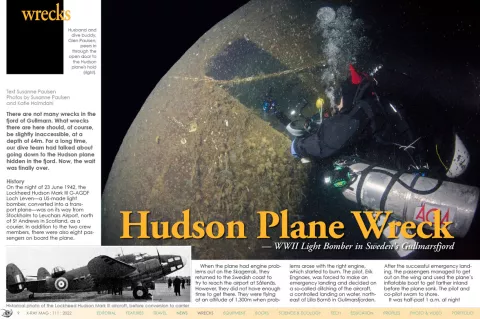

There are not many wrecks in the fjord of Gullmarn. What wrecks there are here should, of course, be slightly inaccessible, at a depth of 64m. For a long time, our dive team had talked about going down to the Hudson plane hidden in the fjord. Now, the wait was finally over

Contributed by

History

On the night of 23 June 1942, the Lockheed Hudson Mark III G-AGDF Loch Leven—a US-made light bomber, converted into a transport plane—was on its way from Stockholm to Leuchars Airport, north of St Andrews in Scotland, as a courier. In addition to the two crew members, there were also eight passengers on board the plane.

When the plane had engine problems out on the Skagerrak, they returned to the Swedish coast to try to reach the airport at Såtenäs. However, they did not have enough time to get there. They were flying at an altitude of 1,300m when problems arose with the right engine, which started to burn. The pilot, Erik Engnaes, was forced to make an emergency landing and decided on a so-called ditching of the aircraft, a controlled landing on water, northeast of Lilla Bornö in Gullmarsfjorden.

After the successful emergency landing, the passengers managed to get out on the wing and used the plane’s inflatable boat to get farther inland before the plane sank. The pilot and co-pilot swam to shore.

It was half-past 1 a.m. at night when Anders and Betty Hansson, the residents of the Linhagen farm on Lilla Bornö, heard a bang. They would soon receive an unexpected visit. Their daughters Ingrid and Lilly Andersson also woke up but were not allowed to go out. They looked curiously out of the window, and Ingrid recalled later that there were several people in the garden, as the soaked crew members were allowed to drink hot chocolate in the kitchen. In the morning, the passengers and crew were transported by boat to the mainland and beyond, via two taxis.

The incident was quickly covered up, and Swedish authorities waited till the following year to salvage courier mail and other items from the plane, to draw as little attention as possible to the incident. The explanation for the cover-up is believed to be that there were passengers on the plane whose presence would be difficult for the Swedish authorities to explain.

After the aircraft was raised and the mailbags recovered, the plane was towed out by Red Company tugboats and released into deeper waters where it still lies. Everything took place in the greatest of secrecy, but thanks to the daughter Ingrid Andersson, who witnessed the event, and also photographed everything in secret from the island, we now have access to both witness information and footage from the occasion.

Getting to the wreck site

The Flora III was waiting for us at the bridge where the skipper, Kjell Williamsson, met us with his usual good mood and cheerful laughter.

During the journey into the fjord, we had time for a briefing and some history on the wreck, planning where to place the downline buoy and some usual good stories. At the dive site, Kjell made a few sweeps with the boat over the area before my husband and dive buddy, Glen, finally threw in the large, heavy wreck marker, which would quickly and accurately hit the designated spot. Kjell navigated past the buoys. Just as we passed them, the aircraft also appeared on the monitor. This was as good as it gets.

We got ready in concentrated silence. Glen was used to diving wrecks from his time in Denmark, but I had significantly less experience, so had a few butterflies in my stomach. Curiosity and determination mixed with uncertainty and excitement. The surface was calm with only a few ripples, as we swam towards the buoys that marked the downline. We were quite a way into the fjord, and the fresh water from the stream of Örekilsälven had turned the surface waters in the fjord very brown after the recent rain showers. We prepared our cameras and lamps and began the descent.

Dive One: Like the wall of a metal house

For the first six metres, we could only see one another as weak points of light through the dark layer of fresh water, but then it cleared up. We stopped for a minute to do a final check of our cameras and equipment before continuing down the line. The next five minutes felt like an eternal repetition of the steps of breathing, equalising pressure, and balancing. I looked at my dive computer: 35m, 47m, 54m... ten metres left to go. The darkness was dense. It felt huge, this darkness. Or were we the ones that had shrunk? Despite the fjord’s otherwise embracing, protective environment and all the lights, it felt like we were two very small falling stars in infinite space.

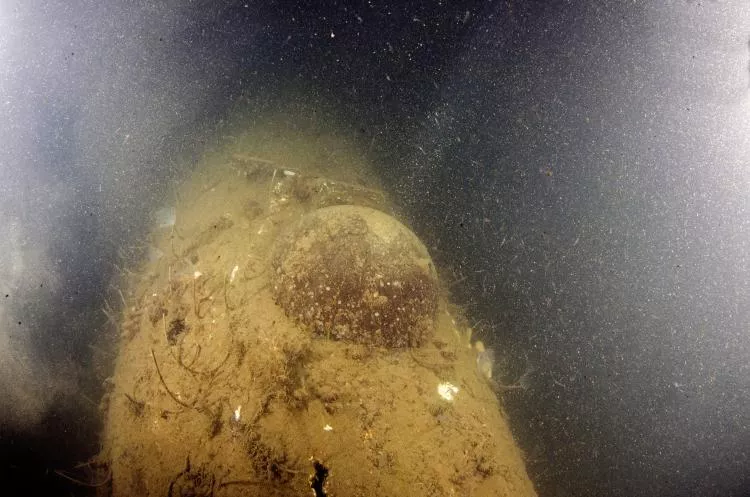

Sixty metres. No plane yet. Just the sound of our bubbles and the light of our torches sweeping down to the bottom. Slowly, we continued downwards. Still nothing. 63m. There—mussel shells and a small stinging anemone—the bottom, and the downline. The entire projectile of the wreck marker had sunken into the soft golden seabed of the fjord and only the downline protruded from the dark brown mass. There was no risk of it moving, at any rate.

We saw how just the small pressure change from our slow deceleration made the silty bottom rise towards us. Don’t stir the silt up now, I thought. We shined our lights into the dark. Nothing. I stayed by the downline while Glen slowly began to move away, trying to spot the plane. He swung his torchlight in wide circles. Like a lighthouse at night, I stayed put and guarded the downline. The plane could not be far away. A few metres maximum. I felt time ticking by. Finally, Glen waved his lamp. It was the signal that the plane had been found. I left the downline and did two fin kicks to get to Glen.

Something big and grey rose up in front of me, like the wall of a metal house. It was a strange feeling. Visibility was very poor. We were an arm’s length from the wreck and could only see a small part of it at a time. The nose and left wing appeared to be thrust down into the seabed. The rest of the plane rose from the bottom like a fallen bird.

Which it was. I saw the wing-mounted engine, which had some sort of open hatch, and continued upwards along the wing. Above me, the plane continued at a steep angle, but I wanted to see the cockpit. I followed the side of the plane down again, along its small windows. Just above the bottom, one could see straight into the open cockpit. Wow!

Heading up again, along the top of the fuselage, we found the plane’s antenna and its small glass dome. Above the glass dome was some sort of box. Placed or original? No clue. Time flew. Already 14 minutes had passed. King crab, cod and anemones lived on and around the plane, but who had time to chat with the fish now? I managed to easily ignore the wildlife and focus only on getting photos of the wreck.

It was difficult to get an overview. A large number of krill were drawn towards our lamp lights, causing a dimming effect on the light cones of our lamps, as if it were not dark enough already! I took some photos and adjusted the angle and position of my strobes a couple of times. There were many particles in the water and lots of krill that reflected the strobe light. Not easy, this... I sincerely hoped that some of the pictures would be good. Glen filmed the wreck, gliding along the fuselage like a submarine in the dark.

Seventeen and a half minutes had passed. We had to go back to the downline. We glided back over the plane and found the wing, which we then followed down again. We swam wide and Glen shined his torchlight outwards into the dark. Yes, the downline was there, right where we had left it. The ascent could begin. I felt relieved, calm, and at the same time, excited. Everything had gone according to plan.

We were picked up by Kjell and previewed the film and photos before we even got out of our suits. Inland, the light had shifted, and a magnificent rainbow emerged between the rocks. How appropriate—the treasure at the end of the rainbow. We had just found it. The atmosphere on board was as high as Gullmarn’s glittering mountain peaks. It had been an exciting day, and something had happened. My curiosity had been aroused, and I had gotten a taste of adventure.

Dive Two: A small bump on the bottom

The period after the first dive on the plane wreck was punctuated by thoughts of when we could dive there again. And again.

The first dive had felt like just a teaser—only a glimpse of something that was never fully explored. Somehow, more questions than answers had arisen, and now we wanted more. Was there a second glass dome? What did the second wing look like? And the rest of the fuselage, was it whole? We absolutely wanted to go down there again and could not stop thinking about it. The weeks went by and finally we found an opportunity.

Finding an opportunity for two more dives was not difficult. If we dived consecutive days, one after another, we only needed to find the position once, place the downline buoy and leave it until the next day. Now, if only the rest would fall into place. We needed gas. Lots of gas. And more lights, both for the rope and the cameras.

The first day of November brought 12°C (~54°F) temperatures and a gentle southerly wind of 4 m/s (8-9mph). Kjell navigated the dive boat in wide circles around the buoys of lobster traps, which lay like a slalom track along the cliffs of the fjord. No ropes in the propeller, please! We drank coffee, had a light lunch, and finally arrived at the position of the wreck.

The plane was just a small bump on the bottom, and we attempted to aim for it with the wreck marker as well as the last time. With the buoy in place, we circled around it. Hmm, not really good, about 20m from the plane. If we were to circle the plane like a compass, it would be too brief a jaunt for us, considering the amount of time allowed at depth. Up again came the 50kg heavy projectile of the wreck marker. It would be heavy now, with many metres of rope. New plan, new attempt. We circled again. “Now, you probably will not need to swim at all,” said Kjell and laughed. Soon, we would understand what he meant.

So, we finally jumped into the water. Line spool, check. Lamps for ascent line, check. Camera, check. Now, it bared down on us again: that same total darkness. This time we reached 60m after five minutes, and even then, we saw something. A tire! And the wing. Visibility was a little better this time. The rope had been laid loose and free over the wing, and we followed it until we found our cable ties, which we attached in order to clip a lamp to the rope. Below us, the projectile of the wreck marker was completely drilled into the soft sea bottom. What a hit! Thank you, Kjell.

We start orienting ourselves around the plane again. The opening of the door into the cargo area. A window. The glass dome. Above the glass dome, the small green box remained, and above it was a cylinder. There sat a majestic king crab in a nice position, peering out into the darkness. We continued around the dome and took a closer look at the cylinder. Aha! It was a fire extinguisher. The box and the fire extinguisher were overgrown and covered in silt, so they had definitely been lying there for a while. We dared not touch anything for fear of stirring up silt, but we were curious.

I forced myself to let go of any thoughts of examining the box and continued out onto the wing, which rose obliquely upwards. Glen’s torch lights were visible some distance away. I turned before I reached the wingtip, went back towards the fuselage, and continued down below it. Glen was behind me. I saw a round object. What could it be? I swam closer. Several round balls and… oops, a fishing net. Best to give it a pass.

I took a deep breath and slowly ascended. I felt a rope against my cheek. I tried to back off a bit but felt crowded, somehow. There were fishing hooks on the line, which swirled a bit when I released it. Large flakes of 70-year-old aircraft silt threatened to envelop me. “Get out of here, quick!” raced my thoughts. But I moved very slowly, so I would not get stuck anywhere.

In front of me and above me was the fuselage, and I slid slowly backward and upward, until I ended up at the wing, which descended to the bottom in front of me. Right in front of it was the ascent line, and we were back at our starting point.

Nineteen minutes now. One minute of bottom time left. Time flew down here. We made the signal for our ascent, and Glen released the lamp from the ascent line. Now, a 45-minute ascent awaited us. We made our stops, changed gas, and broke the water’s surface after 65 minutes.

When we reached the town of Oxevik, it was already getting dark. We took only the essentials home, filled up our tanks with new gas, and enjoyed a good lasagne. The day’s photos and film were reviewed, and a new plan for Sunday’s filming and photography was made. Kjell, who has won several Swedish championship titles in underwater photography, shared his advice and tips, after which we made some changes to the lighting plan for the next day. While the batteries for the lamps were being charged, we also “charged our own batteries” in the wood-fired hot tub and ended the day with some good dive stories.

Dive Three: It does not blow below the surface

After a good breakfast, we prepared for the day’s dives; however, one cannot be prepared for everything.

The rain had poured down during the night, but now, the rain had stopped again. Rain at night is good. We like that. If it always rained at night and was sunny during the day, everything would have worked. And the meteorologists had been right—more often than not. We headed out quickly and loaded the boat with a few quick transfers.

The wind was blowing. “Are you going out on this choppy lake?” asked the residents of the area. “Of course!” we said happily. “It does not blow below the surface.”

In fact, the wind was not blowing that hard—7 to 8 m/s, maybe. No white geese. We had a good tailwind into the fjord, as we screwed the dive rigs together and prepared our kit. Today, we would just jump in at the buoy. No searching. Wonderful!

Everything felt easy… but that would soon change. Kjell drove us right up to the buoys, and we jumped in. Hanging by the dive ladder, we were handed our cameras and decompression tanks. Then, we left.

We descended quite quickly and ended up a little askew of the wreck but swam on. I tried to compensate for the current but soon realised that we had a real, proper current to deal with, over which I had no control. We had to abort the dive and were picked up a good distance downstream.

Kjell towed us as we hung onto the boat ladder so that we did not have to get on board again with all the equipment, and calmly drove the boat towards our destination. It took a while. I heard Glen announce the number of yards while I concentrated on just hanging on. It was quite heavy work.

In the end, we could just let go and slide right towards the buoys. We quickly grabbed each line and hung on. It was not possible to release our grip. We got stuck there, and the sweet, brown surface waters splashed around our mouths at regular intervals. I was starting to get really tired in my arms now.

Once again, we had the notion of staying on the site longer. We decided to make a stop at ten metres to check the equipment, give the OK signal and descend.

The visibility was really zero, and I followed the downline with my hand until I hit Glen’s hand. Here, the buoys’ ropes met, and I tried to find the one that went downward. Soon, our hands followed one another, and we worked calmly and methodically downwards, with only the sense of touch as a reference.

Six metres. At least now I could see my dive computer. It was pitch black and none of our camera lights were turned on. Only the hand lamp hung in place, sending its light downwards along the rope. Ten metres. We stopped, but not for long, took a breath, turned on the lights, and checked that we were both ok. The cameras had to wait. We continued to descend, making sure to take extra time to breathe out properly.

A calmness came over me—the kind of calm that darkness and breathing under the water’s surface instils. It does not blow below the surface, as I said. It felt a bit like coming home when I saw the landing site.

The descent line had straightened out, and Glen hung the lamp in place. Lens caps still covered our lenses, and neither camera nor strobe was turned on. I concentrated on using small movements to get my technique in order and then sank down to photograph the wheel.

We followed our plan and continued heading towards the cockpit. Today, we would try to photograph and film a little farther into the wreck. The cockpit windshield had been pushed out so the crew could get out; hence, the cockpit was completely open and accessible from the exterior. One could clearly see the backrest on one of the chairs as well as some furnishings. Much of the floor was covered with bottom sediment, and I gently stretched my camera into the space and snapped off some frames. Glen followed suit and filmed it.

We also decided to investigate the tail section. We slid up past the windows on the side and continued out along the free wing—all the way out this time. We saw the engine but no propellers. Salvaged? We headed back towards the fuselage on the other side of the wing, going upwards now.

As we thought, there was no other glass dome. It had been removed during the aircraft’s conversion from bomber to transport plane. The fuselage ended abruptly with a break, just before the tail section. A round, black hole led farther into the aircraft, but our torchlights did not reach very far inside. Instead, we looked at some of the splendid king crabs that had invaded the plane. It was literally crawling with them today.

We shined our lights down to the bottom too, to discover, if possible, the missing part of the plane, but we could not really see the bottom from here. Maybe someone got a trawl stuck in the plane and tore it apart? We now moved back along the bottom of the plane, without going under it, where the fishing net was, and headed up to the starting point again. The downline hung there, with its lamp shining welcomingly to us. The gateway to the surface. Dive computer check: 18 minutes today. Good timing. Now, there was only a rather uninspiring ascent awaiting us.

The minutes ticked by so slowly during our decompression stop that I almost thought time had stopped. The fun part of the dive was done, and now I just wanted to go home and let everything sink in. However, the waves at the surface had not stopped.

After guessing what was on the dive computer for the last few metres, we were back at the buoys. We tried to give the OK signal to Kjell without letting go. Then, it was just a matter of sliding over and sitting glued to the dive ladder steps—no risk of slipping from there.

We felt quite sore in our bodies when we got back on board. Lunch and coffee gave us some strength back, as we returned home. It was a little sad that the diving was over on this adventure to the plane wreck—the small bulge at the bottom of Gullmarsfjord, with all its history. Hopefully, she stays there for a long time, awaiting us in the dark.

SOURCES:

Molander, L. (2008). Från Gullmarns inre del: Något om natur, människor och händelser. Miljöinformation i Väst. The author has, among other things, interviewed witnesses and participants in the incident.

luftfartshisorie.no. Lockheed Lodestar in Norwegian service from 1941 to 1950

Oral source: Leif Molander