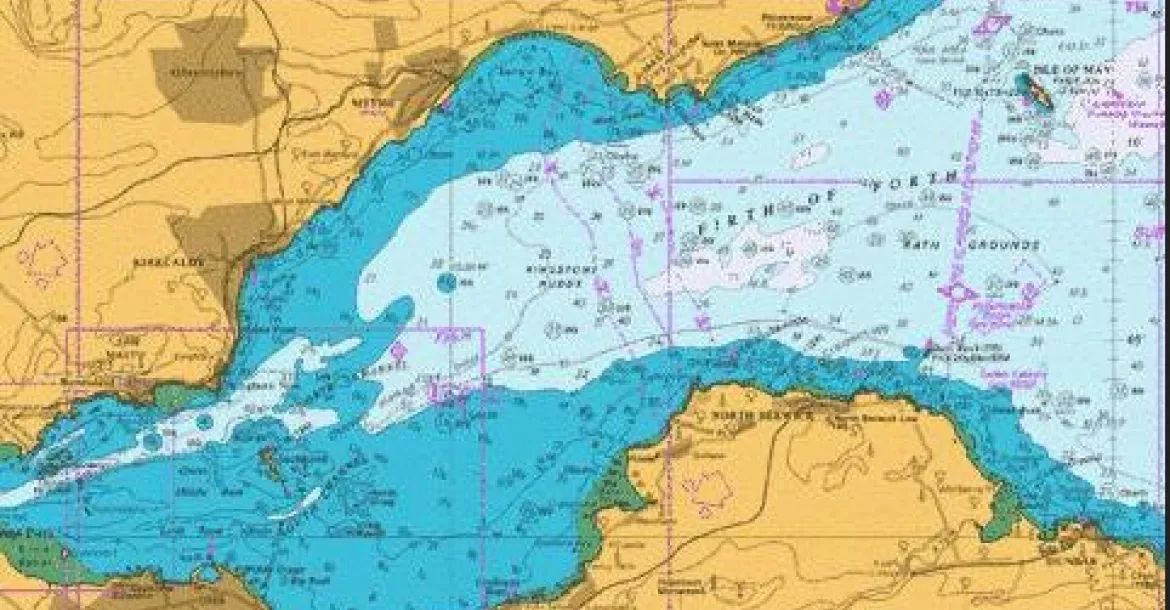

The entrance to the Firth of Forth, an estuary in southeast Scotland, is guarded by a number of islands, the two largest and most popular for diving being the Isle of May or May Isle, 7km (4.5 miles) from Crail in Fife and the Bass Rock, or The Bass, located 2km (1.2 miles) offshore and 5km (3.1 miles) northeast of North Berwick in East Lothian. Both rocky islands are usually visited on a day dive trip in which divers can enjoy three dives amidst some of the most spectacular coastal scenery in the British Isles. The other principal islands are Inchkeith, Inchmickery, Inchgarvie, Inchcolm, Alloa Inch and Tullibody Inch.

Contributed by

Factfile

Lawson Wood is a widely published underwater photographer and author of many dive guides and books.

For more information, visit: lawsonwood.com.

Although May Isle is only 57 hectares, it has been a National Nature Reserve since 1956 and is internationally important for its seabird and seal colonies. This small island has over 200,000 breading seabirds, as well as over 90,000 puffins; the island is honeycombed with their burrows. Both islands are National Nature Reserves with the Bass Rock being world famous for its resident population of gannets (Sula bassana) named after this rocky stack.

This is the largest “single rock” colony of northern gannets in the world. Seals inhabit her small caves during the breeding season, but these are usually itinerant visitors from nearby May Isle. Large numbers of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) make the Isle of May their home. During the summer months, most are found lounging on the shallow coastal rocks just southwest of the island. They have their pups in October and November, and it is these youngsters that are the most curious and make for the best interactions during dives.

May Isle

May Isle in the north has a number of shipwreck remains, with one of the most popular wrecks being the Anlaby, which is found nearby the Altarstanes (high water) landing on the western side of the island.

Anlaby wreck. This former British iron screw steamer weighed 717 tons and ran aground on 23 August 1873 in thick fog, whilst carrying a cargo of coal from Leith to Danzig. Parts of her bows can still be found in 5m (17ft) and the rest of the wreckage stretches down to the bottom of a rocky scree slope, which tumbles down from a small vertical wall to around 18m (60ft) where the muddy sand slope stretches off into the depths.

The four-blade prop, shaft, rudder and much of the stern is still fairly intact, despite being actively salvaged in 1880 when her hull was blown up to get at the engines. These sections of the stern still reach over 3m above the rocky seabed, and the wreckage inevitably has lots of juvenile fish around the periphery.

Bollards, various ribs and steel plates are littered around the slope, but it is fairly small and your interest in the wreck is soon overtaken by the fact that there are always dozens of small anglerfish (Lophius piscatorius) vying for your attention. These anglerfish are basically all mouth and no trousers! With a head over half its body length, the anglerfish has the largest mouth of all British sea fish, ringed with needle-sharp teeth. They feed by lying in wait for any unwary critter that is fooled by their camouflage; when prey gets within range, they open their mouths rapidly and food gets sucked into in!

As your time and air run out, you can ascend to the mini wall, which has long-clawed squat lobsters, tunicates and various types of anemone. This is an easy dive with little or no current and in usually good visibility as the island is so far out to sea.

Seals. A second, shallow dive with the seals is always popular and during the summer months the young “yearlings” soon approach you, frolicking all around. You can approach them as they sunbathe on the rocks, and the shallow waters to the south of the island have numerous gullies to allow you to have some amazing interactions. Many divers actually prefer to snorkel with the seals as without the associated noise and exhaust bubbles underwater, snorkelers are able to approach the seals much more closely. There are shipwreck parts scattered amidst the kelp in the shallows around the southeast corner, which you cannot fail to be impressed with when you are hanging out with the inquisitive seals.

Primrose wreck. Another popular wreck is the Primrose. This steam powered trawler ran aground in 1902 and then finally sunk around 300 metres east or the southern tip of the island in 30m (100ft). The wreck is well broken up, although her boiler, steam engine, mooring bollards and bows are still obvious, as is the stern, with her propeller rising vertically up from the seabed. This is very popular with divers as the wreckage is quite contained in a small area, allowing you to explore the site within your safe bottom time.

Bass Rock

Formed over 350 million years ago, the Bass Rock is 107m (351ft) at its highest point and is fairly circular in shape. This huge trachyte plug has sheer vertical walls on three sides and a massive tunnel that cuts the rock as it slopes more gently towards the south where a low promontory has the remains of a castle, which dates back to 1405. Still owned privately by Sir Hew Hamilton-Dalrymple, whose family has been in possession of the island since 1706.

This volcanic plug is all that remains of an ancient volcano, and you can dive around all of its sides. There is a scree slope to the edge of the western cavern, with a more muddy bottom to the east. With the huge numbers of seabirds found on the rock, the visibility can be variable due to the large amounts of guano dropping from the sky above. Whilst gannets are the predominant lodger, you can also find shags; kittiwakes; razorbills; seagulls, guillemots and even puffins, which have travelled down from their nesting burrows on the Isle of May. The Bass is visited each day by hundreds of tourists from May to September, but it is visited rarely by divers.

Most dives are done on an ebbing tide. You start your dive in the west, and keeping the wall on your right-hand side, allow the gentle current to help propel you along to the northern side of the rock. Regarded as one of the top three cliff dives in the United Kingdom, and one of the top 12 wildlife wonders of the world, it is a simple dive plan. Drop to your desired depth and just follow the near vertical wall around until it is time to come up!

As you approach the other side of the Bass Rock, you will come to an area of slack water where the current diverges and then will start to push against you. It is usually at this point that you will finish your dive.

The rock strata are quite evident, and there are nearly horizontal clefts all around the cliff face. But take care as you turn the northern corner, as the ridges now start to drop down at a steeper angle, and if you follow the ridges, you can find yourself dropping below a safe diving limit for your time underwater.

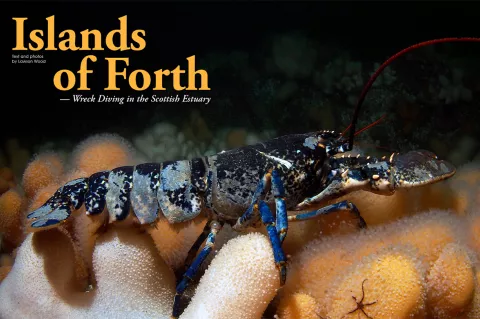

Diving this site regularly, I keep seeing the same critters, particularly one old lobster, which is dark blue and mottled with grey algae. It does have a nice hole on the wall to hide in, but it appears to spend its time wandering around, amidst the dead men’s fingers and plumose anemones. Curious volcanic outcroppings are covered in a dwarf species of the plumose anemones (Metridium senile) in both a white and orange form. Ballan wrasse (Labrus bergylta), velvet swimming crabs, small spider crabs, gobies and blennies are all over the place. What never ceases to amaze me is that these species of marine life, which are usually found on the sea floor, appear to be quite happy on a rugged vertical cliff. Adaptation to the environment is always a revelation.

Various species of nudibranch are found all over too—from the largest Dendronotus, which feed on dead men’s fingers, to the smallest Eubranchus, which lives on delicate hydroids, the Bass is a wonderland for nudibranch spotters.

There are number of small islands in the same group as the Bass, including Craigleith, Lamb, Fidra and Eyebroughy. They are much shallower and more inshore. Visibility is generally not as good, but nonetheless excellent for spotting marine life.

Dive boats venture out from North Berwick, Anstruther, St. Abbs and Eyemouth. Independent clubs are able to launch ribs at a number of sites, and navigation is pretty easy as both islands are so prominent on the skyline. The trips from Eyemouth have a travel time of around 1.5 hours, leaving around 8:00 a.m. and returning around 6:00 p.m. Daily expeditions are three-tank dive trips, including a couple of dives at the Isle of May and, with correct timing of the tides, a dive at the Bass on the way back. If you are lucky and have air left, a fourth dive at Fast Castle may be on the cards.

Gannets

The gannet (Sula bassana) is the United Kingdom’s largest seabird, with a wingspan of just under 2m (6ft). Living in the largest gannetry in the world, they have been recorded to travel 540km (330 miles) in their search for food and are quite often found off the coast of Norway. With a skull as strong as a crash helmet, the gannet can hit the water at speeds of 90mph, which actually stuns the fish making it easier to feed. The 150,000 or so birds on the Bass Rock will consume over 200 tons of fish each day, hence their distant foraging expeditions, which can last over 30 hours, leaving their mates to guard the nest.

Leaving the Bass around October, gannets are known to over-winter in the Mediterranean, even as far south as the Gulf of Guinea on the Equator. Returning in the spring, they all lay their eggs during a short period of time in May. Fiercely independent, the nests are packed tightly together, just at the edge of pecking distance and are in the region of three nests per metre. The young gain weight rapidly on their fishy diet and will voluntarily plunge off the cliffs into the sea in September before the worst of the winter storms kick in (hopefully learning to fly on the way down). Over 75 percent of the new chicks will die before they can gain their independence.

Final thoughts

If you are planning on diving along the southeast of Scotland, it is Eyemouth and St. Abbs that usually come at the top of the list, but put aside time for the local dive companies and take the day trip to the Isle of May and the Bass Rock for a greater appreciation of the great diversity of diving that is available in such a small area. ■