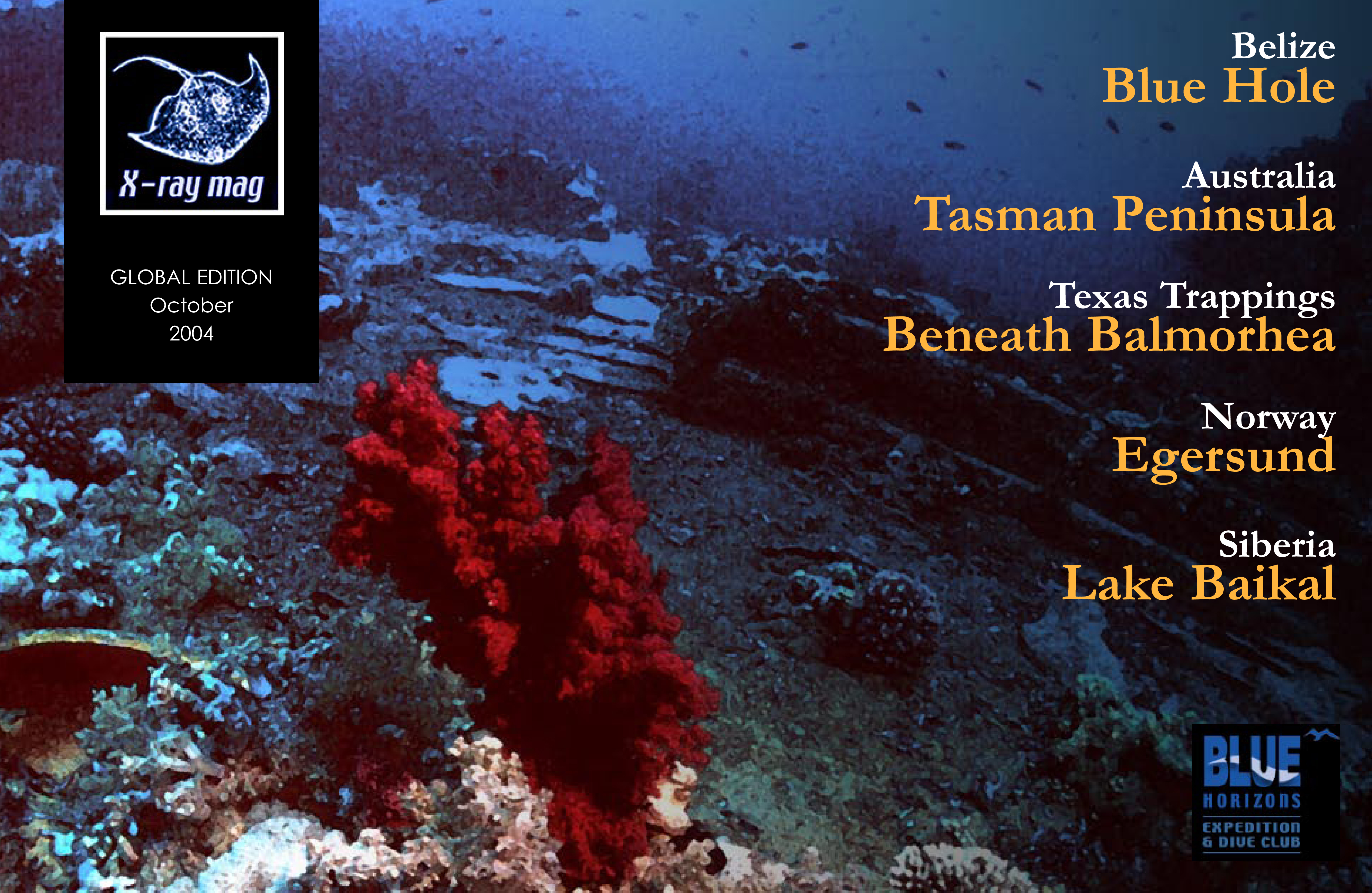

Deep in the heart of Siberia lies one of the world’s largest lakes and one of its seven underwater wonders.

Contributed by

The sudden fall of the Berlin Wall changed the idea of an expedition to Lake Baikal from just wishful thinking to a project that was actually realisable. It would take time, but now here I am at last, and it is with a feeling of the surreal that I now sink down through the cold, clear water.

Beneath me the bottom slowly begins to appear. I can hardly believe my eyes. It is like landing on a strange new planet. It is like nothing that I have ever seen before - not even a slight resemblance is to be seen. The large green sponges growing everywhere are reminiscent of the tall cactuses seen in cowboy movies only smaller.

Between them, the bottom seems to be covered by different soft mosses and lichens. These are also colored a vibrant green with odd patterns.

Strange small fish hide among their branches. I land softly on my knees before a large sponge. Its whole surface is covered by small, psychedelically colored anthropods with far too many legs.

I look around me and observe the landscape with all my senses on full throttle. It could be a stage set from a science fiction film. The fresh water is sparkling clear. The visibility is more than 30 meters, and everywhere I see these green sponges. Above me, I can just make out the outline of our dive boat from which my fellow travellers now also begin to drift downward to land beside me on the bottom of the lake.

The bottom is hard, being rock with loose stones and gravel, and it slopes slightly downwards. Even though it is the middle of July, the water is not more than 4°C, so we all appear and feel like awkward astronauts in our thick dry suits as we move off together down the slope.

We first have to get ourselves a bit organised as we have not tried diving together before.

The expedition consists, in addition to myself, of two Russians and five Dutchmen plus the Russian crew of four. My Dutch colleague, Steven Weinberg, is also a fresh-water biologist, so there is a tendency for us to stop and wonder together over the same strange things to be seen.

Keeping together in that manner, we move off along the bottom when suddenly a vertical drop-off appears beneath us. We stare straight out into black emptiness. It is a little bit spooky. I get the feeling again that I'm in a sci-fi movie with aliens. Da-da-da-dummm – what mysterious creatures are hiding out there in the unknown?

Lake Baikal is the deepest lake on the planet, and you can sense it already close in to the coast.

We glide out into empty space. The whole wall is covered with strange, unknown bizarre creatures that we have never seen before. Sometimes we are underneath an overhang. We pass the 25 meter level on the way down through the ice-cold water. In the distance, we can see the bubbles from Andrey and Gennadij, the Russians who are the other pair in the water.

The wall is exciting. Dramatic. Mystical. But, like in the tropical coral reefs, it is more interesting further up. So, we return to the forest of sponges at 10-15 meters, where we begin to catch glimpses of the many small fishes that press themselves into the cracks and between the stones.

Here, we also find some of the unique anthropods for which Lake Baikal is famous. Like giant amphipods, the fresh-water gammarids resemble something torn out of Jurassic Park. The comparison is not completely inappropriate because most of the species to be found here are endemic – which is to say that they are only to be found here – and have been separated from other lines of evolution for many millions of years.

The lake is possibly up to 50 million years old, and for the greater part of that time has been an isolated eco-system where the evolution of the species has gone its own way. In a way, it can be compared with Australia where the marsupials from kangaroos to the koalas developed in isolation from the rest of the world. It’s just that Baikal’s world lies beneath the surface.

Teatime

The water is really cold, but up on the deck of our good diving boat, we have to get out of our suits quickly in order to avoid overheating. Up here, it is summer, and the air is full of the perfume from the many flowers that burst forth in order to get the most out of the short Siberian summer. The light is wonderful and clear, and the days are long like those of my homeland’s mid summers white nights in Denmark. Sitting on deck clasping a cup of steaming tea, we stare at the mirror-like water and soon fall into our own thoughts.

The tea is strong and comes directly from the samovar, a special Russian tea-making contraption that keeps water hot in a tea pot. It soon becomes a pleasant after-diving ritual to enjoy a couple of ginger biscuits together with the tea. It is very beautiful here and divinely peaceful.

Moscow and all its bureaucracy is already far away. Russia is a fascinating place, but chaotic, and my thoughts glide back to my arrival and all its difficulties. Here, nothing seems to be possible without much discussion and a couple of roubles changing hands. And all the paper shuffling! To check into a hotel can require a multitudinous amount of forms to be fill out.

Thereafter, you can be sent up to the third floor to get the key, show your pass and fill in more papers. If you should desire a bottle of water then you have to go to the fifth floor. Then down to the first floor if you wish to borrow an iron. Elevators are out back and do not stop at floors but on the landings between floors at the turn of the stairs. This means that one has to either walk up half a floor or down half a floor with all one's baggage. Or perhaps more, since not all the elevator's buttons work.

Luckily it was quite different here in Siberia. We were fetched at the airport in Irkutsk by the crew of the boat in a couple of minibuses, and from there on, everything functioned smoothly.

The boat is also well equipped, but there is not much space on board. It is definitely not luxurious. So, if you are used to 5-star live-aboards in the Caribbean, you've got a shock coming. But if you can accept the rather confined conditions and find the right expedition spirit, then the boat is quite excellent for the purpose. There is a big and well equipped stern deck with plenty of space to set out gear and nitrox equipment, plus a big table for cameras, or, as we soon found out, to drink vodka through the long white nights.

Change of temperature

The warmth of the air and the coolness of the water are in continual competition. One moment the warmth of the sun is dominating, and one sits in just a T-shirt gasping in the heat - the next moment one is overwhelmed by an icy cold wind that carries the chill of the water over the railing, forcing one to put on all available sweaters. In the north, there is still snow on the tops of the mountains. It is July, but the ice has only disappeared from the north side of the lake in June.

After the first dives in the south end of the lake, there where the Angara river flows down from Irkutsk, we set a course northwards. On the first part of the coast there are but a few sporadic towns. It is here that the Buryats live. They call the lake a sea and it is holy to them – most people are Buddhists out here.

It is a little strange to look out over the land as there are so many reminders of Scandinavia that it is easy to forget how far I actually am from home, and that we are in the same time-zone as western Australia. Mongolia is just 150 km in a southerly direction from here.

As we move northwards, the coast line becomes more rocky with steep mountain sides and the towns disappear behind us. We see the sun go down and sail on into the night.

The visit to Ol’chon

I woke at the sound of the ship manoeuvring into the ravaged quay built of railway sleepers. There are a number of fishing boats here. Some weird-looking pigment-less fish called golomyanka are caught in Baikal, which are of great economic importance. They are inedible, but half of their weight is oil.

The most important fish for consumption is called omul, and it is sold on the markets just like Danes sell herring; newly smoked, salted, pickled or preserved. It resembles and tastes like a herring but is bigger and slimmer.

We disembark. The island is covered by rocks and a felt-like short grass that bears the marks of grazing. A little less than a kilometer from the landing place lies a village. All the houses are built of dark, tarry wooden beams and the roads are about 50 meters wide. If one could actually call them roads - they are just bare empty spaces of naked earth. I observe three old men smoking pipes in the shadows, men who are trying to fix an ancient tractor, and children playing with their bicycles as we walk through the village to the other end of town.

The landscape is very open. It is a long distance to the horizon and the sky is huge. I recognize that special Nordic light which we have back home in Scandinavia.

Up on the cliff we can see down over "The Shaman Rock," a foot-hill of characteristic shape. The Buryats, the local population, believe in both Buddhism and shamanism, and we see colored ribbons tied around branches and tree trunks. At one place a lot of coins have been placed in front of a little stone alter. There is also a Euro coin placed there, so we western Europeans cannot be completely alone out here.

I am not religious, but there is a remarkable spiritual energy in this place, which influences both mind and body and makes us all a little bit introspective.

Vodka

The Russians are not quite so spiritual with regard to vodka, which we drink far into the white nights. It is difficult to refuse when one is constantly being pressed to take just another one.

Captain Sergei Nikolaijevich had previously flown battle helicopters in Afghanistan - at least that’s what he said. But he appeared to be a man who had no need to boast unnecessarily, nor one you would want to pick a fight with. The military tattoos spoke for themselves, so his story was probably all true.

Despite appearances, Sergei was very kind and friendly. My Dutch diving biologist partner Steven from Luxembourg got into a long conversation with Sergei. The two men were so very different and did not speak the same language.

However, with our Russian diving doctor Andrey as a stumbling translator, they fell into a deep and hearty discussion about the culinary specialities common to Luxembourg and Siberia, and in the end developed a deep brotherhood. Chalk it up to the consequences of quaffing copious amounts of liquid food in relaxed company. By that time, I had discretely slipped away.

Nerpa

Lake Baikal is home to the only fresh-water seal in the world, the nerpa. How it came to be in the lake is something of a mystery since, apart from the fact that the lake is a fresh-water reservoir, the sea is a long way from here - the lake being in the middle of the continent.

One theory explains that very long ago, sea water flowed up the Yenisey river right to the mouth of Angara. Most researchers, however, think that the seals migrated into the area during the early period of the formation of the Baikal depression. It is thought that the seals migrated deeper and deeper into the area in their search for food.

In some years, a total of nearly 100,000 nerpa have been observed in and around the lake. Valued highly for their soft fur and blubber, these animals have been hunted for thousands of years, and archaeologists have found hunting weapons in caves that were inhabited by early seal hunters.

We will also hunt the nerpa today, this time, though, with just cameras and film. The animals are shy. Perhaps they remember our forefathers rather too well, so we must make an appropriate tactical plan.

Reconnaissance first

We sailed round the little group of islands in the ship’s rubber dinghy to scout out the terrain. With eight men in the little boat it seemed a very doubtful enterprise knowing that we lay heavily in the water. There were no life-belts and the lake is icy cold. But we reach one of the islands in safety, landing on a deserted beach from which we move on across the island.

The bottom of the wood is covered in flowers, and the air is fresh. On the other side of the island, we carefully raise our heads above the brink. Below us we could see the nerpa, Baikal’s fresh-water seal and one of the world’s threatened animal species.

Some seals thrust their heads out of the water, others have already made themselves comfortable on large sun-baked stones. The wakes further out on the surface of the lake indicate that there are more seals coming in.

There are some 50-100 seals, and they all look well nourished. We can see different types of behaviour. In one case, for example, the animals lay parallel and appear to be taking turns in scratching each other; and in another case, they are face-to-face in what looks like a boxing match.

The animals normally glide quietly through the water, but if one of us makes a sudden movement, they all become alarmed and flop down tossing and splashing noisily into the water. It is apparently a warning in itself, because the alarm spreads seal panic domino-like along the coast where other seals are enjoying the sun, causing them, too, to throw themselves splashing into the water. Afterwards, one feels a little foolish sitting empty handed, seal-less, watching a couple of hundred expanding rings in the water.

However, with a little luck, one could get to within 10-15m of them, and with powerful telephoto lenses, nearly portrait-like photographs could be obtained. We were so excited and nearly high over this unique and lucky meeting. So, new ambitions began to spring up among the photographers. We will photograph them underwater! A strategy meeting was called, for how could we get within shooting distance of these shy animals?

Commando raid

The solution was an advanced plan in which we would all swim in a long row under the water from one side of the island where the seals could not see us. We would then move in a big semi-circle around the cape in order to arrive in a long row facing the coast where the seals were enjoying the sun on the stones.

Then, one of the local guides placed on the furthest wing, would move close to the coast alone, go up the stones and startle the seals who would then go crashing into the water. Then, we figured the seals would come racing past us while we waited with all our cameras at the ready.

We succeeded, in fact, against all the odds, even after a lot of trouble and care in carrying out that difficult navigational exercise - getting our forces placed as agreed. But the seals were smarter. When we came up, they were lying behind us, further out in the water and looking at us, clearly wondering what these foolish humans were up to. Ah, well! The smart can always cheat the less smart, and this time we were among the latter.

The light nights

The Ushkiani islands are far to the north, so after our unsuccessful attempts to capture the rare nerpa on film, we sailed southwards back through the light nights. We must cross the lake from one side to the other, and the weather begins to worsen. Luckily, I am used to rough seas back home, but several of my colleagues had to go up and "get some fresh air" during the crossing.

At two o’clock, we lay in under the deserted east side of Ol’chon. The island, with its fir-tree covered sides, rises steeply over our heads, and there are no traces of human activity anywhere. In under the coast, there is a plateau in 3-5 meters of water and here the ship, dubbed the Jaques Cousteau ("Sjak Iv Kusto"), is anchored.

A few meters behind the boat, there is a drop-off covered with the characteristic green sponges. The light is fantastic, and the visibility is at least 20 meters making everything appear quite troll-like. In among the sponges, we find the fresh-water amphipods and some small sculpin-like fish. It is the universe of small things, and there are many of them.

The biggest of the amphipods have beautifully drawn legs, with yellow stripes, and under the stones there is a very decorative brightly colored red one.

We made several dives. The visibility and the ambience of the wonderful Nordic light was uplifting. The water is only 4º C, but feels warmer. I have only got 3mm gloves on, but my hands remain warm during the whole dive, which certainly makes it easier to use my camera

We remain there, and in the evening make a camp fire on the beach and eat grilled food. The whole scene is like it has just been taken from a Barcardi advertisement. There is no other light to be seen anywhere. It's just us, a fabulously well equipped diving boat, and an overwhelming natural world, which we apparently have completely to ourselves.

All alone in the world

The next morning, there is a gentle rain, and even though we can see our breath in the air, this morning, too, is beautiful and poetic. The water is as smooth as silk. The horizon is one with the sky in the morning mist, and beneath us, the bottom and the rocks can been seen clearer than ever before. It is so quiet here that our giant strides seem so violently noisy as we splash into our morning dive.

Our cameras are passed down to us and once more we pass over that strange lake bed. Out over the drop-off. Gennadij, the Russian diving guide, has the peculiar daily routine of going down to 100 meters and back. I never did completely understand what he did down there in the cold and darkness, since he didn’t have much time at the bottom, only a lot of decompression afterwards.

Andrey and I take a dive down to about 40 meters. Considering that the water is ice-cold, it is quite sufficient, and there is not much to see anyway down there.

Down at this depth, it is the fascination with the whole scenery that entices me briefly. When I am down there gliding over the coarse rocks with their green covering, and cannot see the surface, it reminds me somewhat of a trek in the mountains in foggy weather. And beneath everything, I hear that internal repetitive mantra. "I am a long way from home... I am exploring a whole new world... I am a long way from home... I am exploring..."

We really are just by ourselves out here beyond the edge of our familiar world. When we sail, we see no other boats, and at night there are no other lights to be seen.

Behaviour

It is the gammarids that interest me most on these dives. These enormous monstrous crustaceans are called "water fleas" back home, a popular Danish term, or layman's expression, for the small amphipods one sees “everywhere” in kelp at the beaches. Here, they are everywhere evident in the landscape and seem to dominate the eco-system.

I have photographed at least 8-10 different species. It is going to be very interesting to identify them all. At the moment, I really have no any idea about how I will do it - that challenge must come later.

I lay on my stomach in front of a large cactus-like coral and observe a pair of large acantogammarus feeling each other with their antennae. Is it for dominance, communication or foreplay? Both of these armour-plated monsters seem to be very focused on their activity and ignore me when I get as close to them as the focus of the camera allows. I nearly grill them with the light of the flash.

There are several of these animals collected together on this coral. It seems like a meeting place. I can but wonder what this behaviour means.

Further down the slope I find an anchor completely covered with soft green coral - the perfect wide-angle shot. It's a pity that I just have the macro-lens with me this time instead of my wide-angle, and it's our last dive here. But that’s how it is when you are on a live-aboard, one must keep moving onward.

Solid food

We often eat on deck, and what surprises me during these meals is that there are no mosquitoes. I had expected Siberia to be one complete plague of mosquitoes, but the only insect bites that I received during the whole trip were from a couple of mosquitoes in Moscow, and an ant bite when I crawled around on the Uskiani islands in order to come within shooting distance of the nerpa seals.

The food is solid Russian or Siberian peasant cooking. The cuisine has a total lack of finesse, but holds its own charm regardless. For better or worse, it is not adjusted to suit the tastes of the guests. So, if you are prepared to eat what the local people eat, and accept it as a natural part of the adventure, then you can get a whole new experience. If not, then you have a long way to go to get to a MacDonald's.

Both the heavy midday meal and the somewhat lighter evening meal start with a thick soup and bread. There is often some sort of local fish in the soup. After which, comes the main dish consisting of meat, gravy and potatoes with which one drinks vodka. To round off the meal, there are biscuits, sweets and tea from the samovar.

Breakfast is just as solid and heavy as dinner. As a rule, we get some form of light, rather delicate porridge to start with, followed by bread, cheese and sliced meats. The porridge is one of the things that I remember with the greatest pleasure. It was really quite good on the palette and in the stomach.

The life of the lake

Strangely enough, in spite of the fact that Lake Baikal has long been accepted by biologists as being unique, there are nearly no existing book guides to life in the lake - not even in Russian. This is true even despite the fact that there has been an internationally known fresh-water biological institute on the shores of the lake since the 19th century to which researchers from the whole world have travelled since the time of the tsars.

Of the few works there are to be found, most are old and practically unobtainable, (e.g. ”Fresh Water Sponges of the USSR” from 1936 and ”Amphipods of Lake Baikal” from 1945).

A Russian scientist, D.N. Taliev, wrote already in 1948, that “… Baikal is a unique natural laboratory without comparison in the world, where one can study the formation of new species and evolution. A laboratory which can contribute to insight into, and understanding of how these processes take place in plants and animals, and so can lead us to a deeper understanding of how life on the entire Eurasian continent developed as a whole.”

Oleg Anatolyevich from the Fresh-Water Laboratory in Irkutsk adds, “Regarding the richness and variety of its species Baikal takes an absolute top place among the lakes of the world. The number of known species and variants is currently 2491, which is more than twice as many in its closest rival, Lake Tanganyika in Africa.

But even that figure is only a beginning, because in our own fresh-water biological institute, 20 new animal species are described annually. My forecast is that Baikal will be found to contain more than 4000 species of animals and more than 2000 plant species. For a long time in the future, Baikal will be a powerful centre regarding research both in general biology and in evolution, and in fresh-water biology where publication of guides has a very high priority.”

Afterthoughts

Baikal is such an intense and strange experience that it is a challenge to one’s vocabulary to find the right words to describe what one feels on the journey. When we returned from our round trip that had taken us 500 km up and down Lake Baikal, and were on our way up the Angara river towards Irkutsk, I felt enriched and grateful. Both the travel itself and the knowledge of having fulfilled a wild dream from my youth gave me a wonderful feeling of satisfaction, which I now sat and enjoyed quietly as the banks of the lake glided slowly past me.

Looking back, what surprises me most is how easy it was to get there, and how well organised the diving was in Siberia. In reality, the greatest barriers to reaching this ancient lake were my preconceptions of a remote impassable wilderness, a broken-down infrastructure and an insurmountable bureaucracy. But from the moment we landed in Irkutsk, we were well looked after.

I don’t know if I will return to Lake Baikal. If I do, it will probably not be very soon. One should never try to repeat uplifting experiences; you risk spoiling meaningful memories. But I do hope that others will follow in our footsteps, and that divers all over the world will come to know about this unique place. There is room out there for every adventurous naturalist, and the resulting eco-tourism would be the best environmental protection that the area could get.

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #1

- Read more about X-Ray Mag #1

- Log in to post comments