Statistics show that more Americans dive in the US state of Florida than any other place on the planet, but when you consider what is on offer, it is hardly surprising. The state’s government has been instrumental in sinking some of the world’s largest (so-called) artificial reefs, but there are also freshwater pools, caves and caverns with a constant warm water temperature all year-round, which certainly appeals to winter divers.

Contributed by

There are great encounters with large critters like manatees. Of course, the farther you travel south towards the Florida Keys, the more the country is influenced by the might of the Gulf Stream. There is great ease of access down to the Sunshine State. More than anything else, Americans are able to experience almost the full range of Caribbean-style diving without leaving the country or needing a passport.

There are very good quality coral reefs (albeit a 20- to 30-minute ride offshore) with a huge wealth of marine life, and I can honestly testify to the fact that I can see more varieties of Caribbean reef fish here than at most other locations in the Caribbean. All well and good for American divers, but why should foreign divers opt for this particular diving destination?

Artificial reefs. Some of the largest artificial reefs in the world have been sunk off the eastern and western coasts of Florida (particularly along the eastern and southeastern flanks of the Florida Keys). The state tourism agency, Visit Florida, which is responsible for the promotion of the Keys, is so switched on that it has an annual advertising budget that surpasses that of most large multinational companies. Such is their power that it is no wonder tourists make their annual pilgrimage to a long string of sandbars connected by bridges, which are really only appreciated in Hollywood blockbuster movies.

This tourist board will do (almost) anything to get divers down, and that includes sinking a large number of derelict ships within the 36m (120ft) range at the confluence of the eddies, which are produced by the constant flow of the Gulf Stream. This nutrient- and plankton-rich current is so full of microscopic marine life that in hardly a blink of an eye, the ships sunk as diver attractions are soon covered in a patina of marine organisms as well as the ubiquitous reef fish that love those environments, including horse-eye jacks, trevally, barracuda, chromis, creole wrasse, hamlets, snapper, grunt and parrotfish.

Shipwrecks. Not only are there artificial reefs (old ship hulks sunk as tourist attractions), there are also the remnants of the Spanish treasure fleet, which foundered on the shallow shoals and sandbars around the Keys. These ships carried so much wealth back to Spain that although only 10 percent of their cargo ever reached the “Old World”, that 10 percent bankrolled the country for over 300 years. (If you have time in Key West, go and check out Mel Fisher’s share of what was brought up—whilst he was still alive—and what is still being brought up today from the Nuestra Señora de Atocha).

That of course leaves the other 90 percent of the Spanish treasure ships still to be found, many of which are recorded as coming to grief upon the shallow reefs of the Florida Keys.

There are also ships dating back to the American Civil War. As always, ships that get wrecked in shallow waters are not only salvaged extensively, they are always pounded incessantly by storms, which rumble up the coast from June to November every year. However, it is those ships sunk as diver attractions that are a “must see” for most divers, and I can honestly say that I agree with them!

Dry Tortugas

South of Key West at the very end of Highway 1, you can take a small seaplane or boat trip out to the Dry Tortugas, the very tip of the sandbars that created the Florida Keys. The snorkeling here around Fort Jefferson—a former Civil War prison—is excellent and seems so far away from the rather hectic road that connects the rest of the Keys.

The Florida Keys are roughly fish-hook shaped and are really an eons-old result of the massive outflow of water from the Mississippi River coupled with the permanent current of the Gulf Stream, combined with the might of the trade winds and the periodic, yet fairly predictable hurricanes and tropical storms that pile even more sand and coral debris onto the shores of the Florida Keys. Needless to say, virtually all of the diving undertaken is well offshore, and most of the smaller diving operators up and down the Keys will just not venture out the three or four miles to where the reefs and wrecks are, if the weather is in any way inclement.

There are those companies who will get you out there, and they will tailor the diving to the experience level of those in the group. This may exclude some divers for the safety of the whole group. In all cases, the diving is set to the lowest common denominator, with safety first and foremost at the top of the list. Decompression diving is discouraged (and indeed frowned upon) at any of the deeper wrecks, and dive guides will cajole you along to many of the best bits of reef or wreck to see, before you have to ascend to the obligatory safety stops on the mooring lines. That is not to say that they are wrong, but sometimes I would just like to stay a little bit longer.

Some of the diving done in the Keys have the potential to challenge technical divers; but with the great care taken in the sinking of the artificial reefs, the diving experience is the same as it can be for everyone concerned.

Key West

What better place to start than at the southernmost tip of the Continental United States, and coincidentally, on the largest of the ships sunk along the Keys? The Dry Tortugas to the south, where the amazing Fort Jefferson is located, has always been a favourite with divers and snorkellers, but all of this diving involves fairly lengthy boat rides.

General Hoyt S Vandenberg wreck. From Key West, the wreck of the General Hoyt S Vandenberg, once used as a film prop for a Hollywood epic is undoubtedly the star attraction. Sunk in 2010, this former troopship and missile tracker has two huge radar dishes on either side of the deck.

At 156m (520ft) long, it can take several dives to get your bearings and really appreciate the scale of the ship. You should expect some current, but the ship has several mooring buoys, and the super-safety-conscious dive leaders will make sure they get you back safely and in plenty of time.

Large pelagic schools of fish are the norm here, and there was even an unconfirmed but very confident sighting of a great white shark the week before I arrived! With its huge American flag constantly flying from its superstructure, the ship is becoming colonised at a rapid pace. Turtles, barracuda, scores of tuna and jacks surround the ship. Most divers will do a twin tank dive just to get a flavour of the amount of superstructure that is underwater.

Even in rainy, windswept conditions and relatively rough seas, I was kind of reminded of venturing out into Scapa Flow, but the ship lying underneath me was in waters very much clearer than in Scotland, so much warmer and being able to see huge vistas, is staggeringly superb with plenty of photo opportunities. Bob Holston and his wife Ceecie at Dive Key West are very much the driving force behind the sinking of this ship and its promotion, as it takes a lot of time and effort to get to Key West to do this particular shipwreck.

Marathon

Moving up the Keys in that wide sweep of mangrove swamps and sand cays, incredible bridges connect everything. Amidst the scene of many a Hollywood blockbuster are the delightful reefs around Marathon. There are more fish species recorded at these reefs than anywhere else in Florida; but again, these reefs are also offshore and do involve some lengthy boat rides. However, once you get out to the Looe Key National Marine Management Area, it is all worthwhile.

Looe Key National Marine Management Area. This triangular, shallow reef has a maximum depth of only 12m (40ft), and you can swim around the classic spur and groove reef structure hunting for little critters, as well as enjoy the larger fish such as tarpon and rainbow parrotfish. In the channels under the bridges, bull sharks are regularly seen. Whilst fishermen have known about them for a long time, it is only recently that local divers have become more interested as the currents push vast quantities of water through the connecting channels, giving rise to some amazing creature encounters.

Islamorada

Up in Islamorada, a few dive centres will run you out by Alligator Key where the wreck of the Eagle is located nearby. Located at the Postcard Inn, the Islamorada Dive Center’s boss, legendary spearfisherman Eric Billips has been taking divers out to the Eagle since it was sunk as an artificial reef in 1985.

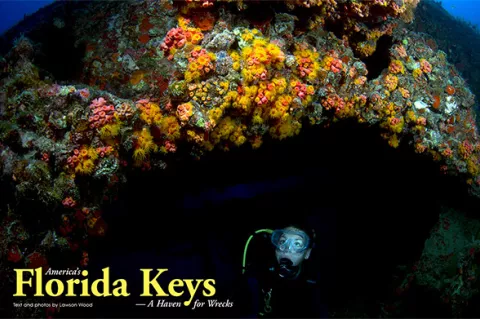

Eagle wreck. Laying on the starboard side with its bows pointing north in 33m (110ft), the Eagle is 86m (287ft) long and is fairly intact, apart from a large open section in front of the main wheelhouse area where the ship broke apart. Every surface of this wreck is covered in marine life many layers deep, with the most brilliant yellow cup corals vying for space with purple soft corals, brilliant red sponges, gorgeous queen angelfish, hamlets, chromis, wrasse and parrotfish.

As the shallowest part of the ship is at 20m (66ft), this is the perfect wreck to do two dives back to back to explore the entire length of the superstructure. I loved this wreck and cannot wait to get back! Eric has promised me a night dive on the wreck, which I suspect will have to be seen to be believed.

Alexander Barge wreck. Just to pique your interest is the nearby wreckage of the Alexander Barge, sunk in 1984 in 31m (103ft) of water. The sinking of this boat was really the start of the artificial reef programme. As you can imagine, this is also well encrusted in marine organisms, but is overall a much deeper dive; most divers would rather opt for the easier option on the Eagle as it is so close.

D&B Barge wreck. Also nearby is the D&B Barge wreck which is a natural shipwreck and completely covered in marine life. It is also a favourite spot for fishermen, so watch out for loose fishing lines.

Historic ships and anchors. Concentrating on the wrecks, there are a number of historic ships and anchors littering the shallow barrier reef; but for most divers, it is the wrecks sunk as dive attractions that get the eel’s share. Some of those anchors have become the focus for a dive, and names such as Pirate’s Anchor are really there only to pique your interest.

Key Largo

Key Largo in the north is considered the epicenter for the majority of divers. In fact, this long, stringy island gets customers travelling both south and north, giving divers a second chance to get where they want to go, with most people diving on both the wrecks and reefs. Subsequently, there are more dive centres located here than any other island in the Keys. However, there are also a lot of “tourist boats”, which take literally hundreds of families of snorkellers out to the reef. Whilst they may be a nuisance when you try to get your boat anchored up at a favoured dive site, they do not create any impact on the marine ecosystem at all.

John Pennekamp Coral Reef State National Marine Park. You cannot dive Key Largo and the great variety of wrecks there without first visiting the John Pennekamp Coral Reef State National Marine Park. Founded in 1960, the marine park is located in an area known to have the most extensive coral reefs in the United States and covers over 75 sq miles of ocean.

With over 500 species of fish recorded amongst the shallow reefs and protected mangrove forests, the shallow reef plateau has an average depth of only 8m (27ft), making it accessible for everyone. The first marine reserve in the United States is celebrated by a wonderful statue known as the “Christ of the Deep” or “Christ of the Abyss.” Located 10km (6miles) east-northeast of the South Cut on Key Largo, the statue is a replica of that created originally by Italian sculptor Guido Galletti for Edidi Cressi, who presented it to the Underwater Society of America. It has been underwater since 1961 and has been visited by literally thousands of divers and snorkellers.

This region of a large, horseshoe-shaped reef often has poor visibility, but nothing detracts from the statue or the condition of the reefs themselves.

Molasses Reef. Nearby Molasses Reef to the north is, however, well known for its excellent visibility underwater. Being so shallow, it gets lots of sunlight to brighten up even the dullest day. Molasses Reef has been undergoing something of a transformation lately, with newly seeded coral species being “planted” on the shallow reef platforms. Of those I viewed, most appear really healthy and vibrant.

City of Washington wreck. Further to the north on a reef known as Wreckage Reef, or The Elbow, are the remains of the City of Washington in only 6m (20ft) of water. This steel freighter ran aground in 1891 and was pounded mercilessly by annual storms until it was well broken up and encrusted in low hard corals, sea fans and literally thousands of Christmas tree worms.

Better known for its role in rescuing the survivors of the Maine, when the vessel blew up in mysterious circumstances in Havana Harbour, the Washington is a great shallow dive, in an area synonymous with clear water and good quality corals. There is a friendly resident moray eel, as well as hawksbill sea turtles.

Towanda wreck. Close by are the wooden remains and anchor chain from a ship thought to be the Towanda, which sunk during the American Civil War. A coral-encrusted anchor from the 17th or 18th century is also found in the vicinity.

Artificial reefs

Located also in the marine protected area are several other ships also sunk as part of the artificial reef programme: the Duane, Bibb and Spiegel Grove. Notwithstanding a large number of ships that have sunk naturally (or accidentally), these ships sunk specifically as dive attractions are a natural magnet for everything.

Benwood. Another shipwreck in the immediate vicinity is the Benwood. It was a casualty of a German submarine attack during WWII and was subsequently rammed accidentally by a “friendly” ship. Later, several bombs exploded in the vessel, amidships, and sent it to the bottom. Part of the superstructure was still above the surface, and it was then used for bombing practice before the bows were eventually blown apart, as the ship was becoming a navigational hazard. Lying from 7.6 to 16.7m (25-55ft) of water, Benwood is, as one can imagine, well broken up and very much a part of the extensive shallow coral reef platform.

Duane and Bibb. Near the Molasses light tower, the Duane and the Bibb were sunk deliberately on 27 November 1987 as dive attractions. Former US Coast Guard cutters, they are both 98m (327ft) long and were sunk in relatively deep water, over 30m (100ft) so that they would not become problems for navigators. Subsequently, these dives are regarded as deep wreck dives; and with the limited time underwater always a problem on these dives, that just means you would have to return several times to fully appreciate these wrecks.

Having only limited time to visit these wrecks due to the onset of bad weather, I was advised to dive the Duane out of all the three new wrecks. Not only does it have the best coral growth and fish life, Duane’s superstructure is more interesting and the crow’s nest comes to within 15m (50ft) of the surface, to allow you to start your safety stops, yet still be able to do some photography. Amazingly, Duane’s entire uppermost steelwork is literally covered in golden cup corals (Tubastrea coccinea), giving the ship's outline a golden, fuzzy appearance.

The Gulf Stream undoubtedly has a huge influence on these wrecks. Cccasionally, the unpredictable currents and eddies just rip along the shore here, making diving on them virtually impossible. Dive lights are always recommended on these dives, to allow you to penetrate further into the ships, but I am always quite happy to bimble about on the outside, enjoying the coral growth and the fish life surrounding them.

Spiegel Grove. Amazingly, when the Spiegel Grove was first sunk further north from the Benwood and Dixie Shoal, it ended up on its port side, making it a difficult if not interesting dive. However, a few years and several hurricanes later, Spiegel Grove was put back up on an even keel, making the ship even more remarkable.

Current, as always, can be a problem when one is so far out in the Gulf Stream, but the rewards are utterly amazing, and I have to say that these wrecks to the east of the islands in the Stream have to be on everyone’s diving list. I only visited them briefly, but I am determined to return and also dive them at night, as the colours, often hidden during the daylight hours, will all be revealed in their glory after dusk.

Best time to go

Diving is available all year-round. However, there are periodic storms from the southeast, which can strike the Florida Keys any time from June to November. The summer months yield the best visibility. Strong currents and eddies from the Gulf Stream can cause problems on the deeper wrecks. Due to the fact that the reefs and wrecks are all so far offshore, the sea conditions have to be near perfect before any dive boat will venture out into the Stream. Offshore storms along the eastern coast of Florida are always a problem, but for the most part, all of the reefs and wrecks are manageable.

Conditions and visibility

The inshore reefs along the Keys average around 15m (50ft), with greater visibility variable the further one travels offshore. The underwater topography undoubtedly has an influence on the visibility, as on two back-to-back dives at the Christ Statue and then the nearby City of Washington wreck, which was in shallower water, the difference was at least 15m (50ft) better on the shallow reef where the wreck is found. The sea temperature rarely drops below 22.2°C (72°F) in the winter months, and increases by 10° on average, depending on the strength of the Gulf Stream. ■

The author was supported by the Florida Keys Tourism Association and the Postcard Inn in Islamorada and dived with Dive Key West, Islamorada Dive Center, Rainbow Reef Dive Center and Pennekamp State Marine Park. Special thanks to Cecilia McCafferty, Eric Billups, Bob and Ceecie Holston, Jo Thomas, Carol Shaughnessy, Jodie Remick, Stacy Sheldon, Allison Ballester and DJ Wood.

Lawson Wood is a widely published underwater photographer and author of many dive guides and books. For more information, visit: www.lawsonwood.com.