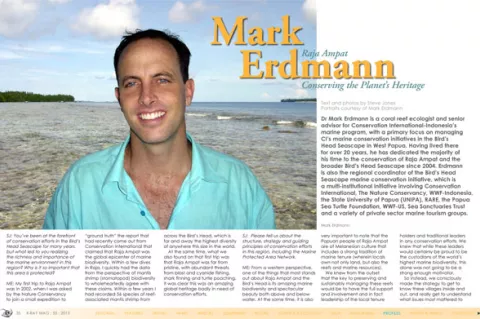

Dr Mark Erdmann is a coral reef ecologist and senior advisor for Conservation International-Indonesia’s marine program, with a primary focus on managing CI’s marine conservation initiatives in the Bird’s Head Seascape in West Papua.

Contributed by

Having lived there for over 20 years, he has dedicated the majority of his time to the conservation of Raja Ampat and the broader Bird’s Head Seascape since 2004. Erdmann is also the regional coordinator of the Bird’s Head Seascape marine conservation initiative, which is a multi-institutional initiative involving Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy, WWF-Indonesia, the State University of Papua (UNIPA), RARE, the Papua Sea Turtle Foundation, WWF-US, Sea Sanctuaries Trust and a variety of private sector marine tourism groups.

Steve Jones / X-Ray Mag: You’ve been at the forefront of conservation efforts in the Bird’s Head Seascape for many years, but what led to you realizing the richness and importance of the marine environment in this region? Why is it so important that this area is protected?

Mark Erdmann: My first trip to Raja Ampat was in 2002, when I was asked by the Nature Conservancy to join a small expedition to “ground truth” the report that had recently come out from Conservation International that claimed that Raja Ampat was the global epicenter of marine biodiversity. Within a few dives in Raja, I quickly had the data from the perspective of mantis shrimp (stomatopod) biodiversity to wholeheartedly agree with these claims. Within a few years I had recorded 56 species of reef-associated mantis shrimp from across the Bird’s Head, which is far and away the highest diversity of anywhere this size in the world.

At the same time, what we also found on that first trip was that Raja Ampat was far from pristine, with abundant threats from blast and cyanide fishing, shark finning and turtle poaching. It was clear this was an amazing global heritage badly in need of conservation efforts.

SJ: Please tell us about the structure, strategy and guiding principles of conservation efforts in this region, including the Marine Protected Area Network.

ME: From a western perspective, one of the things that most stands out about Raja Ampat and the Bird’s Head is its amazing marine biodiversity and spectacular beauty both above and below water. At the same time, it is also very important to note that the Papuan people of Raja Ampat are of Melanesian culture that includes a strong tradition of marine tenure (wherein locals own not only land, but also the reefs and marine resources).

We knew from the outset that the key to preserving and sustainably managing these reefs would be to have the full support and involvement and in fact leadership of the local tenure holders and traditional leaders in any conservation efforts. We knew that while these leaders would certainly be proud to be the custodians of the world’s highest marine biodiversity, this alone was not going to be a strong enough motivator.

So instead, we consciously made the strategy to get to know these villages inside and out, and really get to understand what issues most mattered to them, and then try to couch our marine conservation thoughts in terms that mattered to them.

What we found almost immediately was that the local communities were very concerned about their food security and the fact that outside fishers were pillaging their resources. So, when we introduced the idea of a network of marine protected areas, it was not as a tool to protect marine biodiversity, but rather as a way to legally strengthen their marine tenure claims and give them full management authority over their marine areas, restricting the access to outside fishers and thereby ensuring their long-term food security.

We then took the unprecedented step of recruiting the MPA managers and staff directly from these local communities—and while this meant that we were mostly getting staff with 2nd and 3rd grade educations, they were nonetheless intimately familiar with their resources, highly passionate about saving them, and we of course targeted local community members with strong leadership skills.

It meant we needed to invest a long time (five years or so) in training them in marine biology, marine resource management, and even basic computer skills, but the end result has been fantastic, and we are confident will mean that this initiative is truly sustainable, having built a strong local foundation.

We could have instead brought in outside talent comprised of well-trained Indonesians with university degrees, but not only would they likely not be very accepted by local communities, they also wouldn’t have the intense passion to save their own reefs, and they would over time of course want to return home to their families in Jakarta or wherever.

It took a bit longer to train local community members instead, but the result—we believe—will be ultimately more sustainable. Local communities therefore play the primary role in managing the reefs of Raja Ampat—this is a 100 percent local affair.

SJ: What alternatives exist for local fishermen and villagers currently engaged in destructive practices? What incentives are in place to help them pursue more sustainable practices?

ME: As for providing alternatives for local fishers engaged in destructive practices, if I may be blunt, I have learned over two decades in Indonesia that this is a romantic and foolish notion. Destructive practices like bomb fishing are illegal, immoral, and rob coastal communities of the future of their fisheries and any tourism potential.

In any given community, it is only a minority few that are actively engaged in these destructive practices, and they should not be “rewarded” by being given special treatment to seek alternatives. This may sound harsh, but my views have been shaped by the very strong and angry words of the many coastal villagers who DON’T participate in destructive practices and are having their futures pillaged by these criminals.

Blast fishing and cyanide fishing are marine environmental crimes, and they need to be treated as such. Police are not expected to provide “friendly alternative livelihoods” to drug dealers or child traffickers, and in my opinion, bomb fishers fall into this same category. Quite frankly, one can NEVER come up with an alternative that easily makes them as much money—this is a lost cause.

We prefer to focus on empowering and protecting those fishers engaged in sustainable practices, and the “bad guys” simply need to adapt or get sent to jail.

As Raja Ampat’s reefs continue to improve in quality, there are many more opportunities for local villagers to derive benefits from marine tourism, aquaculture and sustainable fisheries—and those opportunities are available to all.

SJ: How are conservation efforts able to benefit local communities in the short term? Do you think communities see the link between conservation and these immediate benefits?

ME: As I noted above, the conservation program in Raja Ampat has been developed WITH the local communities to answer their most pressing concerns of food security and empowering their traditional rights of tenure and resource management. Protection of biodiversity is a handy side benefit, but this is not the primary goal of Raja Ampat’s MPA network and conservation initiative.

The main aims are to ensure food security and long term sustainable livelihoods from the marine resources and to provide additional legal support for them to exclude outside fishers from utilizing their resources. These benefits are more or less immediate and only continue to grow, and it is clear that the villagers of Raja Ampat “get it”—in that we continue to get requests to expand the boundaries of the MPAs or create new MPAs in areas that are not currently protected.

SJ: Does conservation feature in the day-to-day education within schools and do schools currently teach the value of the marine ecosystem for the long term well being of the Indonesian nation?

ME: One of our flagship programs in Raja Ampat has been the Kalabia program. You can also see more about it at the following link: blog.conservation.org

The Kalabia (named after Raja Ampat’s endemic walking shark) is a converted 34m tuna longliner that now travels around Raja Ampat to each of the 130-plus villages, delivering a three-day customized experiential conservation education program for elementary school children. On board are six highly-dedicated environmental educators (again, local community members that we recruited and trained intensively) who bring this program to the communities.

The climax of the three-day program is when the children are all taken snorkelling on their reefs, and they also do mangrove and seagrass bed walks and learn all about MPAs and their benefits, the ecological values of sharks, etc.

At night, the whole community comes down to the village dock to watch the videos shown by the Kalabia team. It is a fantastic program. The teachers from the local schools are all included in all activities, and we leave the curriculum materials with all the school teachers so that they can continue to use them in their classrooms after the Kalabia leaves.

SJ: What are the notable successes so far and what remain the top threats to the region that will be focused on in future?

ME: I reckon the biggest success has been the setting up of this network of over 1.2 million hectares of the most biodiverse reefs on the planet, which are now being actively managed by local community members and strongly and passionately enforced. We’ve seen numerous outside bomb fishers and shark finners actually put in jail, and the reefs, fish and sharks of Raja Ampat are actively recovering.

I also believe this is reflected in the dramatic increase in marine tourism development, which we’ve actively encouraged—going from one resort and one liveaboard and about 300 guests a year in 2000 to now 40 liveaboards, seven resorts and about 7500 guests a year.

The Raja Ampat entrance fee system is now raising over US$350,000 per year. The Raja Ampat government now actually believes that marine tourism and sustainable fisheries can be the motors of its economic development, and has forsworn any further mining development. And we’ve cemented this in the West Papua spatial plan, which prioritizes Raja Ampat as a region for marine tourism, marine conservation, and sustainable fisheries and aquaculture and NOT industry and mining as with much of the rest of Papua.

I also note that overall, incidences of blast and cyanide fishing have decreased dramatically. We’ve largely addressed turtle poaching (especially in the main nesting beaches) and the recent passage of the regency law declaring Raja Ampat a shark and ray sanctuary gives strong legal teeth to the ban on fishing sharks and rays.

In terms of ongoing threats, interestingly enough, they are now coming more from the land than from the sea. We continue to have the issue that as shark populations have stabilized and even started to increase in the best protected areas (Misool, Wayag), they are increasingly a beacon to illegal shark fishers from across Indonesia. But this we can hopefully deal with.

More concerning though are the impacts of the ongoing land-based coastal development in Raja Ampat - especially road construction in Waigeo and various and other plans for airports and even transmigration camps on other islands. There is a major influx of immigrants into the capital city of Waisai, and this is a concern both in terms of carrying capacity as well as dilution of cultural traditions.

We’ve also seen a huge increase in plastic and other trash in the oceans, mostly coming from both Waisai city and Sorong—both of which are growing very rapidly with immigration. These are all new challenges that we are having to adapt to.

SJ: Given its position at the epi-centre of marine biodiversity, what will be the likely cascading impact to other regions, if the Bird’s Head marine environment is not successfully managed?

ME: Raja Ampat and the Bird’s Head act as a repository of a mind-boggling percentage of the Earth’s coral reef biodiversity. With over 600 species of hard coral, this region alone is home to approximately 75 percent of the world’s hard coral species! So it is imperative to protect and manage this.

We moreover hypothesize that this region is, in fact, an active cauldron of evolution, or “species factory”, which is, as we speak, still generating novel biodiversity. As diversity provides the building blocks for adaptation to global change (climate, etc), it is imperative to maintain as much diversity as we can to give reefs and, in fact, humans the best chance of surviving the coming changes facing our planet. If the Bird’s Head is not properly managed, we’ll lose this repository of diversity.

SJ: Conversely, how does the conservation programme in the Bird’s Head Seascape benefit other regions in the Coral Triangle?

ME: Obviously, if we can properly manage the Bird’s Head, we’ll keep this diversity available for adaptation to global changes.

But there are other benefits of proper management of this area as well. The Bird’s Head continues to serve as an “incubator” region for testing new management approaches, including the strategy I elaborated above about heavily investing in building the capacity of local villagers to manage their own resources on a large scale.

But there are a number of other new initiatives being tested in the Bird’s Head, including the first shark and ray sanctuary in Indonesia and the Coral Triangle, the most successful tourism entrance fee system in the Coral Triangle (in terms of annual revenues), the first real marine tourism management regulations in Indonesia (including a licensing system that caps the number of liveaboards able to operate, etc), and the first attempt to gazette a comprehensive MPA network of seven MPAs within a single regency.

Besides serving as a management “classroom” (the lessons learned from which are now being shared around Indonesia), Raja Ampat’s position at the top of the “Indonesian Throughflow” of waters from the Pacific towards the Indian Ocean means that having healthy populations of reef fishes and other organisms here can actively “seed” other reefs in eastern Indonesia due to the strong currents passing through Raja Ampat and towards the Maluku spice islands.

SJ: It is known this area has suffered heavily from shark finning practices. Do you think the region will ever be able to recover its shark populations or have we passed the point of no return?

ME: I am exceedingly positive about the situation with sharks in Raja Ampat. The area has indeed long suffered from shark finning; my neighbours in South Sulawesi when I was doing my PhD work in the early 90’s were actively finning around Raja Ampat even back then. However, Raja Ampat has now implemented the first shark and ray sanctuary in the Coral Triangle (across all of its waters), and the regency law #9/2012 (passed in December 2012 and announced in February 2013) provides serious legal sanctions (and NO LOOPHOLES!) for anyone catching, injuring, transporting, molesting, or in any way exploiting sharks and rays in Raja Ampat.

We, of course, need to work hard to make sure this is broadly socialized and effectively implemented, but I am confident the government and communities are up to this challenge as they understand how important sharks and rays are both to healthy reef fisheries but also for marine tourism.

In the areas of Raja Ampat that have already been strongly protected for the past three to five years (e.g. around Misool EcoResort, Cape Kri near Papua Diving, and the Kawe-Wayag MPA), we can already see significant recovery of shark populations. Max Ammer at Papua Diving has now several times tried putting down bait (minced tuna) off his dock and within five minutes has had up to 30 adult blacktip sharks racing around.

Around the reefs near Misool EcoResort, it is now possible to see silvertip sharks or sometimes three to five grey reef sharks—something you would never see even four years ago. It will take time, but recovery is underway.

SJ: Finally, what is your perspective on the overall outlook for Raja Ampat?

ME: Bright! There are still a number of challenges facing Raja Ampat, but I strongly believe that because we were able to initiate these conservation programs before the current wave of development washed over Raja Ampat, that the communities are now sufficiently aware of the threats to their resources that much of this development poses, and they are now empowered to make their own decisions about the future management of these resources. We’ve done our best to train them to be good stewards, and I optimistically believe this will allow Raja Ampat to continue to improve its management and the quality of its marine environment.

— Dr Mark Erdmann has published 107 scientific articles and four books, including most recently the three-volume set, Reef Fishes of the East Indies, with colleague Dr Gerald Allen. Erdmann was awarded a Pew Fellowship in Marine Conservation in 2004 for his work in marine conservation education and training for Indonesian schoolchildren, members of the press, and the law enforcement community. Erdmann lives with his wife Arnaz and three children in Bali, and maintains a deep personal commitment to do whatever is necessary to ensure his children will be able to enjoy the same high-quality underwater experiences that continue to provide the inspiration for his dedication to the marine environment. ■