A once-in-a-lifetime chance to learn from the world-renowned underwater photographer, David Doubilet, brought US diver Jennifer Idol to the Caribbean island of Grand Cayman where an immersive workshop for underwater photographers offered rare insights into how to capture on camera the beautiful underwater realm of this fabled oasis.

Contributed by

Factfile

Native Texan Jennifer Idol is the first woman to dive all 50 US states and author of An American Immersion published in April 2016 by Best Publishing.

A widely published underwater photographer and dive writer with 20 years of diving under her belt, she has earned over 26 certifications.

She also creates graphic design and photography for her company, The Underwater Designer, at: uwDesigner.com.

REFERENCES:

Cathy Church. My Underwater Photo Journey. 2004. Published by Cathy Church. Page iv and Bookjacket.

Matt Unruh. Cayman Islands: A Geologic View. Spring 2008. http://academic.emporia.edu/aberjame/student/unruh1/webpage.html

Wikipedia. Bathysphere. November 2015. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bathysphere

Wikipedia. History of Photography. February 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_photography

Wikipedia. Scuba Diving. March 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scuba_diving

I was introduced to Grand Cayman through a workshop offered by Syracuse University’s Newhouse School in the Multimedia Photography and Design Department. Adjunct Professor and photographer Hal Silverman organized an extraordinary opportunity to learn from National Geographic photographer David Doubilet and underwater photographer and marine scientist Jennifer Hayes. This experience changed my outlook on underwater photography.

Doubilet led an unprecedented workshop, his first and a very rare opportunity. Together with Hayes and Silverman, they shared professional insights into how to create compelling images. I joined eight other accomplished international photographers from countries that included the United Kingdom, Germany, China, Mexico, Spain and Switzerland.

The workshop leaders organized the event in association with a university program, and expected to teach beginner photographers. They were delighted to learn we were an ambitious and experienced group, so they adjusted the workshop to reflect an in-depth look at professional underwater photography. Silverman created an immersive workshop to fill a big gap in educational opportunities for advanced underwater photographers.

Planning the dives

We began planning our dives with photography objectives set each day by classroom lessons at Sunset House Hotel. Hayes and Doubilet revealed their photo techniques for composition, lighting and story making. Doubilet creates his imagery with the mantra: “Dream. Think. Shoot.” I agree with his belief that if you are not creating what you want, dream a better dream.

Never before have I heard such an honest portrayal of professional underwater photography. Doubilet provided insight that included his opinions on photography. In the workshop, he noted how images have the power to illuminate and open people’s eyes to the sea. As underwater image makers, he reiterated our ability as voices to protect the environment and the oceans.

To build their stories and make the most of limited time, Doubilet and Hayes research every location before they leave for a trip. For this workshop, they shared their insights into Grand Cayman. We learned what wildlife we would encounter in each dive and how they would behave. As an aquatic biologist, Hayes shared her insights so we would know what marine behavior to expect on each dive.

Doubilet and Hayes have spent a career learning about the sites of Grand Cayman. Doubilet’s famous image of stingrays at the Sandbar made this an iconic destination. Before his image (which showed both above and below water in one composition), only underwater images of stingrays were shown of this site. By uniting the two worlds, the relationship between the above water and underwater was emphasized. This image captured the imagination of tourists.

For wrecks, we were clued into the best features to capture. Ships often appear indistinct and look more like texture than structure. The strong lines in the wrecks of Grand Cayman help to create recognizable depictions. We focused on the bow and sterns of the ships, the most distinguishable features. Superior visibility also contributed to being able to photograph a recognizable ship, rather than details protruding from green water.

We gathered each evening following our dives to review images, discuss the next opportunities and learn editing techniques from Silverman. This week taught us not just how to compose our images, but also what to do with them afterward. We used professional editing software by Adobe to use subtle changes in contrast, lighting and color to develop our images. A bad image cannot be made into a great image, but an image can be enhanced to reflect our experience of a subject.

Origins of photography

Doubilet felt our understanding of underwater photography would be helped by a refresher in photo history. Knowing how photography developed contributed to our understanding of modern optics. Moreover, photography is a relatively new and ever-developing technology.

I saw the first evidence of a photograph on display in the Harry Ransom Center in Texas. French inventor Joseph Niépce created this image from the window of his studio in either 1826 or 1827. Just a few years later, photography was commercially introduced in 1839.

Image making has come a long way in a short time, much like scuba history. Since we first dreamed of exploring underwater, we also sought to create reproductions of real life through images. William Thompson took the first underwater pictures using a camera mounted on a pole in 1856. George Eastman revolutionized photography when he invented roll film in 1884. Shortly after this invention, Louis Boutan became an underwater photographer using surface supplied hard hat diving gear in 1893.

Developments in scuba technology revolutionized underwater image making. The first record of Man descending in a diving bell comes from the 4th century BC. A bathysphere showed a naturalist marine life for the first time in 1930.

Our scuba regulator was first invented in 1864 by Rouquayrol and Denayrouze, and refined to much the way it is today by Jacques Cousteau and Émile Gagnan in 1942, making the underwater world accessible to millions.

We benefit from this technological innovation and are lucky to use it for individual exploration and photography. This also contributed to the proliferation of photography we know for Grand Cayman.

Rich history

The workshop brought my awareness of the storied history of professional photographers who visit Grand Cayman to the forefront of my thought. I began to consider Grand Cayman differently and I noticed how nearly every remarkable photographer seems to have visited Grand Cayman to create images of the diverse reef system. Not only was I thrilled to learn from the most revered of my role models, but I was equally excited to meet notable photographer Cathy Church.

She moved permanently to the island in 1987 and has been teaching underwater photography in Grand Cayman since 1972. Church is recognized for a number of awards, including being inducted into the Women Divers Hall of Fame in 2000 and receiving a NOGI award in 1987. I hoped to meet her on this trip and was fortunate she was in her studio during my visit.

Cathy Church’s Underwater Photo Center and Gallery at Sunset House Hotel is the premier duty-free camera store on the island. This dedicated photo store provides every need for photographers from amateurs to professionals. As I walked down the stairs at the end of the building to her studio, my anticipation grew. Once inside the gallery, I was immersed in her underwater world. Original prints filled the walls of one room and photo equipment dotted another room.

She shared some of her stories with me, including her new artistic pursuits with photo manipulation. She has produced images for numerous publications, but is also creating abstract fine art pieces built from composite images. I admired a black-and-white barracuda image and was reminded of the diversity in the work we were creating in our workshop. We developed black-and-white images that were strong because of their composition, contrast and shape.

Photo ops abound

After I learned about the proliferation of image makers who visit the island, I took this thought a step further and began to address a question of photography in the Caribbean. Why is Grand Cayman so highly revered as a photography destination?

The largest of the Cayman Islands, Grand Cayman is not a volcanic island, but instead the top of the Cayman Ridge, a submarine mountain range formed by colliding tectonic plates. Flora and fauna abound on the island. I observed iguanas and parrots every morning before our dives.

Dubbed a living aquarium, the island features diverse photographic opportunities. Since the island is composed of limestone and lacks sediment runoff, superior visibility defines the waters. With easy accessibility to diving and photographic support, any photographer is sure to create beautiful images.

This location is like an underwater studio stocked with all the tools necessary for image making. The diversity also supported our ability to create a broad body of work.

Wildlife encounters and behavior

Animal behavior dominates the underwater landscape, from reproductive cycles to feeding activity. The famed Stingray City and Sandbar introduce visitors to guaranteed southern stingray encounters. Visitors from cruise ships snorkel with these island stewards, each bearing high economic worth and hence protection. This experience helps snorkelers connect with sea life.

We spent several wonderful dives observing these animals. I even observed award-winning photographer Christian Vizl surrounded by stingrays. He was used to this subject, having photographed them many times in Mexico and felt at home on the Sandbar.

Every marine encounter was stunning. The first time I observed a cleaning station was on this trip. I saw wrasse swim in and around a black grouper’s mouth as I approached a pinnacle. Great barracuda hovered beneath our boats for cover and disguise as they waited for an unsuspecting fish to swim below, unable to see him as he strikes like lightning right from the sun overhead. Houndfish hovered near the surface, hoping for a meal.

Large subjects

Wide-angle photography opportunities include large animals, reef scenes and wrecks. I photographed tarpon in Devil’s Grotto, a hawksbill sea turtle on Ironshore Gardens and the most beautiful red, orange and yellow sponge scenes at Orange Canyon.

Two wrecks dominate the underwater scene, the Doc Polson and ex-USS Kittiwake. Both are easy to swim through and serve as artificial reefs. On one of our dives, we saw telecommunications cable that a ship like the Doc Polson would have laid. This small ship was relatively shallow in 17m (55ft) of water and was easily explored on one dive.

The Doc Polson features more reef growth than the ex-USS Kittiwake because it was sunk in 1981. The larger ex-USS Kittiwake is the most recent artificial reef in Grand Cayman, sunk in 2011. The white paint has since faded, so this wreck appears like a dark shadow on the sand.

The ex-USS Kittiwake is a large Chanticleer-class submarine rescue vessel in 19m (62ft) of water. I could easily spend several more dives on this wreck. Hayes and Doubilet took turns as models for us on this wreck. The stern loomed over Hayes in one of my photos, demonstrating the large scale of the ship.

I dove with published photographer Jenny Stock from the United Kingdom. Together, we spent time swimming through the stack midship. Inside, we found the engine room, a hyperbaric chamber, and seemingly endless rooms.

Tiny animals

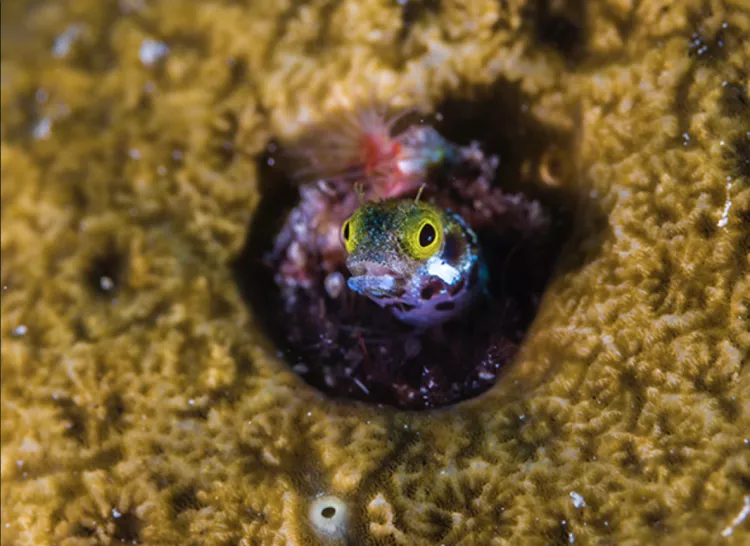

In our workshop, we explored some of the abundant macro photography subjects. We saw male yellowhead jawfish incubating eggs and keeping them in their mouths. With a little patience, we were all able to find jawfish spitting the eggs out of their mouths. They live in holes in the sandy areas. To an untrained eye, the bottom would just look like sand and rubble, but to those looking for jawfish, an entire community of fish rising and falling from holes was observed.

Secretary blennies and porcelain crabs also captured our attention. I swam over a rocky barrier and found lobsters hiding in crevices. Before this trip, macro photography was my least favorite endeavor. The shallow water and ease of diving helped me leisurely learn what to observe and how to photograph these subjects. By the end of the trip, I was excited to spot every small fish I could find. I was even lucky enough to find a slender filefish drifting away from its gorgonian cover.

I was careful to exercise good buoyancy, especially with macro photography so I would not damage the reef structure with contact. If you struggle with hovering perfectly, I find sandy areas a good place to find a safe spot that won’t damage habitat. There, I was able to focus not only on the jawfish but on translucent fish like the bridled goby.

Diving variety from one dock

While most of our dives were conducted from boats, we also explored the shoreline. No trip to Grand Cayman would feel complete without visiting the mermaid statue, Amphitrite—Siren of Sunset Reef. A small replica stands outside the restaurant at Sunset House Hotel. Recent sculptural gardens in the Caribbean have redefined the underwater scene as an artistic statement and artificial reef environment. Grand Cayman’s famous mermaid, created by Canadian artist Simon Morris, has been drawing visitors since it was carefully placed underwater in 2000.

I enjoyed spending more time on shallow shore dives to find macro subjects. At the end of our trip, I snorkeled from the coastline at dusk and saw squid dancing with the current. They gleamed with bioluminescent pulses as if waving farewell.

What you need to get started

To appreciate a place like Grand Cayman for its photographic opportunities can be daunting. An abundance of tools makes image making accessible and overwhelming. I strongly recommend small point-and-shoot cameras for beginner underwater photographers. Cameras are extremely distracting and can lead to poor buoyancy, lost buddies and low-air situations.

Manufacturers are all making competent cameras, so the choice in equipment depends largely on your budget and the time you invest to learn the equipment. Whatever camera system you invest in, get familiar with using it on land first. This will make your underwater time less stressful and more productive.

Most cameras require a camera-specific housing to make them waterproof and to operate the buttons. Some manufacturers like Canon sell plastic underwater housings for their smaller cameras.

While we primarily used DSLR cameras to create large professional images, mirrorless cameras are becoming more popular. Since they are smaller than DSLRs, they are easier to carry and use underwater. They rival the quality of a DSLR and also feature interchangeable lenses.

On our trip, I saw a multitude of professional cameras in use with a variety of housings. Amusingly, it seemed as if we had more equipment than divers on our boats.

Center of Caribbean photos

Grand Cayman is not just a beautiful Caribbean destination, but its rich photographic history and diverse opportunities make it a top photo destination.

Plan your trip to include some of my favorite photo subjects: the ex-USS Kittiwake, the 272kg (600lb) bronze mermaid Amphitrite, the silvery tarpon in Devil’s Grotto and the amazing colors of Orange Canyon.

I participated in a once-in-a-lifetime workshop with David Doubilet, Jennifer Hayes and Hal Silverman. Photographers looking to learn techniques in Grand Cayman can learn from Cathy Church in her photo center and gallery at any time. ■