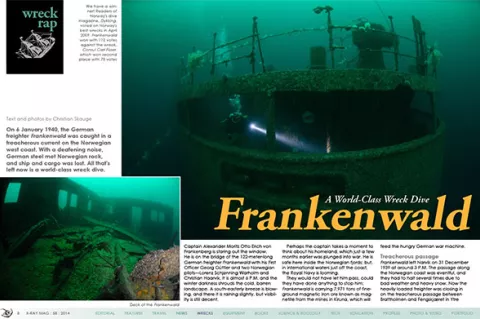

On 6 January 1940, the German freighter Frankenwald was caught in a treacherous current on the Norwegian west coast. With a deafening noise, German steel met Norwegian rock, and ship and cargo was lost. All that's left now is a world-class wreck dive.

Captain Alexander Moritz Otto Erich von Frankenberg is staring out the window. He is on the bridge of the 122-meter-long German freighter Frankenwald with his First Officer Georg Güttler and two Norwegian pilots—Lorenz Schjønning Warholm and Christian Haarvik. It is almost 6 P.M. and the winter darkness shrouds the cold, barren landscape. A south-easterly breeze is blowing, and there it is raining slightly, but visibility is still decent.

Contributed by

Perhaps the captain takes a moment to think about his homeland, which just a few months earlier was plunged into war. He is safe here inside the Norwegian fjords; but, in international waters just off the coast, the Royal Navy is looming.

They would not have let him pass, could they have done anything to stop him; Frankenwald is carrying 7,971 tons of fine-ground magnetic iron ore known as magnetite from the mines in Kiruna, which will feed the hungry German war machine.

Treacherous passage

Frankenwald left Narvik on 31 December 1939 at around 3 P.M. The passage along the Norwegian coast was eventful, and they had to halt several times due to bad weather and heavy snow. Now the heavily loaded freighter was closing in on the treacherous passage between Brattholmen and Fengskjæret in Ytre Steinsund, just north of the mighty Sognefjord.

The captain orders slow speed on the engine room telegraph as they draw closer. The atmosphere on the bridge is presumably tense, and von Frankenberg later stated that he was having doubts about the pilots after taking them on. Before making his way to the chart room to check their position one extra time, he notes that they are in the correct sector of the lighthouse ahead.

Von Frankenberg had not wanted to pass through the narrow strait at this hour, but their intended anchorage at Larsråholmene further north was filled up with about a hundred or so fishing vessels because of bad weather during the last few days. He had no choice but to continue south and head for Bergen, running through the night.

When von Frankenberg returns to the bridge, he discovers that the light from the lighthouse has changed. The current must have pushed the freighter slightly off course to starboard, and now they are in the wrong sector. Suddenly, lights from a small vessel travelling in the same direction appear in the darkness ahead.

The Wald class

Measuring almost 400 feet, Frankenwald was a big ship for her day and age. The total capacity of 5062 GRT meant she could take a lot of cargo in her four main holds. She even had a number of passenger cabins in the superstructure amidships. She was built in steel and equipped with a triple-expansion steam engine giving her a speed of 11 knots.

The freighter was launched in 1921 as build number 36 from Deutsche Werft in Hamburg and went into service the following year. She had been commissioned by the German shipping company HAPAG (Hamburg Amerikanische Paketfahrt Aktiengesellschaft, or Hamburg-America-Linie) in 1918. They had a very close relationship with the shipyard, being one of the investors along with the engine manufacturers Gutehoffnungshütte and AEG.

From 1921 to 1923, Deutsche Werft built no less than ten freighters in what was to become known within HAPAG as the Wald class. The shipyard was remarkably efficient, and during WWII, they turned out a total of 113 Type IX and XXIII U-boats for the German Kriegsmarine.

Apart from Frankenwald, the Wald class consisted of the ships Niederwald, Steigerwald, Westerwald, Wasgenwald, Idarwald, Kellerwald, Schwarzwald, Spreewald and Odenwald. They were all similar in construction and tonnage, even though only two of them were actual sister ships. HAPAG also incorporated two ships they had bought abroad in the Wald class—Sachsenwald and Grünewald.

Only two of the Wald class ships were to survive WWII. Odenwald and Schwarzwald were scrapped in 1949 and 1963. The others fell victim to submarine attacks or mines.

Seconds from disaster

Back in Steinsundet, Captain von Frankenberg, the First Officer and the two pilots are intensely focused. On a northern approach, the narrow strait makes a sharp turn to port, and Frankenwald needs the entire shipping lane to make it safely through. Not wanting to overtake the smaller vessel in front of them—a fishing boat—at the narrowest point, half-speed is ordered. Not only does the presence of another vessel limit Frankenwald's room to manoeuvre, but the heavily loaded freighter is also more exposed to wind and current at low speed.

The pilots and officers had anticipated a northerly current through the strait, but instead, it was pushing hard to the west. Captain von Frankenberg suggests to the pilot that they should turn ten degrees port, surprised they have not already done so. He is worried about the turning radius and the heavy cargo, which gives Frankenwald an average draft of eight meters. Only then does the pilot react and calls out the order—port rudder.

For a few seconds, nothing happens. The ship does not come around! Von Frankenberg assumes command, and ignoring the pilots, he orders full port rudder. The command is repeated correctly by the 53-year-old helmsman, Emil Förster, but again nothing happens. Pushed further by the current, they are getting dangerously close to Brattholmen on the starboard side. Von Frankenberg realizes what is about to happen and orders full speed ahead in an attempt to regain control of the ship. It is too late.

German steel meets Norwegian rock

Frankenwald runs aground on Brattholmen, and her belly is torn up, not far behind the bridge. She is slowly starting to come around, but then she hits bedrock for a second time. It is severe, and the freighter is doomed. The sound of German steel crashing into Norwegian rock must have been deafening, and the entire ship shakes violently.

The engine room immediately reports that water is flooding in. A wireless SOS signal is transmitted and picked up by Bergen Radio about 50 miles (78 km) further south; the torpedo boat Brand is dispatched to the stricken freighter.

About ten minutes later, the lights go out. Fearing the boilers might explode, Captain von Frankenberg sounds the alarm—one long and three short bursts. Three of the four lifeboats are lowered (one has been damaged in a collision earlier), and the crew of 48 leaves Frankenwald. They are picked up by nearby fishing boats.

The first officer later reported that the ship was left in “good order”. A radio transmitter, a suitcase and a seaman’s bag were the only things salvaged, along with the ship's log, bridge log and engine manoeuvre log.

Frankenwald drifts into a calm bay and sinks in deep water (40+ meters) about one and a half hours later.

When the torpedo boat from Bergen arrived at the scene, it was all over. They returned with the Frankenwald crew, who shouted, “Long live the torpedo boat crew!" when they were safe at the dock and under the care of the German consul. Captain von Frankenberg later wrote that all Norwegians they were in touch with were extremely helpful and accommodating. The relationship between Norwegians and Germans probably was a lot better than three months later, after the German attack on Norway.

Local suspicion and rumours

A maritime inquiry was held in Hamburg on 16 January 1940, under the watchful eye of Oberlandesgerichtsrat Dr Reinbeck and no less than five captains and an administrative assistant. In short, the pilots were blamed for the ship running aground. In the eyes of the inquiry board, they should have anticipated that the ship might be pulled off course by the current.

The captain and officers of Frankenwald were acquitted, and the shame remained in Norway. There was no mention in the maritime report that any of the pilots were present at the proceedings, which seemed to have been an all-German affair.

The Norwegian newspaper

Bergens Tidende reported two days after the accident that Frankenwald also had rudder problems earlier on her journey, and icily stated that they understood it was the same helmsman responsible at the time Frankenwald ran aground.

After the accident, rumours soon started to circulate. It was speculated that Frankenwald was actually heading north and that the route, ship and cargo seemed mysterious. Locally, it was said that Frankenwald possibly had unloaded somewhere in the Sognefjord, but no evidence to support this was produced.

When looking at the position of the wreck, it is indeed very difficult to understand how Frankenwald could have ended up where she is. It seems much more likely that she was heading north, but the statements made in the maritime inquiry firmly contradict this. The data given on the direction of winds and currents support the location, and there seems to be no misunderstandings or discrepancies in the captain’s report.

Locally, questions were also raised regarding the cargo Frankenwald was carrying. Today, the holds seem mysteriously empty—in fact, divers who have been down there to investigate state that there is nothing to be found.

The salvaging company Brødrene Anda raised the steel propeller and the anchors in the 1950s, but there is no record of them salvaging any cargo. Still, this would have been entirely possible; the magnetic iron ore was fine-ground and could have been sucked up with pumps and hoses. This would not have been a high-paid job, but good enough during times of little work. It would also explain the total lack of damage on the wreck—the booms are still in place over the open cargo holds.

Voted “Norway’s Best Wreck”

Even if the story of Frankenwald may be somewhat mysterious, there is no doubt as to what happened three months later; war broke loose in Norway on 9 April 1940, and both Norwegians and Germans had other priorities. Frankenwald was left to her own devices in her wet grave, and with the exception of the salvage work, she was left alone until sport diving gained popularity a few decades later.

In the last 30 years or so, Frankenwald has been visited by thousands of divers. Some of them were souvenir hunters who unfortunately have helped themselves to some of the treasures—but there are still many interesting things to see.

The wreck is in remarkably good condition, even after 70 years on the bottom. Frankenwald actually looks largely intact, and even the masts are still standing. This is due to the wreck being in a very sheltered location, and the fact that she is upright on the bottom.

In 2009, Frankenwald was voted "Norway’s Best Wreck" by the readers of the Norwegian dive magazine, Dykking. Competing with wrecks all along the Norwegian coast, Frankenwald was well ahead in the vote, and many people were expressing the great experiences they had diving the wreck.

Frankenwald truly is a majestic shipwreck—some even say it is a world-class dive. Having visited her several times, it is hard not to agree.

To dive the Franken-wald, it is necessary to have a boat and surface support. There might sometimes be strong current at the surface, but usually, it's calm down on the wreck itself. The nearby Gulen Dive Resort, a PADI and BSAC centre, runs regular trips to Frankenwald.

A world-class wreck dive

The easiest access is to descend and ascend along the aft mast, which starts just seven meters below the surface. This provides an excellent starting point to dive both the stern and midship, and you might even reach the bow—but this might cause bottom time problems unless you dive on something other than air. Although a little more challenging, it is possible to start and end the dive on the foremast.

In any case, Frankenwald is so big that several dives are required to explore the entire wreck. The huge dimensions that come into view when you sink down along the mast are truly impressive—a giant shadow below you, big as a mountain.

The stern is at about 24 meters depth, and all the way aft, you will find the remains of the jury rudder. The railings are embellished with colourful dead men’s finger soft coral, and the stern is beautifully intact, apart from the wooden deck, which is all but consumed by shipworm. This is not a disadvantage—it provides an excellent view of Frankenwald's innards.

The enormous steering gear can be seen below the remains of the upper deck, and the different compartments and passageways almost form a labyrinth. Several gas tanks are leaning up against one of the walls, and it is easy to penetrate what is left of the superstructure without any great risk—there is no roof.

Swimming through the galleries on either side of the aft superstructure is a great experience. After you pass the huge bollards, you should swim through one of the openings aft and out into the water. When you turn around, you are met by what is perhaps the most stunning view of the whole wreck. The stern looks almost like the conning tower of a giant submarine, with two elongated openings at the top.

Another great way to get to this spectacular sight is to sink down along the side of the hull just in front of the aft superstructure and swim through the opening between the hull and the rudder where the propeller used to be—all that remains is the cut-off axle. It is deep, but when you are heading back up, you get to see the majestic stern in all its beauty.

Sometimes pollock are schooling above the stern and around the aft mast. The current can sometimes be quite strong, but normally it is just a slow drift. The mast that stretches towards the light on the surface creates a fairytale-like ambience, a taste of a lost world. It is not hard to understand why some divers come back again and again. Frankenwald is simply magical.

Huge holds, but no cargo

In front of the aft superstructure, ladders on either side of the ship lead down to the main deck where two of the four main holds are located. Huge winches are placed below the mast, which is fitted with six booms—three pointing forward and three towards the stern.

The loading booms are intact and lay over the ghostly, open holds. Looking down only reveals empty darkness, even when aided by a powerful torch. Where is the iron ore? If it was not salvaged, there could be some truth to the old rumours about the Frankenwald mystery.

It has to be said that iron ore is very heavy and does not fill much—and Frankenwald has huge holds. The 17m (54ft) width combined with an 8m (27ft) depth gives a total volume of 8,000+ cubic meters if you assume that the four holds make up about half the length of the ship.

Iron ore weighs about two tons per cubic meter (according to online sources) which means Frankenwald should have had about 4,000 cubic meters of cargo—almost half her volume capacity. This means there must have been a salvage operation at some point. If not, the rumours surrounding Frankenwald's cargo and direction of travel might have some truth to them.

Galleries and penetration

When swimming further forward on the wreck passing the second hold, the superstructure amidships soon comes into view. The ladders lead up to the second deck, and you can choose to swim above the superstructure or go through the gallery on either side along the main deck. On the second deck, the empty davits of the lifeboats are standing as silent witnesses to the drama that was played out here on a Saturday evening in 1940.

Most divers choose to do the deepest swim along the main deck first and then go shallower along the second deck when they return. The superstructure can easily be penetrated, and this is where access to the boilers and engine room is found. There is a lot of silt inside the wreck, so penetration must be done with extreme caution—and naturally, only by divers with proper equipment, experience and training.

Further forward is a third, smaller hold that was used for the coal needed to keep the ship running. In front of this is the main superstructure. The bridge and wheelhouse have collapsed, and only about half of the walls remain on the upper deck. The main deck is still in good shape as well as the cabins for the crew and captain. If you penetrate one of these cabins, there is an amazing sight waiting for you—a bathtub, a toilet and a mirror that is still hanging on the wall.

On the fo’c’sle

The forward part of Frankenwald is just as interesting and beautiful as the stern. In front of the wheelhouse, there are two more open holds, and the foremast is still standing. Even here the loading booms are intact, laying over the holds as if they are just waiting to be hoisted by the deck crew. There is no sign of any cargo or salvage work here either.

On the 40ft-long fo’c’sle (forecastle) everything is intact, and it is difficult to grasp that the ship ran aground and sank; from above, everything looks perfectly all right. The bollards are ready to accept mooring lines, the hatch to the chain locker upfront is open, and the windlass and powerful winches seem to be ready to spring into action.

If you have the time and opportunity, Frankenwald's bow is also a majestic sight. If you sink all the way to the bottom at 45+m, she towers over you just like on those old HAPAG posters. It is not hard at all to imagine the waves foaming at the straight bow while the crew is making ready on the deck. Frankenwald must have been a great sight in her heyday.

It is important to mind your time when exploring the bow section. The deck lies at 34m, and bottom time passes quickly. Before you know it, you may have serious decompression commitment, especially if you took your time getting here. It is wise not to try and explore all of Frankenwald on one dive. You will get a much better experience by splitting it up into several dives and concentrating on smaller parts of the wreck. You can easily do four to five completely different dives on Frankenwald—that is how big the old lady is.

An explosion of life and colour

The wreck lies just deep enough for it to have relatively little fouling. Apart from some huge, pink anemones, sea squirts and some dead men’s fingers, it is relatively untainted. Bright red starfish and sea urchins have made galleries, railings and other features their home, and the little white tubes of bristle worms are everywhere. I have even found scallops on the deck several times, and I still wonder how they get there.

When you are leaving the wreck along the aft mast, you only have to ascend a few meters before anemones are blooming, completely covering the huge pole. It is a beautiful sight in itself, and it also creates hiding places for a multitude of little fish and other animals.

Blennies, pipefish and decorator crabs are just a few of the species divers regularly encounter on the mast, and if you are lucky, you might even come across a bright red lumpfish steadfastly protecting its orange-yellow ball of eggs. Tiny ghost shrimp fence with their claws to catch food in the current, and incredibly colourful nudibranchs also find their way up here, far above the deck.

Many underwater photographers have been agonizing over that fact that it is impossible to change lenses underwater when they discover the teeming life on the mast. But let me leave you with no doubt—Frankenwald is most definitely a wide-angle dive! ■

Christian Skauge is an award-winning underwater photographer based in Oslo, Norway. For more information, visit: Scubapixel.com