Muck diving on Guam was little known by divers until a few years ago when local residents started posting images online from muck dives. Simon Pridmore and Steve Wolborsky tell the tale.

Contributed by

Twenty-five years ago, I opened a dive center in Guam called Professional Sports Divers. This was the first dedicated technical diving center in the Western Pacific, but we also taught people to dive and took fun divers out to see Guam’s reefs and wrecks.

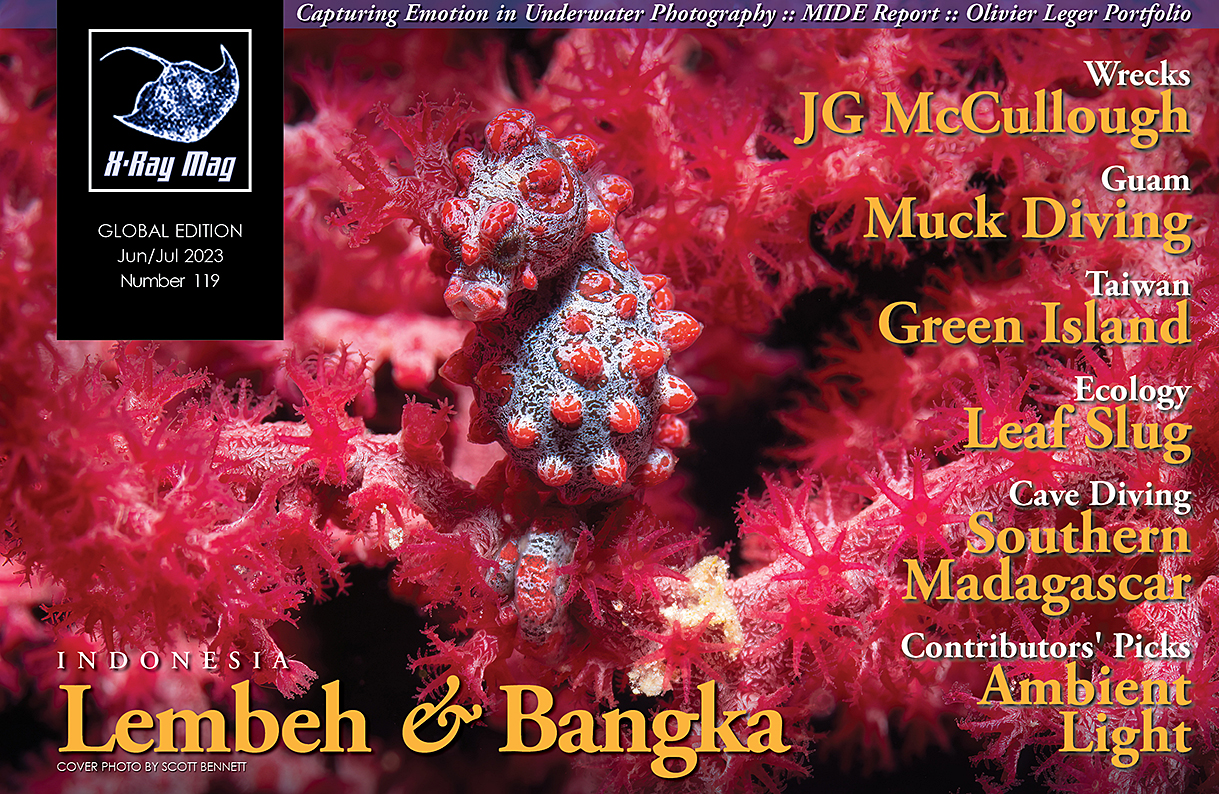

Around the year 2000, I came across the term “muck diving” on a trip to Papua New Guinea and did a couple of wonderful long dives looking for and finding—with the help of sharp-eyed guides—some rare, beautiful little creatures in unusual places, such as ugly patches of seabed where you would not usually take fun divers. I also saw a pygmy seahorse for the first time. It was a Bargibant’s seahorse, of course. At that time, it was the only one anybody had ever found.

On my return to Guam, I had a brief look around to see if similar creatures lived in Guam waters, but it was a fruitless quest, soon abandoned. After all, my main jobs were to run the business and teach people how to dive deep and penetrate shipwrecks safely, not spend hours looking for tiny things that might not even be there.

Then I left Guam in 2003, there was still no muck diving there and I never gave it another thought. Over the following 15 years or so, my wife Sofie and I dived all around our new home country of Indonesia, did hundreds of muck dives and saw some astonishing animals.

Then, a couple of years ago, I started seeing some amazing macro images being posted on Facebook by Guam residents Steve and MJ Wolborsky.

I messaged Steve:

“Where were these taken?” I asked. “Lembeh? Dumaguete?”

“This is Guam,” he told me.

I was absolutely stunned.

“Man!” I told him. “We were diving in the wrong places all those years ago.”

Then he told me where the pictures were taken and it turns out that we had been diving in all the right places, we just didn’t have the knowledge then to find these creatures nor the equipment to record them.

Steve and MJ have plenty of both. This is the tale of how they did it and these are their pictures.

I’ll let Steve take up the story…

Steve and MJ’s story

There are two particular sites where we have gained considerable experience and knowledge of Guam’s tiny underwater world—Piti Channel/Tunnels and Outhouse Beach.

Piti Channel/Tunnels

Near the southern edge of the Piti marine preserve area, the outline of Piti Channel is visible as a dark blue path snaking through beautiful scenery. The channel flows under a road via five tunnels and these tunnels have been the main object of our exploration.

We started with night dives in the otherwise barren sand channel on the ocean side of the site, which is less than 5m deep in most places, allowing for extended bottom times. It comes alive after dark with shrimp, crabs, eels, octopus, scorpionfish and leaf fish (Taenianotus triacanthus). While doing these initial dives, we noticed that the terrain approaching the tunnels became more mixed, with coral, several species of algae, and more sea life overall.

So, we started to investigate the tunnels more thoroughly, diving mostly during the day and occasionally at night. We developed a classification system, numbering the tunnels from 1 to 5 running east to west, with an ocean side and a shore side for each. This allowed us to quickly compare notes post-dive, e.g., “I saw that nudibranch in tunnel 3, east wall, 1/3 of the way in from the ocean side, and 1/4 of the way up the wall.” The tunnels are all about 4m wide and 4m high, save one that has significant sand berms undulating down its length.

Each tunnel seems to have a relatively unique ecosystem, with some species occurring only or predominantly in one tunnel. Other species are prevalent across the site. The tunnels are encrusted with brilliantly colored corals, coralline algae, plants and sponges (among other things like beer bottles, abandoned underwear, and snorkel gear). Our weather lets us dive most days, so, over time, we have documented seasonal and other time-based changes, as well as significant differences between day and night. To date, we and our dive buddies have identified 99 distinct species of sea slugs and nudibranchs there. This is also so far, the only place in Guam where we have seen harlequin shrimp (Hymenocera picta) and pom-pom or boxer crabs (Lybia tessellata). We have also seen far more leaf fish and robust ghost pipefish (Solenostomus cyanopterus) here than anywhere else.

Our journey of discovery reached an apex when, in July 2020, I noticed an Avrainvillea algae leaf in the sand on the ocean side of the channel itself. This leaf is the habitat for Costasiella species sap-sucking slugs (sacoglossans), popularly called “Shaun the Sheep” due to their resemblance to the eponymous character from the Wallace and Gromit children’s series. I investigated more in hope than expectation and, to my surprise, discovered a tiny Costasiella kuroshimae, my first Shaun on Guam. Since then, we have found multiple species at different sites.

The tunnels house octopus in a large range of sizes, but we’ve only seen one species so far, Octopus cyanea. The smaller individuals can be found inside abandoned beer bottles or skittering along the bottom of the tunnels, especially at night. The tunnels are also the only place we have found frogfish (Antennarius sp.) on Guam.

Outhouse Beach

Outhouse Beach sits on the northern arm of Guam’s Apra Harbor, on the Glass Breakwater. It is the go-to site for most local instructors since it has a lot of shallow areas with few obstacles and navigation is simple.

Then we started shooting macro there, we found few worthwhile subjects and thought of it just an OK backup site when the tunnels were not dive-able. Then, one day in early 2021, on a whim, rather than going east as usual, we headed west, and, to our delight, found many nudibranchs there that we had never seen before. Since then, for the past two-plus years, we have been diving Outhouse on average four to five times a week, finding and identifying sea slugs and nudibranchs. As I write, we are up to a total of 63 species. Some, like Hypselodoris infucata and Roboastra tentaculata, we have found nowhere else on Guam. Plus, we have found and identified at least four species of Costasiella slugs.

Outhouse also has a lot of other photo-worthy subjects. It is home to cephalopods like Octopus cyanea and the cuttlefish Sepia latimanus, as well as superpower crustaceans like the peacock mantis shrimp (Odontodactylus scyllarus). We have recently found numerous mouth-brooding cardinalfish such as Ostorhinchus luteus and many colonies of tiny skeleton shrimp (Caprella spp.), all no wider than a human hair and no longer than 3mm.

Putting Guam on the Macro Map

Local dive operators have never promoted the island as a destination for macro and muck diving, but that may change as we discover more potential sites. Inshore areas of Guam’s fringing reefs have great potential as a habitat for small creatures and serve as a nursery for juvenile fish and invertebrates. While the sites are perhaps not as robust in sheer quantity of subjects as their counterparts in the Philippines and Indonesia, they are quite viable and likely to yield many more surprises.

Our exploration continues. ■