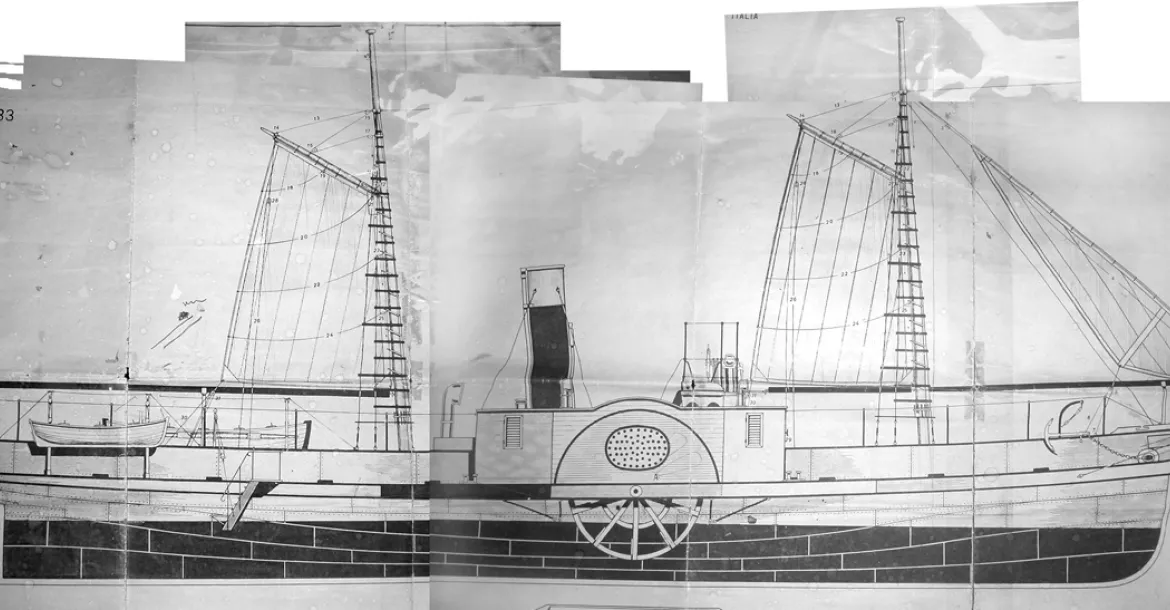

Like every grand tale of shipwreck and lost treasure, the story about the Polluce has it all. A paddlewheel steamboat shipwrecked in 1841, it is the centrepiece of a drama spanning more than one and a half centuries and has all the necessary ingredients: drama and tragedy, greed and crime, passion and politics. And it is still ongoing. Polluce is about to be excavated once more as this story goes to press.

Contributed by

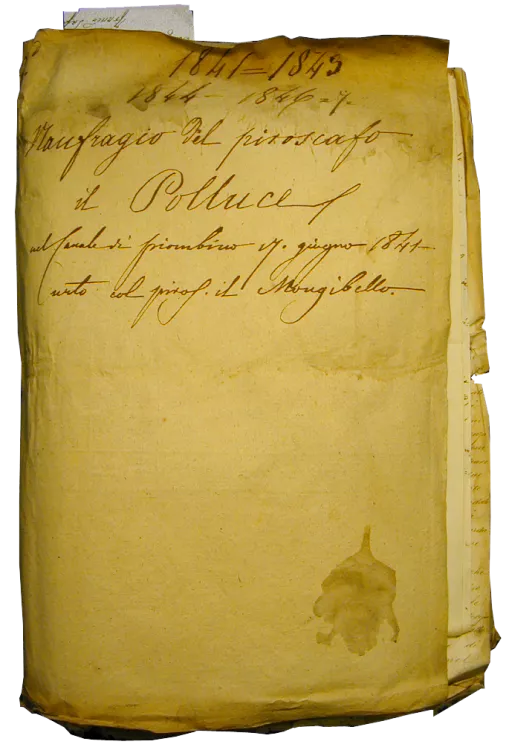

The story isn’t complete either by including the following inquiries and legal proceedings, which took place in Livorno (Leghorn) in the years 1842 to 1846, right in the middle of a turbulent period of history when European nationalism flared up and new states were born or unified including modern Italy.

We have spanned one and a half centuries to include a clandestine excavation of the wreck and illegal removal of the treasure in the 21st century as well as an international scandal and a police matter which reached into several European countries.

Rise of nationalism

In 1841, every little kingdom, duchy or territory in the politically fragmented area around the Tyrrhenian Sea seemed to, maybe not surprisingly, have some stake or claim on this wreck and it’s precious cargo. In that day and age, there were no such notions as territorial waters or international treaties governing legal matters pertaining to the seas. A ship’s owner had little or no protection nor was there a supporting legal framework in regards to salvaging a lost ship or its cargo. Indeed, this was also the case of the Polluce and it’s owner, one de Luchi Rubattino from Genoa.

First attempts

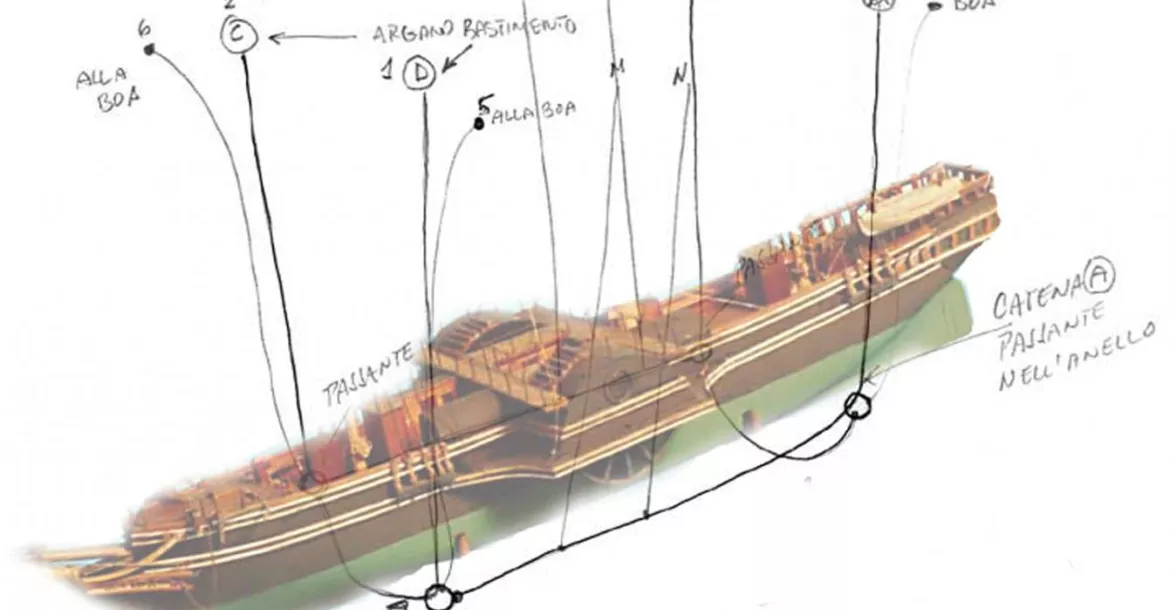

Following the loss of his vessel, de Luchi Rubattino desperately staged several salvage attempts. However, the wreck was lying far deeper than any previous salvage work. Attempting to salvage the wreck of the Polluce was an unbelievable enterprise at the time—it was the first time anyone had tried to go so deep. After two failed attempts, de Luchi Rubattino predictably ran out of money a gave up. He spent 500,000 lire to buy a brand new boat and salvaging attempts cost up to 470,000 lire.

Also as an interested party, we have the king of Sardinia for whom it was its most important trading vessel and the king of France who supplied some of the equipment for the salvage attempts including some heavy lifting chains which can now be found at the naval base of Toulon in southern France. A report of these recovery attempts, in the form of a 48-page booklet dated 1841, is then passed down history from a colonel serving the Archduke of Tuscany.

21st century visitors

It is armed with these historical records, obtained from a Parisian investigator of historical documents named Pascal Kainic, a group of eight English divers from East Anglia (a county in eastern England also known as Norfolk) arrive in Genoa in the spring of 2000 - David Dixon, Jerry Sullivan, Kerr Sinclair and Nicholas Pearson and some others.

None of them had any previous experience with salvage work and only two had previously worked at sea at all. They did, however, seem to know exactly where the wreck of Polluce is located and how to get there. One of them also seemed to be the manager of a salvage company, curiously enough.

In Genoa, the group charters a supply vessel with a crane and an excavator bucket from the Genoese company Technospamec and hire in an Italian crew. The charter is for three weeks against a fee of €190,000. They set sail and head right for the designated area where they set out their marker buoys.

Using a ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle) with a video link they search the bottom and try to steer the excavating bucket onto the wreck. With this crude tool, they break up the wreck to get to the cargo and the treasure. During their 21 days at sea, they manage to bring up and onto the deck of their vessel 1400 tons of mud and scrap iron.

Meanwhile, the Italian crew were kept completely in the dark. Their access were restricted to the foredeck and they were forbidden to see or interfere with what was going on with the excavation and what was loaded onto the aft deck.

40 tons of Lead

On March 1. they returned to Genoa. Here they unloaded 40 tons of recovered lead, gave the crew some silver coins and disembarked to return to England without a hint about any treasure to anybody. Nobody knew what really happened.

Back in England, however, the English divers celebrated their amazing adventure and gave interviews to the local daily paper of Great Yarmouth. Once in the headlines of the newspaper, the cat was out of the sack as it would soon enough come back to haunt them. Another interesting chapter in the Polluce story was about to begin.

Who and when?

But how did they know about the content of the Polluce in the first place? And who supplied the position coordinates?

Who made the necessary investigations in order to locate the wreck again after so long time – and when? Polluce was just a single wooden hull 50 meters long lying at a depth of 103 meters and there was no mention of this ship in the national and international nautical books or databases.

The auction

The treasure was put up for sale at an auction held on June 21 2001. at the auction house of Noonan Webb in London. It was a precious collection of 2000 silver coins, 311 gold coins, diamonds and jewels and silverware as well as a cup from a cabinet were meant to be put up for sale . If they had sold all they would have realised more than €400,000. However, it did never come to anything of the sort.

On the day before, on June 20, the Metropolitan Police’s department of antiquities arrived on the premises and put a halt the auction after being informed by the Italian police. In the following statement to the press, the police said they have received information that the artefacts has been illegally recovered from Italian waters and taken to England. The police seized the collection while the astounded producers insisted that their permission certificates from the Italian authorities were in order. In a sense they were.

The permissions were indeed issued to their company but as the policemen soon enough pointed out the permission referred to another wreck, the Glen Logan, and to the recovery of aluminium ingots. Furthermore, as the Glen Logan was sunk in 1916 by a German u-boat off the island of Stromboli near Sicily no less than some 460 miles away this was certainly no small error. Everything was subsequently taken into custody and the four adventurers were first charged and then released.

According to Scotland Yard, they have not paid a single fine at this point in time.

Returning the treasure

On 10th October 2002, Vernon Rapley, the Scotland Yard detective who seized the treasure handed it over to police officers from the Protection Patrimony of Florence. But was it all of the treasure or was it only a small part of it? Subsequent attempts to locate the four for further questioning has been unsuccessful, their telephones were not answered and they no longer lived at their known addresses.

The local press were convinced that the group had a financier as the divers were unskilled. One of them, David Dixon, has previously been associated with offshore jobs but the others, from what is known, have never carried out work with wrecks.

Comex

May 8. 2003. The world-renowned French salvage company Comex’ vessel Janus arrives at Porto Azzurro on Elba to search for Polluce. The owner legendary Henri Delauze is aboard. During searches in a darkened room behind the shoulders of the helmsman four men are seated along a wall of blue screens. Sophisticated equipment controls the ship with millimetres’ precision and enable the men to home in on the exact location where the Polluce is found. It is on the opaque sonar screen the site is first visible. First small, then the location spreads across the monitor.

On edge

Delauze stands up nervously. Takes a close look at the screen. Walks around agitated. Then sits down. The previous visitors have disintegrated and destroyed the wreck and left nothing it seems. The question springs mind: How could the English possibly know about the wreck? Backtracing events the first scan of the wreck was dated June 1995, when Delauze identified it for the first time.

On this scan, the classic silhouette emerges clearly. The hull is easily recognised and it is even possible to locate the deep gash in the flank produced by the bowsprit of the Neapolitan steamboat Mongibello which rapidly sent it to bottom. This scan and a report were sent to the Italian authorities, presumably the Coast Guard in 1995.

Not on the records

After studying the case for many months, I now know nearly everything about this shipwreck and I have a good idea about what might have happened. When Henri Delauze filed his report on the find with the Coast Guard 1995 it is not duly processed. Consequently, there is never any information about Polluce on their record and it is if it doesn’t exist. How the English group is able to obtain this information is a question open to speculation.

A well-planned action

This is what I have been able to put together: David Dixon, Jerry Sullivan, Kerr Sinclair and Nicholas Pearson arrives from Norfolk, England, to Puerto Azurra on Elba to have the adventure of their lifetime. They knew perfectly well what they were doing and where they were heading even though they tried to give a different impression. They clearly knew that they were in the territorial waters of Italy carrying out an illegal excavation but they have prepared well.

Apparently, all seemed to be clear and papers in order. The authorities just never checked them properly. Usually, the Coast Guard takes months to evaluate documents and issue excavation permits. But in this case, an excavation permit was issued within a couple of days. How was this possible? Nor did they seem to wonder, as the local press pointed out afterwards, that the chartered supply vessel was anchored in a completely different position and was equipped for a completely different sort of excavation than the one they had permission to do.

Possible explanations

The Polluce was already a famous treasure wreck for many treasure hunters in Europe. But the authorities had no knowledge of it and for them, it was a ship that did not exist. Nigel Pickford lists it as the treasure of Pollux in his authoritative Treasure Altas, so it is well known. However, there has been much confusion about the names Pollux and Polluce. Pollux has to a large extent been the one that got stuck in the minds of people but wrongly so.

The Pollux is a vessel that was lost at the beginning of the 1800s. One reference tells that Ferdinand IV, King of the Two Sicilies, fleeing Napoleon’s advancing forces as they were invading Naples, loaded his treasures aboard an English sailing ship, and sent it northwards, towards a friendly port. But when the sailing ship passed Elba and was seized by French ships, it preferred to sink itself sending the gold of the king to the bottom.

According to legend, this is a shipwreck of great riches, gold and pearls and one carriage of gold. The legend also places the shipwreck between 1804 and 1806, but the dates are certainly mistaken as the king of the Two Sicilies were not allied to Naples in those years.

This legend in combination with errors in dates and places is what upsets the searches that the Italian police carried out at sea after Scotland Yard had returned the precious material. After one long such search, the police officers locate the remains of the wreck which they investigate with a ROV and hastily establish that it is a Spanish ship with sails.

Misidentification

But there are some details that don’t ring true to me. Among the artefacts seen on bottom are for example a jar of mustard which raises a red flag. This particular jar of mustard was a very particular and expensive brand - one that would very unlikely have been aboard any Spanish sailing vessel at the time. But very possibly on a vessel fleeing with a treasure.

Going over the other artefacts on the bottom including the large quantities of iron soon made it clear that this was no sailing ship. In addition, the list of artefacts given back from the Metropolitan police made it perfectly clear that the wreck had to be younger. Of the 2311 coins on that list, a few silver coins were from 1799, but the others were coined between 1800 and 1830, so the shipwreck must at least be younger than 1830

The treasure

A news clip from the French daily paper Semaphore of Marseilles dated June 23rd 1841, five days after the shipwreck, which happened on the 17th at 11.30 pm, states quite specifically that onboard were 70,000 coins in silver and 100,000 coins in gold which was the property of four rich passengers. The Contessa de la Rocca even brought a golden carriage.

The French media covered the event quite intensely for more than 15 days whereas the Genoese daily hardly mentioned it – a 10 line note on the first day was about all the mention the Italian media cared for. The head steward aboard the Polluce was a gentleman by the name J. Jacques Thevenot.

He was from Marseilles and together with others, 8 sailors were repatriated with the help of the French Consul in Livorno. And this head steward knew very well what was on board as he had witnessed the turn of events firsthand and gave a detailed account that was entered into the records of the time.

The preparations

The treasure hunters, therefore, knew that this wreck had an indeed precious cargo. All they had to do was obtaining the right documents from a historical investigator. But first, the quartet made another operation. Thanks to a backer they first reconstructed Reasdom Beazley a once world-famous salvage company which closed down in 1981.

Before they went out of business they had successfully performed over 80 challenging salvage operations retrieving commercially important materials. Their last job was retrieving aluminium from the holds of the Glenartney which were sunk by an u-boat in 1916 in the Channel of Sicily. Then the business was first sold to a Dutch then a German company before it finally was closed.

Buying the rights to a wreck

Nicholas Pearson resurrected Reasdon Beazley after which the group buys the cargo of the Glen Logan from Her Majesty’s Treasure. The Glen Logan being another wreck in the Mediterranean. The cargo consists of tea, rubber and aluminium and is bought for £1,500. Subsequently, the groups also acquire the wreck itself who is owned by another salvaging company, the Blue Water Recovery, for £ 2,000. Now the group owns both the wreck and its cargo.

Being the formal owners they now want to claim their right to salvage their possessions and they file an application for a salvaging permit referring to international maritime law. This is forwarded through the British consulate in Florence. The application is then forwarded through the various bureaucratic channels to the Coast Guard on Elba which then transfers it back to Florence this time to the

Archeological Authority

Nobody notices that the enclosed documents - which is about a salvage permit for the Glen Logan – never mentions the position of the wreck – and the Glen Logan is located down in the central Mediterranean. Nobody notices that attached is a sea chart of the waters off Elba with a mark that very clearly points to a location three miles from the coast.

The island of Elba is found in the Tyrrhenian Sea and not in the central Mediterranean. And nobody connected the dots in so far that the supply ship was equipped with berthing chains only 250 meters long whereas the Glen Logan rests at a depth exceeding 1,500 meters.

The time tool to Coast Guard to process the papers was remarkably short, only a few days. In this short time it was not possible to check all facts and process the papers properly. We can only surmise that they didn’t even read them but just rubberstamped the application.

Before founding their Society and acquiring the Glen Logan, Pearson and his associates purchased from Pascal Kainic - the historical investigator in Paris - the historical documentation about the wreck.

The operation Columbia, as they called it, began the first days of February 2000. But things do not go according to plan. There are mechanical problems to the bucket that end up almost destroying the wreck smashing everything around the large motor to dust. There are days of bad weather and the ship had to returns to port in Genoa for some repairs. In a month they work perhaps seven to eight days.

Destroying the wreck

The excavator bucket is guided by their ROV. The Polluce, a steamboat of wood 49 meters long, 7,30 wide and 3,5 tall lied delicately laid out in the sandy bottom as a small and tender structure.

They must have assumed that the bucket would simply be able to grab all the valuables and haul them safely back to the surface. How wrong were they? In an excavator bucket, the jaws can’t close properly around objects so most of the contents are spilt on the way up as the water run out and the objects just fall back to the bottom.

The booty was carefully logged in a booklet which reveals that the number of coins collected was less than 2500. This is in contrast to the 170,000 coins that the French newspaper claimed was brought aboard Polluce in Naples. However, a French diplomatic document from 1841 mentions the number 70,000 which indeed casts doubt where there was another 100,000.

Paid in coins of gold

When the group returned to England in March 2000 they didn’t settle the account with the off-shore company Tecnospamech of Genoa from which they chartered the supply vessel. They did not have any money and instead offered to settle the balance with coins of gold. By law, the Technospamech was obligated to report to the authorities what they have recovered. Some plates, a couple of silver coins and some bottles were mentioned and the Technospamech also reported that they didn’t find any gold on the Glen Logan.

Nobody ever seemed to question why they apparently recovered so little after seeing them working intensely for a month just 2,9 miles off the coast with an excavator bucket going constantly up and down.

Back in Great Yarmouth, the two Pearsons, father and son, boast about their fortunate adventure to the local daily paper. They explain that while they were searching for the Glen Logan (which is in fact located hundreds of miles further south of Polluce) when they came across another ship that turned out to be holding quite a treasure when they looked it over with a ROV.

Consequently, they stopped, recovered the treasure and returned home rich - end of the story, at least according to the divers. And at first, their stories were to be believed at face value.

Incredulous

But there is someone else out there who knows that this cannot be the full truth and informs the Receiver of Wreck in Southampton that this treasure must have been removed illegally. The Receiver of Wreck doesn’t quite know what to make of the matter and passes on the information to the Italian embassy in London, which in turn informs the Italian foreign ministry in Rome.

Ultimately it ends up on the desk of the police commander of the Protection Patrimony in Florence who takes interest in the case and initiates an investigation into the case. Appropriating archaeological artefacts in Italy and exporting them illegally is a very serious matter and one that usually comes with a jail sentence.

The police in Florence contacts the London police. The auction house Noonan Webb is then asked to produce documents authenticated by the Receiver of Wreck. Nicholas Pearson and associates do not have them. In the UK the law states that when something is found at sea it must be reported to the Receiver of Wreck. This is the authority dealing with all reports of the wreck from around the UK. It is based within the Maritime and Coastguard Agency headquarters in Southampton, with assistance from Coastguard personnel around the coast.

Pearson protests – and with some reason - that the recovery hadn’t taken place in UK waters and within the Receiver of Wreck’s jurisdiction but in international waters. However, that doesn’t stop the Metropolitan police from arresting the group.

During the following interviews, the divers claim that the vessel they had found was a ship they first called Sea Lion, then changes their explanation calling it the Nostralino - a wreck that possibly is fictitious.

Curiously Nostralino was also the name of the brand of wine aboard. Conceding defeat

But rather than facing years of legal wrangle and even possible imprisonment, they decide to return the booty to Italy and to pay a fine of £2,500 for not having properly declared the finds to the Receiver of Wreck.

And that could have been the end of it. If only if we haven’t uncovered that not all of the treasure was given back.

Who backed it?

However the British authorities refused to reopen the case and when we asked the auction house, Noonan Webb of London, for a copy of their catalogue they refused to state that this was now a police matter. In this auction catalogue was the full but untrue story as the divers had told the police along with pictures of the treasure.

Also, there were pictures and names of all those who had participated in shipping the treasure out of Italy. We then went to visit EDP24, the local newspaper in Norwich where we managed to find pictures of the group along with some others.

Also, we corresponded with the daily paper of Great Yarmouth who related to us that it was probably a local who had financed the operation a person of such influence that the reporters could not speak openly about it. Collecting information in England was not easy. Not only did we meet with a lot of reluctance but we were also being deliberately put on false leads to wrong addresses and telephone numbers that didn’t exist. But that is all part of the game.

The Breakthrough

Then, in December 2004, the ship’s bell from Polluce is found in Paris. In a joint operation between the Italian and French police parts of the treasure that are still missing are traced to a house owned by the very same Pascal Kainic who sold the English divers the historical documents about Polluce in the first place. Searching the premises the police also find other documents and inventory lists implicating both English and Italian citizens who will later have to stand trial. Their offences carries significant punishments but had they at least cooperated and returned the artefacts willingly they would most likely have gotten away with just a fine. But they refused and now have to face the consequences. The trials are set to take place next year.

October 2005

As this magazine goes to press around October 1 another excavation of the Polluce is going to take place. This time a legal one conducted by the Italian off-shore company Marine Consulting Diving Contractor n Ravenna on behalf of The Historical Diving Society of Italy from ito salvage what is left from those modern pirates. The excavation will take place in Archaeological Authority to which has offered their consultancy for free. The operation will cost € 500,000. ■

( Story continues in the next part of the story "Polluce Wreck - the Recovery" )

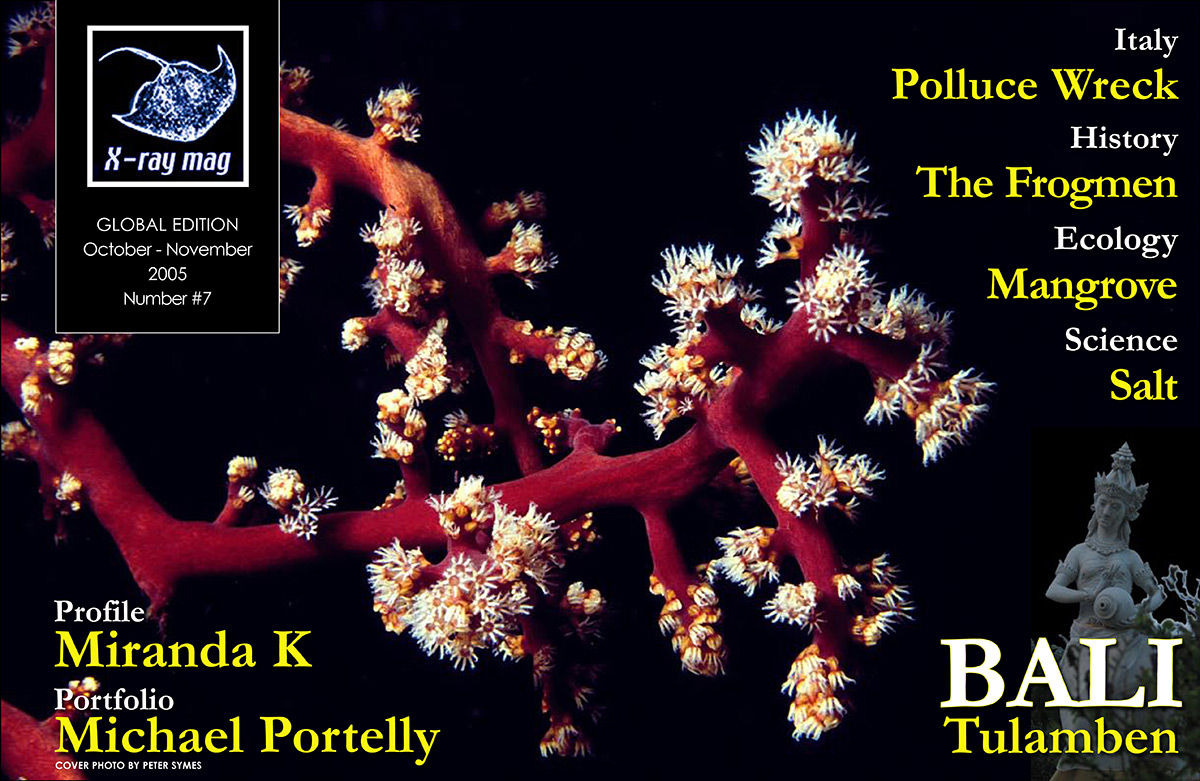

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #7

- Read more about X-Ray Mag #7

- Log in to post comments