Extending 329 kilometers from north to south, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands have 1,912km of coastline, about a quarter that of India. The continental shelf has a surface area estimated at 16,000km². The coral reef biodiversity here amounts to 5,440 species, 138 of which are endemic.

Contributed by

Factfile

Pierre Constant is an author, photographer, dive master, naturalist consultant and expedition organizer based in the Galapagos Islands.

For more information, visit: Calaolife.com and Scubadragongalapagos.com.

REFERENCES: Wikipedia.org

Some call it Kalapani ("the black waters"}, from the Hindi Kala ("black") and pani ("water"), but to scholars, the word has a much somber meaning. It comes from kal ("the time of death") and therefore Kalapani should translate as "the waters of death". To those convicts who were doomed by the British Empire in the 18th century, it meant transportation to the penal settlement of Port Blair in the Andaman Islands. The first British colony had been established at Port Blair in 1789 by Captain Archibald Blair, but was closed in 1796. A penal settlement was later opened in 1858, to cast away prisoners after the first Indian war of independence in 1857.

Consequently, Kalapani became a place for throwing freedom fighters into living hell. To the Indians, these islands were a sacred place, for it symbolized their struggle for independence. The initial batch of 200 prisoners (aged 18 to 40 years) was exiled on 10 March 1858 and sentenced to hard labor. A number of them were Burmese from Theravada, who had revolted against British rule.

From the very beginning, aborigines attacked the working parties, resulting in a number of prisoners killed. The infamous "Cellular Jail" in Port Blair was constructed in late September 1893. Instead of dormitories, there were individual cells measuring 13.5 by 7.5 feet, designed to keep political activists from communicating with each other. In total, 693 cells were completed by 1909 in the two-story monument, which looked like a starfish with five arms, controlled by a central watchtower.

Forced to perform nine hours of painstaking hard labor every day, political convicts had to produce 30 pounds of coconut oil and 10 pounds of mustard oil daily. For those who failed to do so, punishment was barbaric, with torture and flogging being the norm. Neck ring shackles, leg irons and chains were common adornments here. Particularly defiant prisoners were handcuffed for a week or sentenced to six months of solitary confinement. Self-proclaimed god, David Barry, was a dreaded jailor from 1905 to 1919. “We are here to tame lions…”, he used to roar to the newcomers.

Geography

Located 1,000 kilometers east of India in the Bay of Bengal, 700 kilometers west of Thailand in the Andaman Sea and 100 kilometers south of Burma, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are spread between latitude 6°45 to 13°41 N, and longitude 92°12 to 93°57 E. They represent a group of 572 islands—38 of which have been inhabited by human beings for a very long time.

The 8,249km² land surface is shared between the Andaman Islands (6,408km²) and Nicobar Islands (1,841km²). Two deep channels cut through the island chain from east to west: the latitude 10°N channel between the Andaman Islands and Nicobar Islands, and the Sombero Channel between Great Nicobar and the Nancowrie group.

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake of December 26 [ed.—also known as the Sumatra–Andaman earthquake] induced major topological changes for the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. They are in the seismic Zone V outside the Himalayan belt and have experienced several earthquakes in the past, triggering tsunamis. The earthquakes of 1847 and 1941 created a tsunami that hit India's eastern coast. For aficionados of plate tectonics, the so-called Sunda-Andaman Trench is related to the subduction of the Indo-Australian Plate below the Eurasian Plate. The northeast-moving plate converges obliquely at 54mm per year with respect to the Eurasian Plate.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands are bounded by the Andaman Trench to the west and by the Sunda fault system to the east. Measuring 3,000 to 3,500 meters deep, the Andaman Trench marks the active subduction zone where the Northeast Indian Plate goes under the Eurasian Plate. The island chain acts as a small tectonic plate, known as the Burma micro-plate. The Andaman Sea represents the back arc basin, characterized by the Andaman spreading centre. The tectonic setting results in the development of several thrusts and strike slip faults. The West Andaman Fault (WAF) is the most prominent right lateral slip fault that has continuity all along the islands. This fault extends from Sumatra in the southwest up to the Burma micro-plate in the north.

Consequently, the Andaman outer arc ridge, the right lateral WAF and the Barren volcano—120 kilmeters northeast of Port Blair—are major tectonic features in the region. Extending from north to south in apparent parallel lines, the Andaman and Nicobar ridges are in fact scraped accretions of oceanic sediments uplifted during the Oligocene times. The eastern part of the Andaman Islands is made of highly deformed rocks (ophiolites) from the ocean floor, comprised of Cretaceous and early Eocene ultrabasic volcanic pelagic sediments. The western part of the islands are a prism of Eocene/Oligocene (Primary era) conglomerates—flysch, sandstone and siltstone, with calcareous sediments of the Miocene/Pliocene times.

The Great Quake

At 9.1–9.3 on the Richter scale, the December 2004 earthquake was the second largest in magnitude in the area in 200 years and the third-largest earthquake ever recorded, in the company of large earthquakes such as Kamchatka in 1952 (magnitude 9.0), Alaska in 1964 (magnitude 9.1) and Chile in 1960 (magnitude 9.5). The rupture was 1,200 kilometers long along the subduction plate boundary in the Sumatra and Andaman and Nicobar region, registering a slip of about 20 to 25 meters.

The seismic data showed two phases: 400 kilometers long and 30 kilometers deep along the coast of Banda Aceh in the epicenter, with a 600km rupture occurring along the Andaman Islands. The thrust motion had a gently dipping plane towards the northeast. A sharp change of 1.2m in the mean sea level was recorded in Port Blair after the earthquake. A 10-meter-high tsunami wave hit the Little and Main Andaman Islands. The tectonic subsidence of the eastern coast was conspicuous, with submerged beach and forested areas along the eastern coast of South Andaman. Uplifts of land (maximum of three meters) were noted in Mayabunder and Diglipur in the North Andaman.

The eruption of a mud volcano created a surprise near Jarawa Creek, at Baratang Island (Middle Andaman), 105 kilometers north of Port Blair. On December 28, only two days after the devastating earthquake, the Barren Island volcano erupted east of the Middle Andaman Island. Lying within the Burma micro-plate, it has sustained its activity since then.

Born from an eruption in the late Pleistocene, Barren Island has a diameter of 3km and a land surface of 10km², culminating at an elevation of 335 meters. Contrary to common belief, it is not barren; it is covered with a lush green jungle and is home to 13 species of birds, seven species of mammals, nine species of insects and 10 species of butterflies. A probable shipwreck in the area also brought goats, which have since colonized the island.

History

Known to the Chinese, Indians, Burmese and Thais, the Andaman Islands were visited by Marco Polo in the 16th century. Long before the British made their first claim, the islands were inhabited by aborigines, headhunters and fierce cannibals. Despite their geographical isolation, it is rather peculiar to note that recent DNA matches indicate a direct link with the pygmies of southern Africa.

The five foraging communities here are dependent on aquatic and terrestrial resources. Classified as Negritos, the Jarawas (south Andaman), Greater Andamanese, Onge (Little Andaman) and Sentinelese are short in stature, characterized by broad heads, relatively broad straight noses and dark skin. Two other distinct groups are classified as Mongoloids: the Nicobarese and the Shompen, who are characterized by yellow brown skin, straight hair, oblique eyes and prominent cheekbones.

The migration routes of the Negritos were most certainly from Malaysia, Borneo and Sumatra. In the Andaman Islands, the tribes were hunter gatherers, whereas in Nicobar, they were mainly horticulturists and herders.

Bows and arrows, adzes, spears and harpoons are still commonly used for hunting and fishing. Turtles, fishes and dugong are on the menu. Single outrigger canoes and rude crafts like dugout canoes are favorites for hunting on the sea. The Onge of Little Andaman collect honey by climbing trees. The Jarawa tribe of South Andaman build round dwellings made of leaves, which act as community huts. Skulls of wild pigs, decorated with cane strips, are displayed inside huts as trophies.

For the Greater Andamanese, the scarification of the back in three vertical rows of horizontal cuts was in practice in the late 19th century—reminiscent of the scarification (initiation) rites of the Crocodile men of the Middle Sepik in Papua New Guinea.

After the colonization of the islands in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Great Andamanese, Onge and Jarawas stayed away from the white men and civilization altogether, until recently. The Great Andamanese and Onge have now accepted outsiders. The Nicobarese have integrated them as well. The once-ferocious Jarawas are becoming friendly. However, Shompen still avoid contact, but are not hostile. Numbering a mere 39-strong on Sentinel Island, the Sentinelese continue to refuse contact and are resolutely hostile to strangers who try to land.

The journey

The daily domestic flight from the Indian mainland connects Chennai to Port Blair in exactly two hours. There should be a time difference of one hour, but, against all odds, the Andaman Islands run on Indian time. One experiences a ridiculous sunset at 5PM and a disturbing sunrise at 5AM! A light rain welcomed my landing at the South Andaman airport. I was whisked to the pier by a nervous driver who did not want me to miss the ferry. The MV North Passage would leave at 2PM to Havelock Island. It would be a crossing to the northeast (lasting two hours and 15 minutes) on a calm sea. It was compulsory for foreigners to report their Andaman visitor’s permit upon arrival.

For over 20 years, Havelock has been the hub of diving activities on the Andaman Islands. To my bewilderment, I found out that there are now 64 dive centers in operation. While the islands are spread out on a large scale, dive shops and attached resorts are all concentrated on a tiny stretch of land east of Havelock. Vikas, the dive manager of Dive India is very professional. He introduced me to the ebony dark Angshuman, a bright convivial instructor. I also met Rahul, the inhouse marine biologist-cum-instructor. All smiles, Johnny, the Karen divemaster, with 15 years of experience of the area, would be my guide. “You’ll be in good hands!” I was told.

Accessible through a small strip of coconut trees, the nearby beach is a mix of sand and grey silt. At low tide, the reef flat extends quite far out to sea. Awaiting the morning departure was a dungi, an elongated Burmese boat with an inflated bow, which served as the local dive craft with a lot of character. The mid-part, acting as the passenger cabin, comprises a rounded half-tubular bamboo frame, and is covered with a black plastic sheet for sun and rain protection. The dungi is propelled by an old rusty 20hp inboard motor that goes “tuff-tuff” like a steam train. The snorkel-type exhaust pipe exhaled a cloud of black smoke as we cruised at a snail's pace.

A non-conspicuous shadow at the stern, the slender Karen boatman stood up like a sentinel on watch, steering the boat skilfully, clasping and maneuvering the handle of the boat's rudder between his toes. Amazed, I gazed at him as he stared at the horizon, oblivious and undisturbed. Numbering 3,000, the Karen had been introduced to North Andaman in the mid-19th century and are now concentrated in Mayabunder. Originally hill tribes from Burma, they have became sea Karen, being involved in fishing activities, while also farming rice paddies traditionally.

“Unfortunately, we experienced a very serious coral bleaching in April 2010, due to global warming,” warned Vikas, giving me advance notice. “The water temperature rose up to an amazing 34°C, and every bit of coral was dead down to 10 meters. Fortunately, at depth, it is still all right.”

Dive sites

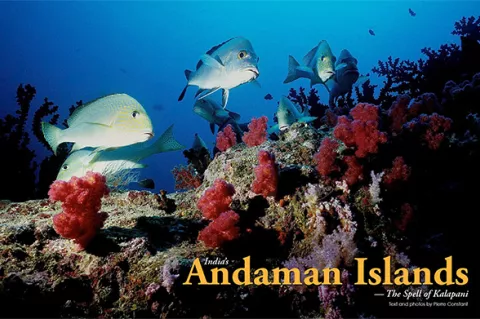

Johnny’s Gorge. Named after divemaster Johnny, Johnny’s Gorge was one of these fountains of life, sparkling and teeming with fish. At a depth of 25m, I met a school of striped blue and gold Bengal snappers, hovering over several enormous barrel sponges. Various species of sweetlips mingled around cleaning stations. Marbled groupers of a fair size had made their home here.

An inquisitive giant grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus) 1.5 meters long, approached me for a closer look, with a flock of yellow black-striped pilot fish at its nose. The big fellow was rather shy though, and turned around swiftly to flee.

Some dogtooth tunas and spotted queenfish darted by on a hunting spree. A cool Napoleon wrasse drifted like a dark cloud in the distance. Gorgonians and soft corals dotted the seafloor, sulphur yellow hanging corals carpeted the rocks. It was pure enchantment, and a good indicator of a healthy reef in the deep. A whitetip reef shark rested in peace on the sandy bottom, but would not allow a close visitor. It took off with a flick of the tail.

Minerva Ledge. The second dive at Minerva Ledge was a shallow one. Sadly, it was not really worth a mention, being scraped and bleached out. Nevertheless, I came across the endemic spotted Andaman sweetlips, whitish with big black spots. When we were at the safety stop, Johnny pointed out to what looked like a mobula ray, cruising along the bottom. I swam toward it and found that it had a very small tail. Perhaps it was a baby manta ray. Frightened, it zoomed up towards the surface in a spiral.

SS Inchket. The SS Inchket was the wreck of a cargo with a steam boiler engine, which sank in 1952 and completely broke apart. Starting from 7m down to 18m, the dive site had a surface current, fading at depth. Visibility was poor (due to its proximity to the mainland) with lots of particles in the water. The fish life was plentiful, with lots of snappers, sweetlips, groupers, blue ringed angelfish, giant jacks and big eyed jacks swimming in schools. I attempted a few penetrations inside the wreck and towards the propeller, startling a giant grouper that disappeared into the darkness of the hull.

Dickson's Pinnacle On a clear sunny day that made one think of paradise, I hopped aboard the dungi Bullshark. The sailing time to Dickson’s Pinnacle on a flat sea was about an hour to the southeast of Havelock. We dived on a large coral bommie that reminded me of "Magic Mountain" in southern Raja Ampat. It was covered in soft corals, barrel sponges, hanging corals in sulphur yellow colour, whip corals and feather stars. A large turtle hovered on top, with a mixed school of Bengal snappers and paddletail snappers hanging around at the sides. Bluefin jacks, giant jacks and dogtooth tunas cruised at speed. Another giant grouper came out of the blue and zoomed up to me for a closer look. The visibility was excellent. A smaller pinnacle revealed itself nearby, covered with Tubastrea micrantha or black sun coral with green tentacles, which look like Christmas trees surrounded by clouds of anthias. “To the southeast, there is a stream of bubbles coming out of the seafloor,” explained Johnny. A clear sign of volcanic activity, for sure.

Diving with an elephant. Beach #7, on the west coast of Havelock, is 15 kilometers away from the main bazaar. There, the stretch of white sand is mind-blowing, wide and long, breezy and fringed by an authentic jungle feel. Big trees with buttress roots, large ficus with hanging roots that dig into the ground, leafy Terminalia trees [ed.—or Indian almond trees] that attract bats at night. A number of Indian tourists strolled along the seashore, taking family pictures, for this was indeed the ideal setting for a postcard at sunset. Today, however, the sun disappeared behind a cloud layer, before its dramatic plunge into the Bay of Bengal. A stone's throw away was the location of Barefoot Scuba Dive Centre, where people could, upon request, dive with Rajan, the swimming elephant.

Over 20 years ago, working elephants were the norm in the Andaman Islands, used in the logging trade. This activity has been officially banned since then, and the elephants are now retired. Well, except for Rajan. Once in a while, it posed stoically and displayed in the water for the tourists and amateur photographers willing to pay the mere amount of US$1,000 for an outing, shared with four other persons. Can you believe that? I almost swallowed my tongue! You may agree that this is a shameful rip-off, but you'd be surprised—some people do pay the fee, including so-called professionals!

Jackson’s Bar. Last but not least was Jackson’s Bar, named after divemaster Johnny’s third brother. Johnny’s Gorge, Dickson’s Pinnacle and Jackson’s Bar are key dive sites in Havelock. Located at a depth of 20m in clear water, this flat rocky reef makes a shelf that slopes down to 30m on sand. The rock is literally covered in barrel sponges, soft corals, with usual fish life.

A school of rainbow runners darted by, mid-water, while Bengal snappers and gold-spotted sweetlips gathered in clouds, hovering above the bottom. A cute barramundi, posed next to a white sponge, where a large Java moray eel peeked out from below an overhang. Oblivious, a potato grouper dozed off on the seafloor. With the speed of lightning, a school of flashy silver yellowtails swirled by in a showy display, out of sheer curiosity. I finished up my film before the end of the dive, and missed out on a large banded sea krait sleeping in a crack!

More than a dive location

A visit to the Andaman Islands is not only about beaches and diving, but to a certain extent about history and culture. For a bit of sightseeing it is possible to travel by road from Port Blair up to North Andaman, firstly along the Great Andaman Trunk Road—crossing the Jarawa tribal lands—to Rangat, Mayabunder and Diglipur (the end of the road). Alternatively, one can catch a ferry from Havelock to Rangat, via Long Island, three times a week. Heading south from Havelock, a daily ferry sails to Neil Island, a traveler’s hang out, away from the crowds. Dive India has opened a new resort and dive center on Neil in late October 2011, giving access to new dive sites in pristine locations.

The Wall. Past the small lighthouse west of Havelock, an underwater ridge extends north towards Sir William Peel Island. Named The Wall, this dive site is actually the continuation of Havelock’s dorsal spine, crested with jungle, which goes underwater. Rock formations are conspicuously tilted towards the east. Divemaster Angshuman, covered in tattoos—from Bob Dylan to a pirate ship, a Buddhist mandala, a flying dragon and Jim Morrison (among others)—gives his lively briefing on the Dungi.

We waited for the 8:30AM ferry from Port Blair to sail by, before we jumped in. The visibility was far from flash, even murky, but white bushes of black coral were thriving everywhere, as well as gorgonians, cushion stars and different species of sea cucumbers: black, pink and the Thelenota sp. loafbread type. Not to mention, there was a leopard sea cucumber (Bohadschia argus) that loved to regurgitate its stomach in white sticky filaments, if molested. Johnny promised me he would find a harlequin ghost pipefish, but the rascal remained absolutely elusive. Instead, he discovered a cute Phyllidia ocellata nudibranch, black with yellow knobs, and an exquisite Halgerda batangas nudibranch that was on the translucent side, with pink dots and salt and pepper gills. Mimicking a death skull, a huge stonefish played hide-and-seek in a crack.

The highlight of the dive was a charming Hiby's lamellarid (Coriocella hibyae) a sea snail of the Velutinidae family, found at 22m depth, with five pencil-like appendages. Greenish brown with pinkish specks (which looked like algae inclusions), the velvet snail was neither a nudibranch nor a sea slug, and fed on a sponge.

On the bigger scene, dogtooth tunas were ever present, plus an entertaining mixed school of golden striped jacks and goatfish were foraging in the sediment.

Finally, at a depth of six meters, I came upon the extremely rare sighting of a small colony of spine-cheek anemonefish with abnormal yellow bars (outlined with white) across the sides. One sees these clownfish usually with white bars, and for me it was definitely a first. For a moment, I wondered if they could be endemic to the Andaman Islands, but ichthyologist Gerry Allen had already reported them in Sumatra.

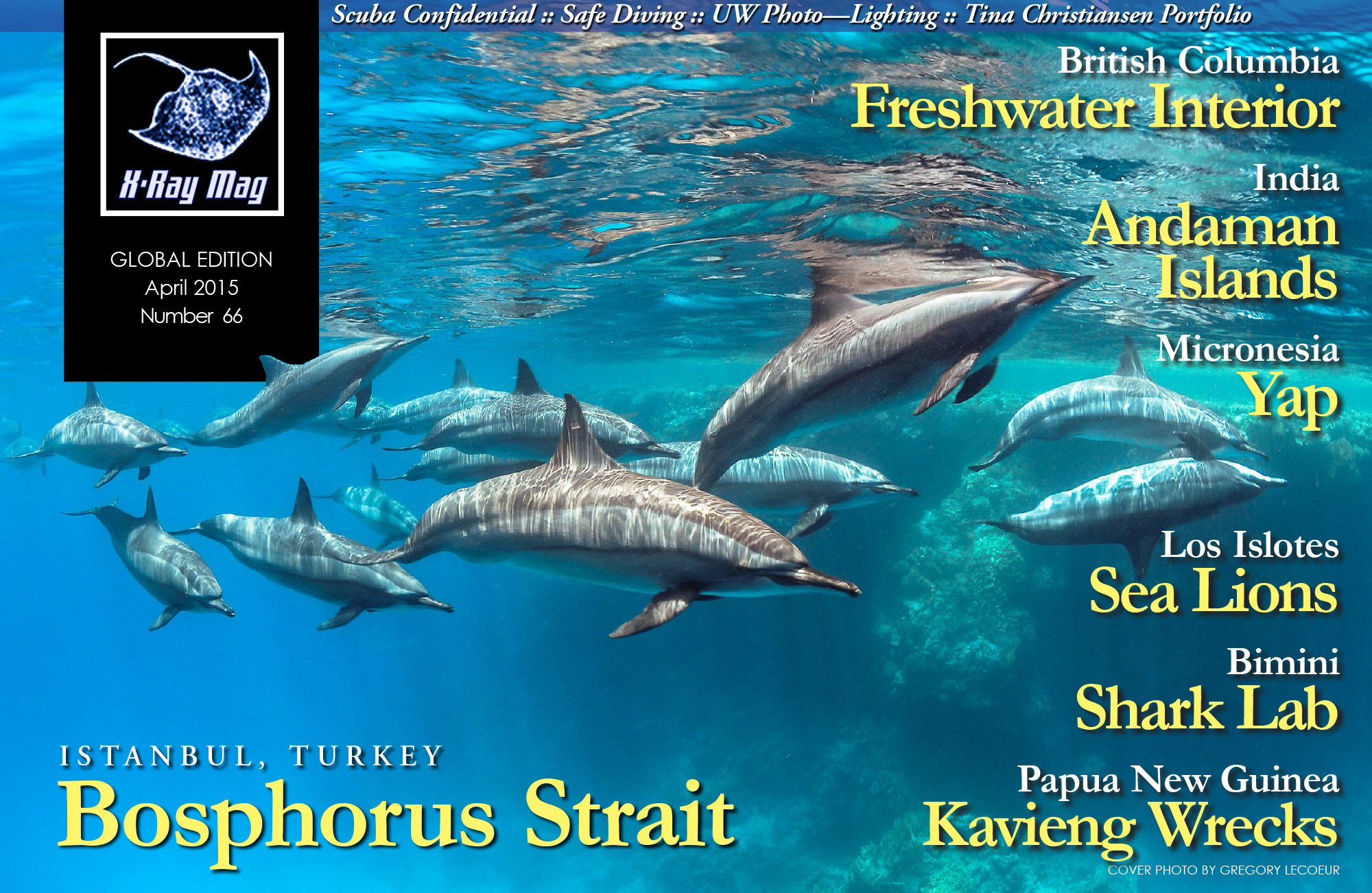

Dreaming

The dream of divemasters and dive instructors Vikas, Rahul, Angshuman, Johnny and others, would be the emergence of a liveaboard in the Andaman Islands. “Imagine, we would be able to reach remote dive sites, like Barren Island, Narcondam Island, pristine reefs… and there are so many of them! If only the authorities would allow access…” they mused, as their eyes opened wide, alluring smiles on their faces. Then one can imagine from the dreamers' vision that the magical, yet unknown parts of the Andaman Islands are still out there to be discovered—alive, in the deep blue, waiting to be revealed. ■