Komodo Island kept bobbing in and out of my field of vision as we continued to circle in water that was churning. I could almost see the Pacific colliding with the Indian Ocean. Ali, one of the many talented dive guides from the luxury liveaboard Arenui, popped up from the depths and shouted, “The current is going off!”

Contributed by

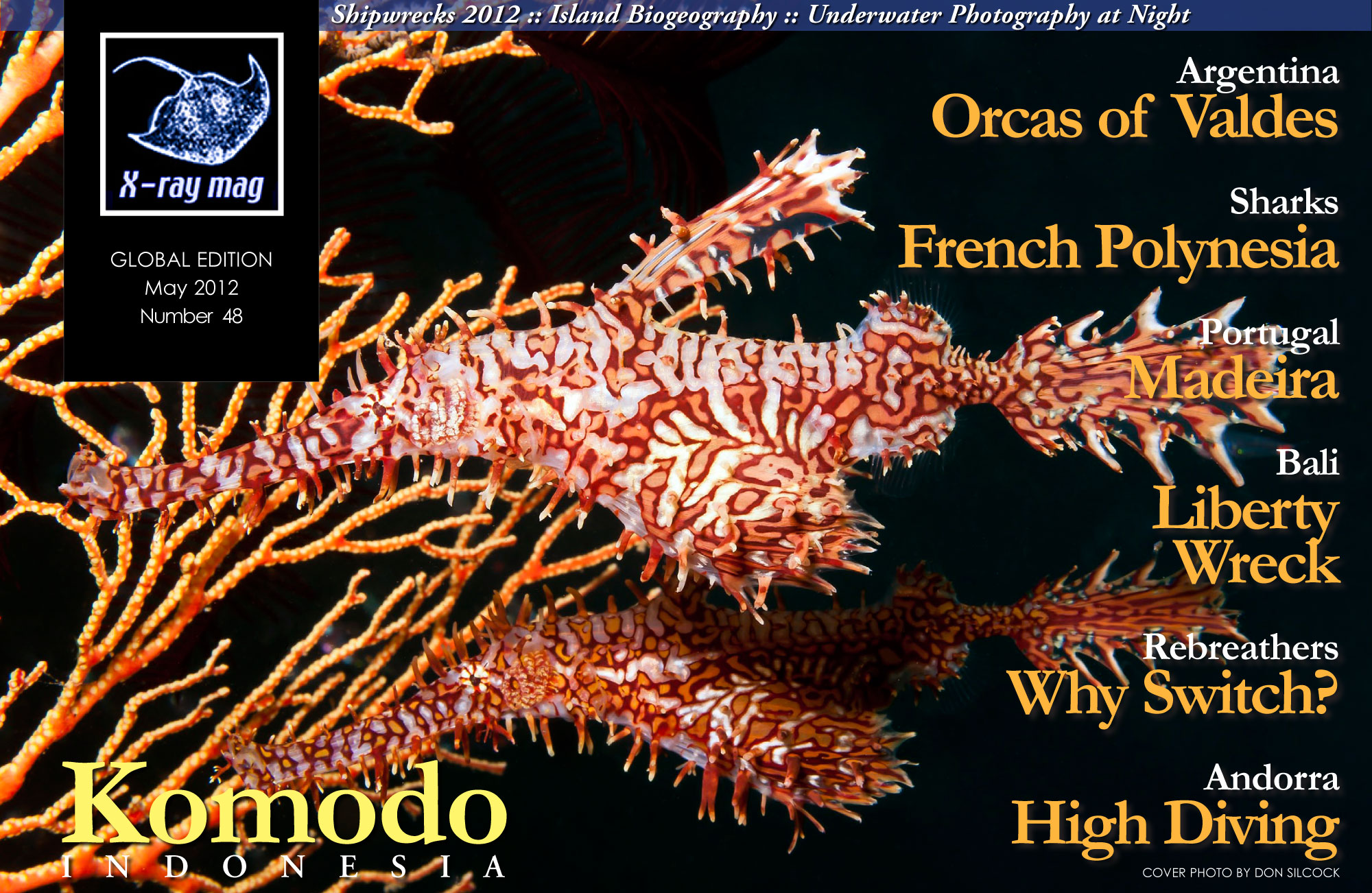

We were here because when two oceans meet, there is magic to behold. The cool, nutrient rich waters of the Pacific combine with the warm shallow waters of the Indian Ocean are the perfect recipe for thriving life and diversity. Add into the mix a living volcano and deadly oversized lizards and you have yourself Komodo National Park.

The area of Komodo is comprised of three large islands, Komodo, Rinca and Padar as well as 26 more, and was originally protected in 1980 for the dragons themselves. However, later exploratory diving, largely by Larry Smith, revealed the wonders below the land of the lizards. Hence, the park, in its entirety, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1991.

Diving

Skirting the edge of the seamount, we swam into a flatter patch of the dive site known as Crystal Rock and had a reprieve from the impressive current. Here, brightly colored soft corals bloomed around us, and the fusiliers and trevally continued their tango of cat and mouse above our heads.

When the sun suddenly became blocked, all our heads snapped skyward to witness the fusiliers compacting tightly into a seemingly endless school, as the trevally made their move. It was impressive, and I sensed that we were not the only ones on the reef observing the action.

Continuing on, we again fought the current and connected our reef hooks to the cusp of the reef. Below us, we beheld the show of white-tip sharks and the occasional grey reef shark while our regulators ceaselessly vibrated against our mouths.

Both Crystal Rock and Castle Rock are dive sites where one coud feel the power of Komodo’s unpredictable and infamous currents. But to really experience the bounty these nutrients’ yield, we had to travel south, and add another layer.

The waters in Horseshoe Bay, at the southern end of Rinca Island, harbor constant and unpredictable upwellings of cold ocean water from the Savu Sea. These currents carry nourishment and spark phytoplankton blooms that on one hand drop the visibility, but on the other produce the most resplendent reefs I have ever laid eyes on.

Tucked in Horseshoe Bay is Cannibal Rock, named for a voracious Komodo dragon observed eating another. To say the reefs are flourishing is an understatement.

Here, life thrived and critters jostled for precious real estate. As we slowly sank down the wall that comprised this dive site, I heard our talented cruise director, Debbie Benton, giggling through her regulator and pointing. On the wall, tucked into some sponges, was the tiniest juvenile warty frogfish I had ever seen. How she spotted it, I will never know.

The icing on the cake was located at the base of the wall in all his pink glory—a paddle flap rhinopia. He shifted to show me his best angle, and I snapped a few photos. The dive just got better as we continued—nudibranchs, sea apples, anemonefish, eels, crabs and more frogfish. I was dazzled by the shades of purple and green, as we made our way up the wall.

In this area, night dives became even more appealing than an early cocktail on the upper deck of our splendid boat. Although they were shallow, 45 feet at most, the black, ...

Published in

- Log in to post comments