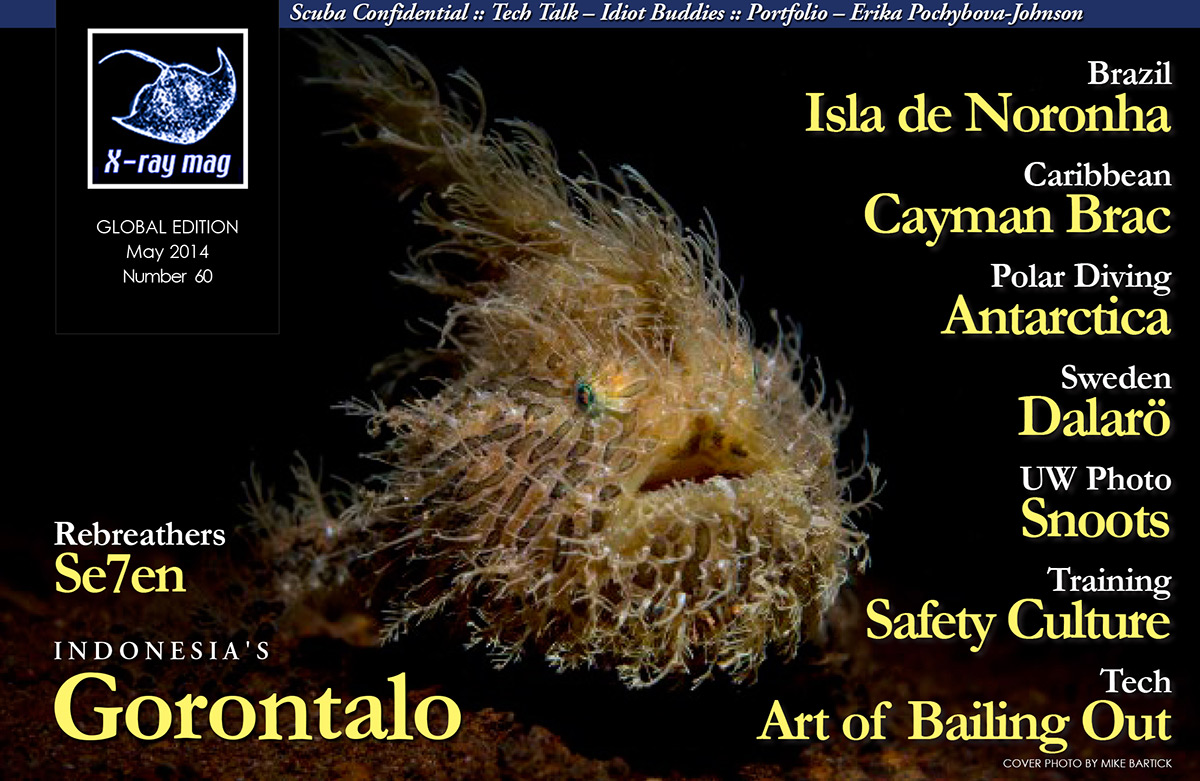

Barely beaten tracks are an increasingly rare find for travellers in this ever more accessible world. Yet on the shores of Tomini Bay on the Indonesian Island of Sulawesi, one such place still exists.

Contributed by

Factfile

References:

[1] Hooper, J. N. A. & Van Soest, R. W. M. (2002) Systema Porifera. Guide to the Supraspecific Classification of Sponges and Spongiomorphs (Porifera). Plenum, New York.

[2] Allen, Rantje. Gorontalo: Hidden Paradise, ISBN: 9789810561291

Gorontalo Province lies on a peninsula extending from the northeast of the flower-shaped island of Sulawesi, reaching out towards the Philippines. This peninsula, known as the Minahasa, is bounded by the Celebes Sea to the north and the Gulf of Tomini to the south, and it is on this southern ocean boundary that the provincial capital, Gorontalo City, lies. The term City, however, is deceptive, since Gorontalo is more akin to a rural town, where chickens risk all as they cross roads that are traversed by over-laden scooters and motorised rickshaws, known locally as bentor.

Along the main streets, double-parked horse-drawn carts contrast sharply with shops that hint at influences of the modern world—the mobile phone accessory outlets that fuel Indonesia’s fascination with mobile communications. This is an obsession that has led the country to become the world’s fourth largest user of cellular phones. Yet, despite these few signs of the emergence of modern day culture, Gorontalo City remains distinctly traditional and a world away from the usual hustle and bustle you expect to find in an Indonesian city.

Legend has it that when the seas subsided, Gorontalo appeared on a plateau amongst three surrounding mountains. Whether the legend is true or not, there is no denying that the landscape here is ruggedly beautiful, comprising steep cliffs and valleys that channel fresh water on a downward journey toward the sea, cutting swathes through the soft limestone on the way. It is at the coastline where the vulnerability of limestone to natural erosion is most strongly evident and the impact on the underwater topography is dramatic.

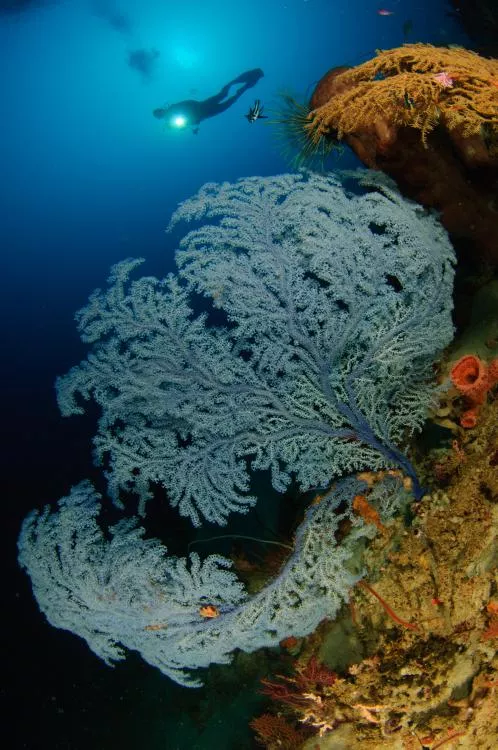

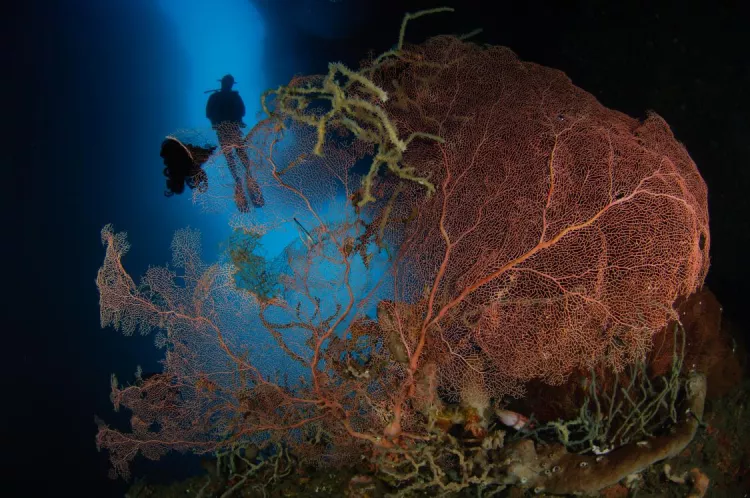

To the east and west of Gorontalo City, steep cliffs plummet vertically into the sea and underwater channels and gulleys lead the way to the extreme depths of the bay. These are often beautifully interlaced with catacombs of chimneys, caverns and tunnels, providing refuge for some of Gorontalo’s numerous species, some of which are endemic.

Tomini Bay is over 4,000 metres deep, and the seabed drops so rapidly that it is common to see open ocean species such as whales, dolphins and strange pelagic invertebrates close to the shoreline. A plummeting seascape so close to land also has other benefits, in providing a near-shore habitat for sessile species that would otherwise be vulnerable to shallow water wave action and therefore in the depths they can thrive.

Giant sponges

Descending past 20 meters, you enter the domain of the giant sponges, firmly gripping the porous limestone while the nutrient-rich currents wash over them. Simple multi-cellular animals rather than plants, there are around 8,000 described species of sponge, with the total number of species thought to be upward of 15,000 [1], classified collectively under the scientific phylum Porifera, which means “pore bearing”.

Filter feeders, they also lack any distinct digestive system and rely on their collar cells to force water through their structures, bringing in nutrients and oxygen and taking away carbon dioxide. Here in Gorontalo’s depths, they are able to grow to enormous sizes.

Amongst Gorontalo’s healthy sponge population, a phenomenon has occurred that illustrates perfectly how local conditions can influence evolution. The sponge in question is Petrosia lignosa, a species found only in Sulawesi and the Philippines and first described by renowned zoologist Henry Van Peters Wilson in 1925.

In Gorontalo waters it grows with an intricate, deep swirling pattern etched on its surface, which so far has only been observed here. Local dive pioneer Rantje Allen was the first man to document this unusual morphology and has christened the species with a name befitting the bizarre patterns—“Salvador Dali”—named of course after the surrealist Spanish painter.

These sponges come in various shapes and sizes, the largest can be over three metres in length. All of them display the distinctive patterns, from juveniles of only 20cm in length to those that have reached gargantuan sizes. The Salvador Dali’s have been observed in two colours, a dark shade of brown, sometimes with a green tint, or light grey for the ones that dwell out of direct sunlight. Allen has christened this variety the albino Salvador.

The larger sponges extrude into the bay from Gorontalo’s ocean-facing walls in a seeming act of defiance against the currents, however living in such an exposed location is not without its hazards. Occasionally even the mighty Dali succumbs to the rigours of ocean life, lose their grip on the wall and tumble away to the depths.

Sadly, once fallen onto the seafloor, these giants can no longer filter enough nutrients to survive. Within a few weeks, the once rock-hard sponge begins to crumble, dissolve into dust and disappear without a trace.

Emphasising just how unexplored these waters are, no one has yet documented how far along the coastline this phenomenon occurs on this species. However, it is known that by the time you reach Lembeh Strait or even the nearby Togian Islands, the morphing of Petrosia lignosa cannot be observed.

Allen recalls in his highly acclaimed book, Gorontalo: Hidden Paradise, of when he first confirmed the identity of the species.

“Even though I was calling it the ‘Salvador Dali sponge,’ I suspected it had to have a proper name. So, we sent samples from two sponges to Nicole J. de Voogd of the Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, Zoological Museum, University of Amsterdam. After looking at the maze of spicules under a microscope, she was able to identify it as Petrosia lignosa.

Our sponge expert says that the genus is aptly named since petrosia means ‘stony hard’ and all Petrosid sponges are hard and rock-like. This particular sponge species is peculiar to vertical walls in Indonesia. The wildly carved surface is a morphology only known to Gorontalo. Divers can only see the Salvador Dali sponge here.” [2] said Allen.

Local stewardship

The steep drop of the seabed has had another significant benefit, in helping to preserve Gorontalo’s pristine reefs and coastline. The fishermen here are able to deploy handlines from their traditional outrigger canoes and wrestle with species normally found offshore, such as the yellowfin tuna.

Coupled with a lack of horizontal reef surface area, this has negated the appeal of enormously destructive practices such as blast fishing, a scourge of reefs in some parts of Indonesia.

The fish stocks are also protected by the huge waves that come when the winds change from westerlies to easterlies between May and October, imposing natural no-take zones as much of the coastline becomes inaccessible.

Finally, the reefs of Gorontalo have found ally in a group of forward-thinking individuals who recognize that education is the best long-term defence against poor fishing practices. For the last ten years this group, which comprises representatives of the local government, students, and staff from Miguel’s Diving Centre, have conducted regular public education campaigns to deliver one simple message: “No coral, no fish, your choice.” The message has hit home with many of the villages now showing evidence of deep-rooted respect for the marine environment on which they are so dependent.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the villagers of Olele who have really taken governance of the reefs to their hearts. Having already established a village level Marine Park, they guard and police their own reef, driving away any unwelcome visitors, sometimes even confiscating their equipment.

The recent expansion of the park's boundaries has been observed to have led to a noticeable rise in the number of large groupers, particularly coronation lyre-tailed and tiger, plus large midnight snappers. Populations of schooling fusiliers have increased also, further re-enforcing the value of good marine stewardship.

Finding a balance between long term sustainability and short term gain will continue to be a challenge for many other parts of Indonesia, yet the developed world has failed on a far grander scale to get to grips with this dilemma. Whilst modern fishing fleets efficiently vacuum the oceans, industry policing groups all too often prove ineffective in leading positive change. Often heavily influenced by commercial agendas, their mandates are frequently distorted by those pushing for short term profit rather than leaving a world that is fit for our descendants to inhabit.

Curiously, the human race continues to behave in a way that is at complete odds with one of our strongest individual natural instincts, that of protecting our children at all costs. Yet on the surreal shores of Olele village in Gorontalo, the enlightened community has taken a huge step towards finding that balance. ■

The author wishes to thank Rantje Allen, the staff of Miguels Diving Centre, Gorontalo, (www.miguelsdiving.com) and the people of Olele village. More of Steve Jone’s work can be seen at www.millionfish.com