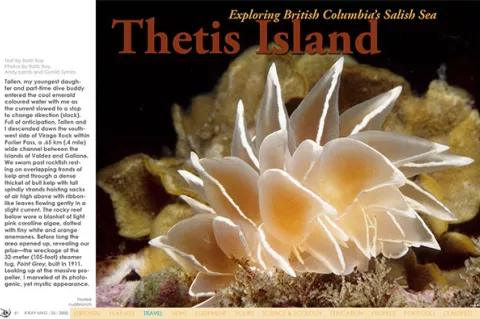

Tallen, my youngest daughter and part-time dive buddy entered the cool emerald coloured water with me as the current slowed to a stop to change direction (slack). Full of anticipation, Tallen and I descended down the southwest side of Virago Rock within Porlier Pass, a .65 km (.4 mile) wide channel between the islands of Valdez and Galiano.

Contributed by

We swam past rockfish resting on overlapping fronds of kelp and through a dense thicket of bull kelp with tall spindly strands hoisting sacks of air high above with ribbon-like leaves flowing gently in a slight current.

The rocky reef below wore a blanket of light pink coralline algae, dotted with tiny white and orange anemones. Before long the area opened up, revealing our prize—the wreckage of the 32-meter (105-foot) steamer tug, Point Grey, built in 1911. Looking up at the massive propeller, I marveled at its photogenic, yet mystic appearance.

During February of 1949, while in-route with a load of railway cars in tow, the Point Grey tragically struck Virago Rock in thick fog. To make matters worse, the barge in tow rammed the tug from behind, pushing it higher onto the rocks. There the abandoned vessel remained until it rolled over and slipped beneath the surface during a storm in the early 1960s, coming to rest upside down in 10-15 meters (33-49 feet) of water. In late February of 1993, strong currents and stormy weather once again wreaked havoc, breaking the Point Grey in half and flipping the bow section right side up.

Tallen snapped me back to reality as she waved, beckoning my presence. She hovered over the Underwater Archeology Society of British Columbia’s (UASBC) plaque, pointing down. It has always amazed me how well some people can utilize facial expressions underwater; Tallen is one these people. She gleamed with a big smile on her face, pointing at four little bright red juvenile Puget Sound king crabs huddled tightly together. I tried to return the smile but was lucky to keep my regulator mouthpiece from falling out.

I pointed at my camera housing, then to the huge prop, signifying ‘wide angle’. She shrugged, and off she went to check out the rudder. Marine life covered the two remaining prop blades and the third, which had broken off, was too well camouflaged to identify.

Each giant blade housed an array of invertebrate life, making me wish I would have also brought my macro system. Orange social tunicates, small cup corals and yellow zoanthids shared one of the blades with frosted nudibranchs, painted greenlings and dozens of decorator crabs, all protected by a light covering of red and green kelp, closely resembling leaf lettuce.

We continued down the port side over a caved-in hull with iron ribs stretching across below us. Upon each rib perched a population of tall white plumose anemones, feather stars and clusters of odd-looking swimming scallops. Wary lingcod and immense cabezon, all nestled safely within the tangled wreckage, eyed our every move as we swam over.

Aware of our time restraints and not wanting to experience the 9-knot current this area is known for, we hurried to the bow section. Yellow, orange and tan sponges helped to create collages of marine art along the way using what were once jagged pieces of hull for canvases. Spotting a rusty circular area, perhaps formerly housing a porthole, Tallen posed for a portrait shot, sticking her face through the opening, with tongue hanging out. What a ham…

Altogether, I counted six different species of nudibranchs, five species of anemones and four different kinds of crab. After another long glance at the mammoth propeller blades, we ascended to the bull kelp for our safety stop. Overall, our depth was a between 10-15 meters (33-49 feet) with moderately good underwater visibility, rendering it adequate for close, wide-angle photography.

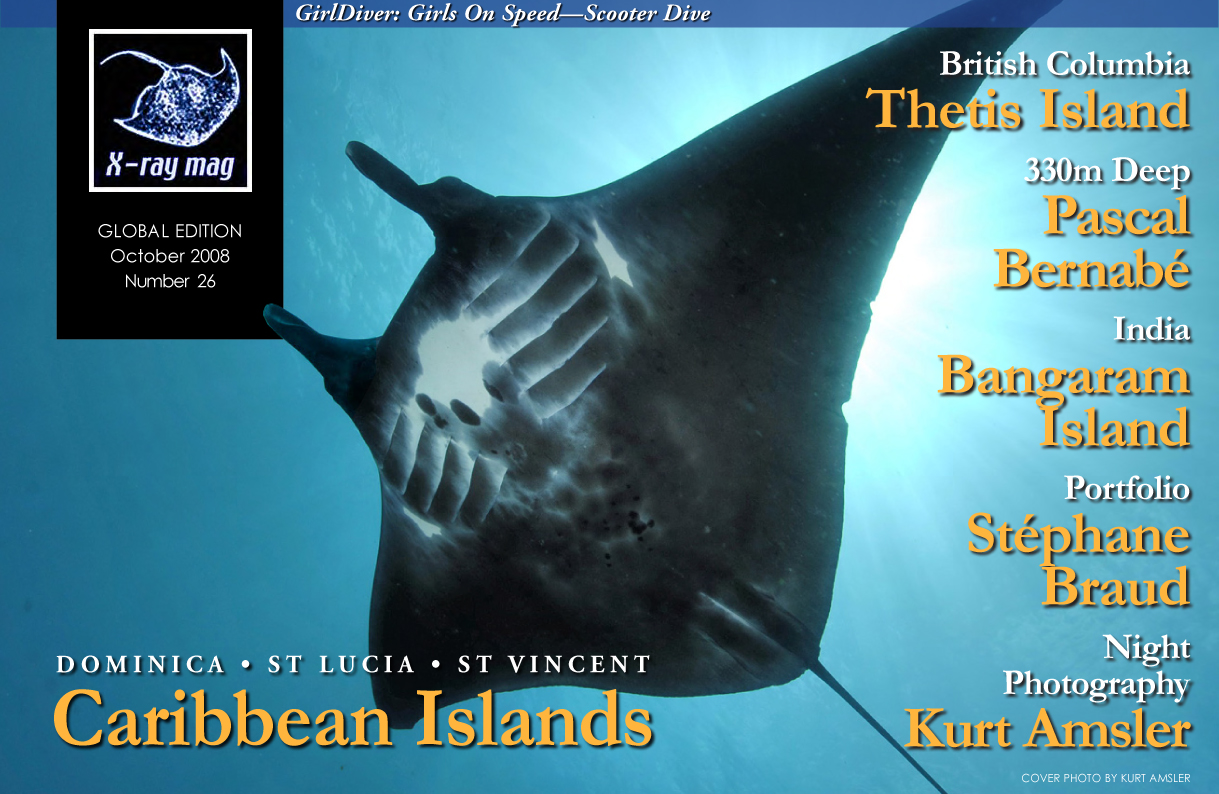

This is just one of eight excellent sites divers have to explore when visiting Porlier Pass, part of Trincomali Channel and a dive region commonly referred to as the Chemainus and Thetis Island area, located on the southeastern side of Vancouver Island in British Columbia Canada.

“The local First Nation people refer to this area as the Salish Sea,” informs Peter Luckham, owner and operator of the dive charter business 49th Parallel. “The Hul’qumi’num Mustimuhw people often refer to that way because the word tends to capture the notion of the Coast Salish people and their traditional territory—inland waters stretching from Puget Sound to Johnstone Strait.”

Peter has been diving in this area for over nine years and seems to genuinely enjoy introducing divers to underwater paradise year round. “Most are current dives, but with sufficient planning and guidance they are easily within reach of most divers. The sheer variety of sea life is staggering. All are boat dives excepting Pringle Park and Coons Bay. The bottom at most sites is literally carpeted with white plumose anemones or green and purple sea urchins.

When you see how many lingcod hang out here, and not just small ones, you begin to wonder why there is a fishing closure. Once you pull yourself away from the splendor of this spot and start looking closer, you start to see the really interesting stuff, like big crusty Puget Sound king crabs, war bonnets hiding in crevices, sponges, sea pens, and beautiful coloured nudibranchs of all shapes and sizes. The two wrecks here are a glimpse at marine history that you will not find anywhere else. We even found cloud sponge one day in the middle of the pass.”

As we headed to our next dive site in Stuart Channel (low current area), closer to the town of Chemainus on Vancouver Island, Peter passionately continued to tell us about his business: “From the Chemainus community dock, we have six good sites within 20 minutes of the Stuart Channel area and an additional six sites within a 30-40 minute boat ride. I can pick divers up at the community dock in Chemainus or on Thetis Island.

Eight more sites are available to us on the Stuart Channel side and in Trincomali Channel, all within a 30-40 minute boat ride. Porlier Pass alone has eight sites, including three great wall dives!”

To accommodate divers, Peter has the Fat Cat, a 17-foot catamaran for individuals and couples and the Xihwu Explorer, a 37-foot Alwest for groups of up to ten. His dive range extends as far north as Gabriola Passage and as far south to Sansum Narrows, including all islands between.

It was approaching dusk as we arrived at our next site, “Xihwu Reef”, meaning red sea urchin reef. Most know it better as the location of the 100 foot long Boeing 737-200 jet plane, scuttled as an artificial reef in 2006 by the local dive community and the Artificial Reef Society of British Columbia (ARSBC). The plane sits 15 feet off the bottom on a custom built stand in 90 feet of water. All windows and doors have been removed and the forward and aft cargo bays are open.

Although wreck certification is recommended for penetration, Tallen and I entered and swam around with ease. The body of the plane is about 12 feet in diameter and the distance between the front and rear exits are about 65 feet. Wingspan is 100 feet between wingtips.

First Nation Carvers, Gus Modest of Kuper Island and Doug August of Cowichan created the markers used to honor the reef and as a tribute to the Hul’qumi’num Mustimuhw people. One marker was a large red sea urchin mask, placed on the nose of the plane. The other was a replica, used as a prize in the initial fundraiser when sinking the plane in 2006.

The mask on the front of the plane dwarfed Tallen underwater as we explored the plane’s cockpit, taking turns in the area where countless pilots once flew this mighty silver bird. Here, the maximum depth is 70 feet. A 95-foot depth can be found mid-ship and 150 can be reached off the stern or rear of the jet. Angling upwards, at 27 feet tall, the tail section was only 40 feet deep.

Our good friend Andy Lamb, co-owner of the Cedar Beach B&B on Thetis Island has recorded over 100 different species of critters on the plane as of July, 2008. As a zoologist and co-author of two marine identification books, Andy also offers marine education workshops and loves to dive on the plane whenever possible.

If air supply permits, there is also a nice reef nearby, boasting a healthy supply of critters. Octopus, wolf eels, shrimp, sea cucumbers and rockfish are often seen, along with the occasional sea lion or harbour seal, offering breathtaking encounters!

Andy and his wife Virginia put us up for the night at Cedar Beach in northwestern style cozy rooms with thick down comforters. Dinner was glazed chicken with an assortment of fresh vegetables, topped off with a scrumptious dessert. Afterwards, we sat around in their large recreation room while a fire warmed us, listened to Andy tell about his experience teaching marine education at the Vancouver Aquarium.

Tallen also volunteered for many years at the aquarium taking scores of school kids on humorous, fun tours through the aquarium. I once saw her with a group of six and seven year olds walking by like crabs as they headed for the crustacean tanks.

When Virginia mentioned the night before that we would enjoy the view, I had no idea how scenic it would actually be the next morning! In the distance, I could see traces of fog lingering around the Southern Gulf Islands.

After a delicious homemade breakfast, we loaded up our dive gear, along with a hearty lunch Virginia had made for us, complete with soup, sandwiches and cookies. Andy took us down to the marina where we transferred our gear onto Peter’s larger boat. The cabin was very spacious and warm, with a head and plenty of changing room. A fresh water hose was available for rinsing gear and cameras on deck.

Andy joined Peter and I for a dive on the historic wreck of the British Bark Robert Kerr, located north of Thetis Island between Miami and Ragged Islets, not far from the wreck of the Miami, which sank in 1900 after hitting Danger Reef. The once proud 190 foot wooden vessel Robert Kerr was built in Quebec in 1866 and originally sailed as a three-mast passenger carrier for Hudson’s Bay Company across the ocean from Great Britain to the Pacific Coast.

Historic records indicate the Robert Kerr was also used to rescue 150-200 people during Vancouver’s great fire of 1886. The vessel was later sold and transformed into a coal carrying barge in 1885. In March of 1911, while in tow from Ladysmith to Vancouver with a full load of coal, the tug towing the Robert Kerr wandered off course during the middle of the night, causing the barge to hit Danger Reef, thereafter quickly sinking.

Today what’s left of the barge sits upright in 35-70 feet of water with deck knees giving the structure a ghostly skeletal feature. Its cargo of coal lies scattered about the wreckage, blending in with the terrain, but the ship’s captain and two iron masts are quite distinguishable even though they wear several layers of marine growth.

While Andy occupied himself with search out hiding critters in the ship’s hull, Peter and I swam out away from the stern to examine the nearby debris field. Peter pointed out an old door key plate in the mud, careful not to disturb it. We came across the ships’ double mast ring next, lined with a patrol of copper rockfish.

Peter and I gathered up Andy and headed for the bow section. I found Andy to be a lot like Tallen when diving, distracted by anything that moved and curious of what resided in every nook and cranny! I have learned over the years that this is actually a good thing, because both Andy and Tallen have discovered quite a few new subjects for me to photograph over the years.

During our gradual ascent up the reef, we came across several delicate rose stars, white-spotted anemones and giant swimming nudibranchs. Visibility proved to be viable for both wide angle and close-up photography.

Active Pass

My husband Wayne Grant joined me later in the year to explore several more dive sites Peter and Andy, introducing us to Active Point Pinnacle. The reef starting out shallow then dropped off to form a nice wall around 50 feet. Although the wall continued deeper, Wayne and I followed Andy and Peter for a while, then went off on our own, while Andy busied himself with his lingcod survey and Peter checked the anchor.

Visibility was about 30 feet. After seeing the abundance of invertebrate life, I was happy I had decided to use my 50mm macro lens instead of the wide angle. I often hear about macro photography being so easy, but I find it quite challenging when using a big SLR housed camera, especially when trying to get close to a tiny critter the size of your little finger!

The lens does however, allow very close focusing, but to get any form of light on the subject, strobes often need to be twisted awkwardly around in uncomfortable angles limiting a clear view.

Alas, the contortion is usually worth it in the end, especially with all of the juvenile rockfish, dwarf calcareous tube worms, black-eyed gobies, hydroids, and spaghetti worms we saw on the dive. Wayne was great at lighting my path with his HID light, turning a deeper, darker dive into a sunny day. When not modeling for me, he likes to float just above me pretending he is my shadow.

Several snails of varying shades of lavender were nestled on a cluster of yellow eggs about the size of corn kernels. Feather stars seemed to cover the site in general, as if someone had planted golden brown sea lilies everywhere. Lined chitons, huge plumose anemones, sea cucumbers, tiger rockfish and perch were also seen. As for nudibranchs, there were a few very small ones, but the white frosted nudibranchs seemed the most plentiful.

Back on the boat, it didn’t take us long to devour the yummy lunch Virginia had prepared. Peter filled us in on the areas potential. “We easily have more than a dozen good dive sites to choose from now, most within a short run from Thetis Island. If the weather is bad around Porlier Pass, we always have sites in Stuart Channel. Then, there is Trincomali Channel, but it can be current dependant in places.”

“The main part of Active Pass is exceptional,” added Andy. “I have done a lot of diving there and know the area well. You would love the colors for your photography!”

Escape Reef

Escape Reef was our second location. Visibility looked a bit better here, but I wanted to leave my 50mm lens on anyway. We followed the rocky terrain down to 70 feet where it unfolded into a sandy sediment bottom. Each section we came across offered something different.

Hiding under huge boulders were various rockfish, lingcod and kelp greenlings. Swimming scallops, glassy tunicates, rock scallops decorated in yellow boring sponge, clung to the rocky structures.A strange color variation of swimming anemones caught my attention; I found a whole group together, when I ventured closer.

Wayne found an area where the ocean floor seemed to move! Closer examination revealed hundreds of brittle stars. Sunflower, leather, rose and sunstars added rich colors to the scenery. As we ascended to do our safety stop, we discovered very different critters on and around a wall!

This was perhaps even more colorful than the deeper depths, yielding yellow and white sponge, more anemones, small fish, featherduster worms, kelp crabs and a slim worm habitat. I found it hard to get out of the water when I discovered a heart crab at the end of my dive! Maybe it was the 47°F water temperature that helped me to exit.

Peter said later that he had found stubby squids while checking out the soft bottom during his dive. Andy found several structures on his dive, large enough to swim through! Peter instructed us to leave our gear onboard, and he would fill our tanks.

When asked what other wrecks were available to dive, Peter explained, “We have the 60-meter (190-foot) long wreck of the Del Norte (1868), a side-wheel schooner at the northeast entrance to Porlier Pass, the HMS Panther (1874) at Wallace Island and the Peggy McNeill (1923) a steam tug in Porlier Pass to choose from.”

Andy had a map of the area on his wall showing all the dive sites he and Peter have explored, all colour-coded with push pins denoting ok, good and excellent sites. There must have been a hundred locations marked.

I encourage visiting divers to plan for a two to three-day visit in order to truly be able to sample some of the areas unique sites. There are several dive charter operators available and numerous bed & breakfast inns ready to accommodate, most requiring reservations. Visiting divers can carpool in their own vehicle, taking an automobile ferry from mainland Vancouver to Nanaimo or Swartz Bay.

When traveling during the summer months, ferry reservations are highly recommended. Chemanius is located 19 miles south of Nanaimo and 50 miles north of Victoria. When not diving, check out the local museum, 37 murals and 12 sculptures along with art galleries and antique shops. Cedar Beach B&B also offers use of their kayaks to their guests. ■