The island of Jeju, Korea, is an island of myths, gods and goddesses. It is also the birthplace of the women divers of Jeju. Although the women divers of Jeju are not the goddesses of myths, they are real-life mermaid goddesses.

Contributed by

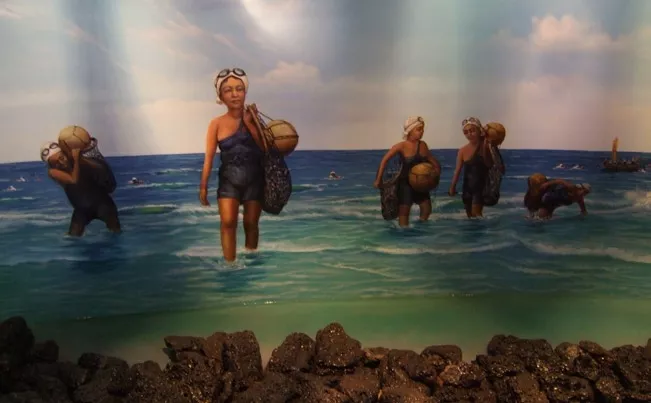

The name for these women divers, in Korean, is haenyeo. It literally means ‘women of the sea’. Traditionally, the women wore only a simple home-sewn white linen combination of pants and a top with lead-weighted vests where they tucked the specialized tools of their trade.

Precise rituals ensure the women’s survival as they free dive in all kinds of weather searching for shellfish and special seaweeds. The divers stay submerged for two to three minutes at depths of 10 to 30 meters with only a float, or taewak, to mark their position. A bag, or mangsiri, that attaches to the float holds the day’s catch. Although the diving tradition continues today, the women now take advantage of modern wetsuits, fins and goggles.

When the divers surface, they make a unique shrill, high-pitched whistling sound that is their way of expelling carbon dioxide from their lungs and breathing in the fresh air.

The women divers usually work in groups. During breaks and at the end of the day, they retire to their bulteok. Although the word means ‘bonfire’ in Korean, a bulteok serves as much more than that. It is a term that signifies an open-air dressing room. It also serves as a place where the women meet to exchange information, opinions and foster the diving profession.

Diving is still an excellent source of income, and as a consequence, the women divers enjoy more freedom, independence and self-respect than other Korean women.

There is a special ranking among the women divers. Group A are the ablest divers. Groups B and C are divided based on experience, character and capability. The groups determine who dives from shore, from boats (to 15 meters) and those who specialize in deep diving (more than 20 meters).

As the women gather around the bonfire, their seating position in the bulteok reflects their position within their group. When a diver is upgraded, her seating position is changed.

Although the working environment of the women divers has not changed appreciably over time, the bulteok has changed. Along with improved diving gear, they have updated their dressing rooms to permanent structures with modern heating. However, the hierarchy of the bulteok is still in practice.

When a diver loses her life, the women stop diving for a while. If they find the body, they have a funeral, but if they fail to find the body, a shaman is invited to soothe the soul of the body and send it to heaven. The shaman also performs an exorcism to prevent evil spirits from causing further disasters.

Expanding business

In their determination to support their families the women divers began diving outside Jeju, according to Japanese history, it may have been before the 5th century. In many cases, the women were fearful of a new experience in foreign lands, but they packed up their diving tools and set off with determination.

According to the 1937 issue of the Jeju Handbook, the business for brown seaweed increased in the late 19th century first in the Busan area, then gradually extended to other cities and countries. The women were often exploited, but because the salary was good they had little choice; they needed the money for their families.

The Jeju women divers began diving, in earnest, in Japan in the early half of the 19th century. Approximately, 1500 women divers went to Japan every year. Instead of using the traditional taewak, they used a dampu, which is similar to a drum with a small net pocket, or they used a board. The Japanese often referred to the divers as itaama or ‘board women.’

In Xingdao, China, after being introduced to brown seaweed by a Korean businessman, there was a need for women divers. In China, the women were called ‘dragon women’ (dragons were a symbol of water and rain and were said to live below the earth). The women worked from May to August making good money.

A number of women went to the frigid waters of Russia to harvest kelp that was too large to harvest from the surface. Because whales often shook the ships they were working on, they were asked by the person in charge to dive silently.

During the Japanese occupation of Korea from 1910 to 1945, the women divers of Jeju rose up against atrocities of the Japanese to fight for their rights. They led anti-Japanese campaigns that allowed them to boycott Japanese-run businesses and establish cooperatives to preserve marine resources after the Japanese governor ran up the price of shellfish.

Girls over boys

Most Koreans aspire to have baby boys, but on Jeju it is different; the birth of a baby girl is valued. There is an old saying in Jeju, “When you have a baby girl, butcher a pig and have a party. If it is a boy, just kick him in the butt.” The saying accurately reflects the importance of women as the backbone of the Jeju family.

Island girls start diving by the age of 10 or 15. At that time, they are ready to earn a living.

A decline in mermaids

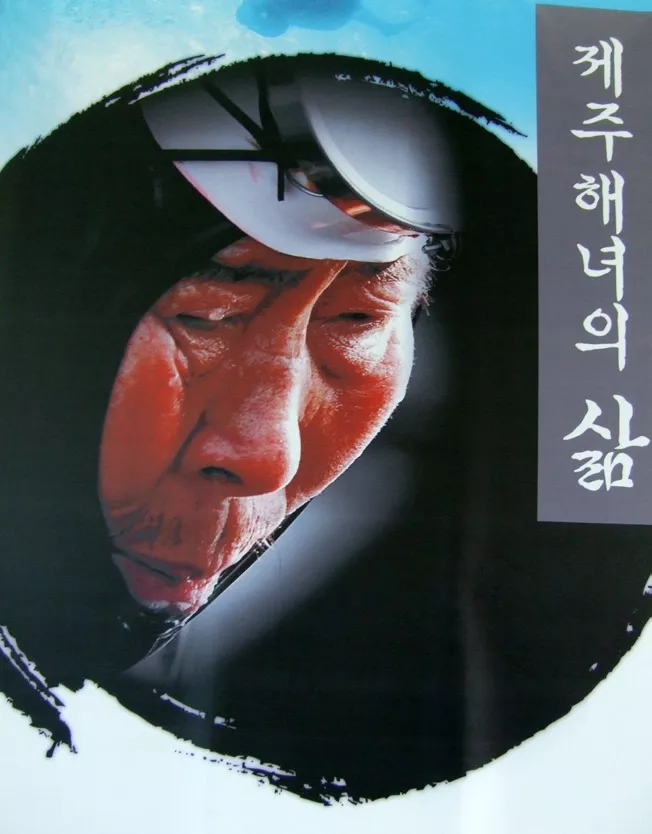

The number of women divers has decreased dramatically in recent years. More job opportunities, education and mothers do not want their daughters to follow in their strenuous and dangerous profession. In 2006, there were only 5,406 women divers, and those over 60 years old accounted for 65.8 percent (3,557); those between 50 and 59 just over 24.6 percent (1,331); those between 30 and 49 only 9.6 percent (518); and those below age 30 number only two. In contrast, in 1970, the number of women divers over the age of 60 was only 4.6 percent.

Due to the rapid decline in the number of women divers and their aging population, the Haenyeo Museum was established in Jeju to honor the mermaids. The museum is located in the village of Hado-ri where many haenjeos have traditionally lived. The museum has many exhibits showing the haenjeo’s way of life, working tools, diving dress and models of their homes.

William Logan the UNESCO Chair of Heritage and Urbanism said Jeju women divers represent a unique legacy that deserves a nomination for the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Logan said, “The point of the intangible cultural heritage is to draw the attention of the international community to the threats to this particular heritage around the world and support Korea in finding ways to maintain these skills from donors and educators.”

Today, most of the women divers are over the age of 60, some are widowed, and some are still the sole economic source for their families. The haenyeo divers continue to survive through their wits and the strength of their communities. They are incredibly strong and remain healthy, fit and beautiful.

Dutch sailor Hendrick Hammel, a survivor of the 1653 shipwreck on Jeju, recorded in his logbook that “real mermaids” existed on Jeju. ■

Bonnie McKenna is an internationally known fine art photographer specializing in the beauty of life under the sea and the nature of the great outdoors. She is a PADI certified Master Scuba Diver Trainer. She has written for several publications including D-Log—an interactive dive log for the islands of Palau—Houston Community Newspapers and The Tribune News-papers as a travel writer after a long career with Continental Airlines. She is currently a reporter for the Houston Chronicle.