Ever since the release of the Lord of the Rings, New Zealand has been synonymous with Middle-earth—a South Pacific wonderland of forests, mountains, volcanoes and geysers featured in the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit trilogies. Although revered for its topside beauty, New Zealand remains somewhat obscure as a diving destination. Yet, the North Island is home to a place Jacques Cousteau considered one of the world’s top ten diving locations—the Poor Knights Islands.

Contributed by

Situated off the Tutukaka Coast, a three-hour drive north of Auckland, the islands have long been on my radar. Featured in documentaries, including BBC’s original Planet Earth series, they have captivated me from the get-go. From the reefs to the fish life, everything was unfamiliar and exciting. Additional research revealed the nearby Bay of Islands had some intriguing wrecks. After years of tropical diving, I was hankering for something new. Considering my previous trip to New Zealand was 30 years ago, a return visit was long overdue.

Auckland

My first three days would be spent visiting friends in Auckland, after which I would drive up to Tutukaka and the Bay of Islands for the remaining six days. Fortunately, the trip proved much easier the second time around. From Toronto, it was a five-hour flight to Los Angeles, followed by a 12-hour flight to Auckland on Air New Zealand. The two-bag allowance was a godsend, especially with all my underwater camera gear. I arrived on a beautiful late summer day, a vast improvement over the winter I left behind.

The first day was a rest day, catching up on old times accompanied by numerous cups of coffee. I also arranged my rental car for the drive up to Tutukaka. Surprisingly, I had no jet lag. Perhaps it was due to leaving at 10:00 p.m. and arriving just before 7:00 a.m. (it was an entire day ahead, though) or maybe it was just the coffee. Regardless, I managed to sleep the entire night and woke up refreshed. A real first!

Having missed Auckland the first time around, I was eager to explore New Zealand’s biggest city. Nestled between twin harbors and punctuated with volcanoes (some dormant), Auckland is certainly blessed in the scenic department. Home to the world’s largest urban Polynesian population, the skyline is dominated by the Sky Tower—at 328m, the tallest structure in the Southern Hemisphere.

After parking, we headed for the waterfront, the city’s traditional front door. Occupying a prominent location was the Ferry Building, resplendent in yellow Edwardian Baroque. Completed in 1912, it is a hub for the Auckland ferry network that connects the city with North Shore suburbs, west and south Auckland, and nearby islands.

Devonport. From here, we caught a ferry to Devonport, located to the north across Waitemata Harbor. A mere 12-minute journey, it soon proved a world away from the downtown’s urban bustle. Enjoying a relaxed seaside village vibe, it is renowned for its beaches and restored Victorian and art deco buildings. After some exploration, we stopped for a gelato, which I suspected was a national obsession based on the number of shops serving it.

Viaduct Harbor. Back in Auckland, we strolled over to Viaduct Harbor. A residential, commercial and entertainment district on the waterfront, it is home to over 30 bars and restaurants as well as New Zealand’s Voyager Maritime Museum. The marina was home to some seriously impressive cruisers and yachts—not surprising, as Auckland is called “The City of Sails.” It could also be called “The City of Shipping Containers,” as it has found plenty of creative uses for them, from fish and chip shops to public lavatories. My favorite rendition was a pair of containers converted into open-sided mini-libraries.

One Tree Hill. The next day, we ventured to One Tree Hill, Auckland’s second highest volcanic peak at a height of 182m and home to some controversy. Once a massive pā (fortified village) that was home to several thousand people, it was named for the lone tōtara tree that once stood at the summit. Felled by a white settler in 1852, a radiata pine was planted in the 1870s to replace it, after repeated failed attempts to grow native trees.

The tree was attacked twice by Māori activists, first in 1994 and again in 2000. Irreversibly damaged, it was finally removed due to risk of collapse. In 2016, nine tōtara and pohutukawa saplings were planted and remain well-protected. Ascending sheep-laden hills to the summit, the views were superb, extending from the city to the Tasman Sea and Pacific.

Driving

Finally, the moment of truth had arrived: D-Day (driving day). I was apprehensive as it had been many years since my last left-side drive excursion. With my tiny Toyota Corolla packed, I was off! Driving proved easier than expected, and once over the Auckland Harbor Bridge, traffic lightened considerably. Outside Auckland, the highway became a toll road, which turned out to be the shortest I had ever seen. Upon exiting a tunnel, that was it for the toll road—more meters than kilometers. There wasn’t a toll booth, but the NZ$2.00 fee can be paid online, with a five-day payment window.

About an hour north of Auckland was a sight I remembered from my first trip: SheepWorld! A sheep-themed tourist attraction, my friends and I thought it was the funniest thing ever (well, we were in our 20s) and stopped to photograph the sign. I thought it fitting to stop for an updated photo and grab a coffee. However, there was something I did not expect—pink sheep! (No, I had not been drinking). Park staff originally dyed the 60-strong flock pink for breast cancer awareness week, but it proved such a hit with visitors, it was maintained as a permanent fixture. Actually, the sheep appeared red, but maybe it was due to the rain.

I also frequently encountered the squashed remnants of New Zealand’s most hated animal: the common brushtail possum. Introduced from Australia in the 1850s by European settlers to establish a fur trade, the marsupials proved catastrophic, chomping through native vegetation and native birds’ eggs and chicks. With no predators, numbers skyrocketed, peaking at around 60 million by the 1980s. Stringent control measures have reduced numbers to a mere 30 million. Still, with only four million human residents, the possums could stage a coup.

Tutukaka

Just north of Whangerei, I reached my turnoff and soon arrived at the pleasant seaside town of Tutukaka. Despite the town’s compact size, the marina was huge, being a major departure point for both dive and sport fishing excursions, with black marlin particularly sought after. I promptly found Dive Tutukaka and stopped in to say hello. The shop was quite striking, like a cave interior hewn from solid rock. I was warmly greeted by co-owner Kate Malcom, who runs the shop with partner Jeroen Jongejans.

Dive Tutukaka is New Zealand’s largest dive charter company, with five vessels that take over 12,000 people to the Poor Knights Islands annually. Although daily trips are offered year-round, I would be doing things a little differently—courtesy of the Acheron, their 24m liveaboard. Equipped with four twin-share en-suite cabins and one twin-share cabin, our trip would cover three days and two nights, with three to four dives daily.

I then headed to the equipment counter to organize gear. A 7mm suit is standard, along with an underlying vest with attached hood. While getting sorted, I glanced over to the “Sightings of Cool Stuff” board and my jaw dropped. Sightings that week included giant kingfish, Bryde’s whale, pregnant eagle ray, hammerhead, seven-gill and bronze whaler sharks, mola mola and manta rays. Kate then showed me a video of the latter—a 6m behemoth encountered the previous day. I wanted to leave that very second!

Afterwards, I headed to my room, located in their newly-opened accommodation adjoining the dive center. It was quite a big operation. Especially impressive was the training pool, raised above ground level with large windows on the sides. By 4:00 p.m., the dayboats returned and I finally caught up with Jeroen, whom I had previously met at a few DEMA dive shows. Although born in the Netherlands, Jeroen is a true Kiwi, having run dive operations on the Tutukaka Coast for nearly 30 years. I was pleased to discover he would be joining us on the Acheron.

With a few hours before dinner, I opted for some hiking in the nearby Matapouri. Parking near the beach, a marked trail led to the nearby headland. Ascending to the top, the views were spectacular. Rugged cliffs dropped to the sea, while in the distance, I could just discern a few craggy islets of the Poor Knights. Inland, the green hillsides were straight out of Middle-earth. I half-expected Bilbo and company to pass by. However, the best was yet to come. Further along was a glorious vista straight from a postcard. Lapped by turquoise waters and fringed with pohutukawa trees, Whale Bay’s talcum-powder beach was one of the most idyllic spots I have ever seen.

Poor Knights

After breakfast, I grabbed my gear and headed to the jetty for the 9:30 a.m. departure. En route, I met the crew and fellow divers. The former included my dive buddy Cameron Barton, another underwater photographer, cook Mandy, instructor Ashleigh McKenzie, Skipper Kevin Delonge and Jeroen. My fellow divers included Dan and Deb from the United States and Andrew, a UK native living in New Zealand. With only four guests, we each got our own cabin. With roughly an hour to the site, we all prepared for the first dive.

Perched on the cusp of the continental shelf 23km from Tutukaka, Poor Knights is an archipelago of two primary islands, Aorangi and Tawhiti Rahi, along with a multitude of smaller islets. Encompassing an area of just over 200 hectares, they were created ten million years ago by a series of eruptions from a massive volcano 25km in diameter and 1,000m high.

Precipitous cliffs plunge up to 100m below sea level, creating an aquatic wonderland of caverns, sea caves and arches. Here, cool water merges with the warm East Auckland Current, fashioning a marine melting pot where subtropical endemics mingle with tropical exotics. Approximately 60 dive sites are found throughout the islands, playing host to over 125 fish species.

Protected as the Poor Knights Islands Marine Reserve since 1981, it extends 800m out from all parts of the islands, associated islets, rocks and stacks. In 1998, full protection was established over the entire area, with access restricted. The islands have been uninhabited since the 1800s, when invaders from the mainland massacred the resident Māori population. Today, access is restricted to purposes of scientific studies only.

Ecologically separate from the mainland for about two million years, the islands are a vital sanctuary for some of New Zealand’s endangered flora and fauna. This is the realm of insects, reptiles and birds, which flourish in the absence of introduced predators. Notable residents include the tuatara, an ancient reptile species predating the dinosaurs, geckos, 25cm centipedes and giant crickets called wetas. Bird species include bellbirds, red-crowned parakeets, New Zealand shags (cormorants), Australasian gannets and 200,000 pairs of Buller's shearwaters. During the winter months, New Zealand fur seals visit the islands.

Discovered by Captain Cook on 25 November 1769 (is there any place in the South Pacific he did not discover?), the name’s origins are open to debate. Cook purportedly named them after poor knight’s pudding (French toast). At the time, pohutukawa trees were shrouded with red blossoms and the islands resembled his favorite dessert covered with jam. Another source claims they resemble effigies of crusader knights lying down. Jeroen indicated one island he said looks like either a chicken sitting on a nest, a cowboy riding a bullfrog or a naked lady lying down. Personally, I prefer his interpretation.

Diving

Northern Arch. Our first stop was Northern Arch, positioned at the northern end of Tawhiti Rahi island and famous for the large numbers of stingrays that congregate during the summer months. Despite being a bit of a cold-water wuss, I could not wait to get in. I was especially eager to try out my brand new Seacam housing for my Nikon D810. Only one other boat was in sight and it was from Dive Tutukaka.

Entering via giant stride, the water was 21°C but the 7mm suit kept me toasty and gloves were not even necessary. Although a bit of a surface swim to the wall, conditions were superb with no current. Visibility was around 25m but was a veritable salp soup, with vast numbers of the planktonic tunicates pulsing through the open water.

Our descent revealed a marine environment unlike anything I had seen before. Brown algae shrouded the walls, along with sea plumes and strap kelp as yellowtail kingfish over a meter long hovered outside the arch. Until now, I knew kingfish as giant trevally in the tropics, but these streamlined titans were entirely new.

Entering the arch revealed a new array of wonders. Clouds of demoiselles and blue maomao cascaded down the walls along with schools of porae or blue morwong, creating a dazzling symphony in blue. I was immediately struck by the tameness of the fish. Even with my 16-35mm lens, my camera’s 36MP sensor allowed frame-filling portraits, even of nudibranchs. It ended up being my primary setup for the remainder of the trip.

Although no ray formations were present, a few huge short-tail stingrays glided near the bottom. Also called the smooth stingray, it is the world’s largest, growing upwards of 2.1m across and weighing up to 350kg. Longtail stingrays and eagle rays are also frequently encountered, the latter looking nothing like their tropical cousins.

Although the arch descended 40m to the bottom, we did not go below 28m. While the cave floor was barren, the walls were ablaze, bursting with sponges, bryozoans, hydroids and miniscule common anemones, their delicate bases striped green and white. Soft, hard and gorgonian corals were also present but on a compact scale. Gawping with wonderment, everything was new and exciting and I did not want the dive to end.

Back on board, Mandy had lunch waiting: a pair of delectable-looking quiches alongside some equally enticing salads. Delicious and healthy to boot. Mandy proved to be a wonder, crafting culinary marvels from the tiny galley, from entire roast chickens to freshly baked pies and hot cross buns.

Middle Arch. Our second dive was Middle Arch, also on Tawhiti Rahi. Descending from 10-20m, it was shallower than Northern Arch but equally enthralling. Gray pillow sponges sprawled across the reef, along with tiny Primnoides gorgonians, finger sponges, crater and orange golfball sponges. Cam led me upwards to a small cave with an air pocket, allowing us to remove our regulators.

Northern scorpionfish (Scorpaena cardinalis), also called eastern red scorpionfish, quickly became a photo favorite. Larger than their tropical relatives but lacking their venomous punch, they proved abundant and tolerant, allowing a close approach for photography. One hefty specimen beneath an overhang carried some tiny hitchhikers: A duo of blue-dot triplefins perched on its head. I didn’t even see them until I looked at the image on my laptop. Highly inquisitive, red pigfish were another favorite—the males bright red and females paler, with red on top and white bellies. Cam demonstrated his technique to lure them in. Smacking his palm with his fist, the noise enticed one immediately.

Yellow morays curiously poked from crevices, as Sandager’s wrasse, black angelfish, demoiselles and blue maomao sent my camera into overdrive. Contrasting the fray was the occasional pink maomao, totally unrelated to the blue and not even a true maomao. Cam gestured excitedly, and I just managed to glimpse a pair of Lord Howe coralfish, a sub-tropical species found nowhere else in New Zealand. Other rarities include spotted black grouper and mosaic moray. Bronze whaler sharks arrive in winter, but it was still early in the season.

World’s largest sea cave

The islands feature some geological superlatives, and after the second dive, Jeroen wanted to show us one of the most famous. Located in Maroro Bay on the northwest side of Aorangi Island, Rikoriko Cave is the world’s largest sea cave. Encompassing a surface area of roughly a hectare, the interior is 130m long, 80m wide and 35m from waterline to ceiling.

Kevin steered the Acheron right inside, but the scale was impossible to comprehend. It was only when Cam set out in the tender that the enormity sunk in. Pods of orca have been known to enter, and during the Second World War, a Japanese submarine was concealed inside for two weeks while undergoing repairs. The rear of the cave is home to a cup coral species normally found at depths of 200m. Here, it is found at 10-15m, the low light levels deceiving it into thinking it is deeper. Even the remains of a sperm whale lay strewn across the sea bed.

Jeroen wielded a typical Kiwi sense of humor, and I soon became an unsuspecting recipient. After one dive, I noticed a red blemish on my face that was not there earlier. Upon expressing my concern, Jeroen replied it was from too much sun and would eventually go black and sprout long hairs. My alarmed expression resulted in a mischievous grin from Jeroen.

By late afternoon, the day-trippers had gone, and we had the entire place to ourselves. After dinner, Jeroen took us out on a sunset cruise. Setting out, the rugged cliffs glowed russet-orange in the waning daylight. Skirting the cliffs, crabs scuttled among the weeds at the waterline with surf and the occasional seabird the only sounds.

More diving

The Gardens. Still game for more, Cam and I did a night dive at The Gardens. I was surprised there were not more critters about, but the dive itself was superb. The kelp forest was otherworldly, lit by the beams of our torches.

For the pre-breakfast first dive, we returned to Northern Arch. The highlight was a close encounter with a smooth stingray sitting right in the open. I also had my first sighting of a Verco’s tambja, a striking greenish yellow species with blue spots. One of the most common of the Poor Knights nudibranchs, it is usually found on Bugula dentata, a green plant-like bryozoan that is its primary food. Another new species for my list was a pair of longfin boarfish, whose body shape reminded me of freshwater angelfish. Alas, they proved shy. I was shooting with a fish-eye lens and could not get close enough for a shot.

Oculina Point. Our subsequent dives would both be at Oculina Point. With a mild current running, we were able to drift dive along the wall. Inhabitants included speckled morays, firebrick starfish, banded wrasse, leatherjackets. Leopard anemones were especially captivating, their delicate white bodies punctuated with brown spots. While anemones normally spend their existence permanently anchored, these can disengage. If there is not enough space for them to occupy, they will detach and float up or down in currents to inhabit new areas. Further on, an immense wall of magenta jewel anemones made my jaw drop. Later, I had to tone down the colors in the photos. Although accurate, they even looked oversaturated to me.

Critters

Macro life. Yet, the Poor Knights’ magic is not restricted to the grandeur of its seascapes and schools of fish. For the next dive, I swapped wide-angle for macro. Looking closer, I marveled at the intimacy of its microcosms, from jewel anemones to colorful nudibranchs. There was certainly no shortage of the latter. All were species I had never seen before, including sweet ceratosoma (also known as clown nudibranch), mournful aphelodoris, a mating pair of green tambja tenuilineata (fine-lined tambja), Denison’s dendrodoris and even a Verco’s tambja with eggs.

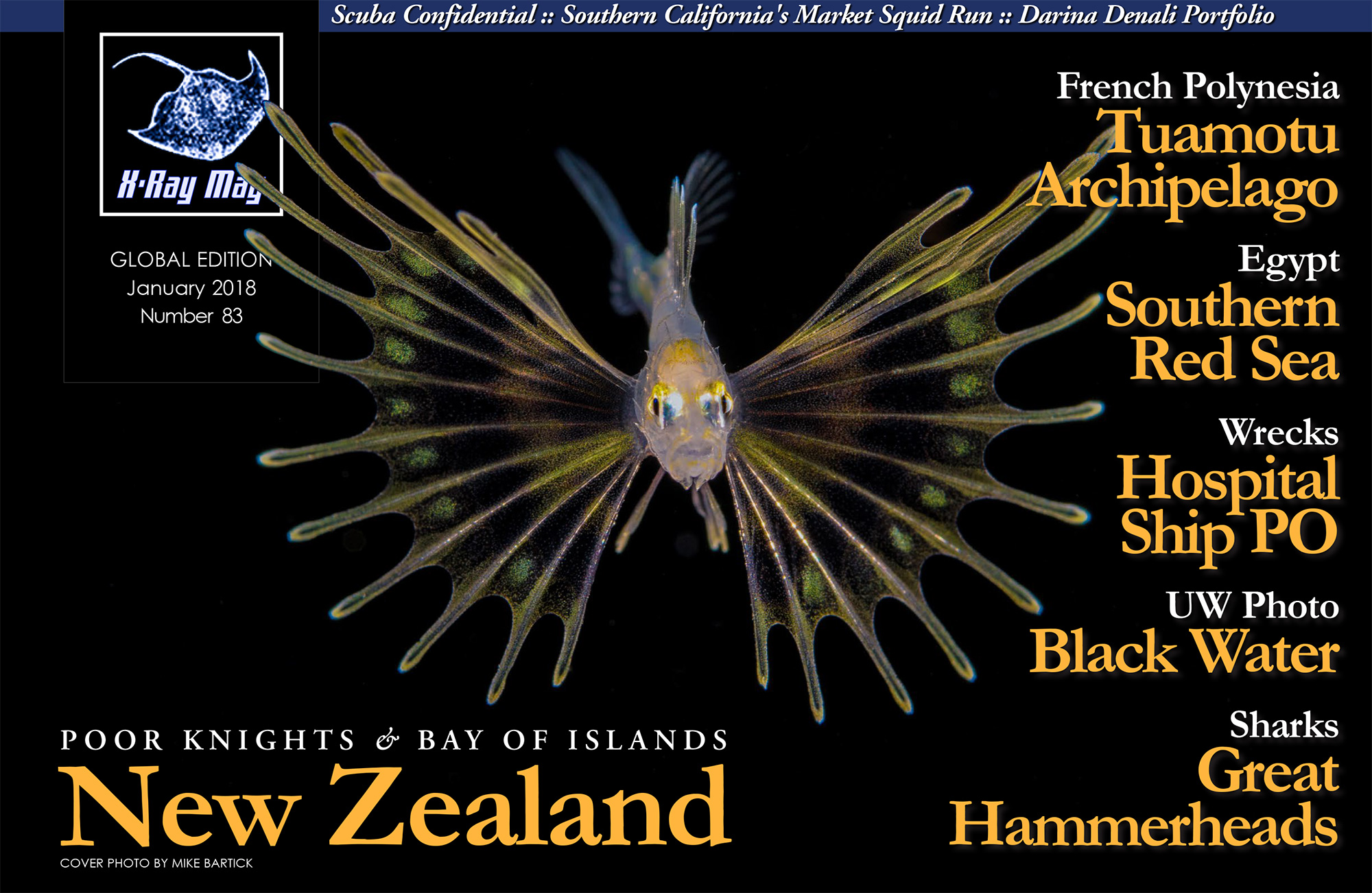

Triplefin. My main quarry was one of New Zealand’s most endearing endemics: the blue-eyed triplefin. One of five triplefin species found in the Poor Knights, they are a photographer’s dream, sporting a red-and white striped body and googly blue eyes. I was baffled as to how I had not yet seen one.

Once I started looking, they were simply EVERYWHERE. Oozing personality, they proved exceedingly cooperative, resulting in frame-filling macro portraits. One rotated its eyes, resulting in one of my favorite shots of the trip. Other notables included crested blennies, yellow-black triplefins and oblique-swimming triplefins, the only one to form schools, swimming close to the reef to feed on plankton. After another wonderful dinner courtesy of Mandy, Jeroen took us out on another sunset cruise. By the time we returned, both Cam and I were simply too knackered for a night dive.

More diving

The next morning had a pre-sunrise wakeup call from Jeroen, as he had something special for us to see. With coffee in hand, I arrived on deck, wondering what was in store. Ahead lay a Maomao Arch, which appeared heart-shaped from our angle of view. “Watch this,” beamed Jeroen. On cue, the rising sun burst through, illuminating the opening with a crimson glow. "A little late for Valentine’s Day, but there you go!” he enthused.

Middle Channel. Heading back south, we stopped to dive Middle Channel, situated amongst the cluster of islands between Tawhiti Rahi and Aorangi Islands. Armed with a macro lens, I happily photographed the exquisite roster of morays, scorpionfish, triplefins and anemones. Topside, the islands continued to dazzle, with Archway Island home to the largest sea arch in the Southern Hemisphere. Kevin steered us right through, where its titanic scale left me gobsmacked.

Blue Maomao Arch. We then continued to Blue Maomao Arch, one of the Poor Knights’ most iconic sites. As the archway faces east, it cannot be dived during heavy easterly swells, but conditions were perfect. Plunging in, we headed straight for the arch with no stops en route. Yet, distractions are commonplace in the Poor Knights, this time in the guise of a smooth stingray resting on the bottom. A few photos later, we continued to the arch but something was amiss. The eponymous residents were restricted to a few scattered individuals. Where had they gone? Continuing farther, we came to a ridge of rock and boulders ablaze with red, orange and magenta encrusting sponges. Photogenic yes, but still no maomao.

Heading back, I turned for a final look and my eyes bulged. Unbeknownst to Cam, an immense school had materialized from nowhere and were practically on top of him. Now, that was more like it! The remainder of the dive was spent photographing the school, with the contrast between the blue fish and colorful wall simply dazzling. Back outside, a Verco’s tambja foraged on bryozoans while a Sandager’s wrasse posed for a portrait. It was only after I later examined the latter that I realized a perfectly camouflaged dwarf scorpionfish was sitting right beneath it.

Jan’s Tunnel. Our final dive was Jan’s Tunnel, a spot we entered on the first evening’s sunset tour. Inside, the cave widened into a kelp-fringed rock pool, only a few meters deep, providing an ideal alcove for sleeping fish. Towards the rear was an impressive congregation of Waratah anemones right at the waterline. Buffeted by the persistent surge, photography proved to be a real challenge. Poking my head above water revealed the natural arch we had seen from the boat.

Exiting the tunnel, we finned alongside the wall for the remainder of the dive. Incredible congregations of jewel anemones shrouded the walls in a variety of colors. As well as the usual magenta specimens, there were also colonies in orange and pink. In a few spots, all three crowded together in a patchwork of sheer audacity rivaling any coral reef. Unreal.

Sadly, it was time to head back to Tutukaka. Even having sampled only a few sites, I could have easily spent a solid week here. Although I missed the mantas, mola molas and mosaic morays, (that’s a lot of M’s), I was hardly disappointed. The Poor Knights is one of the most surprising yet wildly beautiful locations I have ever dived. This, combined with the fantastic experience on the Acheron, had me already contemplating a return visit. After all, how can one argue with Jacques Cousteau?

Bay of Islands

Back in Tutukaka, I bid everyone farewell and set out for the Bay of Islands. After a pleasant 90-minute drive, I arrived in Paihia, the Bay of Islands' prime tourist town. One of Northland’s most beautiful areas, the Bay of Islands encompasses 144 subtropical islands scattered between Cape Brett and the Purerua Peninsula.

Despite the 30-year gap, things looked vaguely familiar. The downtown was busier than I remembered but still maintained a small-town feel. Ahead lay something I did recall, a single-lane wooden bridge to the Waitangi Treaty Grounds, one of the country’s most significant historic sites. It also led to my accommodation at the Copthorne Hotel, occupying a prime location overlooking Te Ti Bay. After dinner at the hotel, I prepared my camera gear for the next day. After the wonders of the Poor Knights, I surmised the diving could not possibly compare. How wrong I was!

I would be diving with Paihia Dive, a shop Jeroen recommended to me before leaving home. Upon arrival, I met owner Craig Johnston, a long-time diver and Bay of Islands native. Craig had spent nine years as senior skipper for Dive Tutukaka, and in 2010, returned to purchase Paihia Dive.

Upon arrival, the shop was a hive of activity, with around 15 divers participating in the day’s excursion. As my gear was getting sorted, Craig introduced me to Faye Stimpson, a divemaster at the shop who would be my dive buddy. Tall, with flowing blonde hair, she proved to be the best model I had ever photographed.

The Rainbow Warrior. Our first dive would be at a vessel known worldwide and one synonymous with New Zealand: The Rainbow Warrior. Greenpeace's flagship, the vessel was en route to the Mururoa Atoll to protest French nuclear testing when it was sunk in Auckland Harbor by French saboteurs on 10 July 1985.

The Kiwis were outraged. In today’s charged climate, the bombing would be regarded as an act of terror and incredulously, conducted by a nation friendly to New Zealand on its own soil. Although France initially denied involvement, two French agents were captured by New Zealand Police and charged with arson, conspiracy to commit arson, willful damage and murder. Membership applications to the organization skyrocketed, especially in New Zealand. Greenpeace soon became a household word and the Warrior eponymous to its cause.

After the bombing, Greenpeace donated the Warrior to the sea and it is now an artificial reef in the Cavallii Islands, situated north of the Bay of Islands. Resting at 22m, it is now a world-renowned dive site and home to a spectrum of marine life. According to Craig, the site is especially popular among visiting French divers.

After a 45-minutes’ drive north, we arrived at the launch site at Matauri Bay. Our transport was an inflatable boat on a trailer hitched to a tractor. With everyone geared up, boat and trailer were backed into water deep enough for the boat could slide off. From the shore, it was only eight minutes to the wreck.

Descending the mooring line towards the sandy bottom, the Warrior’s ghostly silhouette emerged from the blue, an image that was almost eerie. After a few wide shots, we headed for the stern and slowly worked our way towards the bow. Having been underwater for three decades, kelp, bryozoans and sponges were rampant, along with legions of fluorescent jewel anemones.

I concentrated on wide-angle shots, although I suspect closer scrutiny would revealed a wealth of critters. Although we did not enter, the interior contrasted sharply. While rather silty, it was a daytime refuge for crayfish, conger eels, bigeyes and slender roughies. We finished at the bowsprit, the railings festooned with sponges, hydroids and bryozoans along while oblique-swimming triplefins and red moki milled about. This is a dive that absolutely warrants repeat visits.

The Teapot. After our shore lunch, our second dive would be at The Teapot. A relatively shallow dive at 18m, the reef was volcanic in origin and home to huge swathes of kelp. Just like the Poor Knights, the fish were curious and easily approachable. The usual suspects were all here: northern scorpionfish, Sandager’s wrasse, leatherjackets, red moki and yellow morays all seemed to gather for their photo moment. Sponges abounded, as did kina, an indigenous sea urchin I did not see at the Poor Knights Islands.

HMS Canterbury. My final day began with another wreck, albeit a far larger and newer one—the HMS Canterbury—which was situated right in the Bay of Islands. This time, we could take a boat right from the town jetty. After 35 years of service in the Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN), the vessel was taken out of commission in 1995 and sunk on 3 November 2007. Situated in Deep Water Cove (Maunganui Bay), the wreck rests upright on the seabed at around 33-37m, with the upper decks between 22-28m. Penetration is also possible but is only recommended for those with wreck diving qualifications.

Descending the mooring line, visibility was among the clearest I have seen on a wreck. Still, it was impossible to see the entire vessel, and with good reason; at a length of 113m, it was BIG! Despite being underwater for only a decade, the Canterbury was already teeming with life. The bow was especially colorful, bedecked with large clusters of jewel anemones. Due to the ship’s immense size, we opted to stick to the uppermost portions to maximize our bottom time.

Once again, Faye proved a superb model, posing in corridors and looking through windows. Finning towards a porthole on the exterior, she promptly entered an adjacent doorway. Seconds later, her head popped out the porthole. Right on cue, a red pigfish swam into frame to stare at her, creating one of my favorite images of the entire week. I nearly went into deco, and we reluctantly headed up for our safety stop. It was a superb site to which one dive simply could not do justice. Amazing stuff.

Hole in the Rock. After lunch and a shore interval on one of the bay’s picturesque islands, it was time to head for our second dive location. I was thrilled to discover our second dive would be at one of the Bay’s most iconic sites. Situated at the tip of Cape Brett, the Hole in the Rock is one of the area’s biggest attractions and a day-cruise staple. Fashioned by centuries of wind and wave erosion, the 18m arch was named Piercy Island by Captain Cook but is known as Motu Kōkako in the Māori language. Unlike the Poor Knight’s arches, it really was a hole, with its base located well beneath sea level. I hit the jackpot. Not only did we get to see an icon but dive it as well!

Plunging in, the sea floor was strewn with huge boulders, and the constant surge required effort to steer clear of them. Although plant life was virtually nil, the boulders bore astonishing palettes of color. Encrusting sponges of red, orange, purple and yellow adorned every surface while crevices yielded gray and yellow morays and octopuses. Above in the blue, demoiselles swarmed, interspersed with leatherjackets and red moki. Kelpfish, known in New Zealand as hiwihiwi, brandish special pectoral fins enabling them to clasp the reef during strong surge. With so much action, it was difficult to know where to look.

Topside excursion

Craig was kind enough to drop me off right at the hotel jetty, and I had just enough time to change and head to the Treaty Grounds before closing time. It was here in 1840 that the Treaty of Waitangi was signed between the Māori and Europeans, ending a century of conflict and marking the foundation of New Zealand as a nation. On 6 February every year, the site hosts the Waitangi Day Festival to commemorate the event.

The grounds encompass 18.5 hectares, featuring the Museum of Waitangi, Treaty House, Flagstaff and the ceremonial war canoe Ngātokimatawhaorua. Especially impressive was the Meeting House or Te Whare Rūnanga. The interior was especially impressive, an intricately carved masterpiece in red.

Finally, it was time to return to Auckland. In a mere six days, the volume of marine life combined with the incredible scenery, both under and over the water, was enough to leave one grappling for adjectives. Yet, with relatively few operators in the area, diver numbers remain refreshingly scant. If coral reefs are beginning to look just too familiar, New Zealand’s Northland is just what the doctor ordered. I don’t think I will wait another 30 years before my next visit. ■