The waters of the Eyjafjordur Fjord were still and calm. There was a sharp crispness to the air and snow covered the hills lining the shore. Except for the gentle lapping of water against the sides of our inflatable dive boat, the world around us was silent. To the north we could see heavy gray clouds hanging low to the horizon, the first signs of an approaching storm undoubtedly born in the Arctic wilderness just a few miles away. In a few short hours, the weather would turn bad and diving would become impossible. For now, all was calm and we were focused on preparations for an underwater adventure to an alien world.

Contributed by

In 1997, divers Erlendur Bogason and his friend Árni Halldósson discovered an amazing hydrothermal vent in the dark waters off the shores of Hjalteyri, a small fishing village located near the town of Akureyri. Strýtan, as this location has been named, is a towering chimney-like geological formation rising to over 200ft (230m) from the ocean floor to nearly 50ft (15m) below the surface.

Hydrothermal vents have been discovered in many places throughout the world, usually along continental rift zones, but they are generally located many thousands of feet deep. Currently, Strýtan is the shallowest known vent in the world and the only place where scuba divers can actually dive on an active hydrothermal vent. A white smoker, Strýtan is a set of chimneys that continually emit very hot water 167˚F (75˚C) at an estimated rate of 26 gallons (100 liters) per second.

These geological formations are formed by smectite, a white clay material that mixes with other crustal elements and minerals as it circulates through the oceanic crust under very high pressure and temperature. When this material mixes with the cold ocean water after emerging from the ground, it coagulates, hardens and forms the chimney. Strýtan started forming at the end of last ice age 10,000 years ago.

At Strýtan, divers can explore these towering formations and will marvel at the marine life that abounds in these waters.

Diving

Our dive began with a routine back roll into the teeth-chattering 34˚F (1˚C) water. Instantly, our eyes adjusted to the dim light of the greenish-black water. Peering down through 50ft (15m) visibility and searching for something to orient ourselves, we focused first on the down line.

Bogason, who operates the nearby Strýtan Divecenter, has installed a mooring buoy to ensure the protection of this delicate environment and to help divers find their way to the site. Descending into the waters of the fjord, our eyes opened wide as the first glimpse of the chimney came into view.

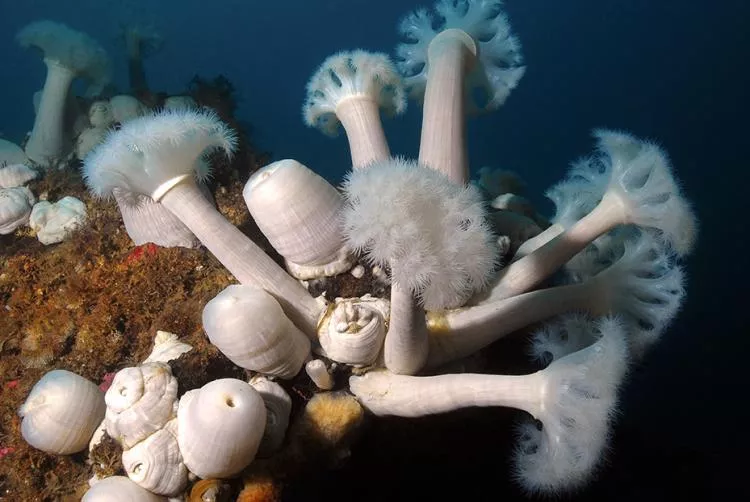

At first, Strýtan appears as a tall, narrow spire—rocky, covered with multi-colored plumose anemones, but otherwise somewhat uninteresting... until you get close.

After just a few minutes, we became aware of hazy, “out of focus” water—the telltale sign of hot fresh water mixing with cold salt water. These haloclines and thermoclines were easy to spot and were the best evidence of the rushing geothermal water flowing into the fjord. Scientists studying this phenomenon estimate that the water emerging from the cone is about 1,100 years old.

Normally, divers in very cold water never remove their gloves—but at Strýtan, things are a bit different! Divers here can carefully remove their gloves and warm their hands in the hot water flowing out from the cone—a unique method of hand warming on a cold-water dive!

Marine life and protected areas

In addition to geological marvels, Strýtan is home to a wide array of interesting marine life. Macro enthusiasts will spot colorful Flabellina sp. nudibranchs, along with crustaceans, sponges, starfish and anemones. Swirling around the chimneys are schools of cod and pollock. Sharp-eyed divers will also encounter starry rays, the curious lumpsucker fish and the ferocious looking wolffish.

Strýtan is the first protected underwater area in Iceland, gaining this status in 2001. This unique location has received worldwide scientific attention as well as being filmed by Bogason for National Geographic. Despite the rugged appearance, it is actually a fragile environment. Careless divers who don’t pay attention to proper buoyancy can quickly damage rock formations that have taken thousands of years to form. Visitors are strongly advised to be careful and respectful.

Nearby in the same waters are other dive sites worth visiting.

Arnarnesstrýtur, sometimes referred to as “Little Strýtan”, is a cluster of smaller hydrothermal vent cones covering an area 1,312 feet (400m) by 3,281 feet (1,000m) with an amazing variety of marine life. Arnarnesstrýtur was protected in 2007 and became the second protected underwater area in Iceland.

The French Gardens is a sublimely beautiful, though rarely visited site consisting of additional cones and vents.

Additional adventures

Diving in Northern Iceland is a unique adventure. Here, divers can experience the wonders of Earth’s geological forces by visiting the underwater hydrothermal vents or by diving in Nesgla, a crack or fissure in the Earth’s crust formed through tectonic activity and flooded with water of unbelievable clarity. Opportunities also exist to dive with spawning cod fish in early April, and to experience diving sea birds off Grimsey Island, a small island north of Iceland and located right on the Arctic Circle. In the harbor near Akureyri, the wreck of the Standard lies in shallow water. A German bark, Standard was built in 1874, sunk in 1917 and discovered in 1997.

Two hours outside of Reykjavik is Thingvallavatn Lake, home to a ruptured landscape torn apart by geological forces. In and around the lake are many fissures and tectonic cracks, many of them filled with glacial melt water from Iceland’s second largest glacier, Langjokull.

This water, filtered for 50 years through miles and miles of lava rock, emerges here as clear and clean as possible. It is here that divers can visit Silfra, one of these geological cracks and one of the most iconic dive sites in all of Iceland.

At Silfra, divers descend a set of stairs installed for safety and access, and then enter a labyrinth of rock walls, boulder piles, cavities and crevices all filled with some of the world’s purest water. In fact, divers are encouraged to taste the water along the way!

Unique to Silfra, divers can actually reach out and simultaneously touch both the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. Diving here is akin to being transported to another world—with visibility exceeding 300ft (91m), temperatures hovering around 34°F (°1C) and a gentle flowing current, the dives are magical and transformative.

Topside wonders

Topside, Iceland is an amazing contrast between civilization, history and wilderness. With only 320,000 people residing in the entire country, many of them in the main city of Reykjavik, much of the country’s landscape is natural and undisturbed. Visitors can experience black, barren fields of pumice and lava stone, breathtaking waterfalls, lovely seaside communities and dramatic mountains.

Home to more than 30,000 live volcanoes, the land is relatively young and is still being formed. It is also a country steeped in history, including strong cultural ties to the Vikings, and is home to the site of the very first Parliament meeting in the year 930 AD.

In fact, visitors can experience the most exciting natural attractions Iceland has to offer in one afternoon by taking the Golden Circle tour. The Golden Circle is a very popular tourist route covering about 186.4 miles (300km). The tour loops from Reykjavík into central Iceland and back again.

There are a number of tour companies that offer this tour, most of which offer the following highlights: National Park Þingvellir, Gullfoss Waterfall, Strokkur Geysir and Kerið Volcanic Crater Lake. Some tours may also include trips to The Blue Lagoon, Skálholt church, and the Nesjavellir geothermal power plant.

Afterthoughts

If you are an experienced cold-water diver in search of underwater geological adventures, put northern Iceland high on your list. Where else can you take a thermos on your dive, fill it with hot, geothermal water, and make some hot chocolate with 1,100 year old water with it before returning to the dock? ■

The authors wish to thank Dive.IS (dive.is) and Strytan Dive Center (strytan.is). Michael Salvarezza and Christopher P. Weaver are underwater photographers based in New York. For more information about this and other expeditions, visit: ecophotoexplorers.com/iceland.asp