For us survivors of the Perestroika, there are still some nice things we recall from the nostalgic Soviet past—one of these being, of course, the endless Cousteau series, run and rerun so many times on black-and-white television. The skinny Frenchman, with the (supposedly) red beanie, introduced an entire generation (or two) to the mysterious underwater world, full of beauties and beasts. But getting there was something beyond any of our dreams—the gap was just too deep.

Contributed by

Even the terms “scuba” and “diving” had never been mentioned in the Russian voiceovers for the series, as these terms were adopted later in the ‘90s, after the sudden death of both the USSR and of Cousteau. Yes, he is said to have visited the Soviet Union once. Reportedly, his Zodiac ended up being hijacked somewhere in the Volga Delta.

Well, that’s water under the bridge now. Today’s Russian diver is a well-known character, sometimes controversial. But let’s leave the controversy aside for the moment, as it may be worth a separate article in itself, with international (albeit anonymous) testimonials. The subject of this essay is focused on two simple questions—where and how do Russians dive when not traveling abroad; and how far are foreigners allowed to go with their Russian dive buddies? Let’s talk about the destinations, seasons and bodies of water, how to get there and what’s the big deal about them—busting some myths along the way. And let’s start with a list of the top five.

1. Ice

The primitive understanding of Russia is that it is “oh soooo big and soooo cold.” Well, it is a huge chunk of Eurasia, stretched over 11 time zones, more than twice the size of the continental United States, though there are no warm seas around it. Manhattan lies farther south than the southernmost tip of Russia. St. Petersburg is farther north than the Alaska Panhandle, and Moscow is farther north than Edmonton in Alberta, Canada. Sochi, a popular resort area on the Black Sea coast, is as far north as Toronto, and only suited for the Winter Olympics. This means that there is almost no warm coastal strip, rather, the contrary. And, logically, the Russians manage with what they have, and in so doing, have developed the most advanced ice diving protocols.

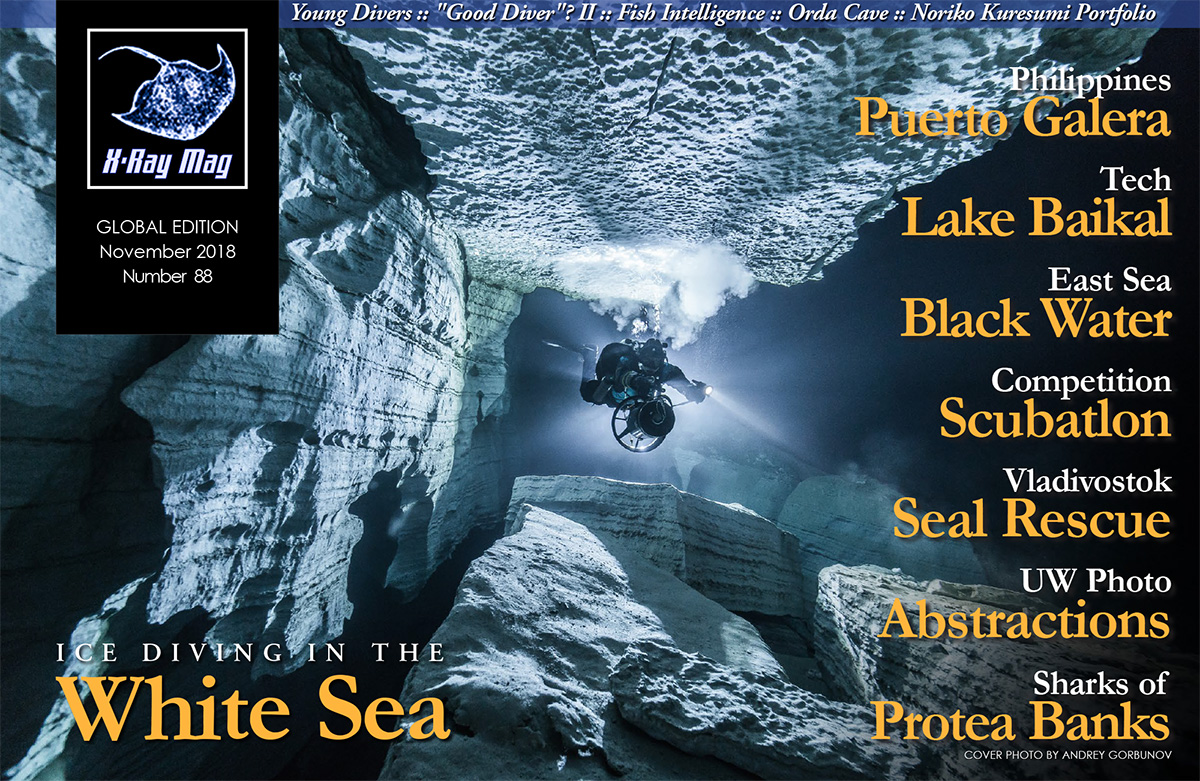

There are two areas where this extreme and elite kind of diving makes its home. The first is the White Sea in the northwestern region of the European side of the country. With the sea firmly frozen from November to March, compact dive teams ride snowmobiles towing equipment across the ice to quite a variety of nice spots. Triangular holes are bored in the ice, becoming portals to the upside-down universe underneath. The absolute highlight of this area is the multi-coloured, sun-lit ice boulders in the so-called Biofilters Bay, which can only be seen from below.

The second location for ice diving is Lake Baikal, the deepest freshwater body on the planet, containing more water than all the Great Lakes in North America put together. Freezing over in January, the ice grows one meter thick by March. The mode of transport invented and implemented by the local dive center is a jeep convoy slowly traveling on the ice from spot to spot. Diving holes are carved out of the ice with a chainsaw and then reused àpres dive, for the ultimate refreshing plunge after warming-up in the mobile sled-mounted saunas. Unexpected bonus features include ice skating on an endless pitch and watching the ice crack at night.

2. Dive clubs

In the big picture, the Russian dive market is in no way shaped by the regular old-school incorporated tour operators but rather by dive clubs. This type of dive club comprises a group of active divers led by a charismatic person, the so-called dive leader who plays the instructor, the retailer and the tour manager, all-in-one. These dive leaders are the crème de la crème of the dive scene—it’s them who go shopping for group trips at international expos, with a budget-backed wish list from their fellow divers.

A typical dive club has a couple dozen active members and makes four to five dive trips a year, aside from diving local bodies of water and house reefs. A fact worth mentioning is that this dive club format is customary not just in Russia but also in the adjacent ex-USSR countries, including Belarus, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and the Baltics, where many Russian-speaking divers live.

3. Wrecks

Artificial wrecks, or wrecks-to-reefs, are not so prevalent in Russian waters, though numerous commercial and marine vessels await scuttling in hidden coves, as clearly evidenced by Google satellite photos. So, shipwrecks are limited to those that are casualties of war and extreme weather. Well, a local dive club did try to scuttle a decommissioned trolleybus in a nearby pond, but they were caught in action and fined by the police.

The Baltic Sea preserves sunken vessels quite well due to low salinity. It is a seemingly bottomless graveyard for artifacts not only from both World Wars but also from earlier eras, including wooden sailing ships loaded with champagne. With new sectors being legally opened for exploration, advanced scanning techniques provide new discoveries every year—mostly U-boats lost in action and missing ever since. It is indeed cold and dark and muddy down there, and this kind of exploration is only possible via expedition with special permits. Nevertheless, for wreck addicts, it’s worth the effort. There are some even deeper and spooky wrecks of the same technical type to explore in the Black Sea; most of them imply operation from Crimea.

There are some diveable cold-water wrecks with some exploration potential in the Barents Sea, in the far northwest of Russia, a few miles from the Norwegian border. In Liinakhamari, there has been a quick development of dive centers with dive boats. Wrecks are not the only feature here, as the Barents Sea is full of vibrant Arctic flora and fauna.

There are a variety of wrecks in the much warmer waters around Vladivostok in the Far East, in southeastern corner of Russia bordering North Korea by land and Japan by sea. Military wrecks in the Kuril Islands in the Pacific remain unexplored since WWII.

4. Big creatures

The Soviet Union ceased industrial whaling 30 years ago. Today, only a minimal exception to the ban is made for the native folks of Chukotka in keeping with their traditional hunting rituals. Humpbacks are sighted along the coast and bays of Kamchatka and the Kuril Islands, along with killer whales, porpoises and other cetaceans. Recent exploration trips undertaken by Mike Korostelev, an internationally renowned wildlife photographer who produced underwater shots of salmon-hunting brown bears on Kamchatka, give proof of close encounters with bowheads in the nearly inaccessible Shantar Archipelago in the Sea of Okhotsk. These areas can only be accessed via expedition, with no guarantee of a sighting, but this only means there are still things yet to explore.

In English, the white whale is confusingly called a beluga, which is the proper Russian name for the big Caspian sturgeon. Beluga whales are abundant in the White Sea, and a dive center has been recently set up on the infamous Solovki Islands, focusing only on beluga watching.

Perhaps the most exclusive experience a diver can have in the far-eastern area of Vladivostok is an encounter with the giant octopus, Enteroctopus dofleini, in the coastal waters of the East Sea (Sea of Japan), which, incidentally, is called the Whale Sea by the Chinese.

5. Training agencies

Both the big ones and the young but dynamic ones have found their way to the promising Russian market. The big picture here differs from what is known about the American market. No reliable numbers are available from the head offices and representatives. To fill this lack of information, Ultimate Depth attempted a survey of 528-plus registered dive instructors and those attending the Moscow Dive Show 2017. These data are only a snapshot but may give an idea. Yes, PADI is clearly the king of the hill, with roughly two-thirds of all certifications. A quarter of certifications (trended to shrink) are from CMAS, which is almost invisible in the United States, while the acting president of CMAS is the Russian, Anna Arzhanova. The real surprise is the agency in second place: NDL, the National Dive League—a Russian training and certification agency established in the early 2000s—which is gaining more and more ground.

Of course, all international dive certificates are recognised by Russian dive centers—though a check dive to prove one’s skills is best not to avoid, especially in cold water.

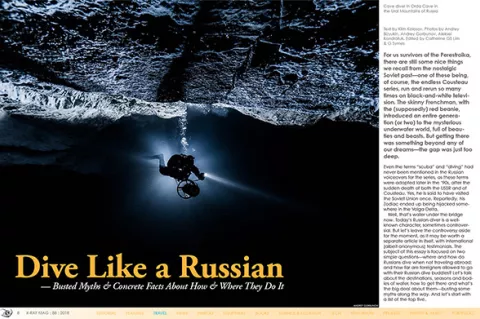

6. Caves

Caves are perhaps Russia’s least known area of exploration—the unsung hero of the Russian dive scene. One brand name has made it to the very top of international ratings: the Orda cave, or, in full, Ordinskaya Peschera, in the region of Perm, in the middle of the Ural Mountains. Orda is on record as the biggest of its kind, with clear ice-cold water and miles of well-mapped halls. Among the high-profile guests of Orda Cave are cave diving gurus Martin Farr, Lamar Hires, Jill Heinerth and deep diving record-holder Pascal Bernabé.

7. Tech

Beside cave diving and wreck diving, there are nice playgrounds for technical diving in its purest form: going as deep as it gets. The Russian speciality is freshwater technical diving. And it’s, well, cold of course.

Lake Baikal has already been mentioned for ice diving, but it also has a strong tradition for technical cold-water diving. Tatiana Oparina recently set a deep and cold record with a 160m open-circuit solo dive.

Another highlight is the Lower Blue Lake in the Northern Caucasus, 279m deep, with a newly opened dive center for advanced technical diving.

Do Russian technical divers use rebreathers? Yes, and furthermore, they improve and sophisticate them. Just to mention one, Sergei Baykov built a fully functional sidemount rebreather with original titanium parts. A couple of years ago, Baykov, together with two other technical divers, ventured a 10km eight-hour rebreather dive along the coast of Dahab; it may be yet another unregistered world record.

8. Liveaboards

For liveaboard operations, Russian slang has adopted the term “safari,” which has been in use without any problems until Aggressor Fleet opened a branch of on-shore safari lodgings, returning the term to its original meaning.

Regular liveaboard trips are run on Lake Baikal between early May and late December. The vessels chartered by local dive operators are safe but may be compromised in comfort, which, in turn, is part of the experience. Underwater landscapes are dominated by tubular sponges and rock formations.

There is an emerging liveaboard operation based in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, which covers Kamchatka, the Kuril Islands and the Commander Islands. The safari season is extremely short here, from mid-July to mid-September, but the experience is high in exploratory value and absolutely pays off, including uninhabited volcanic islands, kelp forests, whale watching, bird colonies and intense macro life.

9. Moscow Dive Show

The signature event of any mature market is its own industry expo, and there is one in the Russian diving scene. The annual Moscow Dive Show was launched from scratch after the sudden discontinuation of the good old Golden Dolphin dive expo. It will kick-off its 4th edition on 31 January 2019, just a week after the Boot Show in Düsseldorf. The dates were picked on purpose in order to help facilitate participation by overseas exhibitors who have already made their way to Europe, as Moscow is just 3.5 hours from Düsseldorf, with several daily flights available.

The original concept of the Moscow Dive Show was to bring underwater folks together and get them to interact in order to foster new momentum in the industry. Now the underwater part of the show is more or less established, and the expo is expanding towards other water sports and recreation. Board riding of every kind, yachting by sail or motor, water tourism, kayaking and every sort of beach and seaside recreation finds its place at the show. Düsselfdorf’s Boot Show was a great example to follow.

In brief, the facts and figures of the 2018 event were quite impressive: 200+ exhibitors from 20+ countries covering 10,000 sqm in three halls, and 20,000 visitors in four days, including 1,000+ dive pros, and a long list of side events and presentations. Evidence of the quality of the Moscow Dive Show is the fact that governmental tourism authorities from several important destinations use the expo to display their wares. In addition to these numerous national tourism boards, there are major distributors, manufacturers, retailers, training and certification agencies, dive resorts and liveaboard operations. Notably growing is the Russian fraction of the manufacturing sector.

The show is seen as the ultimate place where dive leaders all over Russia and adjacent ex-USSR countries can come to shop dive travel to fill their tour calendars. In terms of retail sales, it is a huge sales opportunity with one-off specials and a presentation stage for new products and new approaches. For instance, the old-school shops are being more and more replaced with online e-commerce, and this trend is fully reflected in the exhibitors list.

10. Seasons

Okay, admittedly, Russia is cold and big. Standing up to its name, the Moscow Dive Show is scheduled for early February (31 Jan - 3 Feb 2019) just to symbolically mark the zero-degree point on the calendar. During the dive show, or immediately after, ice diving can be tried just outside Moscow. From February to April, it is ice jeep safari season on Lake Baikal. December to March is ice diving time on the White Sea. In May, liveaboard trips commence on Lake Baikal and last until December. From June to September, the Barents Sea is at its best at Liinakhamari. July, August and early September is optimal for liveaboard trips in Kamchatka and beyond. August to September is the peak season in the Far East around Vladivostok on the East Sea. And Orda Cave is accessible all year round. There’s enough diving here to fill the calendar for a full year.

Klim Kolosov is the editor of the premier Russian dive magazine, Ultimate Depth.