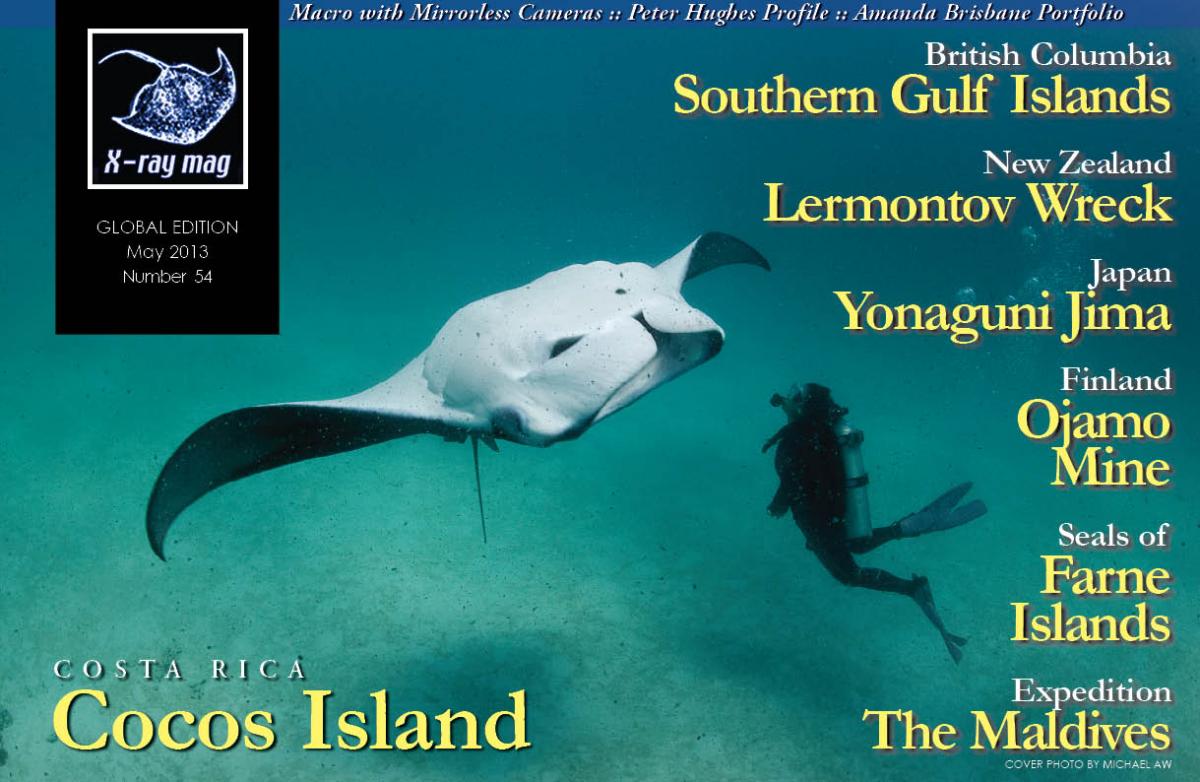

The Farne Islands are a small group of some 33 rocks and islets (depending on the state of the tide which has a rise and fall of over 6m or 20ft) located off the north Northumberland coast of England. At full tide, only 23 larger rocks and islands are visible, but all of those are eye catching. The entire group are a National Trust protected area and have numerous wildlife preserves, notably for their seabirds and seals.

Contributed by

Factfile

A founding member of the Marine Conservation Society, Lawson Wood has authored and co-authored over 45 books mainly on the underwater world.

He is the founder of the first Marine Reserve at St. Abbs and is the first person to be a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society and the British Institute of Professional Photographers solely for underwater photography.

There are numerous sightseeing boats and dive boats that run regular trips to the islands, but Paul Walker of Farne Discovery (www.farneislanddivers.co.uk) I personally feel, has the most experience and empathy for the seals and the most knowledge about the hidden shoals, wrecks, reefs and currents, which can play havoc for inexperienced divers and boat skippers.

Geologically, the islands are part of what is known as The Great Whin Sill, a 30m (100ft) thick seam of diamond hard dolorite that was formed in recent geological time. Its aspect is of columnar shape cut with numerous fissures, the most obvious being ‘The Stack’ off the southern edge of Farne Island, which is over 20m (66ft) high. Staple Island has three huge individual stacks called The Pinnacles. Most of the larger islands are now topped with peat and are very fertile with the droppings of the seabirds mixed with seaweeds.

Built in 1811 and 1826, there are two lighthouses on the islands—one on Farne Island and the other out on the Longstone. Now fully automated, the very early lighthouses first burned their rudimentary light to warn sailors of the treacherous reefs and shoals back in the 16th century.

Most people know of the Farne Islands from the outstanding heroism of Grace Darling and her father William Darling, one of the lighthouse keepers of the Longstone Lighthouse. On 7 September 1838, Grace Darling and her father rowed out to the shipwrecked Forfarshire and managed to rescue nine seamen in absolutely atrocious sea conditions. This act of selfless heroism attracted massive media attention and made Grace Darling a national heroine.

The Farne Islands were first inhabited by St.Aiden in 635AD before he became the Bishop of Lindisfarne. St.Cuthbert followed in his Holy footsteps and settled on the islands in 676AD where he built a ‘cell’ for himself, a well for fresh water and rooms or ‘hospitium’ for other visiting monks.

In ancient legend, St.Cuthbert drove out all the evil demons and spirits from the inner islands, yet their strange wails and screams could still be heard on the farthest rocks and were thought to be the spirits of drowned sailors; now it is more generally accepted as the sounds from the huge colony of grey seals.

St.Cuthbert was also the first person to officially protect wild birds and laid down the rules for the safety of the eider duck population, which was so vital for the collection of eiderdown, still known worldwide for its thermal properties.

Seals, or ‘celys’ as they were first known, were actively hunted by the monks as a high protein food source as well as providing oil for their lamps. Seals also provided the monks with a very profitable income—that and the salvage of shipwrecks of course! The monks also farmed, raised cattle, fished, collected seabirds’ eggs, and peat for their fires and kept one island reserved for the burial of lost sailors who had drowned and washed up on the islands’ shores.

The name Farne is a derivative of the ancient Celtic name Ferann, which roughly translates as land. I imagine that this group of large rocks was the first point of contact that raiders or settlers from Europe first saw of this beautiful low lying coastline. Individual names to the rocks date back to the sixth and seventh centuries and have remained almost unchanged to this day with names such as Swedman, Wamses, Knavestone, Wedums, Crumstone, Glororum Shad, Brada and Callers, to name but a few of these evocative sites. Some are more known for the massive colonies of terns, eider ducks, gulls and puffins, whilst others have a shifting population of itinerant grey seals.

These seal colonies are entirely dependent on the weather and height of the tide, as they like to bask in the sun on flat rocky outcrops that have direct access to deep water, directly off the shore. Sheltered locations and snug little bays are also favoured by the seals, and with a resident population of over 4,000 grey seals, there are plenty of opportunities for everyone to experience the thrill of a lifetime.

On nearby Holy Island or Lindisfarne, there are two more massive colonies containing another 5,000 grey seals. Over 1,600 seal pups were born in the 2012 season. While the mortality rate in the first year alone is very high at over 50 percent, the number still puts a tremendous strain on the population’s food source, resulting in large numbers of seals migrating to other parts of the United Kingdom.

Tagged individuals from Scotland have been found as far away as the Norfolk coast of England and the Baltic Sea. One particular individual was recorded as moving from the Moral Firth in northern Scotland to the Farne Islands, back up north to the Faroe Islands on the way to Iceland and southwest again to Ireland before the transmitter’s battery failed!

The grey seal

Known as phoque gris by the French and foca gris by the Spanish, the grey seal (Halich-oerus grypus, meaning “hooked-nosed sea pig”) is the most common seal found around British coastal waters—in fact, much more common than the common seal (Phoca vitulina).

The grey seal is a true seal—the only one classified in the genus Halichoerus—and is the largest carnivore recorded in British waters. It is found on both sides of the Atlantic and is also known as the Atlantic gray seal or horsehead seal.

It is one of the largest seals with bulls reaching 2.5 to 3.3m (8.2 to 11ft) long and weighing 170 to 400kg (370 to 880lb). The females or cows are much smaller, typically 1.6 to 2.0m (5.2 to 6.6ft) long and 100 to 190kg (220 to 420lb) in weight. The males have a straight head profile—a classic arched ‘Roman’ nose with large wide-set nostrils—and few spots on the body, which is generally darker than the females. They often have many scars around their necks earned from either protecting their harem or gaining superiority in a group. The females are generally a silver grey colour with light brown patches.

Diving down as deep as 60m (200ft), seals require an estimated 5kg (11lb) of food each day, but the females never feed during the breeding season, until their young pups have weaned. They feed on a wide variety of fish including most cod species, salmon and sea trout, flatfish, herring and sandeels.

Being opportunistic feeders, when fish are in short supply, they will eat almost anything, including crab and lobster, octopus and squid. There are huge aggregations of sandeels to be found around the Farne Islands in the spring months, and this massive natural resource is also very important to the colonies of puffins and other seabirds found on the ancient rookeries on the islands.

Pups are born from September to November from Canada down as far as the U.S. state of Virginia and from November through February in the western Atlantic. It is widely understood that the rising seal populations in the Cape Cod area of the U.S. state of Massachusetts were the reason that great white sharks started to be seen so frequently.

Protected under the Conservation of Seals Act of 1970, no hunting is allowed of the seals, but the rising numbers are causing increasing alarm to inshore fishermen who are complaining about dwindling fish stocks and are urging governments to take a fresh stance on the numbers and allow for culling to take place. Seals are allowed to be hunted legally in Sweden and Finland.

The largest colonies in the eastern Atlantic are found in North Rhona off the Hebrides in Scotland, and approximately 12 per cent of the world’s population is found in the Farne Islands. Other large colonies on the east coast include the Isle of May in the Forth estuary of Scotland and Donna Nook in Lincolnshire.

The pups are covered in long, soft, silky cream hair, and although they are quite small when first born, they rapidly put on weight, suckling their mothers five to six times each day for the first three weeks. This fat rich milk ensures the rapid growth rate of the pups, and the mother will lose a quarter of her body weight during this period. Within a month, the pups have tripled or quadrupled their weight, have replaced their sleek hair with the dense, waterproof, adult seal skin and are abandoned by their mothers to fend for themselves.

The females soon become fertile after weaning the pups and may mate with a number of different bulls. Pregnancy lasts for 11.5 months, with the fertilised embryo remaining unattached for the first 3.5 months. This delayed implantation is common in a number of aquatic species, resulting in seal pups all being born around the same time each year.

Seals can grow quite old, with records held for males over 35 years and females, less so, at 25 years. As usual, there are always exceptions to every rule, with one old female in the Shetland Islands reaching 46 years of age!

Normally, females give birth to only one pup and are known to abort additional fetuses. However, it was recorded on the Farne Islands in November 2012 that twins were born for the first time known to scientists.

As grey seals are at the top of the food chain in British waters, they are also susceptible to the accumulation of pollutants and heavy metals such as PCB’s (polychlorinated biphenyls). Females feeding on polluted fish may fail to breed resulting in hindering the recovery of some populations that have been reduced by disease.

Diving with the seals

Paul Walker of Farne Discovery has an empathy with the seals and great knowledge of their habits, habitats and movements. He is able to find the best sheltered conditions for great underwater wild animal interactions with these massive sea mammals. Depending on the rising and falling tide as well as current conditions, Walker will lead a small group of divers from his Rib Farne Discovery to the best locations for two dives.

Seals are everywhere. There are often literally hundreds of seals in the water, all of them looking at you on the bright orange boat (have you ever had that feeling of being watched? Well, multiply that a hundredfold). The younger yearlings and sub-adults are the most curious, often coming right up to the side of the boat before you even get in the water.

However, once in the water and approaching the first seals on the surface, they are quite skittish and will quickly disappear beneath the waves and vanish into the kelp covered canyons. Swimming slowly, it pays just to stay still mid-water or crouch on the seabed and wait for the seals’ curiosity to overtake them. They just cannot help themselves and soon come right up to you and seemingly pose for the camera.

As seals can slow their heartbeat down whilst underwater, they can stay submerged for around 15 minutes and often appear to be asleep on the seabed or amidst the shallow kelp. This is just a ruse to ambush you! Whilst you are ‘sneaking’ up to photograph the resting seal, another seal has circled behind you and may start to tug at your fins, or even try and pull your dive hood off! As soon as you turn around to confront your attacker, it scoots off or just stays in mid-water acting all innocent.

Turning around to photograph your first subject, you discover that it has disappeared in a cloud of bubbles, only to have your attacker have another fun go from behind at your expense. They clearly have enormous fun doing this, and it gets quite infectious, with the divers enjoying the experience just as much as the seals. These encounters are not to be missed, and the Farne Islands are one of the best and safest locations for in-water wild animal encounters with one of the sleekest hunters in the coastal waters.

Conservation status

The grey seal is classified as Least Concern (LC) on the IUCN Red List. They are protected in Europe under Annex II and V of the EC Habitats Directive and Appendix III of the Bern Convention. In Britain, the grey seal is protected under the Conservation of Seals Act 1970 (closed season from September 1 until December 31) and listed under Schedule 3 of the Conservation Regulations (1994). In Scotland, it is still legal—within reason—to shoot seals that are damaging fish nets as long as it is outside the closed (breeding) season, although there is provision in the Act to completely protect them. ■

Published in

- Log in to post comments