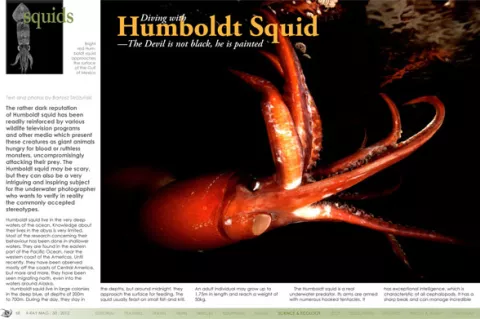

The rather dark reputation of Humboldt squid has been readily reinforced by various wildlife television programs and other media which present these creatures as giant animals hungry for blood or ruthless monsters, uncompromisingly attacking their prey.

Contributed by

Humboldt squid live in the very deep waters of the ocean. Knowledge about their lives in the abyss is very limited. Most of the research concerning their behaviour has been done in shallower waters. They are found in the eastern part of the Pacific Ocean, near the western coast of the Americas. Until recently, they have been observed mostly off the coasts of Central America, but more and more, they have been seen migrating north, even into the waters around Alaska.

Humboldt squid live in large colonies in the deep blue, at depths of 200m to 700m. During the day, they stay in the depths, but around midnight, they approach the surface for feeding. The squid usually feast on small fish and krill. An adult individual may grow up to 1.75m in length and reach a weight of 50kg.

The Humboldt squid is a real underwater predator. Its arms are armed with numerous hooked tentacles. It has exceptional intelligence, which is characteristic of all cephalopods. It has a sharp beak and can manage incredible swimming speeds (24km per hour) with amazing agility. These characteristics give the Humboldt squid a highly efficient arsenal. The creature’s voracity is unlimited. When hungry, it simply eats, even other squid—cannibalism is common behaviour among the Humboldt.

The Humboldt squid is considered an underwater chameleon. It can change its colour rapidly from pure white to bloody red, traipsing through all the colours of the rainbow, even fluorescent. It is thought that their changing of colours is a type of communication tool used by these animals.

Catching Humboldt squid has become a profitable alternative to fishing for local people. Their good taste and relatively high price make the squid good business.

The area where squids are commonly caught, as well as studied, is the Gulf of Mexico, particularly in the area of Santa Rosalia, but most recently, due to migration, also the Bay of Los Angeles.

To catch the squid, fishers use special cylindrical, fluorescent hooks. The hook looks like a rotated conifer twig with steal needles. The fishing technique appears quite simple. The hook is attached to a fishing rod and dropped into deep waters. Then, fishers move the hook up and down to mimic the behaviour of squid. This provokes a Humboldt squid, which starts following the hook. The squid finally attacks the fluorescent bait by wrapping its arms around the needles. At the same time, the imprisoned squid becomes bait for another one. After some repetitions of moving the hook up and down, a whole colony of squids may appear close to the surface.

Humboldt squid eyes look like human eyes. It is an unforgettable experience when, during the cannibalising act, a squid being eaten alive is looking at you. Another thing that entices squids to ascend to the surface is red light. Research states that it stimulates them a lot, but I was not able to observe the effects underwater.

The same techniques used by fishers have been adapted for research and scuba diving purposes. Entry into the water is preceded by time-consuming efforts in the enticement process.

Diving with Humboldt squid is very specific. All activity takes place during the night. When daylight wanes, the whole crew must be ready to start. Nature is very unpredictable in this region, and the risk that the whole expedition ends up with no success is high. So, each day, each attempt, each chance to take a picture is critical, since it may be the last. Bad weather, storms, a full moon may keep the squid in deep waters, laying waste to all our efforts.

The continuous unexplainable migration of the animals increases uncertainty even more. When night comes, divers with cameras need to be ready to go and believe, that out of the batch of photographs taken in very unpleasant conditions —darkness and low visibility—there will be some images good enough to share.

During my trip, we had only one day when diving with Humboldt squid was really possible. All the remaining nights were lost due to bad weather, strong waves or the lack of squid at the surface. Fortunately, that one day was enough to capture a couple of satisfactory shots.

Humboldt squid move very fast. Their flashing, colourful bodies appearing rapidly from nowhere and disappearing even more rapidly into the abyss are like passing missiles. One’s first impression may be an unpleasant one, but the threats seen previously in wildlife films on TV—such as attacks in which the squid remove divers’ masks—did not happen here. During the dive, I did not experience any aggression from the squid. I did not use any protection, and I got no impression that they considered me particularly as food. I saw in their big eyes more a sense of fear or curiosity than a desire to attack me. I am sure I was a more frightening predator to them than they were to me. So, it turns out that Humboldt squid are not demons, devils or killers of humans, proving that the widely accepted stereotypes of these creatures are unfounded.

After this kind of expedition and experience, I often wonder if the media is distorting reality by showing wildlife in misleading ways. Are they producing nature thrillers with the intent of protecting the environment, limiting tourism to these locations, or are they just aiming for an increase in sales and profits? I leave the question open for all to consider. ■