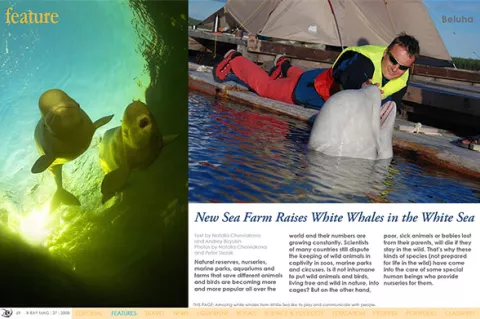

New Sea Farm Raises White Whales in the White Sea.

Contributed by

In 2006, marine biologists from St Petersburg’s department of Utrishsky Dolphins’ Aquarium decided to initiate a scientific project to build a natural farm, or nursery, for the breeding of white whales—or beluhas, as they are called in Russia—on the White Sea. One of the main aims of the project was to decrease the number of white whales caught from the wild and to exchange them with animals born in natural sea nurseries like this one.

By the way, only two countries—Japan and Russia—continue to catch white whales. It takes a lot of experience and a high level of professional skill.

The second reason for building this new natural aquarium was to make a vacation place, or a spa, for polar cetacians, to bring white whales here from big cities and provide a temporary place for rehabilitaing them in a natural environment of the White Sea waters where they could regain strength, immunity and well-being.

Is it not inhumane to put wild animals and birds, living free and wild in nature, into cages? But on the other hand, poor, sick animals or babies lost from their parents, will die if they stay in the wild. That’s why these kinds of species (not prepared for life in the wild) have come into the care of some special human beings who provide nurseries for them.

This new generation of natural dolphin aquariums are not built to be circuses, but to provide a new approach to direct communication between humans and sea mammals.

At the end of January 2007, two young white whale males, named Filya and Semen, came to the White Sea as the first residents of the new natural aquarium. In the move, they came back to their home waters, albeit in an open-water cage, near a local dive center called the Polar Circle.

Six years ago, these two males (then aged four years old) were caught from this same White Sea area. They were taken to an aquarium in St Petersburg and trained to give performances on tours to Moscow, Egypt and Saudi Arabia. During this time, they were in very good and constant contact with people.

It was lucky that both of these dolphins were well-adapted to the human beings in their new home, which made for good contact with scientists, biologists and divers.

The white whales, or beluhas, played very well with everyone who came to the open-water cage. With swimmers, they were happy to take each for a spin, and nibbled feet and hands in a very friendly way. But divers made the whales a bit afraid. For a long time, the beluhas preferred to take just a quick look at the bubbling persons and then stayed well out of the way.

The whales enjoy freedivers who come to the dive center. One women was free diving with a monofin. The whales became very happy, perhaps thinking that some of these intelligent beings with arms can live in the water like they do. The four-meter-long whales stayed close with this free diving woman the whole time she was in the water.

A few months later in the summer, the whales started to take interest in scuba divers. They would approach divers who were cleaning the cage and tried to take some of the cleaning tools. They seemed to have stopped worrying about the bubbles coming from the divers’ air tanks.

One of the divers described the experience: “It was a sunny day in September. I was standing close to the open-water cage with the beluhas and was preparing to dive in. Just in front of me, a huge white dorsal ridge appeared and slowly went back below the surface of the water. I took a camera and went underwater. In the same moment, Semen bumped his wide forehead into me with a smile in his huge beluha mouth. And his friend, Filya, was trying to taste my strobe.

Having made contact, I had become to the white whales a guest, and they started to play with me. I took pictures of the cheerful animals who looked to be really happy here in the natural dolphin aquarium on the Polar Circle of the White Sea. I used up my memory card and the air in my tank very quickly, but didn’t rush out of the water because I felt so lucky to see and be so close with these friendly animals.”

Special thanks to the Arctic Circle Dive Center staff for the great experience diving with white whales.

FACTS ABOUT BELUHAS

Beluhas (Delphinapterus leucas), otherwise known as white whales, are a threatened species. Found only in the northern hemisphere, beluha whales live commonly in the coastal waters of the Arctic Ocean. They can also be found in subarctic waters. When the sea freezes over, Arctic beluhas migrate southward in large herds. Sometimes they get trapped by Arctic ice and die, becoming prey for polar bears, killer whales, and for the indigenous people of the Arctic.

Because they have been over-hunted by commercial fisheries, some beluha populations, such as those in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, have nearly collapsed. They were hunted for centuries for their meat, blubber and skins used in products such as soap, lubricants, margarine, fertilizer, and shoes as well as fodder for domestic animals. Currently, 3,000 belugas are still taken each year.

Recovery has been hindered by harbour construction, river diversion and chemical pollution, which affects beluga fertility in some areas. The current estimated population is around 50,000-70,000 animals.

Characteristics

Beluha whales have an unusual colour that makes them stand out from all other whales. Their calves are grey or brown when they are born, a colour which fades to white when they reach five years old and become sexually mature. Before the summer moult, their skins take on a yellowish hue. Beluhas rub themselves along the sand or gravel of the seabed when their skins begin to moult.

As whales go, beluhas are small, ranging from 13 to 20 feet (4-6.1m) in length and can reach a weight of 2,000 to 3,000 pounds (907-1,361kg).

Their foreheads are round, and they have no dorsal fin. They are unique among whales in that they have flexible necks, which enable them to turn their heads in all directions. The soft and flexible blubber around the head gives the white whale the ability to easily change its facial expressions.

Behaviour

In general, beluhas live for 35-50 years in the wild and move together in pods or small groups. Mothers give birth to one calf every 2-3 years with a gestation period of a year. The mothers have close relationships with their calves.

Being quite social and very vocal animals, beluhas employ a diversified language of clicks, clangs and whistles. They can also imitate a variety of other sounds. The beluha is sometimes called the Sea Canary because of its high-pitched sounds. Beluhas have an advanced echolocation system. They can produce broad-band pulses in a narrow beam, which are aimed from their melon, their bulbous foreheads.

Feeding

Cousins to the narwhale, or tusked “unicorn” whale, beluhas feed on fish (such as herring, salmon and cod), crustaceans, worms and other invertebrates such as octopus, squid, crab, and snails. It is thought that echolocation aids in their search for food and that they used a sucking motion to pull prey into their mouths aided by the flexibility of their lips, a characteristic shared only by one other creature, the Irrawaddy dolphin. A beluga whale has been observed diving underwater for 20 minutes to a depth of 647m during feeding. ■

SOURCE: marinebio.org, wikipedia.com,

nationalgeographic.com