Seen from space, Isabela Island—the largest island of the Galápagos archipelago— reminds me of a giant seahorse facing the great blue yonder of the Pacific Ocean. As one approaches land, the cap of thin white clouds dissipates. Isabela’s majestic landscape is a perfect alignment of shield volcanoes, rising above 1,000 metres, which stretches from the southeast to the northwest. Among them, Wolf Volcano reaches 1,700 metres.

Contributed by

Straddling the Equator, it is the highest summit of the Galápagos group. Over the last 700,000 years, the six volcanoes of Isabela Island—Cerro Azul, Sierra Negra, Alcedo, Darwin, Wolf and Ecuador—have evolved into gigantic calderas. Following successive rises and falls of magma, the rim of a volcano collapses into the crater. With a diameter exceeding 10km, Sierra Negra is by far the largest of the island’s calderas.

The Galapágos are a renown hotspot of the east Pacific, and Isabela is the most active volcanic island. The last eruption dates back to 2005. An incandescent lava flow filled the crater and turned into a fascinating experience for the locals, who witnessed the show at sundown.

Daily flights on EMETEBE’s Twin Otters from Baltra to Puerto Villamil take only 30 minutes. Upon final descent, the small propeller airplane flies over Los Islotes Cuatro Hermanos—aka The Four Brothers. These tuff cones of pale brick red color have been eroded by wave action of both the South Equatorial Current and the Cromwell Current. Two of the islets have been chiseled into moon crescents gaping towards the south. Easily accessible by boat from Puerto Villamil, the ‘4 Hermanos’ islands—as they are called locally—offer a number of good dive sites.

On the port side, one marvels at another huge crescent fringed by a ring of white surf. Tortuga Island, also known as ‘Brattle’, is a refuge for seabirds. Nazca boobies, tropicbirds [ed.— family of tropical pelagic seabirds of the Phaethon genus] and large frigate birds nest on the outer slopes of the crater.

A stone’s throw away to the north, La Viuda (The Widow) juts out of the ocean like a grim stoney finger pointing to the sky. That is all that is left of a tuff cone totally destroyed by the elements. In its formidable solitude, it doesn’t look like much, but somehow, it is one of the best dive sites—only 20 minutes away from port. A resting place for blue-footed boobies, it also attracts a few sea lions basking lazily in the golden light of the afternoon sun.

As the avioneta, or light aircraft, does its final loop above the bay of Puerto Villamil, one is thrilled by the pastel green and emerald colors of the waters, fringed by the black lava.

Successive trains of waves come towards the shore only to fall apart into snow white foam upon this tormented coastline. A long sandy beach stretches west towards the dark hills, once the site of an infamous penal colony (1946-59). This is an arid, hostile landscape where the vegetation is composed of palo santos trees, opuntia and candelabra cacti, and spiny shrubs.

Everything here forecasts extreme conditions, a sharp contrast with the idyllic cliché found on Isabela Island. Welcome to the ‘Enchanted Islands’ where the hidden side of paradise reminds one of the ruthless reality a world apart and its fabled history.

History

In 1897, Don Antonio Gil Quezada built a hacienda in Santo Tomas in the highlands of Isabela Island. He had earlier made the unfruitful attempt to establish a colony on Floreana, an island further south, which had the advantage of a freshwater spring. In the old days, sulphur deposits of the Sierra Negra Volcano were exploited and brought to the coast on the back of donkeys.

After WWII, the Ecuadorians retrieved the installations of the U.S. Army, who had created a radar base behind Cerro Orchilla. One morning in 1946, the penal colony, Colonial Penal de Isabela, opened its gates to 300 convicts who disembarked from the BAE Abdon Calderon of the Ecuadorian Navy, escorted by 20 policemen and ten officers. These men were sentenced to hard labour under the hot sun in what would become known as the harshest prison of the Galapágos.

Criminals, political prisoners, petty thieves and other unwanted citizens assembled under the unforgiving whip of the guards. The convicts were forced to build a stone wall of volcanic dry blocks, which grew to 80 metres long, 8m wide and 8m high. It would eventually close the perimeter of their confinement. Many were said to have died in the building of this wall. Later, two camps were established in the highlands.

One morning on 9 February 1958, 22 convicts, who were bringing supplies to Camp Alemania on the slopes of the Sierra Negra Volcano, fooled the guards, getting them intoxicated with sugar cane alcohol. They took their guns and then attacked Camp Alemania and Camp Santo Tomas. They did the same at Camp de la Playa.

The mutineers were under the command of Pate Cucu who had declared: “I want an escape with no death.” Nevertheless, they did commit a number of rapes on their way to Puerto Villamil. “All that we want is to be free and leave these infamous islands and this dreadful prison,” the convicts said.

Finally, they seized two fishing boats and went on to James Bay on Santiago Island where they hijacked the American sailing vessel, Valinda. From there, they sailed to Esmeraldas on the Ecuadorian mainland. The penal colony was closed in 1959 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s publication, Origin of Species.

Diving

Diving Isabela is a different experience from diving Santa Cruz or San Cristobal islands. Isabela is the ‘far west’ of the archipelago in every sense of the word. The islets south of Puerto Villamil are at the crossroads of two major currents, meeting each other head on. The South Equatorial Current (also known as the Humboldt Current) moves from east to west during the dry season, with the help of the southeast trade winds, which blow from May to December. These cool waters have mean temperatures ranging from 18°C to 22°C.

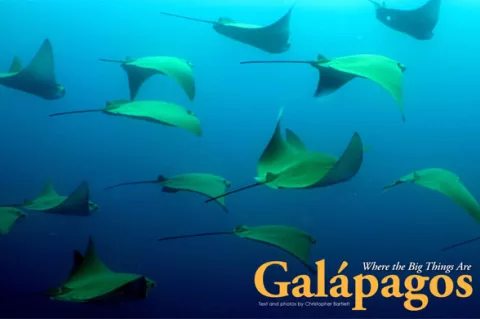

Originating from the Central Pacific, the Cromwell Current flows along the Equator, from west to east, at a depth of 300 metres. With a core temperature of 13°C, it creates an upwelling on the west and south coasts of Isabela and Fernandina islands. Nutrient-rich waters come up from the deep to the surface attracting a profusion of fish and gorgonians, 66 percent of which are endemic species. Consequently, the area is a playground for whales, mantas and orcas.

The Cromwell Current comes around the northern and southern tips of Isabela and meets the South Equatorial Current in the centre of the archipelago, triggering another upwelling. This current is responsible for the introduction of the giant freshwater eel (Anguila marmorata), which has established itself in the lagoons of Puerto Villamil.

A notable amount of endemic marine fauna is found west of the archipelago, with unique species such as the small Galapagos hornshark, which is cream-coloured with black blotches, and the harlequin wrasse (Bodianus eclancheri), which displays a chromatic variation from orange to white and black. Discovered by Darwin in 1835, the Galápagos sheephead wrasse (Semi-cossyphus darwinii) is recognized by a brown to purple color with a yellow blotch on the sides.

Deep and compressed, the white-spotted black tigris (Oplegnathus insigne) belongs to a unique family. Marlins, spadefish and sawfish are common pelagics in the area. In addition, the south of Isabela Island is an important nesting ground for the Pacific green sea turtle, which frequents a number of lagoons and beaches.

Los Islotes Cuatro Hermanos, or The Four Brothers, are tuff cones vigorously weathered by wave action. Three of them have been carved into moon crescents. It takes 45 minutes by fibra (short for Fishermen’s Fibrafort boat) to get there from Puerto Villamil.

Pyramid Island has a conical shape, with two rocks emerging southwards, left over from the original crater rim. A wall drops vertically on the outer slope, which is covered with brown gorgonians, yellow bushes of black coral and soft corals. At times, manta rays come to feed in the current. Hornsharks rest on ridges or hide under overhangs.

On the west side, the outline of the crater rim heads north at a depth of 28m, with a white sandy bottom on the right hand side and a drop off on the left side. Marble rays are often at play. Here, an old stem of black coral is covered with leopard anemones. Mixed schools of metallic grey Peruvian grunts and Galapagos grunts (silvery with a yellow eye) roam the area. Sea turtles and sea lions are rather active, and the Galápagos blue porcupinefish is common.

A school of steel pompanos (diamond-shaped fish with a swallow tail) often engulfs divers during decompression stops.

The two horns of Moon Island define a little bay, washed by surf. Underwater, the site evolves around a pinnacle, with a whirlpool of life—harlequin wrasse, spotted eagle rays, blue and gold snappers. I was thrilled to spot an orange Pacific seahorse here—just 25cm tall—which swam near the bottom. In the shallows, hidden under an overhang bedecked with light brown and purple gorgonians, 15 spiny lobsters were on patrol with antennae fully deployed. A mouth-watering dish for sure, however, fishing with a scuba tank is strictly prohibited in the Galápagos!

In July 2001, I attempted a dive at Moon Island’s east point. The ocean was rather choppy, and the cape was wrapped in a cloud of bubbles. The current did not look too ominous, so I jumped into the water at a respectful distance.

The vertical wall was carved by a number of holes, which served as homes for sea urchins. The colorful site was dotted with blue and red sponges, black coral, soft corals, gorgonians and orange cup coral—the ideal biota for the blue-eyed damselfish, Cortez rainbow wrasse, large-banded blenny and a few species of gobies and octopus.

I was busy taking a photo of a long-nose hawkfish on a black coral when I suddenly sensed a presence behind me. Turning around, I got a real shock—a two-metre-wide sunfish, wide-eyed and bewildered, was staring at me as if I were from another planet. Stunned, I acted likewise!

This unusual fish looks like a giant triggerfish with dorsal and anal fins in the vertical axis moving sideways like a pendulum. It has a big head without a tail. The leather-like, silver skin has numerous dark blotches. Also known as the mola mola, the creature fixed a big, round, black eye on me. The mouth drew a perfect circle, mimicking pure astonishment.

This deepwater species belongs to the continental shelf, in the 200m depth zone. It feeds on benthic organisms, jellyfish, salp and drifting ctenarians. The mola mola comes up to the shallows (20m), when it needs to be cleaned by wrasses. It is even seen at the surface where seabirds also do the job. It prefers areas of upwellings and converging currents, as is also the case in Bali.

Two species of sunfish are found in the Galápagos, the other one being Ranzania levis. A new Masturus species was discovered in April 2008. [See www.expeditions.com/theater17.asp?media=561]

Three weeks later, I did a dive at Crescent Island—the third of the 4 Hermanos group. Once again, I encountered a sunfish at a depth of two metres. The biggest island has on its northern shore a long tunnel that runs into the volcanic tuff. The entrance to the cave is 13m deep, and the tube finishes in a dead-end after 70 or 80 metres. This is a refuge for lobsters, stingrays, whitetip sharks and sea lions at play. A gentle slope is found outside the cave, with scattered boulders. Mexican hogfish, grey grunts, harlequin wrasse, king angelfish and seahorses are found there. Even mantas pass by occasionally.

La Viuda

Seen from the sky, Tortuga Island is a visual enchantment. The flooded crater is broken for most of its southern part, with two small islets pounded by the surf. I flew over the island one clear morning in February 2006 and allowed the pilot to take me into a rising spiral to give me “a better view”, as he put it. Tied by a rope around my waist, I was in the luggage hold taking pictures through the open hatch—not the best moment for a drop!

Northeast of Tortuga, La Viuda is barely seen at water level. The inconspicuous, rocky finger mimics a black thumb covered in bird poop. My favorite dive site, it is a true aquarium bathed in the northeast current. It is definitely not a good choice for novices; the drop-off plummets down to 40 metres on the sandy floor of the crater.

A unique Galapagos species is found at depth—the blanquillo, or ocean whitefish (Caulolatilus princeps). Squads of golden rays skim the bottom.

Following the inner slope of the crater, one discovers a series of small pinnacles—remains of the rim—alternating with some passes where the current is felt. Clouds of fish materialize into the blue—a school of barracudas and spotted eagle rays in formation. Sometimes bat eagle rays join the ballet. They are olive green, dorsally, and white, ventrally, with a very long tail and a rounded head. On other days, schools of tuna, yellowtail scad and Spanish mackerel show up. Even Galápagos sharks and hammerheads can be seen. The dark shape of a black manta always comes as a surprise!

Closer to the rocks, yellowtail surgeonfish, king angelfish, barberfish, three-banded butterflyfish, humphead parrotfish, bacalao grouper and myriads of creolefish dot the scene. Various species of sea stars are found at La Viuda. Should you be lucky, the carnivorous nudibranch, Roboastra sp., will reveal itself with black, yellow and blue stripes. It is the predator of the smaller Tambja mullineri nudibranch, which is striated black and turquoise blue and is endemic to the Galápagos Islands.

Tortuga

For an easy shallow dive with no current, head for the north coast of Tortuga where one will find gentle slopes, volcanic sandy patches in between ridges of tuff (light, porous rock of consolidated volcanic ash), small drop-offs and overhangs. The site is appropriate for dive courses. Species there include the Galápagos porgy, soldierfish and squirrelfish, guineafowl puffer, soapfish, dusky chubs, scorpionfish and the charming Pacific snake eel, with its creamy color and rounded black spots, foraging among the rocks.

Stimulated by the steady current flowing south, the east coast of Tortuga towards the point is more animated. The underwater scene is rugged with canyons, pinnacles, small drop-offs and boulders. Sea turtles, sea lions and stingrays are the norm here.

The particularity of the site is the presence of a great number of flat, oval-shaped nudibranch, which are whitish with orange spots and gills. This species of Galápagos doris is probably endemic and is yet unidentified. It prefers cool waters, under the thermocline with temperatures of 12°C to 19°C at an optimal depth of 25m. The Galápagos doris nudibranch nests itself in cavities carved by sea urchins, on big boulders exposed to the current.

Another species of nudibranch divers encounter is Glossodoros dalli. A large triton—the Panamic horse conch—is also found on rocky substrates. It has red flesh dotted with blue. Some nice specimens of scallops hide under overhangs.

The southeast point ends abruptly with a sheer wall, plunging vertically to 50m. This is a wild spot where anything can turn up—Galápagos sharks, manta rays, eagle rays and cownose rays, sunfish, dolphins and schooling hammerheads hunting prey.

Back in March 2005, at the heart of the ‘Galápagenian’ summer, I did a dive at the tip of El Triangulo, the islet south of Tortuga, which is exposed to the swell of the open ocean. On this occasion, I came upon an unusual endemic species of nudibranch—the flat, oval Carolyn doris, which is brown with white blotches.

As we came out of the water, my companion pointed her finger towards the bay of the crater. “Over there! Dolphins!” she shouted. Somehow, neither the back nor the dorsal fin (which was very tall) coincided with the norm. “Holy (bleep)! These are orcas!” I was stupefied. I couldn’t believe my eyes. Luck was smiling upon us. This rare sight put me in a trance at once. Five killer whales frolicking in the bay is an opportunity not to be missed. “Wait for me!” I yelled. I signaled the boatman to stop the outboard motors and changed the macro lens on my camera for the wide angle lens.

Godfrey Merlen, a specialist on cetaceans and longtime resident in Galápagos, did some research on these fascinating dolphins between 1992 and 1999. Statistics showed that at least 135 sightings had been made; most of these were made while the orcas were hunting at the surface. Common prey of the orca include sea lions, sharks, hammerheads, stingrays, mantas, sunfish, turtles, dolphins, whales and sperm whales—you name it. A top predator, it is known as the hyena of the seas. Man is not on the menu though, but then again, it’s yet to be seen.

Ready for the big jump, I gestured to the pangero (fisherman) to move on slowly towards the pod. One killer whale broke away from the group and came straight at the fibra. I swiftly slid into the water, holding my breath, and immersed myself right on the spot.

The formidable creature zoomed in on me like a torpedo. I framed it in the viewfinder of my Nikonos and fired the strobe at a distance of less than 3m. The beast avoided me slightly, overtook me and turned around immediately to have a better look. Exhilarating! This was pure adrenaline!

The orca swung around again, this time displaying a flashy, white abdomen and eyeing me in a comical way. The fur of the orca is so silky that it reflects the sunlight, creating an eerie blue aura around the animal. I shot various pictures in natural light, then broke the surface, exulting with total joy. Reassured, my friend joined me in the water, and we skin-dived with the orcas.

The dominant female passed underneath again, with a companion and a young calf, cruising just in front of us—an awesome, unforgettable moment! Life was simply here and now.

The Marine Reserve

Second in the world only to the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, the Galápagos Marine Reserve has a surface of 140,000squ km. First created in May 1986 following a presidential decree by Leon Febres Cordero, it was then labeled the Reserve of Marine Resources of the Galápagos and was half the size it is today.

The Master Plan of 1992 highlighted a number of conflicts of interest. As the years went by, repetitive abuses brought to light the illegal fishing of shark fins. Pirate camps of fishermen were discovered around Isabela and Fernandina islands.

The Galápagos were declared a Biological Reserve in 1996, but this did not solve the problem. Instead, it just added more fuel to the fire. Seminars organized by the Galápagos National Park, or Parque Nacional Galápagos (PNG), together with the Charles Darwin Research Station (CDRS) and Grupo Nucleo in 1997 brought the protagonists to the round table—the fishing sector, tourism, PNG, CDRS and the Ecuadorian Navy. As a result, a new master plan and a Special Law for Galápagos saw the light of day in 1998.

But UNESCO threatened to call the Galápagos a World Heritage Site in Danger (and now it is). Hence, came an update of the new marine reserve, which was an extension of 40 nautical miles beyond the extreme points of the archipelago. This was an increase of 70,000squ km to what it was earlier.

Blame evil forces, but the rampant corruption and abuses kept going on. Fishermen went on strike, taking over the installations of the Galápagos National Park Service—or Servicio Parque Nacional Galápagos (SPNG)—in 2004 by sacking the park offices in Isabela Island and continued to demand that recreational diving activities should be handed over to them.

Involved with politics of the Lista 5 (Demo-cracia Popular), they exerted pressure on the park to have new rights and work alternatives to compensate for the collapse of the pepino (sea cucumber) and shark finning industries. Eventually, dive cruises were paralyzed in 2007 (except for a few boats), and the diving activity reverted in part to the fishermen with their fibras. A new system of patentes, or licenses, for dive boats was created in June 2009. All together, 16 licenses were conceded by the Instituto Nacional Galápagos (INGALA). Meanwhile, the number of visitors to the Galápagos National Park approached the 200,000 benchmark.

Other attractions

Go on an excursion to Sierra Negra Volcano and take a horseback ride to Volcan Chico for panoramic views of Isabela Island. The last eruption dates back to October 2005. Or trek to the Muro de la lagrimas—the Wall of Tears—made of basaltic lava rocks, which is all that is left of the old penal colony. On the way, there are a number of places of interest including the lagoons of Puerto Villamil, Cerro Orchilla hill, the freshwater spring of El Estero, the lava tube and the enchanting beach of Tortuga Bay.

Visitors can also check out the Breeding Centre of Giant Tortoises of the Galápagos National Park or visit the islet of Tintoreras where one can see small whitetip sharks at rest. For snorkelers, there’s the marine site of Los Tunneles and the lagoon of Concha y Perla not far from Embarcadero, at the end of a boardwalk in the mangrove.

French born Pierre Constant’s intimate connection with the Galápagos Islands has thrived over 30 years. With a university background in biology and geology, Constant is a naturalist guide, underwater photographer, lecturer, expedition leader and author of three books on the Galápagos. Having built a lodge on Isabela Island, he’s now been a permanent resident of the Galápagos since 2002. For more information, visit: Scubadragongalapagos.com