As a divemaster in Japan, I have enjoyed diving all around the world, and I will admit that there are many places on earth I would love to revisit soon. But for today, I would like to introduce my home country, Japan, as your next possible dive destination.

Contributed by

Before the pandemic, Japan put great effort into inviting tourists from around the world to visit our country. Inbound tourism was treated as a growing industry, which is now an extremely important part of the Japanese economy.

Presently, many resources and a lot of money are being poured into “Visit Japan” promotions all around the world by Japan National Tourism Organization (JNTO), and as a result, tourist sites all around Japan have become packed with international travellers.

But this has not been the case for the dive industry in Japan. Happy and content with business from local Japanese divers, the dive industry was not interested in expanding its market to international divers. As an avid diver in Japan, this was a good thing. While the whole of Japan faced issues of over-tourism, the dive sites all around Japan were not affected.

But as a country with its diving population growing older and smaller, I asked myself, “Is this a good thing?” My answer was very simple, “I believe not.” I think Japan should get the recognition it deserves as a top, world-class dive destination, and welcome more divers from around the world—and if I can help, I will do my best to share what I know and love about diving in Japan.

Today, l would like to introduce Osezaki to you. Located in Numazu, Shizuoka Prefecture, it is a popular destination for local divers in both the Tokyo and Nagoya regions. As a resident divemaster of Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, it is my home base—a weekend dive destination, where I log more than 200 tank dives per year. But before I explain how great Osezaki is, let me explain why diving in Japan is so special and unique to begin with.

Japan, as a tourist destination, was booming up until the pandemic. I believe Japan still has the potential to recover as a travel destination as soon as travellers around the world feel safe enough to travel again and visit our country. You never need to wonder what you can do besides diving, as your “aprés-dive” activities and experiences probably will not be an issue. You can enjoy our unique traditions, culture and delicacies.

Diving in Japan

Now, for diving in Japan. Japan has four unique features that I believe are important to mention. Firstly, Japan has four distinct seasons both on land and underwater, and within the same season, you can do cold-water to tropical-water diving, depending on your diving preferences—all within a two- to three-hour domestic-flight range.

When you choose your dive destination, you do not have to choose a country according to your diving preferences, you only need to choose Japan. You can dive nutrient-filled kelp forests and see giant octopus at Hokkaido, which is a cold-water dive location; or you can dive with large schools of sharks, such as Japanese hound shark and hammerhead sharks near Tokyo, which is a subtropical dive location; or you can choose a tropical beach resort in Okinawa and dive with manta rays. You can probably find almost every type of marine creature in Japan.

Secondly, Japan has 6,852 islands, and our coastline is 33,889km long (which is about 85 percent of Earth’s diameter), with many parts forming a jagged saw-shaped coastline, which is ideal for marine life to flourish. Due to this very reason, the fishing industry in Japan is old but small, mostly occurring off the coastline, thus continuing to protect the environment for marine life near our shores.

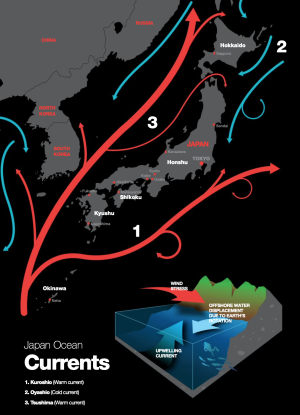

Thirdly, Japan is fortunate in that both warm currents from the south and cold currents from the north mix off its coasts. The strength of currents changes with the seasons, thus dramatically changing the underwater scenery and the marine life one can see at the same dive site. This is especially true for dive areas near Tokyo. Here, you get to see both cold-water and warm-water creatures thriving in the same area. If you are lucky, you may see tropical marine life carried up on the currents from the south as well.

Lastly, Japan is surrounded by deep-water trenches reaching down to more than 2,000m in depth, just a few kilometres off the coast. The winds and Earth’s rotation cause the upwelling current, rich in nutrients from the deep, to bring with it rare deep-water creatures up to recreational diving depths.

You need to be selective in choosing the right dive location to really see the deep-water creatures, but if you do, and you get the timing right, you may be in for a big surprise.

With all these factors combined, Japan hosts 14.6 percent of the 230,000 marine species that can be found around the world—a dream dive destination for any avid diver for sure.

Osezaki

Now, let’s talk about Osezaki—my home diving spot. Osezaki is a dive location situated on the western shore of the Izu peninsula, facing the 2,000m deep Sagami Bay. A two- to three-hour drive from downtown Tokyo, it is a popular dive destination for many divers in Tokyo and Nagoya.

So, why is Osezaki so popular?

Personally, I like the magnificent view of Mt Fuji, which you can see from the dive sites. I also like the fact that Osezaki is one of the oldest dive locations in Japan, has well-established dive site rules, and one can easily buddy dive without a guide there. Of course, you need to show the dive centre that you are not a “blank” diver and have extensive buddy-diving experience. Even if you are not used to buddy diving, you can ask for guide service at one of the many dive shops situated in the area.

I also love Osezaki for the diversity of marine life that one can encounter here, making this site very popular among divers with a passion for underwater photography and observing marine life behaviours.

Dive sites

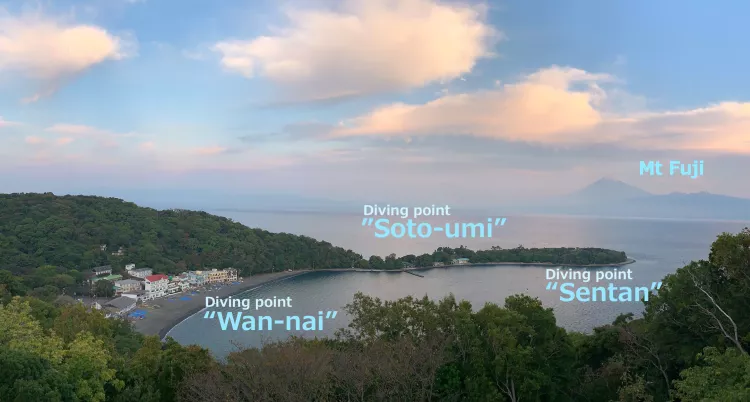

Osezaki has three distinctive beach entry points, offering divers different types of underwater terrain and endemic marine life.

Wan-nai. Wan-nai translates to “inside bay.” This location sits in front of the many dive centers located in Osezaki. The bay is well protected from wind and waves, and is rarely closed for weather-related reasons. Even when all the other dive sites in the area may be closed due to a hurricane, and if the hurricane does not directly hit Osezaki, there is a big chance that Wan-nai will remain open.

In the summertime, the average visibility is around five to eight meters inside the bay. In the wintertime, the visibility may improve up to 20m.

The entry point is a 20 to 30m walk down the black sandy beach, which stretches across the bay. After entry, you need to swim 20 to 30m across a shallow, rocky, two-meter area before dropping down to the sandy floor at 8m. Depending on the direction you head out from here, the sea floor changes from sand to mud, with many man-made underwater sanctuaries providing a home to a variety of marine life.

If you want to look for gobies, this is the site to dive. The idol of the bay is the tiny photogenic yellow pygmy goby (Lubricogobius exiguus). A pair of rare monster shrimpgoby (Tomiyamichthys oni sp.) have been residents here for a year now. They are very shy, but you may be lucky to see them together.

Among the common gobies, one can find the blue hana goby (Ptereleotris hanae), yellownose prawn-goby (Stonogobiops xanthorhinica) and filament-finned prawn-goby (Stonogobiops nematodes), which are popular species. Last but not least, is the very rare blue-tailed shrimpgoby (Cryptocentrus pavonioides). This is a seasonal species found only during a short period between summer and autumn. Its beautiful colour attracts many underwater photographers from all over Japan.

The Wan-nai dive site is also the only place where night dives are allowed at Osezaki. Here, you can dive at night on Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday.

From November until March, many local dive shops host “light trap dives,” where one can observe creatures coming up from the deep and in from the open sea. Here, you may get to see many rare creatures, rarely seen elsewhere around the world. If you are lucky, you may see a juvenile oarfish during your dive.

What you can see (all year-round):

- Many types of seasonal nudibranchs

- Many types of shrimp and crab

- Many types of gobies

- Many types of frogfish

- Many types of squid and octopus

If you are lucky:

- Harlequin ghost pipefish (Solenostomus paradoxus) in autumn

- Feeding John Dory (Zeus faber) in winter

- Monkfish (Lophidae) in winter

- Oarfish young (Regalecus) in winter

- Peregrin dealfish (Trachipterus trachypterus)

Soto-umi

Soto-umi translates to “outside ocean.” This location is situated on the other side of the cape of Osezaki, facing the open waters of Sagami Bay. Due to its location, the visibility is often better than at the Wan-nai dive site, and the underwater terrain is more dramatic.

There are three entry points here, all with concrete paving for divers, covering the 200m rocky beachfront. After entry and heading straight out to the open sea, you can dive down to 20 to 30m. The underwater terrain is mainly composed of large rocks and sand.

Depending on the season, you may be lucky enough to see the resident purple goose scorpionfish (Rhinopias frondosa), which shows itself to divers from time to time. Also, there is a large Asian sheepshead wrasse (Semicossyphus reticulatus), which can be seen swimming around the area from time to time. Sunfish (Mola mola) have often been sighted in the past, but not so often recently, maybe due to climate change.

What you can see (all year-round):

- Many types of seasonal nudibranchs

- Many types of shrimp and crab

- Many types of frogfish

- Many types of squid and octopus

If you are lucky:

- Sunfish (Mola mola) in winter

- Goose scorpionfish (Rhinopias frondosa)

- Asian sheepshead wrasse (Semicossyphus reticulatus)

Sentan. Sentan translates into “tip (of the cape).” It is only open to divers on weekends and public holidays. The cape of Osezaki and the Ose Shrine are popular tourist attractions for non-divers as well. The shrine was founded in 684 AD and has long been known to house the guardian deity of the sea. If you are a diver, I do recommend you say hello to the local deity of the sea.

To reach the dive entry point, you need to pay a fee of 100 yen (per person) at the entry gate, so please do not forget to bring coins with you. The entry point is at a 15m rocky slope, descending to the ocean. After entry, there is a steep slope descending to 50 to 60m, so it is very important to control your descent. You also need to check the tides as sometimes the currents may be challenging.

The location is famous for the variety of anthias you can see on one dive. Common anthias found here include the sea goldie (Pseudanthias squamipinnis), red-belted anthias (Pseudanthias rubrizonatus) and cherry anthias (Sacura margaritacea). If you dive deeper, you may be able to see nagahanadai (Pseudanthias elongatus), sea goldie fish (Pseudanthias sp.) and one-stripe anthias (Pseudanthias fasciatus).

What you can see (all year-round):

- Many types of seasonal nudibranchs

- Many types of shrimp and crab

- Many types of tropical water creatures

- Many types of anthias

If you are lucky:

- John Dory (Zeus faber) in winter

- Sea goldie fish (Pseudanthias sp.) in deeper waters

- Bicolor anthias (Pseudanthias bicolor)

- Pink basslet (Pseudanthias hypselosoma)

I hope you are now interested in considering diving in Japan, and especially Osezaki, in the future. If you want more information about diving in Japan, please visit my site, DIVE IN JAPAN, at: dive-in-japan.com.