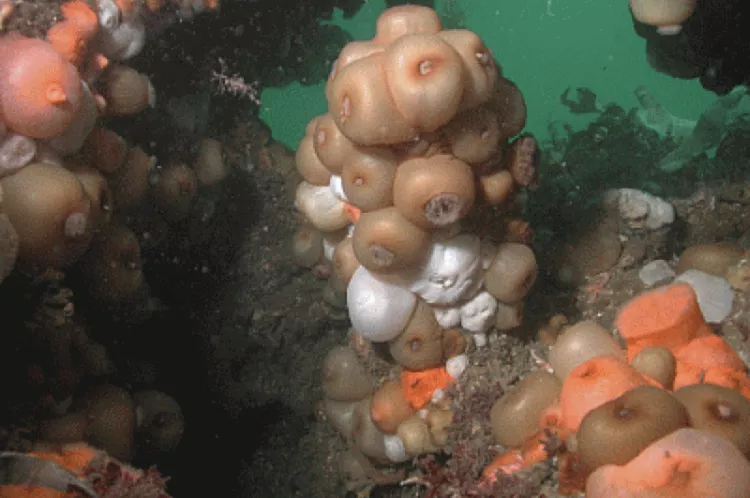

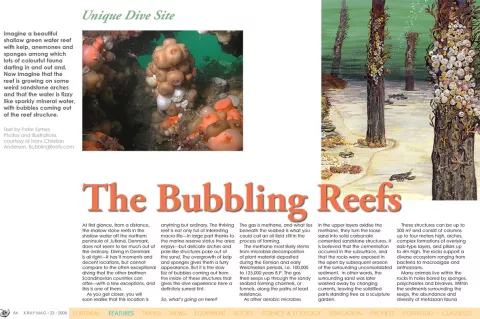

Imagine a beautiful shallow green water reef with kelp, anemones and sponges among which lots of colourful fauna darting in and out and. Now imagine that the reef is growing on some weird sandstone arches and that the water is fizzy like sparkly mineral water, with bubbles coming out of the reef structure.

Contributed by

As you get closer, you will soon realise that this location is anything but ordinary. The thriving reef is not only full of interesting macro life—in large part thanks to the marine reserve status the area enjoys—but delicate arches and pole-like structures poke out of the sand. The overgrowth of kelp and sponges gives them a furry appearance. But it is the slow fizz of bubbles coming out from the inside of these structures that gives the dive experience here a definitely surreal tint.

So, what’s going on here?

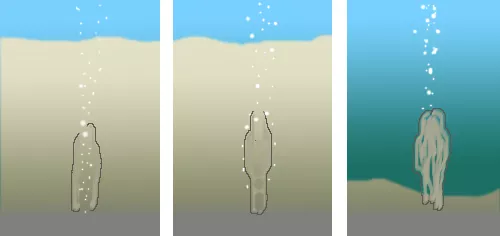

The gas is methane, and what lies beneath the seabed is what you could call an oil field still in the process of forming. The methane most likely stems from microbial decomposition of plant material deposited during the Eemian and early Weichselian periods, i.e. 100,000 to 125,000 years B.P. The gas then seeps up through the sandy seabed forming channels, or funnels, along the paths of least resistance.

As other aerobic microbes in the upper layers oxidise the methane, they turn the loose sand into solid carbonate cemented sandstone structures. It is believed that the cementation occurred in the subsurface and that the rocks were exposed in the open by subsequent erosion of the surrounding unconsolidated sediment. In other words, the surrounding sand was later washed away by changing currents, leaving the solidified parts standing free as a sculpture garden.

These structures can be up to 500 m2 and consist of columns up to four meters high, arches, complex formations of overlying slab-type layers, and pillars up to 4m high. The rocks support a diverse ecosystem ranging from bacteria to macroalgae and anthozoans.

Many animals live within the rocks in holes bored by sponges, polychaetes, and bivalves. Within the sediments surrounding the seeps, the abundance and diversity of metazoan fauna are poor—probably due to the toxicity of the hydrogen sulfide contents in the gas.

The Hirsholm islets

Hirsholmene (the Hirsholm islets) are located approximately five kilometres northeast of the port of Frederikshavn, at the tip of the Jutland peninsula. Besides the main islet, Hirshold, there is one larger islet, Græsholm, and a group of smaller islets called, Tyvholm, Kølpen and Deget, making up about 45 hectares altogether.

Only the biggest islet is inhabited, most of the time by no more than 8-10 residents though through the summer season. Yachters will visit or come over by a small ferry.

The islets are state-owned and surrounded by territorial waters. In 1929, the site was declared a Scientific Sanctuary, mainly due to the vast number of birds nesting on the islets, including a number of rare and protected species.

In 1981, the reserve was expanded to include the surrounding sea area consisting of about 2,400 hectares. The landscape is dominated by rocky embankments and banks of deposited sand and sediments along the beaches. On some of the islets, the rocks have been covered by a thin layer of topsoil formed by decomposed seaweed.

The small islets, Tyvholm and Kølpen, are almost completely barren and consist only of rocks, giving an impression of how the whole area looked in times past.

Sediment carried by currents around the islets has been deposited in some locations creating small sandy beaches, especially on the north side of Græsholm and the main Islet, Hirsholm. The site is important for marine biology research. There is a visitor centre at the site.

Diving there

There are no regular dive trips going out there, although some of the local dive shops in Northern Denmark will occasionally put excursions to the islets on their tour programmes.

The islets are only 20-30 minutes sailing with a RIB from the main coastline, so dive clubs, or dive centres, will often launch their boats from a jetty in one of the local marinas. Diving is easy with depths ranging from only 9-12 meters, although visibility can vary from the extraordinary to pea soup. ■