to be fitted with a weight harness and “hookah,” the surface supplied air system.

After stepping down to the dive platform came the tricky part: sliding down a small horizontal ladder (over the water) on my backside, one rung at a time, to the cage. Despite visions of falling between the rungs, it proved easier than expected. Then, it was a short climb down into the cage. Once everyone was inside, the top was secured.

It proved to be a bit tight—picture four photographers of varying sizes and heights with cameras and strobes trying not to collide. I was reminded of an underwater clown car. I initially entered with a 20kg harness but promptly floated like a wayward balloon. Additional weight was necessary, so I climbed back out to change to the heftier harness. This time I sank like a stone. With everyone primed, all that was missing is the sharks.

Shark encounter

We did not have to wait long. Within ten minutes, the first shark appeared. Swimming past, it paid us no heed, exuding a serenity and grace completely at odds with its rapacious image. Mind you, I suspected things would be different if I was OUTSIDE the cage.

Everyone was mesmerized. I did not even take a single photo, watching instead, this incredible creature only a few metres away. At only 3m in length, it was small by great white standards. But hey, it was a great white!!! The ensuing hour proved amazing, with several sharks passing near the cages. They were definitely curious but exhibited no aggression whatsoever. Before we knew it, it was time for breakfast. No one wanted to leave!

For the remainder of the day, the schedule was more relaxed. As long as there was not a queue, guests could remain inside the cage as long as they liked. Being just under the surface, there was no danger of nitrogen buildup. The shark action ebbed and flowed throughout the day, with a flurry of activity followed by quiet spells. On one occasion, I signaled I wanted to exit. Just as I started to climb out, a pair of sharks appeared out of nowhere, heralding a new burst of action. Back in I went!

Bait

The sharks were not actually fed; to entice them, the wranglers tossed out lures hooked with tuna heads. The guys were experts at yanking the bait away in the nick of time, although the sharks did win on occasion! Compared to other sharks, great whites have somewhat refined dining habits. Once the bait hit the water, it was not a voracious free-for-all. If several sharks were present, they sized each other up. The biggest one fed first as the others patiently waited their turn. “I’ve seen worse table manners at an all-you-can-eat buffet,” said Jake with a smile.

The mackerel were another story, with swarms of them attacking the bait with wild abandon. They seemed to possess a sixth sense, charging towards the bait before it even hit the water.

Alas, every so often, it was necessary to emerge for meal or bathroom breaks. As getting in and out of a 7mm suit is one of my least favourite things, I opted to keep it on between cage stints. Fortunately, it was Bernie to the rescue, bringing lunch right to me on the dive deck. Talk about service!

Behaviour

Even topside, there was still plenty of action to photograph. Watching the wranglers proved to be great fun. A telltale whistle from Crazy Luis indicated a lunge was imminent. Most of the time, the bigger sharks swam up to the bait before veering off at the last second. It was the younger males that were more aggressive, in particular, one smaller male whose snout was heavily scarred. I hoped for a classic shark-head-out-of-water shot with jaws agape, but that proved easier said than done. It was astonishing how such big animals could move so fast.

At the end of the afternoon, I opted for a stint in the submersible cage. The setup with the weight harness and hookah system was the same, but this time, the hoses were connected to tanks sitting on the cage floor. There were only two of us in the cage, with Nacho along to keep an eye on things. With everyone aboard, the door was shut, and the crane swung us over the side to the water.

Within minutes, we descended to approximately 10m, which provided a totally different viewpoint of the action. Although lighting conditions were dim for photography, it was fascinating to watch the sharks’ behaviour. One came fairly close to the submersible cage, but most focused on the cage above, each with their own routine to approach it. Some would first circle around the Solmar V, while others swam out to the blue before doubling back for a pass. Seeing the sharks alongside the cage really gave a sense of scale. I later discovered the biggest one was nearly 5m long.

Research

The Marine Conservation Science Institute, a non-profit research organization, has been studying white sharks at Guadalupe since 2000. In 2002, a shark identification program was initiated. To date, approximately 241 individuals have been identified boasting such names as Bruce (naturally), Cream Puff, Gums, Stimpy, Kaiser Wilhelm, Pius Maximus, and my personal favourite—Mr. Valuelink.

During our two days at the island, ten individual sharks were observed—six individuals the first day joined by four new ones the second. Although most were not in the ID book, one specimen was recognizable: a large male missing the top of his tail, identified as Andy. Most individuals visited repeatedly, with two or even three animals visible at one time.

At dinner, there was good news; the mechanical issue had been remedied. As no one had a connecting flight the next day, the captain generously allows a late-day departure to make up for our missed afternoon. There was lots of celebrating that night. It was a good thing the Mexican beer and Chilean wine were complimentary! Bernie also made a wicked mango margherita, but I limited myself to one.

Photography gear and challenges

With regard to gear, I brought two camera bodies: a Nikon D7100 for topside images and a D810 for underwater images. Lenses consisted of a Sigma 10-20mm for the D7100, and a full-frame Nikon 16-35mm, 24-120mm and 80-400mm for the D810. The 16-35mm was used for the underwater images. With a zoom gear attached, I was able to get wider images of the cage interior at the 16mm setting, with the majority of the shark images shot at 35mm.

Nevertheless, photographing within the cage presented some challenges. Despite their large size, the cages were buffeted by the surface conditions. A few of the guests said it made them dizzy. Remaining steady was initially difficult, but it did not take long to get into the rhythm of the movement. A corner spot proved the most coveted, allowing an unobstructed view of two sides of the cage.

However, it was not the bobbing cage or people in it that created the biggest challenge; it was the mackerel, perpetually swarming around the cage or even through it. More often than not, a great image was marred by mackerel covering a shark’s eye, dorsal or tail fins. They also positioned themselves between the cage and the shark, giving the impression of shark-sized mackerel.

Exposure was also an issue, especially if a shark was nearer the cage. Even though the ambient light was bright, I used strobes for most of my images. The output was dialled down to a setting of -1 or more, so as not to blow out the highlights. Some shots were taken at higher shutter speeds in available light. Being near the surface, there was no colour loss due to depth.

Afterthoughts

Even with the long return trip on rough seas, the effort was worth it and then some. Seeing these magnificent creatures up close in the wild proved a dream come true. I wished my shark-phobic friends could see them as they really are, rather than the monsters they are portrayed as.

Although a contentious issue to some, cage-diving does help support shark conservation efforts. With shark populations plummeting worldwide, a change of perspective is essential. Once people experience them firsthand, harmful misconceptions can be cast aside. Rather than the ravenous eating machines of the movies, sharks are vital ocean predators and an essential part of marine ecosystems worldwide. Their demise would be a tragedy beyond comprehension. ■