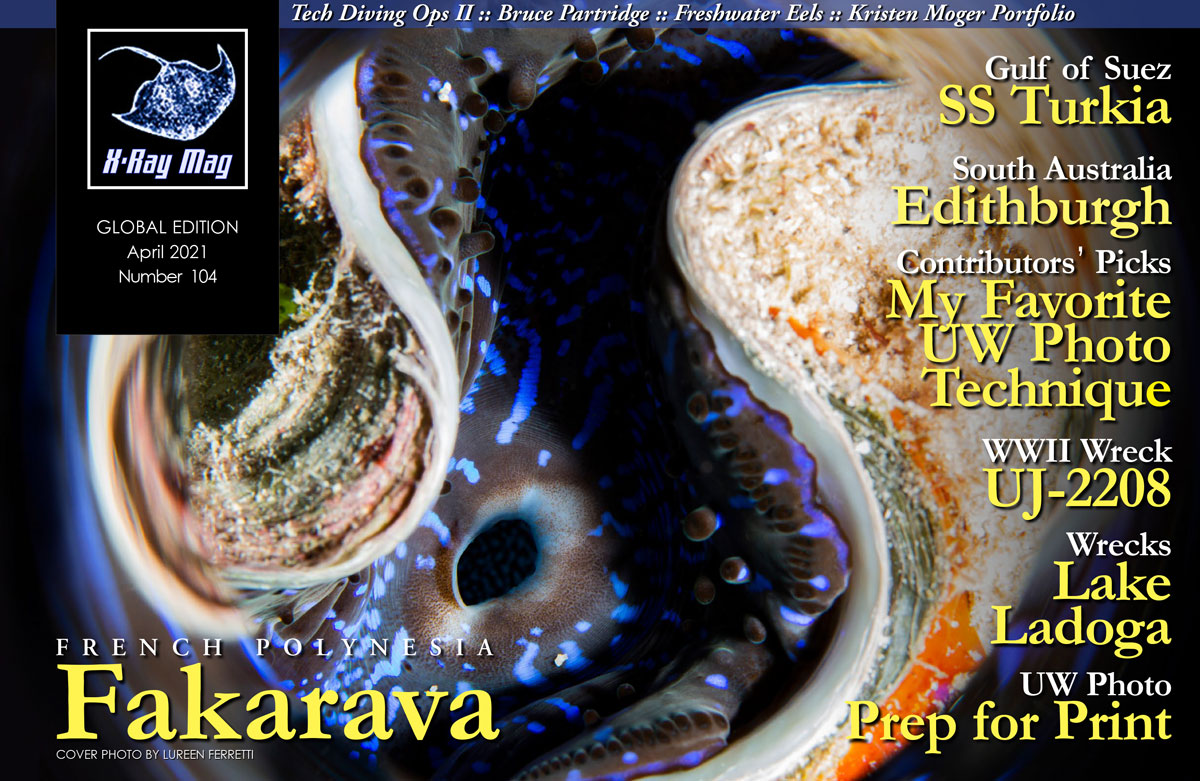

Fakarava is an atoll in the Tuamotu archipelago located about 440km northeast of Tahiti in French Polynesia. Pierre Constant takes us on a journey to the pristine lagoons of Tuamotu and describes what awaits adventurous divers in its underwater realm.

Contributed by

The wooden dive boat was at anchor in the Koh Prins Islands, south of Koh Rong. Turquoise blue was the lagoon at midday, an idyllic image of paradise. All of a sudden, someone shouted: “Whale shark!” The next minute, Sebastien jumped overboard with mask, fins and snorkel, chasing the poor creature with his GoPro action camera. It was his first whale shark, ever. Amused, I watched from the upper deck, with a smile on my face, as other people were already in tow. There was no need to join the frantic club.

This occurred once upon a time in Cambodia, back in 2012. Sebastien and Sophyline were a French-Cambodian couple I knew at the time. By a trick of fate, I met them again seven years later on Fakarava Island, in the Tuamotu Islands of French Polynesia. Water has passed under the bridge since the last time I had seen them. Their story was that of an unexpected dream come true—a drastic change of life.

Sebastien had first worked as a maître d’hôtel (butler) for nine years in restaurants and luxury hotels of the French Riviera. Changing jobs later on to work in computers as a programmer and analyst, he was employed by BNP Paribas Bank and became a project manager. His path crossed that of Sophyline in 2009, who also worked for the same bank in marketing and communications. They got married. In 2014, they moved to Switzerland to work for the same bank. On the side, they both became divemasters and PADI Instructors, teaching in dive clubs after hours.

Further on, they led various missions for the civic and social organisation company Plongeurs du Monde (Divers of the World) to train young people to becomes divers in Sri Lanka. Sophyline became the head of the dive division of BNP Paribas for the following five years, responsible for communications, organisation of trips and budget management. Sophyline’s 40th birthday was the occasion for a trip to French Polynesia. The idea of a change of life emerged. Why not work as divemasters?

They got in touch with Dive Spirit Fakarava during a transition period in 2018. Owned by a Spanish-French couple, the dive centre had been sold to new owners based in Moorea. Fortunate to meet the new and old owners, as well as the managers, Sebastien and Sophyline submitted their resumes just in case anything turned up. That caught the attention of the new owners, who realised the potential of the couple’s professional skills. A few months later, as the managers resigned, Sebastien and Sophyline were offered the positions to run and manage Dive Spirit Fakarava. They moved to the Tuamotu in June 2019 to start a new life.

History and geology

Although Ferdinand de Magellan was the first European to sail by the Tuamotu Islands in 1521, it was the Russian navigator Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen who was credited with the official discovery of the archipelago in 1820. Frenchman Jules Dumont d’Urville visited the islands with his ship in 1838.

Fakarava is an atoll of the Tuamotu archipelago, located 16°18’ S and 145°36’ W. It lies about 440km to the northeast of Tahiti. Fakarava seamount—an ancient volcanic island, now submerged, rising 1,170m from the seafloor—is crowned by a barrier reef in a rectangular shape, oriented northwest to southeast. One of the 76 atolls of Tuamotu, Fakarava’s lagoon—which is 60km long by 21km wide—has a surface area of 1,121 sq km and two passes: Ngaruae to the northwest and Tumakohua to the southeast.

Rotoava, the main village has a population of about 850. Shaped like a boomerang, the island’s only road stretches 20km to the southeast and 11km to the northwest, passing by the airport. To reach Tetamanu village at the South Pass, one has to catch a boat for a one-hour ride, depending on surface conditions.

Fakarava’s old name is Havaiki-te-araro (the fabled original homeland of the Polynesians). The atoll was declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1977, to collaborate with the indigenous population in preserving the environment, alongside economic and social development (environment.fr).

Getting there

Air Tahiti’s one-hour flight from Papeete to Rangiroa was followed by a 40-minute flight to Fakarava, where I landed mid-afternoon. Sophyline and Sebastien greeted me upon arrival. It was an 8km drive to Dive Spirit, which was conveniently located right on the lagoon. Two restaurants, locally known as “snacks,” could be found nearby.

Still affected by a 12-hour jetlag from France, I waited a day before I went out diving. It gave me time to leisurely prepare equipment and my underwater camera, and to enjoy a bicycle ride around the village. Covered by vegetation, Casuarina trees and coconut trees, the island’s ribbon-like land mass was barely 200m wide, from outer reef ocean-side to lagoon-side. The scent of frangipani and tiaré flowers permeated the air exquisitely.

Early in the morning, the lagoon lay in mist and it rained slightly. “It’s nothing!” joked Carlos, one of the sturdily built Polynesian boat captains. Indeed, it stopped before 7:00 a.m. Dive Spirit had two hard-hull inflatable boats powered by twin 150hp outboards. The “Red Boat” was 8m long with capacity for eight divers, and the “Grey Boat” was 6m long with capacity for five divers.

Ngaruae

We departed at 8:00 a.m. for Ngaruae—the Passe Nord in French or northern channel—20 minutes away. With a width of 1.6km, it was by far the largest in Polynesia.

“There is incoming tide,” explained the dive guide during his briefing. Nevertheless, the current can be erratic, with countercurrent and transversal water movements as well. The French rules are very strict when it comes to diving; Sebastien made sure that everyone understood the dive plan clearly, especially at the safety stop, before surfacing all together. “I want you to make a chain behind me, holding each other’s tanks,” he said, “as the captain will zoom in on me, holding the safety sausage well in evidence.” In the channel, the tidal bore or mascaret in French—when the wind hits the current—can be quite strong and the surface waves can be wild.

With the water being 27°C, I dived without a wetsuit, although it felt slightly cool but bearable. There were plenty of small grey reef sharks, around one metre long, cruising by, as well as a school of barracudas in the blue. But the highlight for me was a group of three African pompanos (Alectis ciliaris), which were silver and had a diamond shape, with threadlike extensions in the dorsal and ventral fins.

Feeling a bit cold at the end of the dive, I donned a 5mm shorty to be comfortable and kept it on until the end of my stay! Fifteen-litre steel tanks were used daily. On the next dive, I noticed the common schools of fish on top of the reef; Paddletail snappers (Lutjanus gibbus) were very tame, unlike those in most of Southeast Asia, and could be approached for wide-angle shots. Long-nosed emperors, parrotfish, red snappers, Napoleon wrasse, unicornfish and pyramid butterflyfish were regular sightings. Massive in size, the coral reef was monotonous in colour, greyish white overall, with numerous dark green to black sponges. Gorgonians, soft corals and sea fans were conspicuously absent. Hard corals included Acropora, Montipora, Porites, Pocillopora and Millepora species as well as the solitary Fungia coral.

On subsequent dives at Ngaruae, a couple of mantas appeared at a depth of 40m. One was dorsally black and white, which was the female, and the other one was dorsally black with white underparts, which was a male in hot pursuit of the female. Large dogtooth tunas cruised by in a hurry, and lone great barracudas foraged on top of the reef.

Ali Baba. One morning, we dived the site of Ali Baba, which was located well into the channel. It was a drift dive, in which one follows a canyon, with pockets of calm waters. There were impressive streams of yellowmask surgeonfish (Acanthurus mata) as well as large schools of one-spot snappers, (Lutjanus monostigma) and tight groups of bigeyes (Priacanthus hamrur), crimson red in colour. Schools of barred unicornfish (Naso thynnoides) could be seen at times. With clear visibility, cobalt blue waters and the sun on the surface, it was a photographer’s delight!

Day Three

The sky was really dark when I strolled down the wooden jetty at 5:30 a.m. The Red Boat was the only touch of colour against the dark turquoise blue of the lagoon. One hour later, it poured down heavily. “It should rain all day long,” lamented Sebastien, “probably most of the week, according to the weather forecast.” Eventually, diving was cancelled. Security and safety first, is Dive Spirit’s motto.

A walk along the ocean side gave me a chance to see the bird life of the atoll. Seabirds spotted included the greater crested tern (Thalasseus bergii), with a yellow bill and black cap; the white tern (Gygis alba); the black noddy tern (Anous minutus); and the grey-backed tern (Sterna lunata). A brown booby (Sula leucogaster) flew by occasionally. Greyish blue reef herons and common egrets added to the picture.

“Ia Orana!” greeted Captain François of the Red Boat, looking very much like a pirate with his goat-like beard. “Today, Maï taï!” (All is well) he beamed, referring to the good weather. Our luck manifested itself in the presence of a school of spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris) soon after we entered the water. It was a chance to get a couple of shots of them, albeit not too close. Exhilarating!

At one point in the dive, a lone manta came face-to-face with a group of divers hanging onto a coral slope. Indecisive about flying above the intimidating curtain of bubbles rising from the divers, it turned around with a Zen-like attitude. Adding to the excitement, during our surface interval, an inquisitive humpback whale came breaching between the boats. With a final loud grunting noise, it displayed its flukes, upon diving into the deep.

Passe Sud

With the arrival of the weekend, the conditions turned good, even perfect for the Passe Sud, or southern channel. It took one hour to reach the village of Tetamanu, at the southern channel of Tumakohua, where a dive centre and a few bungalows could be found. The site was very exotic, postcard ideal, with a chain of motus (islets), and white sandy beaches crested with coconut trees.

The channel itself was not really wide, and we waited for the incoming current to dive at the entrance of it, on the ocean side. The show here was a so-called “wall of sharks,” which in fact was not a compact wall, as one would think, but rather a steady stream of grey reef sharks swimming upcurrent in a leisurely manner. Divers were expected to cling to the coral reef at a depth of 20m, stay put and watch the performance, so that everybody could see the sharks. The maximum depth of the channel was 31m, but we started at 13m, and gradually drifted downstream.

Blacktip and whitetip reef sharks passed by together. I came across a small school of blue trevally (Carangoïdes ferdau), with bars across their sides, over the white sand—aka the “Ski Slope”—and a rather shy scrawled filefish, which was pale green with blue dots and streaks. A school of blue and gold bluestripe snappers (Lutjanus kasmira) was an unexpected surprise against the reef slope.

Towards the end of the dive, we drifted under the pontoon of the village, a refuge for a massive group of one-spot snappers, paddletail snappers and the odd Napoleon wrasse. It was great for wide-angle shots, with the pier pilings and the sun rays in the background.

Our lunch break took place on a tiny paradisiacal motu named Sables Roses for its pink sands. Polynesian raw fish in coconut milk, fish fritters and rice made up the meal—just perfect! The lagoon environment was enchanting, and the light breeze in the coconut fronds was most welcome.

On the second day of diving at Passe Sud, Sophyline accompanied me as a personal guide. It was slack tide. We waited for a while at a depth of 30m to gaze at the virtual screen of sharks, more numerous than ever. I caught a glimpse of four passing silvertip sharks (Carcharhinus albimarginatus), or tapete in Polynesian, on which all the fins were white-tipped. Sadly, they were just too shy for me to take a close shot.

We left our observational balcony to avoid decompression time and entered the shallows of the channel, with the reef slope on our right. “Well, there is nothing else to see,” I thought to myself. Then Sophyline caught my attention, frantically pointing to something big behind me. Pivoting 180 degrees, I stared bewildered at a juvenile whale shark, with literally a swarm of grey reef sharks in tow, like a bride’s veil, following the giant. I managed a furtive shot before it vanished lethargically into the blue. “The sharks are just waiting for it to get sick or tired; then they will hunt and go in for the kill, like a pack of wolves,” confirmed Teddy, our other dive guide, who proudly displayed an octopus tattoo on his right arm. It was a breathtaking image to remember.

Traditions

I wondered about the conspicuous absence of sea turtles (tifai in Polynesian). When I asked Captain François about it, he confessed: “Now that they are protected by law, there is a lot of poaching… In the past, the elders used to collect and rescue baby turtles out of their nests; on hatching day, they brought them to enclosures. Then, they distributed them to villagers, who would breed the hatchlings for a few months in their homes,” to then be released in open water. This was their way of managing resources for the future. “You see, eating turtles is a part of our customs, especially on festive occasions.”

Elda, the owner of the “snack” of the same name, where I ate dinner almost daily, also explained that Polynesians ate the raw meat of blacktip sharks. “It has long been a tradition at weddings.”

Afterthoughts

Fakarava, with its clear blue waters, is one of the 76 atolls of the Tuamotu, where anything can happen at any time. The name “Tuamotu” comes from the Polynesian word tua, which means “maritime space,” and motu, which means “a speck of detached land” or “islet.” In such a vast expanse of water, such as the Pacific, be prepared for the unexpected. You might fall under its spell. ■

With a background in biology and geology, French author, cave diver, naturalist guide and tour operator Pierre Constant is a widely published photojournalist and underwater photographer. For more information, please visit: calaolifestyle.com.