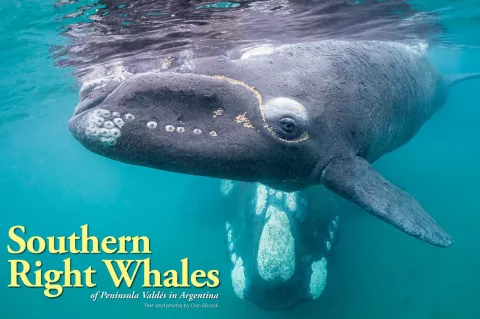

To be in the water with a southern right whale is a life-changing experience. Don Silcock shares his adventure in Argentina to photograph these majestic marine mammals, where he was lucky enough to see a rare white calf.

Contributed by

The key lies in how you enter the water… Slip over the side ever so gently and swim quietly toward them—always approach from the front, so that the mother can see you coming and assess the level of threat.

Ever vigilant of potential orca attacks and protective of her young calf, she will prioritise caution and cut short the encounter if she senses danger. However, she is weary from the constant stress of shielding and nourishing her hungry calf and yearns for a moment of rest. Get it right, and there is a good chance she will remain stationary, permitting you to draw closer.

If you are fortunate, she might even allow her curious calf to investigate you, the unfamiliar visitor, granting you the delightful experience of playful interaction with a boisterous calf measuring about five metres in length and weighing nearly eight tons!

And if luck truly smiles upon you, that calf might just be “El Blanco”—an exceptionally rare white calf, among the marvels of Argentina’s Peninsula Valdés, which serves as the winter sanctuary for the southern right whales of the South Atlantic Ocean.

To truly appreciate the significance of such a moment, a glimpse into the history of the whaling industry and its impact on these magnificent creatures is necessary.

The right whale to kill

It is said that in the early 1700s, the hardy men of that era gave these majestic creatures their common name for a rather straightforward reason—they were simply the “right” whales to kill!

Distinguished by their considerable size, relatively leisurely pace, and the rich source of whale oil they offered, these whales often swam close to shore to protect their vulnerable calves, making them easy to spot. Their generally placid temperament, and the unwavering commitment of mothers to their slower-moving offspring, made them prime targets for whale boats hastily launched from the shore.

Even after being hunted and brought down, the density of their blubber ensured that the carcass remained buoyant, making it easy towing to shore for the horrendous process of flensing and extraction of highly sought-after whale oil.

However, as the demand for this oil surged, so did the number of whalers. By the mid-1700s, the once-plentiful North Atlantic right whale population was in sharp decline, and shore-based whaling was inadequate to meet the escalating demand.

Much like recent years, the need for whale oil drove some major technological advancements and “Yankee” whaling ships emerged that could pursue whales far out to sea and process them on board—basically, the self-contained factory vessels of their time.

While the new whaling methods proved immensely profitable for their owners and investors in places like Nantucket and Long Island, the impact on the whale population was catastrophic. So severe was the decline that Yankee whalers were compelled to venture into the waters of South America, Indian Ocean, and as far as Australia and New Zealand, in their relentless quest for new whaling grounds!

Southern right whales

Much like their northern counterparts, southern right whales were prime targets for the voracious whaling fleets. By the mid-1800s, this industry had burgeoned into a multimillion-dollar behemoth, featuring hundreds of ships, many of them powered by steam and armed with lethal gun-loaded harpoons.

Just as the northern whale populations had plummeted under this initial onslaught, so too did the southern whales’ numbers dwindle to the brink of extinction by the mid-1800s, rendering them no longer commercially viable targets.

It was not until 1936 that protective measures were finally enacted, but by then, the global population of southern right whales had dwindled to an estimated 1,000 individuals. Ironically, it was the post-World War II surge in the oil and fossil fuel industries that played a significant role in curbing the massacre of these majestic creatures, with those new industries able to meet the escalating demand for lighting, as well as petroleum-based fuels and lubricants.

Recovery

Nature possesses a remarkable capacity for self-restoration when we humans step aside, as evidenced by the gradual yet steady recovery of the southern right whale. This resurgence has been so significant that they are now classified as “Least Concern” (LC) on the IUCN Red List.

However, the northern right whales have faced a far grimmer fate. The North Pacific right whale, with an estimated population of just 500 individuals, is currently classified as “Endangered.” In the case of the North Atlantic right whale, the situation is even more dire, with a “Critically Endangered” status and a population of around 350, including fewer than 100 breeding females.

The key distinction lies in our actions in the northern hemisphere, where we have failed to step aside. Collisions with vessels in bustling shipping lanes and entanglement in commercial fishing gear have been the leading causes of fatalities.

Safe havens

The age of a deceased right whale is often determined by analysing its ear wax, revealing an average lifespan of approximately 70 years. As a species, they are known for their slow reproductive rates, with females reaching sexual maturity between eight to ten years of age and giving birth to a single calf after a year-long gestation period.

In the past, intervals between pregnancies were typically three to five years. However, recent research on northern right whales has unveiled a concerning trend. Females are now calving every six to ten years, and there are clear indications that their lifespans have been reduced to around 45 years. This decline can be attributed to the stress induced by vessel strikes and entanglement, further exacerbating their already precarious “Endangered” status.

Safe havens have played a pivotal role in the remarkable recovery of the southern right whale. Among these sanctuaries, none have been more vital than the sheltered gulfs of Peninsula Valdés in the southern Atlantic Ocean.

Peninsula Valdés

Situated in the northern region of Patagonia, Peninsula Valdés stands as one of Argentina’s most significant protected areas, encompassing a vast expanse of approximately 360,000 hectares. The peninsula is characterised by two expansive gulfs: the San José Gulf to the north and the Gulf Nuevo to the south, with a narrow strip of land connecting Peninsula Valdés to the mainland. It is a sparsely populated region, with limited infrastructure, and virtually no industrial development.

Peninsula Valdés is a dynamic landscape with shifting coastal lagoons, extensive mudflats, sandy and pebble beaches, active sand dunes and small islands. The varied terrain offers critical nesting and resting sites for numerous migratory birds, besides hosting several endemic species of camelids and rodents.

Yet, what truly sets Peninsula Valdés apart is the presence of its large gulfs, which provide a sheltered haven from the wild waters of the South Atlantic. And the unique environment serves as an almost perfect setting for the mating, birthing and nurturing of the next generation of whales, effectively contributing to the preservation of the species. With an annual visitation of more than 1,500 whales, Peninsula Valdés holds immense significance as a vital breeding ground for the southern right whale.

Enlightened conservation

There is much to appreciate about Peninsula Valdés, particularly in the way it is thoughtfully managed. While a single week in the area may not suffice to form a definitive opinion, it offers ample time to grasp the dynamics and determine if you are drawn to return for more—a true litmus test for being in the right place.

The journey toward recognising its unique status and how best to manage it commenced in the 1960s with the establishment of the first nature reserves. In 1974, San José Gulf was designated as a marine park, and this commitment deepened in 1983 with the creation of a comprehensive nature reserve covering the entire peninsula. Central to the overall endeavour was a special emphasis on fortifying the protection of the southern right whale, and in 1995, these marine reserves were extended five nautical miles out to sea, creating a genuine safe haven.

Implementing enlightened conservation practices is often easier said than done, but the practical execution at Peninsula Valdés is truly commendable, with the large numbers of southern right whales serving as its primary allure. Whale watching forms the linchpin of the economy in Puerto Pirámides, the quaint town serving as the peninsula’s ecotourism hub. During the season, hundreds of tourists embark daily at Gulf Nuevo to witness the mothers and their calves.

For those seeking an even more immersive experience, it is possible to enter the waters with the whales through a special permit granted by the Argentine Ministry of Tourism and Protected Areas, while under the vigilant supervision of designated wildlife rangers. The emphasis remains on maintaining a respectful distance from the whales, ensuring minimal disruption to their natural behaviour, and safeguarding the well-being of individuals sharing the waters with these magnificent but massive creatures.

El Blanco—the White One

Sharing the water with large creatures is an inherently special experience, and the degree of specialness usually depends on the animal’s disposition towards your presence. Some creatures may want nothing to do with you, while others seem to relish the company.

In my experience, whales tend to be quite accommodating and spatially aware. They possess an uncanny sense of your location and adjust their movements accordingly—a reassuring trait considering the potential damage their massive flukes and tails could inflict!

The southern right whales of Peninsula Valdés exhibited a similar demeanour, provided one approached them with care. Being in such close proximity to these unusually shaped giants had the potential to be life changing.

Over the course of five days spent in the water with them, encounters steadily improved as fellow divers and I gained confidence. However, it was on the final day that everything truly fell into place.

We had a premonition that something extraordinary was on the horizon when our boat crew collectively whispered, “El Blanco.” This meant that the rare white calf we had briefly glimpsed earlier in the trip had returned. White calves are exceptionally rare, accounting for just one percent of each year’s newborn whales in the area.

What made this encounter even more exceptional was that “El Blanco” was in a curious and playful mood, evidently taking cues from its mother that it was safe to investigate us. For stretches of up to 15 minutes, the calf engaged with us by approaching closely and then playfully veering away, akin to the spirited antics of a puppy.

We took every possible precaution to avoid physical contact, but even when the calf came so close that we could practically reach out and touch it, it seemed to possess an innate awareness of our presence, turning away at the last moment.

Throughout this incredible interaction, “El Blanco” kept its tail passive, ensuring our safety. For our part, we were utterly in awe and profoundly inspired by the spectacle before us, and fear was conspicuously absent from the equation.

In summary

In the past, both the northern and southern right whales teetered on the precipice of extinction, with their populations decimated by the relentless, industrial-scale pursuit of commercial whaling. Today, the northern variants still teeter on that precipice, their long-term prospects appearing bleak unless significant changes occur. However, the southern whales tell a different story—a tale of resilience and remarkable recovery. While there is still work to be done, the signs are undeniably positive.

The safe havens of Peninsula Valdés have played an instrumental role in bolstering the southern Atlantic Ocean population. Witnessing first-hand how these whales utilise these havens was a profound privilege. ■

SOURCES:

SMITH TD, REEVES RR, JOSEPHSON EA, LUND JN. (2012). SPATIAL AND SEASONAL DISTRIBUTION OF AMERICAN WHALING AND WHALES IN THE AGE OF SAIL. PLOS ONE 7(4): E34905.

RICHARDS R. (2009). PAST AND PRESENT DISTRIBUTIONS OF SOUTHERN RIGHT WHALES (EUBALAENA AUSTRALIS). NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY, 36:4, 447-459.

NOAA. (2017). NORTH PACIFIC RIGHT WHALE (EUBALAENA JAPONICA) FIVE-YEAR REVIEW: SUMMARY AND EVALUATION. NOAA FISHERIES.

REEVES RR, MITCHELL ED. SHORE WHALING FOR RIGHT WHALES IN THE NORTHEASTERN USA.

SUEYRO N, CRESPO EA, ARIAS M, COSCARELLA MA. 2018. DENSITY-DEPENDENT CHANGES IN THE DISTRIBUTION OF SOUTHERN RIGHT WHALES (EUBALAENA AUSTRALIS) IN THE BREEDING GROUND PENINSULA VALDÉS. PEERJ 6:E5957

WIKIPEDIA