Elliptical in shape, Reunion Island is located in the southern Indian Ocean, 800km east of Madagascar as the crow flies, and 200km west-south-west of Mauritius Island. With a surface of 2,512 sq km and a perimeter of 207km, it is the emerged tip of a volcanic mound that rose 7,000m above the ocean floor. Pierre Constant shares his adventure to this exotic and remote island.

Contributed by

When the supercontinent of Gondwana broke up 160 million years ago, the opening of the Indian Ocean coincided with the split of India from the African mainland. India drifted in a north-easterly direction. Sixty-five million years ago, the Indian Plate was located precisely where Reunion Island lies today (21°S, 55°30’E). It was the birth of a “hot spot,” which led to exceptional volcanic activity.

Magma floods spilled out like the icing of a cake and created the titanic, 1.5 million sq km plateau of the Deccan Traps, west of India. It is contemporary to the impact of the Chicxulub meteorite in Yucatán (66 million years ago) and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary, which led to a massive extinction and the disappearance of the dinosaurs. As the Indian Plate moved farther northward, leaving behind the continental block of the Seychelles, the hot spot gave birth to the Maldives, the Laccadive Islands and the Chagos Archipelago.

A rift appeared between the African (Somalian) Plate and the Indian Plate 45 million years ago, and the hot spot moved under the former. Rather dormant for the next 30 million years, it became active again 10 million years ago, consequently creating the Mascarene Islands, which comprises Rodrigues, Mauritius and Reunion Island. Among the three, Reunion is the youngest and would have erupted only three million years ago. It is composed of black basaltic lava. Piton des Neiges (3,071m) is the original volcano, followed by Piton de la Fournaise (450,000 years ago).

History

Although the Arabs were to place the island on the marine chart in the middle of the 12th century, under the name Dina Moghrabin (Island of the Occident), Portuguese navigator Pedro de Mascarenhas disembarked in 1513, giving his name to the Mascarene Islands. The island’s history is closely related to that of nearby Madagascar. After a failed fateful attempt to establish themselves in Madagascar’s southern location of Fort Dauphin in the 17th century—due to aggressive local tribes and the devastating effect of malaria fever—Jacques de Pronis of France moved the colony in 1642, to a then deserted island farther east.

Taking possession under the banner of the French king Louis XIII, the French landed in St. Paul, and named the island Ile Bourbon.

Some 20 years later, Malagasy slaves were brought to the island. With the creation in 1664 of the French East India Company, Jean Baptiste Colbert sent four ships to the island.

In 1715, Bourbon’s governor started cultivating coffee beans. Many African and Malagasy slaves were shipped to work on the farms. Some of them fled to the pristine forested highlands of the interior to escape their masters and came to be called the “marrons.” Following the French Revolution and the abolition of royalty, the island was renamed “Reunion,” in reference to the reunion of the Parisian and Marseillais revolutionaries.

Despite a mutiny of the slaves in St. Leu in 1811, slavery was not abolished until 1848. Sugar cane was introduced to replace the ailing economy of coffee, and an Indian workforce was brought to the island by the planters. Indo-Muslim and Chinese immigration followed in the early 20th century. In 1946, Reunion Island became an overseas French department.

Dive operations

There are about 50 dive centres on Reunion Island, with most of them located on the western coast. The busiest dive areas are St. Paul and St. Pierre. I met dive operator Laurent 12 years earlier on Madagascar’s Nosy Be Island, where he once operated Oceane’s Dream dive centre in Ambatoloaka. Since then, he has relocated to Le Port, slightly north of St. Paul, where the first settlers arrived in the 17th century.

The renowned Cimetière Marin (Marine Cemetery) in St. Paul is the resting place of many early colonialists and slaves, including the infamous French pirate Olivier Levasseur (born in Calais on 5 November 1695). Known as “La Buse,” he terrorised the Indian Ocean after skimming the Caribbean Sea. Associated with the British pirate John Taylor, Levasseur was credited with the capture of the Portuguese navy ship Nossa Senhora do Cabo (St. Denis, April 1721). He was hanged in St. Paul in 1730, at the age of 45, for acts of piracy.

Fish life

Being primarily volcanic, diving Reunion is not to be compared with the rich coral reefs of the tropics or Indonesia. The fish and marine life are a mix of the Indo-Pacific fauna and that of the Indian Ocean. Fortunately, some fish species are endemic to the Mascarene region, and I would be clearly in search of those.

Since humans settled on Reunion Island almost 380 years ago, the island has been heavily fished, affecting fish populations and anything big, including sharks. The number of fishing lines found underwater is testimony to this. What remains are reef fishes, though colourful. Small fish schools are limited to common species such as Bengal snappers (Lutjanus bengalensis), yellowband goatfish (Mulloidichthys vanicolensis), goldspot emperorfish (Gnathodentex aureolineatus), sleek unicornfish, damselfish, butterflyfish, triggerfish and surgeonfish.

I did not see any sharks on any dives. Laurent confirmed that they were almost gone from the seascape. Nonetheless, for the past ten years, shark attacks (mostly bull and tiger sharks) at beaches have given Reunion Island a bad reputation. “But it only happened to bathers and surfers, not divers. I just do not see sharks underwater,” said Laurent.

Whenever an accident or a fatality occurs, the local government is quick to react with a massive cull and shark hunt, killing whatever they can find. Major beaches on the western coast are protected by shark nets, and the unfortunate creatures have virtually no right to live.

Diving

Most of the diving community was local, mainly French expats, as foreigners were practically unheard of. Based in Le Port, Dodo Palmé dive centre, founded 20 years ago, was run by Manu and his partner Laurent. Together, they were a cool, happy-go-lucky team, which currently offered a lot of training and courses of the French FFESSM school, conducted by the charming Malagasy-born Morgane (daughter of Laurent) and a number of local instructors who pop in whenever needed. They were all friendly, good-natured people.

Diving was done on a daily basis: one dive in the morning and one dive in the afternoon, depending on the wind, swell and sea conditions—except on Mondays when the dive centre was closed. After each dive, “ti punch” (rum and orange juice) was served at the bar; it was a tradition! Weekends were the busiest time. Dodo Palmé used an 8.5m aluminium boat, with a capacity of four to 12 divers. Night dives were conducted exclusively on Fridays before sundown.

The underwater landscape around Reunion Island was typically that of basaltic lava flows, carved by a maze of canyons, caves, swim-throughs, small arches, with lots of brown, salt-and-pepper-speckled expanses of volcanic sand.

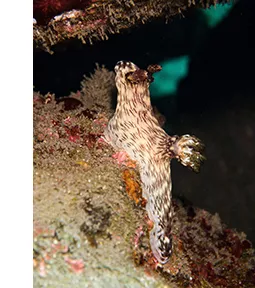

Cape La Houssaye. About 20 minutes from Le Port, southbound towards Boucan Canot, the cape was a basaltic extension of the land with a cliff carved with holes and caves. A school of two-tone chromis (Chromis fieldi), which are half black and half white, was seen among schools of yellowfin goatfish and convict tang (Acanthurus triostegus), which were creamy white with thin black bars. A cute orange frogfish (Antennarius commersonii) inhabited the seafloor, often camouflaged on a sponge of the same colour. An evasive school of squid in stealth formation, flying over the sand, were curious of divers, but not tame! Worth having a look, the cave was actually an 80m long tunnel, with a cloud of golden cave sweepers (Pempheris vanicolensis) around the entrance. An old cannon was an oddity resting on the basalt reef. The cape was a good spot for critters and nudibranchs such as Glossodoris hikuerensis, Bornella anguilla and Hypselodoris pulchella.

La Barge, nearby, was the wreck of an elongated floating platform at a depth of 24m, with a resident school of Bengal snappers. Lionfish (Pterois volitans) hid inside the broken hull. Some old rusty anchors were found on the sand some distance away.

Le Houlographe was a floating buoy designed to measure the swell. It was a deep dive along the anchor chain, down to 34m and beyond, where one could see a forest of white gorgonians. I noticed an interesting deep-water species, the African butterflyfish (Chaetodon dolosus), with a black mask over the eye and a black band along the caudal end. Some bearded scorpionfish (Scorpaenopsis barbata) gazed at me with a serious expression. I also marvelled at the Mauritian anemonefish (Amphiprion chrysogaster), which was all black with three white bands, an orange belly and a white band on the caudal fin. The species is endemic to the Mascarene region.

Maharani. The afternoon dive took place at the tiny beachfront and rocky shore of Boucan Canot. There were big patches of lava in-between vast expanses of volcanic sand. Swim-throughs and small canyons added some spice to the dive. My eyes were caught by an attractive black-banded hogfish (Bodianus macrourus), endemic to the Macarene Islands. Peacock groupers (Cephalopholis argus), sea chubs and large yellowtail snappers roamed the area. Orangespine unicornfish (Naso lituratus) were a visual treat.

Le Vieux Fusil. Offshore from Le Port, this was another deep-water dive, in the 39m zone, where a ledge was found on the bottom. A cloud of black pyramid butterflyfish (Hemitaurichthys zoster), with a white band between two dark bands, was the attraction here, along with Indian doublebar goatfish (Parupeneus trifasciatus)—which had a crimson red and white body with dark bands and thick lips—as well as clouds of red soldierfish. A yellowmouth moray (Gymnothorax nudivomer), which was brown with white dots, stared at me shyly from a hole in the rock. After 25 minutes on the bottom, a 11-minute decompression stop was compulsory.

Les Douanes was located near the eastern side of Le Port. Nothing to rave about here. The bottom was a collection of rounded boulders at 18m, with a lot of brown sand all around. However, the presence of a species of stonefish (Synanceia verrucosa), which was grey and pink, was worth a mention. Unusual and lovely was the shadow butterflyfish, or brownburnie (Chaetodon blackburnii), with a black body, yellow tail and white face; it is endemic to the triangle of East Africa, Madagascar and Mauritius.

Also noted was the Madagascar butterflyfish (Chaetodon madagascariensis), which had a black chevron pattern on a white body, with half of the rear in orange. A geometric moray (Gymnothorax griseus), which was greyish white with tiny black dots on the head, poked its head out with curiosity from under a boulder. Stuck like an equilibrist between two rocks, a white leaffish was not photographer friendly. Les Douanes was also an interesting night dive where beautiful red or orange Spanish dancers (Hexabranchus sanguineus) could be observed. A rather similar deep dive was found at L’Ecole, a stone’s throw away.

On to St. Pierre

In order to try another location, I drove down to St. Pierre, some 45 minutes south of St. Paul. The unpretentious dive centre of Kazabul, run by Julien (a local character straight out of a Western movie), was found at the harbour’s marina. He took people out on his 5.5m semi-rigid inflatable boat powered by a Suzuki four-stroke outboard motor, in which he could happily fit ten divers, like sardines in a can. The diving here was different.

Jardin de Corail. The dive site of Jardin de Corail (coral garden) in the bay of Grambois had a reef flat at a depth of 12m, literally covered in hard corals. As we swam farther offshore, there was a reef wall between 20m and 30m of depth—an impressive sight, punctuated by Dendronephthya sp. soft coral, purplish pink in colour.

As one overlooked the sandy bottom below, the drop-off was carved by gullies. Fish life was inconspicuous though. Encounters included humpback unicornfish (Naso brachycentron) and elegant unicornfish (Naso elegans), as well as surgeonfish species such as the eyestripe surgeonfish (Acanthurus dussumieri) or the Indian sailfin tang (Zebrasoma desjardinii). Mixed schools of Bengal snappers and goldspot emperorfish (Gnathodentex aureolineatus) mingled along the wall.

Back to Le Port

I then resumed my experience with Dodo Palmé for some more dives.

Pain de Sucre. A thumb-shaped rock near Cap La Houssaye, this was a rather shallow dive at 15m but attractive enough with a maze of passages among rocky patches, including narrow canyons, overhangs and caves. There were hunting pairs of blacktail snappers (Lutjanus fulvus) and bluefin jacks (Caranx melampygus) as well as a couple of hawksbill sea turtles, one of which was bearing a GPS tracker on the top of its shell.

There were many species of surgeonfish such as eyestripe surgeonfish (Acanthurus dussumieri); doubleband surgeonfish (Acanthurus tennentii); epaulette surgeonfish (Acanthurus nigricauda), which were dark brown with a white band on the base of the tail; and spotted or two-tone tang (Zebrasoma scopas), which was a greenish brown and had a pointed nose. Morgane enthusiastically pointed out several longlegged spiny lobsters (Panulirus longipes) hiding in the cracks of the labyrinth. Bigeyes (Priacanthus hamrur), crimson red in colour, loomed everywhere in the darkness.

Photo: Pierre Constant

Tahiti dive site faced the big fuel tanks of eastern Le Port. A rocky shelf at 5m was covered with broccoli-like hard coral, white in colour. Under the overhang, curtains of Bengal snappers and red soldierfish abounded. Giant cobblestones bedecked the slope below, which plummeted down to 40 metres on sand. Big rock patches were found at depth, some with gorgonians and schools of blacktail snappers circling in oblivion. A tame hawksbill sea turtle grazed between the rocks. Morgane showed me an exquisite zebra moray eel (Gymnomuraena zebra), which was reddish brown with thin white stripes, sharing its hole with a little green moray eel. In the shallows, little clouds of sea goldies (Pseudanthias squamipinnis) were an enchanting dash of orange (females) and pink (males), adding merrily to a rather austere landscape.

Myriam, Laurent’s wife, was a keen underwater photographer with a sharp eye for small stuff and critters. She would gladly point out a species that one would not even notice. A professional guide and lecturer as well, she led people on historic tours in French, English and Russian.

La Tour. We had our last dive together with Laurent at La Tour, near Boucan Canot. The site was gifted with fabulous visibility and excellent sunlight. It was a wide-open space on the edge of a rocky shelf, with canyons and swim-throughs, as well as islands of boulders in the sand. There were many species of groupers, including the masked grouper (Gracila albomarginata), white-edged lyretail grouper (Variola albimarginata) and the conspicuous blue-and-yellowfin grouper (Epinephelus flavocaeruleus), which turns rather dark and dull as an adult. We encountered a yellow-edged moray eel (Gymnothorax flavimarginatus) under a little rocky patch in the middle of a salt-and-pepper sandy flat. It was a cosmic experience on a perfect day.

Volcanoes

No visit to Reunion Island would be complete without a visit to the three volcanic “cirques” (amphitheatre-shaped valleys) of Cilaos, Mafate and Salazie. These are found within a heavily eroded volcanic caldera, which belongs to the Piton des Neiges volcano in the central-western area of the island. To enjoy this properly, you need to hire a car for a better approach. Then it is all about hiking and trekking to climb the mountains or to experience the wet forest with beautiful Cryptomeria trees, an endemic conifer of Reunion Island, as well as giant acacia trees bearing mosses and lichens, wrapped in fog.

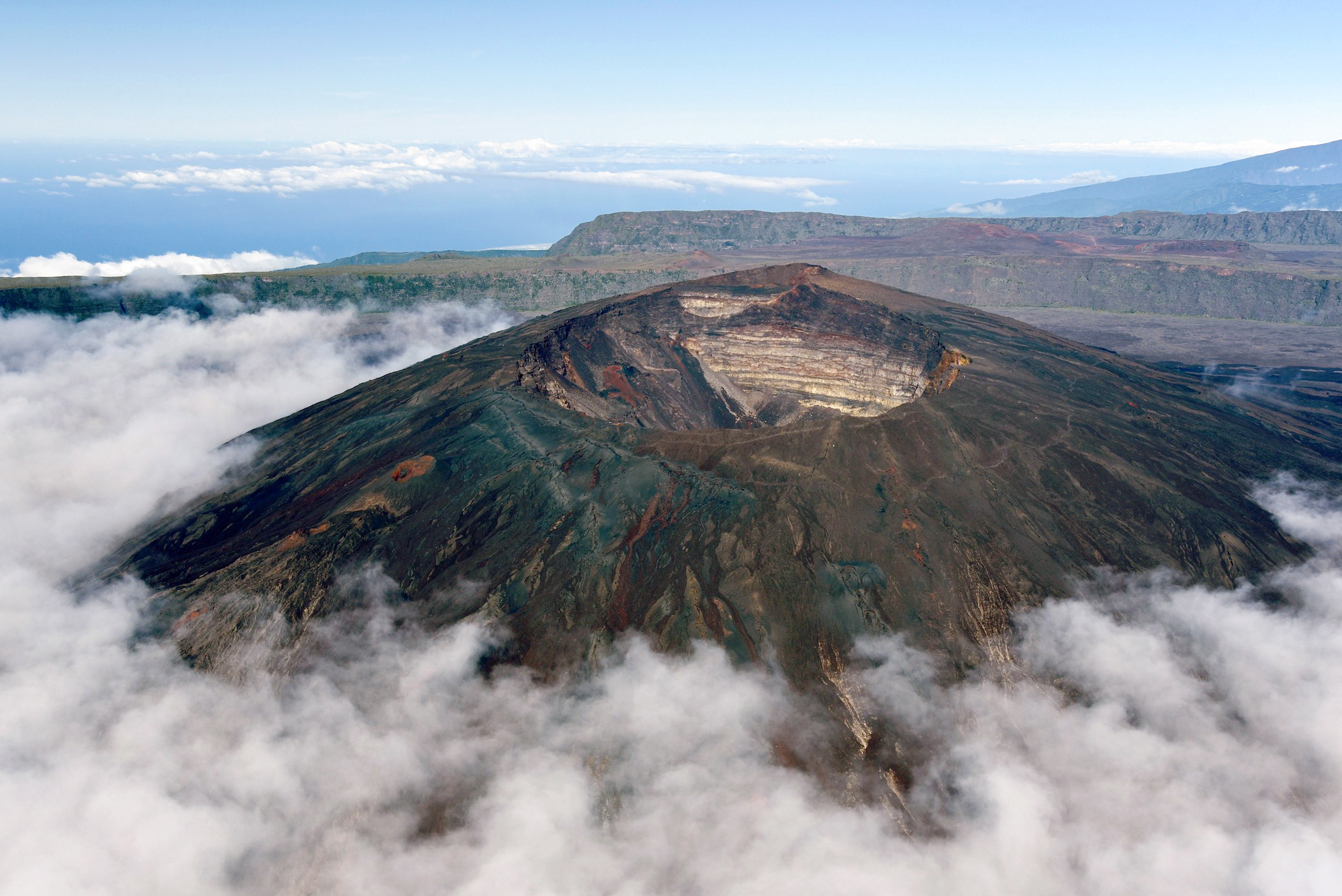

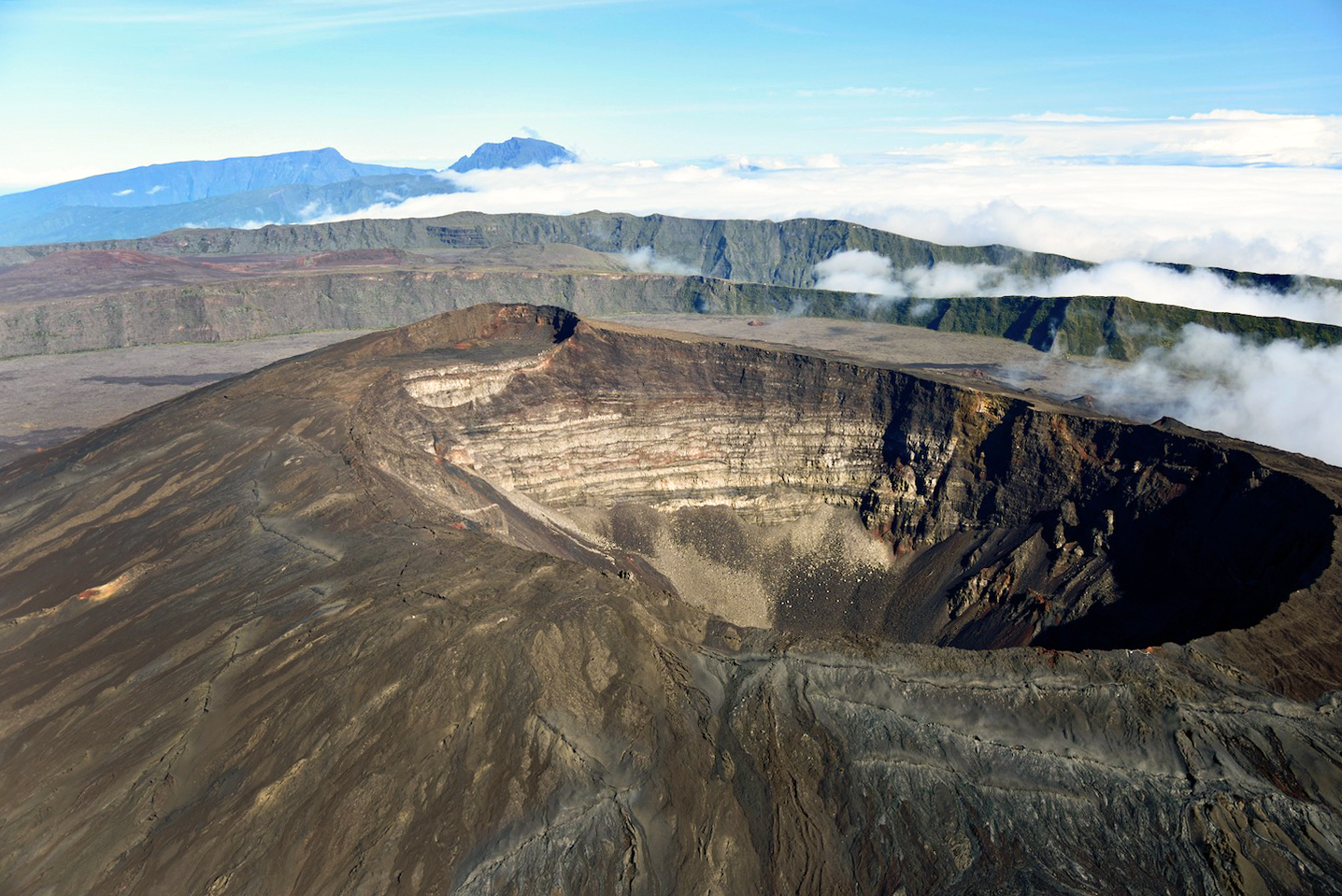

A must-do on your wish list is the unforgettable Piton de la Fournaise, better known as “The Volcano”—and a very active one at that! From Le Tampon and the desert heights of Plaine des Sables—amidst a unique lunar landscape—one reaches the end of the potholed dirt road at Pas de Bellecombe. From there, you enter the gate with a red-and-white signboard, which warns you that an eruption could possibly start in the next few days, and then you climb down into the caldera.

On the pahoehoe lava flows (ropy lava), one passes by the charming red-and-black tuff cone of Formica Leo, on the way to the imposing central volcano rising in the distance. Following the initial approach, the four-hour return hike leads one up to Cratère Dolomieu (2,632m), a 350m deep explosive pit, which is all that is left after Piton de la Fournaise blew its top in 2007. Numerous eruptions have taken place since then, with the last one occurring in 2019.

Ancient lava flows on the southeastern coast attest to the various events that cut the circular road repetitively. You will get a pretty good idea about how vegetation such as mosses, lichens, ferns, shrubs and trees colonised the new land over the years. Incredibly, the church of Notre Dame des Laves near Sainte-Rose was encircled by lava flow in 1977 but was somehow left standing and undestroyed in its pink and white aura. Locals were prompted to call the event a miracle of divine intervention.

Waterfalls on the forested slope and in the depths of the ravines are a big attraction of the island on a hot day. Some of them may be too hard to reach, but Anse des Cascades near Sainte-Rose and Cascade Langevin on the southern coast, are definitely worth a look, for a dip or a picnic in a very natural environment.

Air time

On a couple of dives with Dodo Palmé, I met a guy named Hans, who was a CSI policeman by night and free bird by day. This native Reunionese confessed that, deep down, he was a core enthusiast of flying. We had a nice chat, and once he understood the nature and purpose of my visit to Reunion Island, he surprised me with an invitation: “What about a flight in a ULM (ultralight aircraft) over the island? Say, next Wednesday? I have a window…” An offer I could not refuse.

However, when the day came, the weather was not in our favour. It had been raining, and the fog would rise over the mountains. The flight was cancelled at the last minute. I was so disappointed.

“Postponed until next week?...” Hans suggested. So, I met him one early morning at the Planetair 974 shed at Pierrefonds Airport (near St. Pierre). This time, the gods were auspicious, and the weather was awesome.

Photo courtesy of Pierre Constant

Sporting a flashy cherry red, the little twin-seater aircraft rose above Rivière des Remparts towards “The Volcano,” which emerged from a ring of clouds. We circled the impressive Dolomieu Crater, and then headed towards the dented rim of ancient Piton des Neiges, crossed Cirque de Cilaos towards Col du Taïbit (which I had climbed a week earlier in the forest), and headed to the Cirque de Mafate and its charming little villages spread out on diminutive plateaus in the green nature, and then went on to the balcony (a panoramic viewpoint) of Maido, where I had been caught walking in fog, rain and wind. Finally, the ULM glided down towards St. Gilles on the western coast, over the pastel-green reef flats of Passe de l’Hermitage, the elongated lagoon of La Saline, and the town of St. Leu. It was exhilarating!

Without a shadow of doubt, after diving the depth of Reunion, an eagle’s view of the island provided memories that would last forever. I made new friends here at Dodo Palmé, and who knows, I might be tempted to come back one day to explore more of this breathtaking hot spot, a jewel of the southern Indian Ocean. ■

With a background in biology and geology, French author, cave diver, naturalist guide and tour operator Pierre Constant is a widely published photojournalist and underwater photographer. For more information, please visit: calaolifestyle.com.