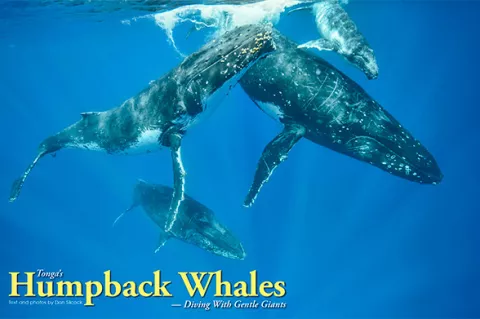

Our skipper, Ali, carefully maneuvered the boat into position and cut the engine, shouting, “Go, go, go!” at the top of his lungs. And go we did—straight into the deep blue water, with cameras held in vice-like death-grips and onto the path of over a dozen mature and rather excited humpback whales.

Contributed by

Factfile

Asia correspondent Don Silcock is based in Sydney, Australia.

He travels widely in Asia and his website (www.indopacificimages.com) has extensive information and image galleries on the great dive locations across the Indo-Pacific region.

Humpback whales average around 14m long and about 35 tons in weight―that’s a lot of mass coming at you―but there was no time to feel scared or even count these huge submarine-like mammals, because we were finally witnessing one of their famed heat runs, when a female humpback has signaled that she is ready to mate and all males in the vicinity come a-running.

For the males, the heat run is the ultimate test of their masculinity and the reason they have traveled over 6,000km from the Antarctic. Only one of them will be chosen to be the one. They will have to out-swim, out-maneuver and outwit the other males in their quest for the female’s favor. It is truly an incredible sight to behold and one that not many people will ever get to see firsthand; the Kingdom of Tonga is among a few select locations globally that allows a limited number of operators to place small groups of people into the water with the humpback whales.

About Tonga

The South Pacific nation of Tonga consists of over 170 islands stretched out across an 800km-long archipelago on the western edge of the Pacific Ocean area known as the Polynesian Triangle. An interesting country with a rich history and very strong culture, Tonga is one of the few places in the world where it is possible to swim with the humpback whales that migrate to Tongan waters every year from their feeding grounds in the Antarctic. Located about 1,600km northeast of New Zealand, the Tongan islands fall into three main groupings that occupy an overall land area of just 750 sq km—scattered across a total area of some 700,000 sq km.

Geologically, Tonga is an interesting mix of the volcanic and non-volcanic. The archipelago aligns roughly north to south and is about 70km across at its widest point. In the south is the Tongatapu Group, which includes the capital of Nuku’alofa (on the main island of Tongatapu) and the remarkable island of ‘Eua to the east. In the middle of the archipelago is the Ha’apai Group and to the north is the Vava’u Group.

Culturally, Tonga is very much Polynesian and the original settlers are believed to be the Austronesian Lapita people of Southeast Asia. The Lapita settled in the islands of what are now the independent countries of Tonga, Samoa and Fiji, somewhere around 3000 B.C. According to oral history, around 950 A.D., the Tu’i Tongan Empire first emerged, which reached its zenith in the 12th century, stretching some 9,500km across the Pacific Ocean from the tip of the Solomon Islands in the west to Easter Island in the east.

The expansion of the Tu’i Tongan Empire was enabled by their long-distance kalia double-canoes, which established the Tongans as the most advanced shipbuilders in Polynesia. These ocean-going vessels, with their big and distinctive triangular sails, reached lengths of over 25m. They were capable of carrying 200 warriors each, at speeds of up to 11 knots across huge expanses of the Pacific. Numerous wars, internal dissent, assassinations and tyrannical rulers saw the Tu’i Tonga Empire slide into serious decline in the 14th century. By the 16th century, the party was over.

Unique among Pacific nations, Tonga has never completely lost its indigenous governance, and the islands of the Tongan archipelago were united into a Polynesian kingdom in 1845. Tonga became a constitutional monarchy in 1875 and a British protectorate in 1900. Then, in 1970, it withdrew from the protectorate and joined the Commonwealth of Nations. Tonga remains the only monarchy in the Pacific.

The humpback whales are present in Tongan waters from around mid-June to early October and can be seen all over Tonga, but the Vava’u group of islands in the north of the archipelago is by far the most popular area to see them.

The cycle of life

Each winter, the humpback whales visit Tonga in a cycle of life characterized by a remarkable annual migration north from their feeding grounds in the Antarctic to the 170-plus islands of the Tongan archipelago where they breed and give birth. The whales of the Tongan tribe are but a small part of the estimated 60,000 whales that make up the current southern hemisphere humpback population.

Incredibly, that population had been reduced to less than 5,000 by the time commercial whaling was formally banned in 1986—taking the humpbacks of the southern hemisphere to the very brink of extinction. Whaling was so devastating because humpbacks are creatures of habit. Those in the southern hemisphere return to the same feeding grounds around the polar ice-cap every summer to gorge on the huge schools of krill that abound there. Then, come May, as winter starts to descend upon the Antarctic, they migrate north to their mating and breeding grounds using the same migratory corridors.

A similar pattern is repeated across all of the independent but co-existent groups that make up the southern population. As the Tongan tribe—as it is often referred to—starts its journey north, so do the much larger eastern and western Australian, South American, South African and Hawaiian groups. For the whalers, as the Americans would say, this was like shooting catfish in a barrel. Not only did the whalers target the humpbacks in their feeding grounds and migratory corridors, they also hit them in their breeding grounds by taking advantage of the strong bond between the fast-moving, deep-diving, slow-breathing mothers and their surface-bound calves that need to breathe every few minutes—simply put, catfish in a barrel.

Recovery and the impact of tourism

Nature has an incredible potential to heal when we allow it to do so, and the recovery of the southern and northern hemisphere humpback populations (which incidentally never meet, because of the polar-opposite nature of the seasons) is testament to that ability. Recent appraisals have put the global humpback population at around 100,000, which is 80 percent of the pre-whaling estimate of 125,000. The recovery has generally been so strong that some 45 years after they were formally protected under the federal Endangered Species Act, the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) is proposing the removal of most of the global population groupings from the endangered species list.

In Tonga, although the humpback population has recovered, it is well below the 80 percent global average. Current estimates put the Tongan tribe at around 1,000 whales in total—some 50 percent of the pre-whaling guesstimate. The Tongan tribe was one of the last to be hunted by the commercial whalers (there were richer pickings elsewhere) and also suffered from the disproportionate impact of the country’s domestic whaling industry.

Although small-scale and semi-traditional in nature, the Tongan whalers used large canoes and handheld harpoons to hunt humpbacks. Their only way to harvest the meat, oil and bones of the captured whale was to tow it back to shore. Practically, this meant that the only whales which they stood a chance of killing were the small two- to three-ton calves; because if they harpooned a large humpback, they would be the one being towed—probably far out to sea!

Already suffering badly from the commercial whalers, hunting the calves had a double-whammy impact on the already critically small numbers of the Tongan tribe, a situation that was tacitly acknowledged when the King of Tonga formally banned whaling completely in 1978—eight years before the rest of the world did. The decision was unpopular at the time, but given the rebound in the numbers of the Tongan tribe from their 1978 low of around 250 whales and the significant impact of whale-watching on the domestic economy, there is little doubt that the decision was a very wise and far-sighted one. It has been estimated that a single humpback whale returning to Tonga every year could generate US$1 million in whale-watching revenue over the course of its 45-year lifetime, leaving little doubt that a live whale is considerably more valuable than a dead one.

Mothers and their calves

The annual migration of the Tongan tribe covers a journey of over 6,000km from their feeding grounds in the Antarctic to the warm waters of the archipelago. Traveling at an average speed of around 6km per hour, they rest sparingly and live off the fat reserves they have built up during the summer months in the south.

Their migration path takes them up the eastern coast of New Zealand and along the sub-sea volcanic arch that forms the bedrock for the Tongan archipelago. They make that epic journey to mate and so that the females, pregnant from the previous year, can give birth in the warm waters and relative safety of the many sheltered bays of the archipelago. Those bays are also the perfect nurseries where the mothers can nurse the calves on their rich milk so that they can quickly bulk-up in preparation for the long journey to the Antarctic feeding grounds.

Encounters with a mother and calf are a special and very touching part of being allowed in the water with the Tongan humpbacks, but they have to be done carefully as the mothers are extremely protective and wary of potential predators. Under the whale-watching guidelines established by the Tongan government, there is a 300m radius exclusion zone around the humpbacks that vessels must not enter; however, licensed operators may enter what is called the caution zone which allows them to get as close as 100m. Entry into the water has to be done silently outside that 100m boundary; otherwise, the mother, sensing possible danger, will lead the calf away. A maximum of four swimmers, plus a guide, are allowed to enter the water and approach the whales. This must be done very quietly (no splashing fins) and carefully so as not to intimidate and scare them away.

A good guide can read the body language of the resting mother and will position the group so as to maximize the interaction and photographic potential. If the mother has accepted the presence of the swimmers, the encounter becomes sublime as she may even approach to take a closer look; being so close to such a huge creature is an experience that stays with you forever.

The heat run

If the mother-and-calf encounter is a gentle and calm experience, the heat run is almost the complete opposite as you are dropped some 100m upstream of the pack of cavorting males chasing the lone female. They are moving fast and your time is very limited as they rush towards your direction, intent on securing their part in the evolution of the species. It truly is an awe-inspiring sight, as the female leads the way and the males compete to stay in the race by charging one another to try and knock a competitor out, or diving below another male to blow a bubble curtain to disorientate him so that he drops out.

Incredibly, despite their seemingly intense focus on procreation, they seem to know where you are and avoid you, which is pretty reassuring given the potential impact a 35-ton creature traveling at speeds of up to 10 knots could have on the human frame. Heat runs can go on for hours, so it is quite possible to have multiple encounters by being picked up and then dropped in again in front of the pack.

Singers

Although they have no vocal chords, male humpbacks can produce complex songs by somehow circulating air through the various tubes and chambers of their respiratory system. The singing is believed to play a part in the breeding cycle, and singing males position themselves vertically in the water with their flukes up and heads down when performing. Often, this is quite close to the surface; and as they remain static in this position, it is possible to duck-dive down to get a closer look without disturbing the whales, which appear to be in an almost Zen-like state. However, when heard underwater, the sound waves produced during the singing make your whole body vibrate, so getting close to a performing male is an intense and somewhat intimidating experience.

Swim-pasts

Swim-pasts are dives in which you have been dropped ahead of a traveling pod of whales and they swim past you. There are two types of swim-pasts: those with a group of young males who appear to be hanging out together (a bit like the human equivalents you see at large shopping malls) and then there are the mothers and calves together with their escort.

Escorts are mature male or female humpbacks that tag along with the mother and calf and help fend off predators and males which may try to force their attention on the mother. If the escort is a male, his motivation is rarely altruistic, as he would be hoping to be allowed to mate with the mother. It is not known why females take up the escort role, but the answer probably lies in the social nature of the humpbacks.

Similar to the heat run encounters, swim-pasts do not last long, but they typically are not repeatable, since the traveling whales will dive down, if they are approached too much.

Playful calves

Newly born calves are three to four meters long, weigh up to one ton, and are formidable animals in their own right (though they appear small when swimming beside to their mothers). Initially, they are quite timid, and the mothers are very protective. Nevertheless, consuming up to 200 liters of their mothers’ fat-rich milk every day allows the calves to grow quickly. As they do, they start to demonstrate playful behavior at the surface such as breaching and tail-slapping. It is believed that this strengthens the calf in preparation for the long migration southwards; hence, the mother will permit this cavorting around while watching out for potential predators.

The calves are very inquisitive and may come over to check you out, but be warned this is probably as dangerous as in-water whale-watching gets. Although not aggressive in nature, the calves have very little spatial awareness, unlike the mature whales that always seem to know exactly where you are. So you may get side-swiped by the calf’s pectoral fin or fluke as it turns, or, even worse, get caught in a tail-slap! In my opinion, the risk is well worth it as the interaction with the calves is a sheer delight, as their youthful energy and enthusiasm seems to positively radiate from them, making such encounters truly memorable.

Afterthoughts

I spent almost three weeks in Tonga, based in Neiafu, the capital of the northern Vava’u group of islands, which is the main whale-watching area of Tonga. Apart from Sundays, when everything apart from the many churches are closed by royal decree, I was out on the water virtually every day from about 8:00 a.m. onwards.

Each day was different in some way or another—one day we would have great mother-and-calf interactions, other days would be filled with swim-pasts, while yet others would have playful calves or singers.

Then, there was the day with the incredible heat run. But as we came back into Neiafu’s beautiful Port of Refuge harbor in the late afternoon, I was always filled with the same sense of wonder and awe at what we had experienced earlier that day in the water with these magnificent creatures—a truly unique experience! ■