The Florida sun was warm and high overhead as I donned my fins and slipped below the surface with camera in hand. A juvenile spotted eagle ray lazily glided away over the sand to avoid the impending intrusion of noisy bubbles and camera flashes. As I finned towards the shadows, I stopped to investigate a small male rosy razorfish in full breeding colors flitting about frantically, as I intruded on his territory. So consumed by the dance of the razorfish, I barely noticed the shifty dark mass in the distance making its way towards me.

Contributed by

Factfile

Adam St.Gelais holds a master’s degree in marine biology, and the research that comes with it has made possible his foray into underwater photography.

His current research focuses on the reproductive ecology of corals.

His studies have taken him from Alaska to Dominica with camera in tow.

You can see his photography and follow his travels at www.atsphotographic.com.

As I watched, the mass grew larger and more ominous as it drifted closer. I was still unable to discern what it was. Finally, the blob came into focus, and I was able to make out hundreds of wing tips and flashing white bellies writhing in the shallows.

A school of cownose rays, oblivious to my presence, swirled around me in a full feeding frenzy. As the massive aggregation of rays moved on, I turned my attention—and new-found exuberance—back to the shadows.

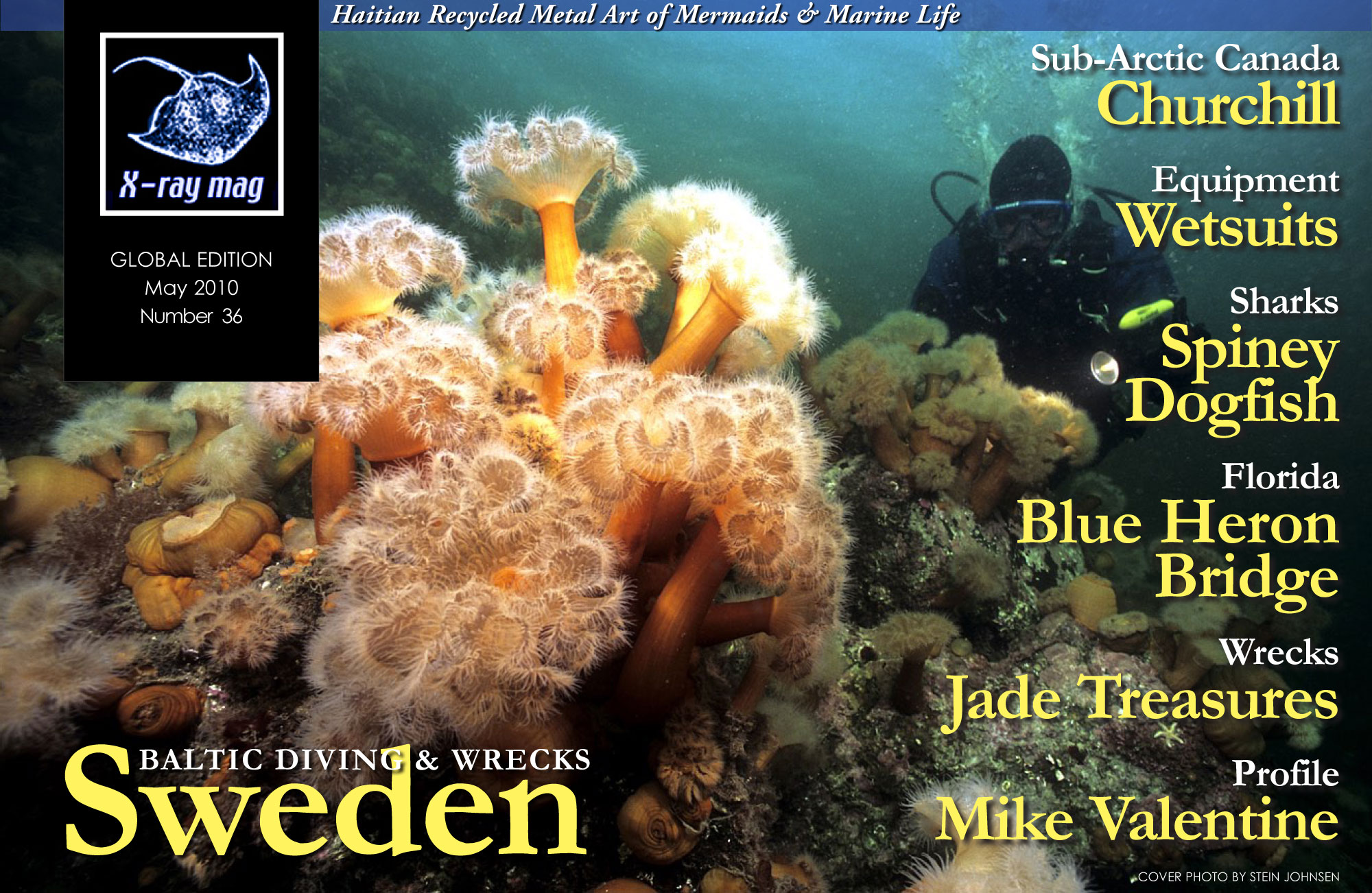

When you mention Florida to an underwater photographer, visions that spring to mind tend to be those of beautiful reefs and haunting wrecks from Key West to Key Biscayne. This is for good reason. The Florida Keys could be argued to be the birthplace of underwater photography, and the ecosystems there have fostered the careers of some of the world’s underwater image pioneers. But to those in the know, there are plenty of photographic opportunities for photographic adventures in Florida well beyond the Keys, which are easy to get to, easy on your wallet, and just as exotic.

Case in point, the Blue Heron Bridge in Riviera Beach, Florida. Whether you are taking a camera beneath the surface for the first time, or you take two full SLR set-ups with you—in case you want to shoot macro and wide angle in the same dive—this is a place you need to experience.

Unexpected diversity

The Blue Heron Bridge is by no means a secret. Spanning the intracoastal waterway, the bridge shades an ecosystem that is one-of-a-kind—blending the tropical and the subtropical. It has attracted divers for decades. The bridge is un-divable for most of the day. Tidal currents are amplified through the narrow bridge passageways, and the visibility is classified as “I can’t see my own hand in front of my face.” The narrow window for us to slip below and explore this unique site opens up just one hour before high tide, as clear blue ocean water is forced in through the Lake Worth inlet, which sits just south of the bridge and washes beneath. Depending on the tide, visibility can increase from tens of centimeters to tens of meters in a matter of minutes. The transformation is striking to say the least.

Not only does the bridge’s proximity to the Lake Worth inlet make diving here possible, the pulsing tidal fluctuations that periodically inundate the bridge with water from the Atlantic also makes possible the incredible and unexpected diversity. Converging currents push in the planktonic larvae of a mixture of animals normally found on coral reefs and those from subtropical environments. Here, under the shelter of the bridge, they mingle and settle, adding to the establishment of a rare ecological hodgepodge of organisms. Where else can you see arrow crabs and horseshoe crabs in the same dive? Or schools of cownose rays, followed by a manatee? Under the Blue Heron Bridge, you never quite know what you will see. Which is why I keep going back. I have yet to be disappointed, and have taken some of my favorite photographs there.

What you need to know

Don’t expect to just show up and dive at the Blue Heron Bridge. This dive requires a bit of research before hand. Make sure you check the tides ahead of time. Arrive 1.5 hours prior to high tide to allow time to assemble dive and camera gear, and then get wet a full hour before high tide. At an hour before high tide, visibility will be good, but there will still be some current. For this reason, many divers will wait until 30 minutes before high tide to get in. If you don’t mind a bit of current, getting in before everyone else is worth the extra fin kicks.

The deepest point is less than 7m, so it is more likely that your bottom time will be dictated by the tides and not your air. You will know it is time to get out when the visibility starts to decrease as the tide begins to go out. Generally, the visibility will drop before the current picks back up, so once you notice this, it is a good idea to head back to shore before the current picks up too much, which can make your egress difficult.

Bring a light. Even at high noon on a sunny day, the lighting directly under the bridge may as well be the dead of night.

Speaking of night, diving the bridge after the sun goes down brings out a whole different group of animals and is well worth the effort especially on a full moon, as the accompanying spring tides push the oceanic water further inshore. Parking is not allowed at night, however, and unidentified cars are ticketed. Luckily, this is easily remedied. Most local dive shops keep close tabs on the tides and often organize group night dives at the bridge that anyone is free to join. Just show up a the dive shop ahead of time, put your name and license plate on the list, and the dive shop will make sure you surface without a parking fine stuck to your windshield.

Getting the shot

From a photographer’s point of view, it is hard to decide what to be prepared to shoot here. Subjects range from infinitesimally small nudibranchs to the occasional blimp of a manatee cruising over head, but unless you’re looking for pier type wide-angle shots, a macro lens will be your best bet. Just don’t blame me when the manatee family shows up, and they won’t fit in the frame.

One benefit to shooting under the bridge is that, for better or worse, animals here have become completely habituated to the presence of divers. While we could argue about the ecological ramifications of this all day, it does make getting the shot easier, even for those new to underwater photography. Normally skittish angelfish and spadefish practically swim up to greet you.

Besides the obvious angelfish greetings, make sure to keep an eye trained on things you would not normally look at. Many of the rarest and most interesting inhabitants of the bridge like the lined seahorse—a rare sighting in Florida—are well camouflaged against the tangled mass of hydroids and algae. Further still, many photo-worthy and rare animals—like the Scotch bonnet snail, which spends the daylight hours buried deep in the sand—emerge only under cover of darkness.

So, the next time you’re vacationing in Florida, take a day away from the crowded, expensive charter boats and see what you can find in some places you would not expect to dive. I have seen some of the best reefs and wrecks that Florida has to offer, but if the tides are just right for a quick weekend dive with good promise for creating great images, you’ll know where to find me. ■