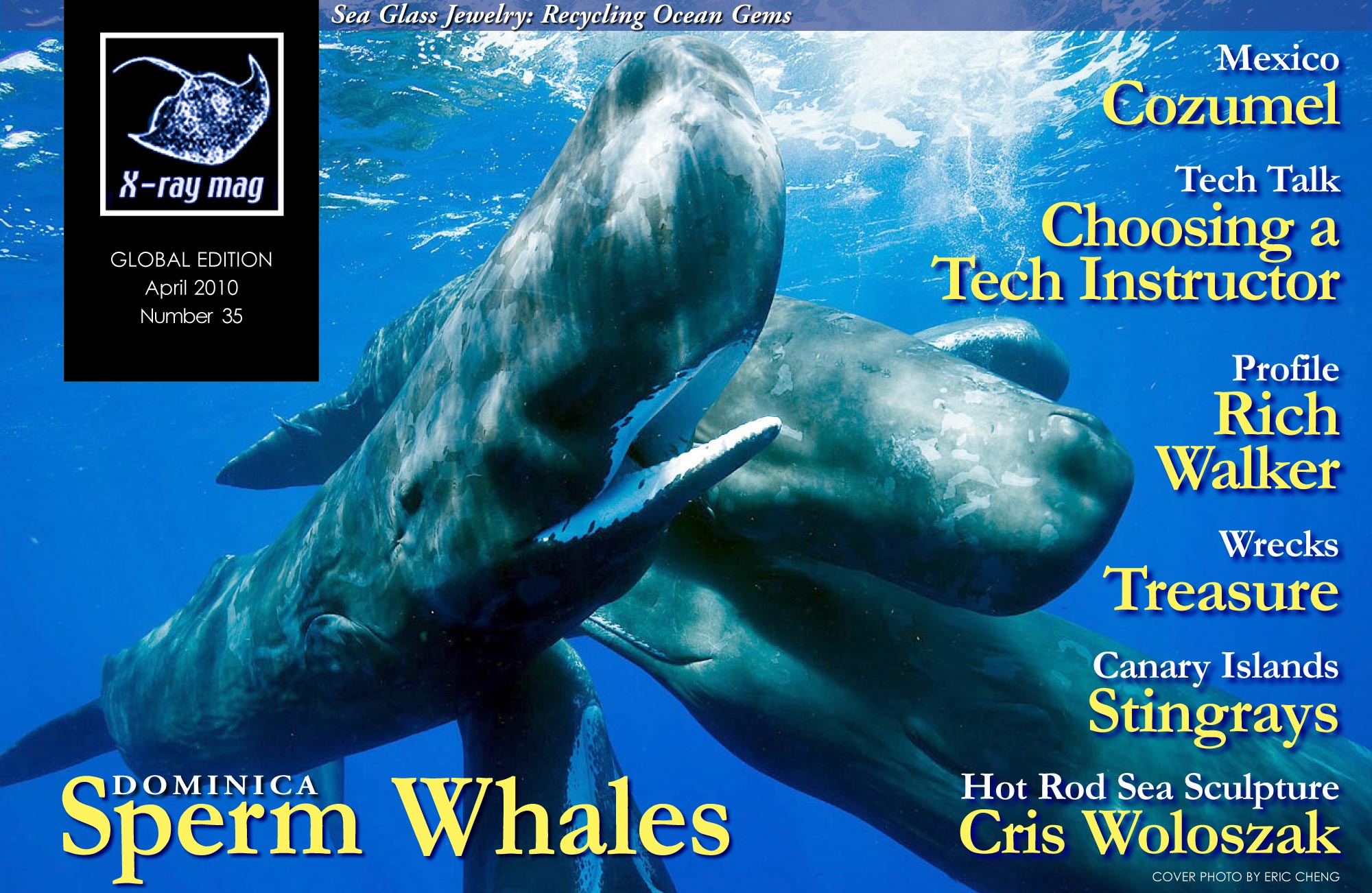

The memory of my first sperm whale encounter is so visceral that I can almost feel myself there again if I close my eyes. As is common to most whale encounters, it wasn’t a particularly long one; the juvenile male merely drifted by slowly, effortlessly, turning on his side so he could stare at me with a tiny little eye before disappearing into the blue. To him, I was probably nothing more than a passing curiosity—an awkward sack of meat wrapped in neoprene—but the experience was an overwhelming one for me, and I knew that I wanted more.

Contributed by

The sperm whale is the canonical whale, its form immortalized by books and drawings centuries old. When you ask a child to draw a whale, it is likely that what will come out of her developing mind most likely resembles a sperm whale, an animal with a huge, box-like head and tiny pectoral fins whose evolution seems to defy logical explanation.

Given that there seem to be sperm whales distributed all over the world, why is it that they are so shrouded in mystery? Most whale enthusiasts I know talk fervently about humpback whales, but grow quiet when sperm whales come up. Few of them have ever seen a sperm whale, even on the surface. Sperm whales are not rare. I’m told that sperm whale populations are quite healthy, and that their geographic distribution is wide, which means that they can be found in almost every area of the world.

I don’t mean to state the obvious, but it turns out that all you have to do to see a sperm whale is travel to where they live. Although mature male sperm whales do migrate from polar regions to mating grounds in the tropics, juvenile and female sperm whales do not migrate, making it much less probable that you will have a random encounter with a sperm whale unless you go to the places where they live.

So where do sperm whales live?

Sperm whales live where their food lives. I’ve had luck at both of the places I’ve traveled to in search of the mighty cetaceans: Ogasarawa, a group of islands 620 miles south/south-west of Tokyo, and Dominica, an island in the central Caribbean. Both island chains sit at the intersection of grinding tectonic plates and have ridgelines that drop off steeply under the ocean’s surface. In both locations, sperm whales are found on the surface along underwater topography about 1000 meters deep, where their prey — large and giant squid — live.

In Ogasawara, I photographed a sperm whale with an Architeuthis dux giant squid carcass in its mouth — a first, I’m told — but it was in Dominica that I had the most incredible whale encounters of my life. Scar, a 10-year old male sperm whale, has been initiating human encounters almost literally since the day he was born. Andrew Armour, our local guide in Dominica, has spent countless hours in the water with Scar and believes that Scar has been a “gateway whale” in that others whales in the area seem to also tolerate human presence in the water.

Getting into the water with Scar for the first time was a bit intimidating. Although he is a young male, he is still about ten meters long and comes barreling at snorkelers, sometimes not stopping until physical contact is made. Indeed, I spent as much time swimming away from Scar as I did trying to photograph him, and in the end, I ended up putting my camera down and giving him a good rub. Scar closed his eyes, and his huge body wiggled slightly under my hands, like a 12-ton puppy might do in the same situation.

Our group spent a lot of time in the water with other sperm whales in Dominica as well. Local researchers and whale watch operators have identified dozens of resident whales, and two local pods happened to be aggregating into social groups while we were there. During social gatherings, the whales let us get as close as we wanted to (we were careful of flukes thrashing up and down, of course — there was a lot of surface activity!). Still, we never tried to touch any of these whales because they are fundamentally wild animals, and lack of respect could easily lead to a response that might cause injury or death.

During social gatherings, sperm whales rub against each other and communicate non-stop by clicking, clanging and wheezing (like dolphins do). I observed that a good number of the juvenile males became sexually aroused when rubbing against each other. Photography conditions were fantastic during the beginning of each social gathering, but after ten minutes or so, the water around the cluster of whales was often filled with micro-bubbles and sloughed-off sperm whale skin, which looks like sheets of thin, black plastic. (...=

Published in

- Log in to post comments