This is a story about a “cave man” in paradise. OK, you smile, that is a good start, as this tale will certainly whet your appetite. Pierre Constant shares his adventure diving the caves of the Mikea Forest in South Madagascar.

Contributed by

My compulsive relationship to Madagascar has been a steady affair of the heart for the past 30 years. In 2012, curiosity brought me to explore the sinkholes of the Great South. I devoted my time to investigating various sites on the Mahafaly Plateau to the south of Tulear. From my experience of cave diving in South Australia, I understood that caves and sinkholes, connected to underground rivers, were a source of unexpected finds—such as fossils of extinct prehistoric animals. I assumed Madagascar would certainly yield such a bounty of hidden treasures, as was the case in Brazil or Mexico.

Following the break-up of Gondwana, Madagascar separated from Africa 130 million years ago in the Jurassic period. A vast sedimentary basin had been formed between the island and the African mainland. This explained the presence of significant limestone deposits on the western coast of Madagascar, from the “tsingy” (karst badlands) of Ankarana in the north to the tsingy of Bemaraha near Morondava and all the way to the south of the Great Island.

Like a gold digger who found a lucky streak, I kept coming back. The lure of the Great South and its enchanting spiny forest, together with the discovery of sinkholes—locally known as “aven” or “dolines”—had me hooked over the years.

Back in 2011, I explored the region of Itampolo. In 2012, the sinkholes of Tsimanampetsotse National Park fascinated me. There, I had discovered skulls and the skeleton of an extinct dwarf horned crocodile (Voay robustus). This reptile had appeared in the Holocene (11,700 years ago) on the southwestern coast of Madagascar.

Finding fossils and remains

Diving Binabe Cave, located north of Onilahy River near Sarudrano, I found the femur of a dwarf hippopotamus (Hippopotamus lemerlei) in the sediment, at a depth of 25m. Scientists of the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) at the Museum of Natural History in Paris dated the bone with carbon-14 and proclaimed it to be 1,400 years old.

A few months later, in a remote sinkhole of the Mahafaly Plateau, I fell upon the lower jaw of a dwarf hippo—a species that became extinct due to human predation (hunting) as early as the 7th century. Discovering it was incredibly exciting, of course. Soon after, the fossil site of Tsimanampetsotse was closed by the Malagasy authorities following abuse and piracy by some unscrupulous people in search of loot and profit. A very saddening fact, indeed.

In September 2015, I ventured into new territory: the Belomotra Plateau, north of Tulear. A karstic environment in the Eocene limestone (56MA to 34MA), hidden in the Mikea Forest. The area supports species like arid, spiny bushes of Euphorbia sp., Alluaudia sp., and Didiereaceae sp. (octopus trees), as well as giant Pachypodium succulent plants and enormous baobabs, such as Andansonia za, Adansonia rubrostipa (bottle baobab) and Adansonia grandidieri—amazing endemic plants from southern Madagascar.

Only accessible with a sturdy 4x4 (four-wheel-drive vehicle)—because the trails were rough and very sandy—this God-forsaken region was home to an indigenous tribe surviving in the wild: the Mikea people. They knew about the existence of caves and waterholes, where they had gone from time immemorial in search of water and bats, upon which they fed. Without their help, I would have been unable to proceed with my explorations.

For some time, businessmen from Tulear prospected there, looking for bat guano in dry caves. This was exploited for a number of years that saw a local work force loading trucks with big bags of guano. I had checked some of these caves, only to find little water or no water at all—a bitter frustration, considering the distances it took to get there and the tough walks under a scorching sun.

“Ali Baba” cave

In 2015, fate turned positive, when I heard about a magnificent cave, which I instinctively named “Ali Baba” cave. It was a fair walk into the Mikea Forest, on a reddish sandy trail, carrying dive equipment. Hardly noticeable at all was a lentil-shaped opening in the bedrock, which was a portal into the underground. One had to duck under an uncomfortable and narrow passage with a low ceiling. A slippery slope in the pitch darkness, with loose rocks, opened into a fascinating chamber with stalactites, stalagmites and “dantesque” pillars.

There, 15m to 20m below ground, I marvelled at a subterranean lake with more pillars—a cryptic cathedral. The air was stale, hot and humid—so aggressive that one would sweat profusely. Breathing was even difficult. Bats fluttered about in the darkness. Cockroaches crept everywhere on the damp guano floor. It felt like a sauna.

Diving

Double-checking my dive equipment carefully, I handed my head lamp to the Mikea guide. “Just turn on the light upon my return,” I said, slipping into the water. For the first 5m to 7m of depth, endemic white blind fish (Typhleotris pauliani) survived on bat guano. The clear water had a balmy 28°C temperature.

At the far end of the lake, the bottom dropped steeply into twisting passages, among stalactites and pillars in golden and brownish colours, against a pastel-green background. The farther I sank, the whiter the limestone became, with outstanding decorations. At a depth of 20m, a restriction forced me to squeeze through, trying not to get stuck, which indeed happened at least once! Then there was another gate, after which the cave opened up in magnificence, into a snaky tunnel.

The farther I pushed forward, the more I was struck by the beauty of the cave. It was pure fantasy come true. Yet, as a solo diver on a single tank, I had to be realistic about my limitations. Without the shadow of a doubt, I knew it was not the end of it.

Diving “Ali Baba” cave on a couple of occasions in 2016, my exploration went farther into a succession of chambers. In one of those stood what looked like a replica of a stinkhorn mushroom (Phallus impudicus) before a cascade of stalactites. It was such an awesome sight that a morbid thought crossed my mind: Should I have to die one day, I would not mind being in a tomb like this. It was a cryptic paradise, truly hypnotic, far away from the outside world.

Rituals

Fresh revelations from my local host gave me hints about caves in the area, with a new direction for my research. A courtesy visit to the “fokontany” (a.k.a. the local chief) was compulsory. Somehow, my interests were triggering someone’s nose for profit. Some people may want to get “a piece of the pie,” so to speak. So, the quieter I could be about my intentions, the better. “But you must pass by Mr. Faazoua for the ‘fomba’ ritual!” warned my host, Diana, deadly serious. “We do not wish any problems with the community.”

A prayer to the cave spirits was to be performed by an obscure sorcerer with hazy eyes. The man was squatting in front of his hut, watching the flies go by, absent-minded. The ritual required a little bottle of rum, a few packs of tobacco and his acceptance to come along for the day. The fellow turned out to be a bit on the greedy side, expecting an exorbitant price for his service—an issue not to be taken lightly.

“Gargantua” cave

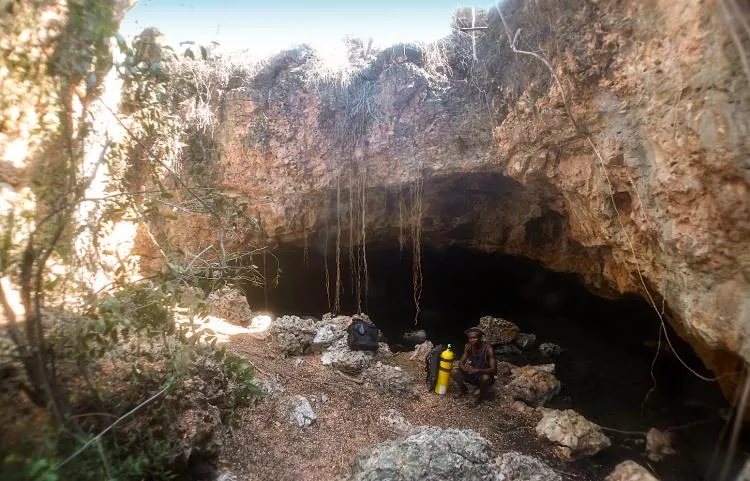

Simply because he was born there, my Mikea guide knew the forest like the palm of his hand. We trekked into the spiny bush, beyond a stand of baobabs, to a collapsed sinkhole partially covered by vegetation. A conspicuous depression, ten metres down, opened up rather wide into a stony arch, with hanging roots in front of a gaping mouth of an entrance. I named the site “Gargantua” cave. In the dim light, an underground lake laid still.

At its far end, I submerged gently into a long winding tunnel with an oval shape. At a depth of 10m, I passed the skull and jaws of a dwarf horned crocodile, resting on its side on fine brown silt and grinning with red teeth. The striking colouration was due to the presence of oxides in the water, among which was iron.

A bit farther on was the spinal cord and vertebrae of the reptile. On the side slope below a ledge, my eyes fell upon a full horned crocodile skull, almost totally covered in silt and hardly visible. Finally, in a pit-like hole, the beam of my torch spotted an accumulation of small bones around the remains of a crocodile jaw. These small bones belonged to bats and small lemurs.

Crocodile lair

“Gargantua” cave was a crocodile lair in the Holocene times—around 11,700 years ago—when the Nile crocodile had not yet made it to Madagascar. The climate must have been very different then—wet, lush, tropical, and not as arid as now. Such was the case in the late Pliocene. This was a freshwater species, not saline, preferring a habitat away from the coast.

Scientists brought to light the fact that it had functional lingual salt glands, secreting excess salt. Of the Osteolaeminae family, the ancestor originated in Africa in the Miocene. A new species, Crocodylus anthropophagus of the Pleistocene, which had similar small horns and a deep snout, was discovered in 2010 in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, in tuff formations dating 1.8 million years old.

A miniature horned crocodile from the Quaternary was also found on Aldabra Atoll in the Seychelles in 2006—meaning to say that the dwarf horned crocodile did cross the 400km wide Mozambique channel on its own. What brought on the extinction of Voay robustus, the dwarf horned crocodile of Madagascar, remains anyone’s guess.

The walls of the tunnel were visible on both sides. A restriction appeared at a depth of 14m, under a low ceiling, with a silty bottom. To avoid getting stuck and in fear of a black silt-out, I chose wisely to turn around… “Another time,” my inner voice said.

On the way back to the 4x4, some Mikea men were wandering about. They showed me another spot and took me off the trail and into the bush. A moment later, we stood in front of a star-shaped hole in the white and pink limestone, which plummeted into a black void—a vertical solution pit. Could it open into a chamber below? That was creepy. “How do you expect me to get down there?” I coughed, with an uneasy smile. My guide Same shrugged, amused like a naughty kid.

Returning to Tulear

A year elapsed. In May 2017, the wet season was over, and conditions were dry again. I was thinking that I had to go with twin tanks from now on. In anticipation, I had brought two of my 80 cf Luxfer aluminium tanks in a suitcase, all the way from the Galapagos Islands to Tulear. Available for hire in Madagascar were only steel tanks, which were stubby, impractical and too heavy for double-tank dives. Backmount diving was not an option, since there was no way I could squeeze through restrictions with that configuration. The viable alternative was sidemount. With that in mind, I signed up for a Full Cave and Sidemount course in Yucatán (Mexico).

Back in hot Tulear, I was as excited as a little kid, with my brand-new X-Deep harness, Maxflex hoses and the lot. My yellow helmet—to support a backup light—made me look like a middle-aged clown on a crusade. With the four-wheel-drive all packed, we headed off.

The first stop was one hour away. A new tar road meandered along the seashore over rolling sand dunes overlooking fringing turquoise green lagoons, where colourful Vezo sailing canoes drifted timelessly in the breeze. Postcard perfect.

I wanted to fill the Luxfer tanks and hire some steel tanks as well, but I was in for a devastating surprise. The aluminium tank was already connected to an old rusty compressor in the backyard of a beach house, when “puff!”—I heard the hissing sound of air escaping the valve.

Blistering barnacles! it wasn’t the O-ring, but the burst disk, now useless. No replacement could be found anywhere. No aluminium tanks either. My “sidemount” plan was falling apart, abruptly. It would have to be a single-tank dive again…

After a long day on sandy dirt trails, the Mikea guide welcomed me with a big smile. For the sake of sanity, I chose to avoid the village chief, and bypass the mad sorcerer, who might cast me the evil eye.

Revisiting “Gargantua” cave

Plan One was to dive “Gargantua” cave and negotiate the low ceiling restriction. I managed successfully by slipping through sideways. The tunnel widened up dramatically, with a conspicuous bend to the left, and reached a T-junction, where it sharply split into two branches.

Depth was now 17.4m. I took a right turn for another 20m or so, and gazed at a stubby stalagmite, before another bend to the left. The ongoing tunnel was large enough for a train to go through. We called it off for now. Maximum dive time was 54 minutes.

On a successive dive, I explored a side tunnel, with a flattened neck, on the right of the “Gargantua” cave entrance. It was a silty chamber, where I soon laid eyes on more bones and a crocodile’s lower jaw, with a femur delicately resting inside! There were some blind cave fish, which were blue and black in colour.

At the end of the day, it felt good to be back in the comfort of a cosy bungalow—at peace with nature. Facing the Mozambique Channel, with a “sundowner” in hand, one could not help but reflect on the cave experience.

Cave diving solo

As a solo cave diver, you need to have guts, because you cannot rely 100 percent on self-confidence. To put it bluntly, you are on your own in the dark. You cannot depend on the emotional support of a dive buddy or get assistance in a tricky situation—i.e., lack of air, getting stuck or ultimately getting lost. You need to be fully aware of your equipment’s reliability, control your breathing, remain calm under any circumstances, and trust that everything will go well.

It is an instinctive feeling to be afraid of the dark, to not go into holes. The farther you venture away from the entrance, the hairier it will be to return, should an emergency arise. Subconsciously, playing with your life does scare the hell out of you. Somehow, as if pulled by a magnetic force, you still go for it, for the adrenaline rush. Like a drug, it fuels your imagination.

Deep down, you are wild at heart, an explorer to the core. This is what you crave to push your limits. You set yourself apart, as a free spirit, to evolve into an unknown dimension. Sure, your desire is to bring back images, as a coveted prize, to prove to yourself and others that you are not dreaming.

Although hidden from view, the cave is real—a fantastic world frozen in darkness, which tells the story of geological times. Millions of years in the making, it is just mind-blowing. As in Alice’s looking glass (in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland), it is a window into palaeontology, a peephole into life as it once was—a living museum of natural history. It is accessible to the chosen few who dare to pass the threshold of fear. “You are mad!” I am often told. “Controlled folly,” I would say, in correction.

Revisiting “Ali Baba” cave

In the early hours of the next morning, a Malagasy suimanga (sunbird) came by, collecting the pollen of a hibiscus flower. The day started out bright, and the sun promised to be hot. It would be “Ali Baba” cave again today. My resolution was to go as far as possible, beyond my previous record, on a single tank.

With a last breath of fresh air, I bowed down under the humbling, lentil-shaped gateway to the “sauna” of the cave. Steel tank on his back, the porter followed suit. With my headlamp already low on power, I switched to the back-up torch on the helmet.

Holy smokes! A 1.5m long snake appeared on the slope right in front of me. Endemic to southern Madagascar, it was a magnificent Dumeril’s ground boa (Acrantophis dumerili), which sat stoically in wait to ambush passing bats. It was reddish-brown and silver in colour, with a diamond-shaped pattern on its sides and back. The boa remained oblivious to our presence, and we proceeded swiftly downhill.

I submerged, following the same route downhill, squeezing through the restriction, passing by the bulbous-headed, missile shape of the stinkhorn mushroom-like stalagmite, with a long extravagant overhang of stalactites behind it. The main tunnel looked like a capharnaum (mess) of broken rocks.

Beyond the great curtain of “organ pipes,” hanging above the round window of the cave, I proceeded farther, through a couple of restrictions, until I stumbled upon a dead end, where I found a small, rounded chamber displaying ripple marks in the sediment. To my surprise, the way stopped here, at a depth of 24.5m, just 19 minutes after I had started the dive. My pressure gauge indicated it was time to turn around.

On the way back, I froze in awe before an amazing double pillar above a “fountain” of stalactites under an incredible ceiling full of helictites, all in white and bluish hues. Back in the lake chamber with its albino-white cave fish, I was filled with inner peace from the achievement of the day. At the 5m deco stop, a blind fish approached, staring at me with its vestigial eyes. Surrounded by “dantesque” pillars, Same turned on his light as I surfaced, glad to see me back and ready for help. Before exiting, I saw a baby Dumeril’s ground boa slithering on the rubble slope. Fresh air was a blessing.

Big clouds drifted in the blue sky over the weathered karst plateau covered with Euphorbia stenoclada trees (silver thicket), with their thick spiny leaves. A parched land under the sun, it was. Making a stop by the well, the porter and driver went to recover a rather heavy, homemade rope ladder, which needed to be carried with a long stick on the shoulders.

The night before, my host had suggested that I should use it to explore the star-shaped hole discovered in the bush one year ago. “It is 9m long; that should do,” he reckoned. I referred to this star-shaped hole as the “Pit Hole.”

Last dive at “Gargantua” cave

The goal was now to explore the right branch of the tunnel after the T-junction. The camera would help me record the timings, through photos of key points, which would aid in figuring out the time that elapsed between all the landmarks and the total dive time. Practical. The low restriction was negotiated in 10 minutes, the T-junction in 14 minutes.

Onwards, the right tunnel was big and oval-shaped. A funny stalagmite with a rhino horn appeared on my right, then a gigantic pillar rose to my left. It was maybe 10m tall. High up, it displayed conspicuous markings left by former water levels, with two dark bands, which reflected extensive periods when the cave lake had a pocket of air above it. The hot humid air had cooked the limestone to nearly black in colour.

Overcoming a short thumb-like stalagmite with two watermarks, the beam of light from my torch revealed an apparent dead end. Somehow, the way led onwards through a funnel-like restriction. With 120 bars left, the voice of wisdom in my head dictated a turn around. Cave depth was now 18 metres.

Upon return, I had a glimpse, on the left side of the line, of an adjacent tunnel branching to the left, which I did not notice earlier. Thinking I was on the right track, I boldly went forward. A cluster of ornate stalagmites appeared, with zebra-like markings. Suddenly, I came to a dead end in a round chamber. Stupor!

The manometer indicating 90 bars, I was overwhelmed by fear. Exerting mental control of my breathing, I made a swift beeline back to the T-junction, through the main tunnel, all the way to the crocodile skull. A 13-minute dash! Only then did I know I was safe. A 6-minute deco stop was in order. The torchlight revealed two huge, winged crocodile vertebrae on the side slope. My inner voice whispering: “Next time, sidemount, by all means.” Thrilled by the feat of the day, I swam leisurely into the shallows of the lake, towards the pale blue light of the twilight zone…

Following explorations

I returned in 2018, using a “sidemount” configuration for the first time in “Gargantua” cave. Exploring the left tunnel after T1, I reached T2 and ventured a bit farther, beyond a “shark fin”-like stalagmite, into a tunnel on the right. However, as I made it back into the shallows of the safety stop, I could not deflate the wing properly and found myself stuck to the ceiling. I had to crawl my way back towards the exit lake! A bad joke indeed. Later, I figured out that I had to deflate the wing from the lower back side and not with the front purge.

In 2019, I experienced a dramatic event. I flooded my camera housing on my first dive and that was the end of it. Maybe it was the curse of the cave spirits?

Then, the Covid-19 pandemic arrived. Madagascar was closed for two years. I resumed my exploration in October 2022, rather anxious, considering my former misfortune. My fears were overcome with courage; I pushed into the left tunnel after T2, at 22m. Eventually, I reached T3 through a canyon that would have been 30m deep at least, but I did not descend.

From the original research of early explorers, I am fully aware that the cave system has at least 5km of passages, going in all directions. Although I did my TDI Stage and DPV courses in Yucatán in 2020, I am not foolish enough to venture beyond my capacity and experience as a solo diver. The sole purpose of my dives being underwater photography, I need my two hands. Therefore, I am strictly limited to a sidemount system. “Hard core” maybe, or even an “idiot” to some, I am definitely not a daredevil…