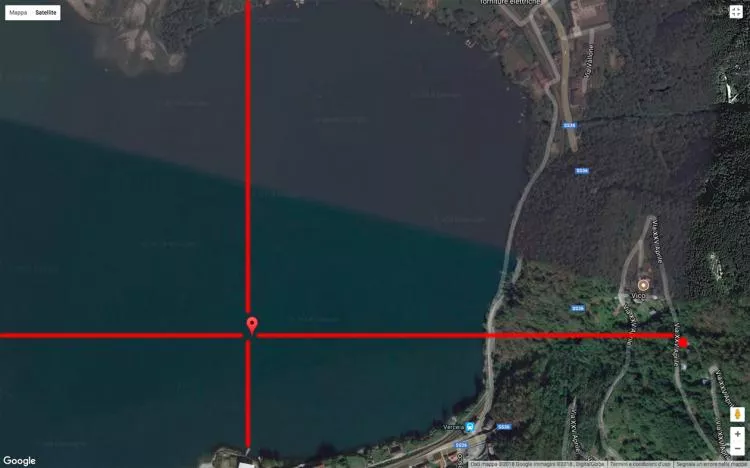

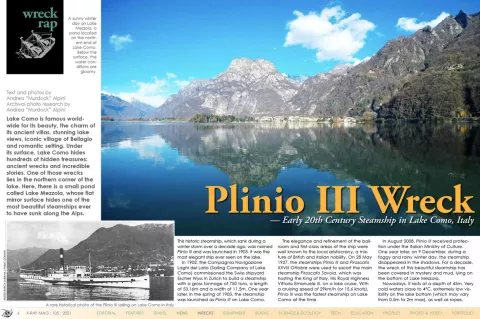

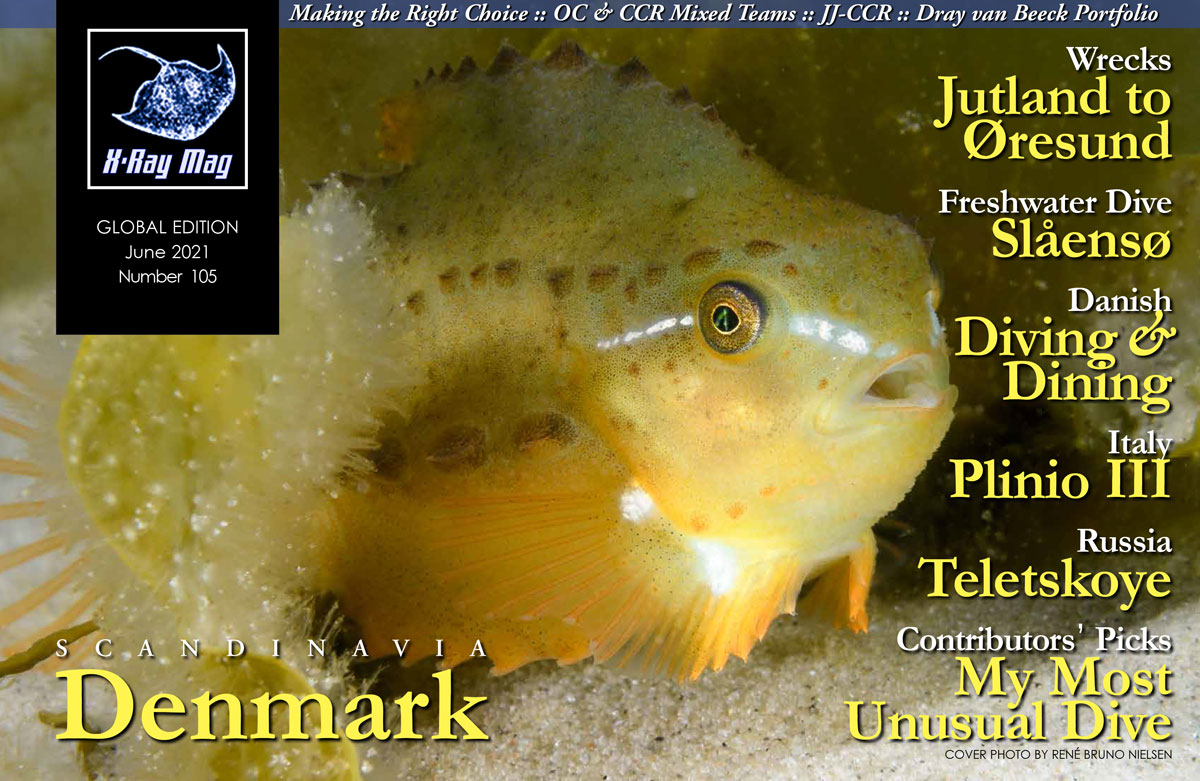

Lake Como is famous worldwide for its beauty, the charm of its ancient villas, stunning lake views, iconic village of Bellagio and romantic setting. Under its surface, Lake Como hides hundreds of hidden treasures: ancient wrecks and incredible stories. One of those wrecks lies in the northern corner of the lake. Here, there is a small pond called Lake Mezzola, whose flat mirror surface hides one of the most beautiful steamships ever to have sunk along the Alps.

Contributed by

This historic steamship, which sank during a winter storm over a decade ago, was named Plinio III and was launched in 1903. It was the most elegant ship ever seen on the lake.

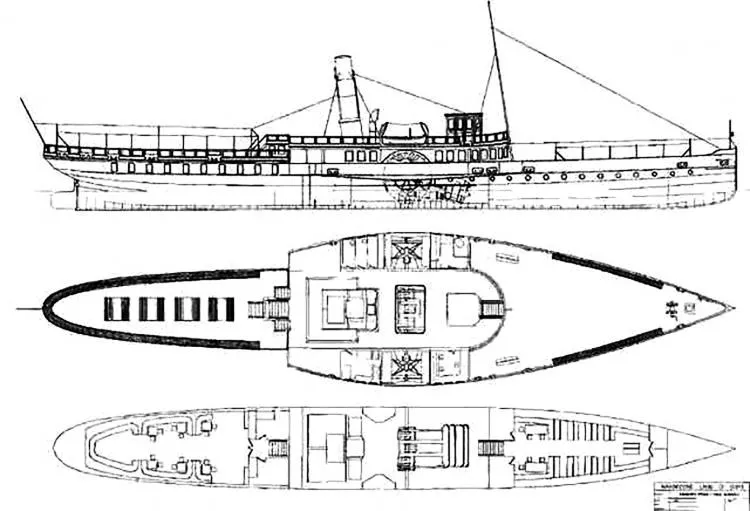

In 1902, the Compagnia Navigazione Laghi del Lario (Sailing Company of Lake Como) commissioned the Swiss shipyard Escher Wyss in Zurich to build a steamship with a gross tonnage of 750 tons, a length of 53.16m and a width of 11.5m. One year later, in the spring of 1903, the steamship was launched as Plinio III on Lake Como.

The elegance and refinement of the ballroom and first-class areas of the ship were well known to the local aristocracy, a mixture of British and Italian nobility. On 28 May 1927, the steamships Plinio III and Piroscafo XXVIII Ottobre were used to escort the main steamship Piroscafo Savoia, which was hosting the King of Italy, His Royal Highness Vittorio Emanuele III, on a lake cruise. With a cruising speed of 29km/h (or 15.6 knots), Plinio III was the fastest steamship on Lake Como at the time.

In August 2008, Plinio III received protection under the Italian Ministry of Culture. One year later, on 9 December, during a foggy and rainy winter day, the steamship disappeared in the shadows. For a decade, the wreck of this beautiful steamship has been covered in mystery and mud, lying on the bottom of Lake Mezzola.

Nowadays, it rests at a depth of 45m. Very cold waters close to 4°C, extremely low visibility on the lake bottom (which may vary from 0.5m to 2m max), as well as ropes, cables and a large quantity of mud, make this wreck dive very risky but also beautiful.

Finding the wreck

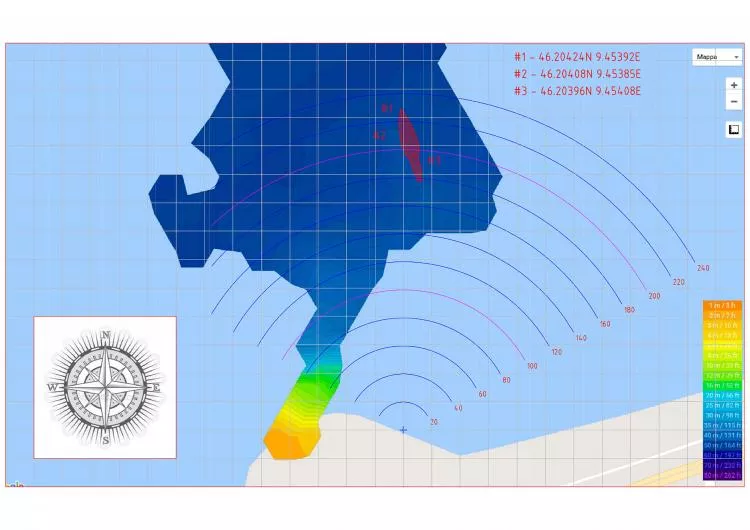

There is no shot line from the surface, nor from the shore to the wreck, so the first job is finding it! Trust me, searching for the Plinio III is not an easy task—it is more an act of faith.

The wreck is hidden under the mud, somewhere in the middle of Lake Mezzola; you cannot see it, but you can sense it is there. One must believe it exists. So, to find the wreck and prepare to dive on it, I spent two years researching its history, location, ship plans and archival photos.

I visited the lake several times to find the wreck, with no success, until one day, with a couple of my friends, Fabrizio Pinna and Renato Oliva, we found it. We were not the first ones to dive the wreck, but a massive flood had mixed up the cards, so-to-speak, so we were playing a different game. The river emptying into the lake, with its mud and stones, had permanently changed the situation of the wreck at the lake bottom.

Diving the wreck

On the day of our first dive, we lowered a magnet, attached to a guideline, down to the wreck. It was wintertime, and the weather had turned cold, with air temperatures dropping below zero. It was sleeting and, on top of that, the wind was blowing and freezing our faces. We were cold, and the search from the surface was taking longer than expected; we spent around two hours in the water. Finally, our grappling hook found the top of the wreck.

After double-checking GPS coordinates, we decided to prepare a downline for diving. When everything was ready, Fabrizio and I started descending along the shot line until we encountered the starboard side of the Plinio III. Renato decided to stay at the surface in case an emergency rescue was needed. The visibility at the bottom was very poor, but it was the best we had encountered in all the dives we had done on the wreck.

The descent

Our descent to the wreck was very slow. We did not know exactly where we were going. We supposed we were on the starboard side in the middle of the steamship, but we were not sure. While descending, we could not even see our hands. And our fins? “Did we even have legs?” I thought, laughing to myself.

My buddy and I kept very close to one another, with Fabrizio staying right beside my arm. The water was so dark, and at the same time, so milky that it was impossible to see our dive lights. Three minutes later, we approached the wreck. We could not see it, so we ended up bumping right into it.

“It’s real!” I thought. “All the words I had whispered in my head about the legendary Plinio III were true!” I kept an eye on our bottom time and fixed the depth and time in my mind. We moved ahead to the bow. We were indeed on the starboard side of the wreck, close to the bridge, as I had suspected when I was still at the surface.

The exploration began. We could only clearly see around 70cm ahead, before things began to get hazy. The study of archival photos and drawings I had done now helped in recognising the parts of the wreck I was touching and could not see. The feeling I had as I was diving—rather, touching—the “glorious” Plinio III wreck, was the sense that it was a fine symbol of a gilded age.

Starboard side

We moved slowly along the starboard side of the deck, moving our fins in slow motion so as not to stir up the silt lying on the wreck. We encountered a bollard and, a few metres farther, a hawsehole, with its steel chain. The anchor was hidden somewhere in the dark muddy bottom of Lake Mezzola.

At the end of our moon walk, we met the razor edge of the bow. “Wow!” I was breathless. It was a pure design belonging to nineteenth-century naval architecture. Awesome. We took our hands off of the wreck just for a minute, as we swam backwards a few metres in order to admire this piece of art, sunken in the gloomy lake.

Port side

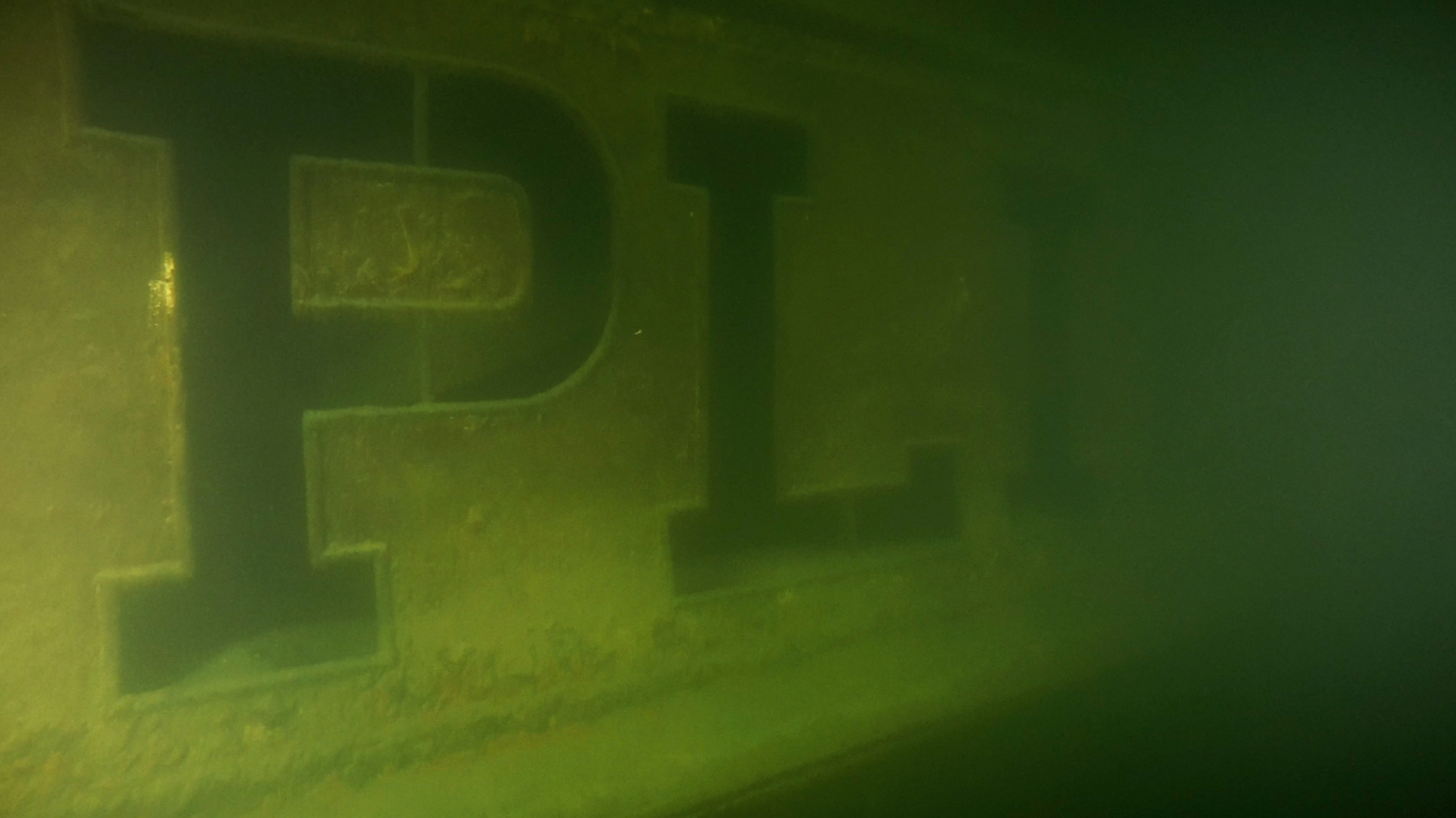

We moved ahead to the opposite side, the port side. When we reached the centre of the steamship, we found the name “PLINIO” on its side. It was not painted; the sign was engraved in metal. Marvelous. Being in front of it, looking at the ship’s name, gave me a great, positive feeling, in spite of the darkness that surrounded us. Fabrizio and I exchanged glances, and we decided to move a bit deeper. We knew that, below the sign, we would find the first of the two steam paddlewheels that comprised the core of the engine propulsion system of the ship.

The stern

A series of portholes ran to our left. The stern was partially collapsed, especially the blue tented awning above it. This part of the wreck was very fragmented and precarious. On the blue awning, a soft layer of 70 to 100cm of mud was just waiting to fall down. We had to move slowly. The wreck was damaged, and some spikes arose from the deck. The Plinio III appeared not be very friendly to its visitors here.

We rounded the stern and were once again on the starboard side of this glorious steamship. Twenty-five metres, more or less, were left in the distance to our starting point. We moved forward slowly. Across the main deck, in the middle of the ship, there was the entrance to the ballroom. Getting inside would be a dream, but it could quickly turn into a nightmare for us. Bad visibility here was an obstacle; we had to make our choices carefully.

Command deck

Again, we decided to decline the invitation and moved on. For the second time, we reached the paddlewheel blades and the ship’s name “PLINIO” engraved on the starboard side of the hull. Five minutes of bottom time remained. We had already spent 25 minutes on the wreck; five more, and our time would be up. Fabrizio and I decided to visit the command deck on the upper level. Here, the same ropes and cables surrounded the bridge and the funnel. We pointed our dive lights into a window. Eternal nothingness. It was too dark to see anything inside.

When our bottom time struck the thirtieth minute, we quickly switched our focus to our decompression procedure. Once we were back at the surface, still breathing from our regulators, we shouted with joy. Today, we had reached the wreck, and we enjoyed the great adventure together as a team.

Afterthoughts

Diving the Plinio III is an act of faith, an incredible place of mind, where one’s emotions and the blood running in one’s veins merge into an illusionistic moment. The experience is unreal! ■

The team’s sponsors include PHY Diving Equipment, Scubatec, Tecnodive Booster, Big Blue Lights, TEMC Gas Analyzers, and Museo Barca Lariana.

Based in Italy, author Andrea “Murdock” Alpini is a technical diving instructor for TDI, CMAS and ADIP. Diving since 1997, he is a professional diver focused on advanced trimix deep diving, log dives with open circuit, decompression studies, and research on wrecks, mines and caves. Diving uncommon spots and arranging dive expeditions, he shoots footage of wrecks and writes presentations for conferences and articles for dive publications and websites such as ScubaPortal, Relitti in Liguria, Nautica Report, ScubaZone, Ocean4Future, InDepth and X-Ray Mag. He is also a member of the Historical Diving Society Italy (HDSI), and holds a master’s degree in architecture and an MBA in economics of arts. He is the founder of PHY Diving Equipment (phidiving.com), which specialises in undergarments for diving, as well as drysuits, hoods and tools for cave and wreck diving. Among other wrecks, he has dived the Scapa Flow wrecks heritage, Malin Head’s wrecks and the HMHS Britannic (-118m), Fw58C (-110m), SS Nina (-115m), Motonave Viminale (-108m), SS Marsala (-105m), UJ-2208 (-108m) and the submarine U-455 (-119m)—always on an open circuit system. His first book (in Italian), Deep Blue, about scuba diving exploration was released in January 2020 (see amazon.it). For more information on courses, expeditions and dived wrecks, please visit: wreckdiving.it.