The Battle of Jutland in 1916 was the biggest naval battle in World War I. Over two days of combat, 25 warships were sunk. Undertaking a diving expedition to this isolated place was a real adventure.

Contributed by

Factfile

Having dived over 400 wrecks, Vic Verlinden is an avid, pioneering wreck diver, award-winning underwater photographer and dive guide from Belgium.

His work has been published in dive magazines and technical diving publications in the United States, Russia, France, Germany, Belgium, United Kingdom and the Netherlands.

He is the organiser of tekDive-Europe technical dive show. See: tekdive-europe.com.

Two years before this expedition, I had booked a trip with a team from England to dive the wrecks of Jutland (in the North Sea, near the western coast of Denmark’s Jutland peninsula), but this trip was cancelled at the last moment because the expedition ship’s permit was not in order. It seemed that the papers to go so far out to sea with passengers did not follow regulations.

In 2014, we got a second chance. A dive team from Ghent, Belgium was fully prepared for a trip and looking for more divers to cover the cost of hiring an expedition ship. The intention of the project was to arrange a trip for a group of 30 divers. The 60m long Cdt Fourcault was chosen as the expedition ship. The owner and captain was Dutchman Pim de Rhoodes, and the ship's home port was Antwerp.

I had already done a dive trip to Scapa Flow on this ship in 2006 and knew that she met all the requirements. The expedition ship was also equipped with a decompression tank and a helicopter that could be used in case of an emergency. A seaworthy ship with a good crew is an absolute necessity for a trip such as this one, to open sea, about 90 miles away from the nearest port. The dates for the expedition were set for August 22-29.

Stormy weather expected

About 14 days before departure, a hurricane travelled up the eastern coast of the United States. Across the ocean, this same hurricane also influenced the weather in the North Sea off the western coast of Denmark. With alternating high winds and storms, we worried whether or not we would get better weather for our departure.

Our port of departure was a fishing port of Thyborøn, about 1,000km away from Antwerp. On Thursday, August 21, it was time to go, and we headed off to Denmark, with a stopover in Germany. Cdt Fourcault was already in port, so we could embark immediately. Alas, there were still high winds, so we were forced to stay two more days in the harbour.

On Sunday evening, the weather service predicted a little let-up in weather conditions, so Captain Pim took this opportunity to sail to the distant wrecks. We decided to dive the southern, shallower wrecks first, because the weather forecast was a little better there. On the following days, we visited the deeper, northern wrecks.

Finally... diving the southern wrecks

After a restless night, we looked forward to our first dive and made preparations. The first wreck we visited was the British cruiser, Black Prince.

Black Prince. During the Battle of Jutland, the ship was under heavy bombardment. When its ammunition depot exploded, it caught fire, causing the ship to sink immediately. Today, Black Prince rests at a depth of 47m.

On our dive, visibility on the wreck was about 5m. The weeks of bad weather and storms had, of course, affected visibility underwater. However, it was still a beautiful dive, without any problems.

After our decompression stop, we sped back to Fourcault on a speedy auxiliary motorboat. We were then lifted on board by an elevator.

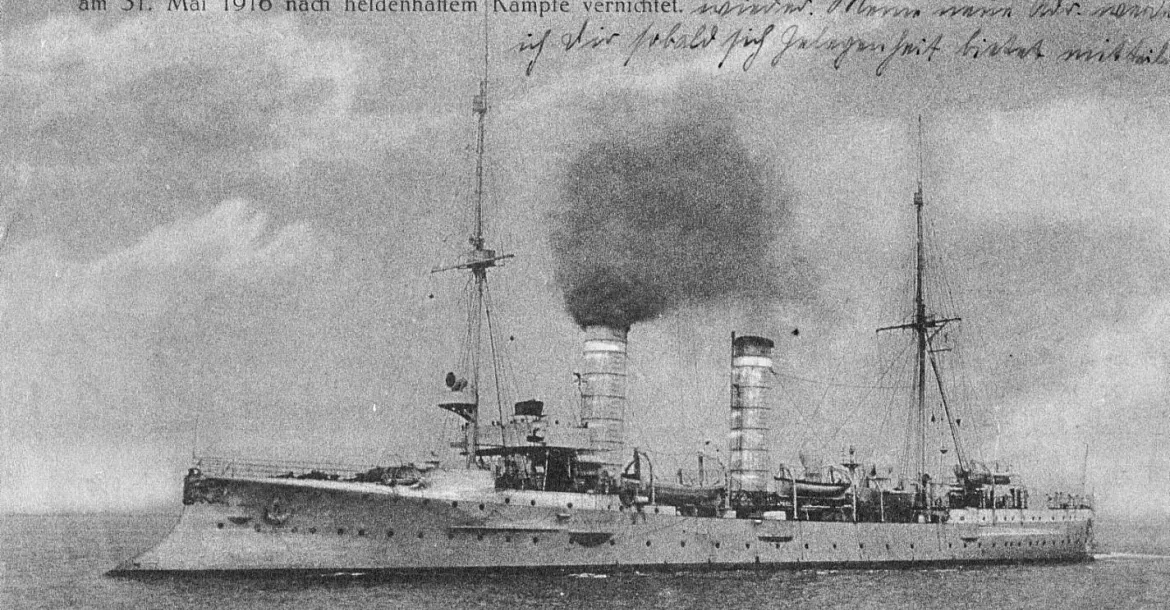

Elbing. Our second wreck of the day was the German light cruiser, Elbing. On good authority from the salvage company, I knew that this wreck was almost as intact as the other wrecks of Jutland. Elbing was quite a large vessel, with a length of 140m and a weight of 4,320 tons.

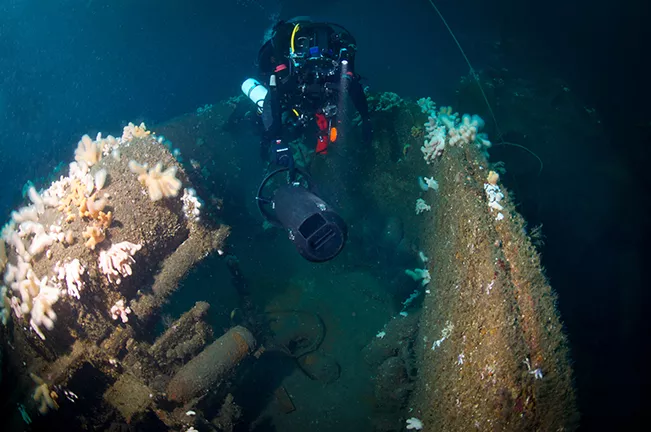

During the descent, we could already see that the visibility was a little better. It was immediately clear that the wreck was in better condition than we had thought. From the widespread scatter of objects on the seabed, it was evident that the wreck had not had a lot of visitors.

We could see portholes all over the wreck. There were also china and glassware resting in different places. During the dive, I saw a big cod swimming past us. These fish have become very rare at the wrecks in my home waters off the Belgian coast. After about 45 minutes, I started my long decompression stop.

Unique discovery

After an excellent dinner, we were briefed on the dives for the next day. Meanwhile, the weather got a lot better, and the forecast for the rest of the week was good too. The goal for the next day was another German light cruiser named Frauenlob.

Frauenlob. The cruiser was built in 1902, with a length of 110m and a weight of 2,700 tons. During the Battle of Jutland, the ship came under fire from the English flagship, Southampton, which was under the command of Commodore William Goodenough.

Almost immediately, Frauenlob was hit by a torpedo from Southampton. The engine room was seriously damaged and the ship submerged completely. It all happened so quickly that none of the 320 crew members survived the disaster.

At the mooring buoy, we followed the descent line to the wreck. When I reached the bottom, my computer indicated a depth of 48m. The visibility was about 5m and the water still had a milky colour. Because I was taking photographs with my camera during the dive, I lost sight of my buddy very quickly.

As on the other wrecks, there were a lot of portholes on this wreck, and I could also distinguish different parts of the steam engine. I also saw a thick iron sheet on the wreck, which had obviously been hit by three shells. At the places where it was hit, the steel was totally bent inwardly.

When I got onto a more even keel, fellow diver Erik Billiau swam along with me. A few moments later, he was violently agitating his lamp. When I swam closer, he signalled toward an object situated in a hole between the sheets of the hull. As I happen to have some antique dive helmets in my possession at home, I immediately recognised the object as a copper Siebe Gorman diver helmet.

The temptation to bring this special object to the surface was strong, but these wrecks are war graves, and as such, are protected and must be treated with respect. So we left the helmet on the wreck. It was, however, curious that the helmet, which was of English workmanship, was found on a German wreck. Of course, it could also be that this wreck was not the Frauenlob, but an English cruiser. I have no idea why the name Frauenlob was linked to this wreck in the past.

The big armoured cruisers

Lutzow. That same day, we also dived to Lutzow. With a weight of 26,000 tons and more than 200m in length, this was the biggest wreck on our list. Of this dive, I will always remember the big cannon laying among the wreckage. It was difficult to estimate, but I think it was about 15m long, with a width of 1m at the thickest part.

Queen Mary. The day after, we made a dive on another giant. Queen Mary is almost as big as Lutzow and rests, as so many of the big battleships do, upside down on the bottom of the sea. This occurs because of the weight of their big cannons. It was also obvious that salvage work had been done on these wrecks.

The northern wrecks

With a calm sea and a radiant sun, we could now move to the northern wrecks. The first wreck we looked for was the Indefatigable.

Indefatigable. This British battle cruiser of about 19,000 tons was, unfortunately, totally in ruins. The salvagers did not achieve their goals here. It was amazing, however, that we had more than 10m visibility on this dive. Due to the breaking up of the wreck, the wreck field became enormous and difficult to survey.

The best for last

HMS Defence. On the last day of the trip, we planned to dive HMS Defence, and everybody was impatient to know what this dive would bring. During my descent, I could already see the wreck 20m under me. Of course, we had ideal circumstances, with calm seas and a lot of sun, so light was able to penetrate at depth.

Beneath me, I saw two powerful motors, still standing up. Farther on, I saw some Yarrow boilers which were still recognisable. The cannons, too, were still standing up. It was an unforgettable sight.

Farther on, we also found the bow, with the anchor windlass and chain. We saw portholes all over the place, and in the bottom of the bore of one of the cannons, there were shells still in place, ready to fire. With a length of 170m, it was a rather large wreck and time flew by.

The second dive of the day was also made on this beautiful wreck. HMS Defence was, for me, the apex of a week of fantastic diving. I cannot wait to go back! ■