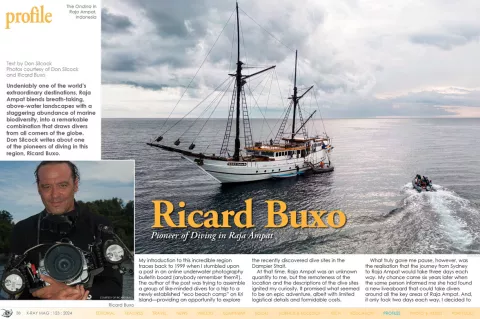

Undeniably one of the world’s extraordinary destinations, Raja Ampat blends breath-taking, above-water landscapes with a staggering abundance of marine biodiversity, into a remarkable combination that draws divers from all corners of the globe. Don Silcock writes about one of the pioneers of diving in this region, Ricard Buxo.

Contributed by

My introduction to this incredible region traces back to 1999 when I stumbled upon a post in an online underwater photography bulletin board (anybody remember them?). The author of the post was trying to assemble a group of like-minded divers for a trip to a newly established “eco beach camp” on Kri Island—providing an opportunity to explore the recently discovered dive sites in the Dampier Strait.

At that time, Raja Ampat was an unknown quantity to me, but the remoteness of the location and the descriptions of the dive sites ignited my curiosity. It promised what seemed to be an epic adventure, albeit with limited logistical details and formidable costs.

What truly gave me pause, however, was the realisation that the journey from Sydney to Raja Ampat would take three days each way. My chance came six years later when the same person informed me she had found a new liveaboard that could take divers around all the key areas of Raja Ampat. And, it only took two days each way. I decided to go… which was how I came to make my first trip on the SMY Ondina and meet Ricard Buxo!

Background

At that moment in time, Ricard had been residing in Indonesia for more than five years, fully immersed in the adventure of a lifetime, and it was unmistakably evident. Back then, my experience with the country was limited to some business trips to the capital of Jakarta, together with a couple of dive trips to Bali and Komodo. But essentially, I was oblivious to the vast expanse of Indonesia’s 16,000+ islands.

In stark contrast, Ricard had a deep understanding of the country, its diverse peoples and their rich cultures, which he graciously shared on that first trip. Moreover, he showed me how to dive in the strong currents that were the lifeblood of the archipelago. I had no way of knowing, but that voyage aboard the Ondina in Raja Ampat was the start of my enduring fascination with the enigmatic wonder that is Indonesia.

Mutual friends

The catalyst for Ricard’s Indonesian adventure was a meeting in Barcelona with fellow Spaniard Enrique Rubio—brokered by a mutual friend who knew what they were both looking for. For Ricard, that was a new and exhilarating chapter after five years of working on liveaboards in the Egyptian Red Sea, while Enrique was on a quest to find the ideal individual to transform his vision for a business in Indonesia into a tangible reality.

Enrique had been a regular visitor to Indonesia since 1982, when tourism had just begun to establish a foothold in Bali and yet remained largely absent throughout the rest of the archipelago. But it was not surfing and sandy beaches that brought him here all the way from Spain, rather, it was the highlands of what was then referred to as Irian Jaya, the Indonesian western half of the huge island of New Guinea.

The highlands are formed by the Central Cordillera Mountain ranges, which stretch east to west across the vast expanse of New Guinea, the second largest island in the world. Cradled within those rugged mountains are a multitude of fertile river valleys which provide sustenance for a mosaic of agriculture-based tribal communities. Remarkably, it was not until the 1930s that these tribes experienced their “first contact” with outsiders.

West Papua

Irian Jaya (now known as West Papua) was, and continues to be, one of the most remote and untamed parts of Indonesia, and Enrique, together with a small group of fellow adventurers, was determined to explore those highlands. They embarked on a month-long trekking expedition through this wilderness, and numerous adventures unfolded as they journeyed from valley to valley, visiting and staying in remote tribal villages. Foremost of these was witnessing the sudden outbreak of an inter-tribal war that left them all stunned and more than a little concerned about what could have happened!

That adventure turned into a series of annual assignments leading trekking expeditions in the highlands, and after a few years, Enrique decided the timing was right to start a tourism-focused business in Indonesia. Initially, the idea was establishing a resort for trekkers in the highlands, but over time the concept of building a boat and using it to take divers around the archipelago was born.

The Bugis

But not just any boat… the idea was to take the proven design of the traditional Indonesian sailing ships and build a customised version that would enable journeys of discovery to some of the remotest corners of the vast archipelago. So, Enrique went to South Sulawesi, home of the Bugis—the accomplished seafarers who roamed the seas long before the first Europeans arrived in what was then known as the Malay Archipelago.

Equally feared and revered, the Bugis are said to have navigated by the stars as far as Madagascar to the west, China to the north, and the top-end of Australia to the south. They carry reputations as adventurers, warriors, slave runners and pirates, and are said to be the source of the English saying, “Watch out, the bogeyman will get you.”

In fact, they were also astute merchants who used their boats and seafaring skills to trade exotica far and wide. The Bugis built their own boats called padewakangs in South Sulawesi, and when the Dutch colonised what we now call Indonesia in the late 1700s, they did so in their European-style sailing ships. Over time, many of the key features of those European schooners were incorporated into the sailing ships built by the Bugis. Eventually, the amalgamated design became known as the pinisi.

Building a pinisi

Enrique found the boat builders he needed in the village of Tanah Beru, near the town of Bira. While negotiating, he realised there was no standard design for a pinisi, with each build a function of individual wants, needs, customs and traditions. All these factors were discussed at length with the team building the boat—usually a family clan of shipwrights and carpenters, typically led by a construction manager who was a haji, a Muslim who had completed his pilgrimage to Mecca and commanded great respect. But even when the final concept was agreed upon, there were no formal plans drawn up or budgetary estimates provided—the boat just evolved around what was discussed!

Finally, a deposit was paid, and the need for someone to supervise it all became rather urgent…

Living with the Bugis

Imagine, if you would, moving to a remote part of what was then a third-world country, to live among local boat-builders in basic conditions to supervise the construction of a traditional wooden boat—all without an agreed final plan or budget, without speaking a word of the local language and with zero knowledge of local customs and traditions. But that was what Ricard did in June 2000, just as the keel of the yet unnamed boat was being laid.

Some 13 months later, the boat was launched and christened Sailing Motor Yacht (SMY) Ondina—the Nymph of the Deep Sea!

Ondina was not the first pinisi built for foreigners, but it was the first to be crafted as a dedicated liveaboard, and Ricard describes those 13 months as the most intense, challenging, but deeply satisfying period of his life, as the boat took shape on the beach at Tanah Beru.

His five years in Egypt had given him the strong foundation he needed for the total “cultural immersion” he went through in living with the Bugis, learning how to communicate with them and ensuring that the pivotal details, which make Ondina such a great diving platform, were implemented.

A mystical process

Indonesia is the largest Muslim country in the world and is known for its secular brand of Islam and religious tolerance. Many of the racial groups that make up its almost 270 million inhabitants combine their version of Islam with historical myths and beliefs, which in many ways makes the country so interesting.

But the Bugis are amongst the most fascinating of those groupings, combining a deeply superstitious nature with animistic traditions, rituals and legends, which are intertwined with how they build their pinisi. Everything has its place, with the overall process guided by the haji, who has complete responsibility for the integrity of the construction and ensuring that all the traditions are followed properly and thoroughly.

From a western perspective, it would be easy to simply dismiss the spiritual element of building a boat as irrational and irrelevant, but consider this from the Bugis point of view. The boats take their people far and wide in the monsoonal seas of the archipelago and even out in the open oceans—sailing at the whim of the elements and finding their way using the stars.

No detailed plans for the pinisi are ever made, or ever will be… There is no manual, the skills and methodology are transmitted orally and taught to younger members of the clan, who in turn pass them on to the next generation.

And then the hard part!

After Ondina was launched, the priority was fitting out the boat in preparation for the customers booked on the first trip. Ricard was kept exceptionally busy supervising the fit-out while also hiring and training the first crew, dealing with the considerable paperwork and working out the routes Ondina would follow around the archipelago—not to mention where to dive!

Then, just 30 days before the first trip was to depart, the devastating 9/11 terrorist attacks occurred in New York, effectively shutting down all air travel globally. If you had to pick a worse date to launch a business in a Muslim country that requires tourists to fly long distances to get on board, October 2001 would probably meet all the selection criteria.

Still, most of those who had booked made it to Indonesia, and Ondina left on that first voyage. So, maybe there is something to those rituals and ceremonies the haji orchestrated as Ondina was built!

Exploring the Indonesian Archipelago—Follow the Bugis!

Indonesia is a vast archipelago of 16,000-plus islands, and in 2001, when scuba diving was in its infancy, there was virtually no public domain information available on where to dive and what the associated hazards might be. The only people to ask were the pioneers who had come before Ricard—Edi Frommenwiler, the late Larry Smith, and Mark Heighes, all of whom generously shared their knowledge. But it was his time with the Bugis that inspired Ricard to follow in their footsteps and sail with the monsoonal winds around the archipelago.

He started with the Lesser Sunda Islands, along the southeastern rim of the archipelago, concentrating on the areas around Komodo and Alor. He did so with those first passengers discovering some of the very best spots—plus, they were the only boat in the area!

Then, after two years diving in the south, in October 2003, Ricard took Ondina north, across the huge expanse of the Banda Sea for the first time—a journey of some 1,000km to Sorong— and joined the small number of boats based in Raja Ampat through to March each year. The area became Ricard’s favourite part of the archipelago. So much so that he was one of the first people to write a book about the area, Underwater Paradise—A Diving Guide to Raja Ampat, which has become the standard for all guides operating in the area because of its excellent maps and descriptions of the sites covered.

A life well lived

Ricard stepped back from Ondina in 2015 and is now based in Bali. With his wife Paulina, he runs its overall operation, alongside that of its sister ship MV Oceanic. I catch up with him regularly to find out what is happening underwater across the archipelago, because the regular updates from both boats, plus his extensive contacts across the liveaboard industry in Indonesia, keep him very well informed!

Every liveaboard trip I have done in Indonesia since 2005 has been on the Ondina—why, you may wonder, when there are now over 100 to choose from? Two basic reasons… first, I have been on board in horrendous weather in the Banda Sea—the sort where you know exactly where your lifejacket is, but we made it through, and I trust the boat.

Secondly, everything about Ondina, from the way the diving is run to the way the meals are prepared and served, just works as it should. Essentially, Ricard may not be on board that often, but the system he established continues to function as he intended it to. For me, it is the perfect, proven platform to experience the many delights of underwater Indonesia! ■