Through the centuries in Greece, Kea Island’s renowned statue, the Lion of Kea (one cannot see him from the shore, but I know he is there), continues to smile and look askance upon human vanity—exactly the same way he did in 1916, when during World War I, hospital ships were hit by mines and tragically sank in the Kea Channel. These ships, now wrecks, include HMHS Britannic and SS Burdigala.

Contributed by

It’s July, 2015, Greece. It’s very hot outside. Television commentators from various countries are passionately informing humanity that Greece is ready to leave the European Union, and an inevitable collapse shadows the nation. Here, on Attica, there is still some tranquility and serenity to be found, as is usual for this historical region encompassing Athens. Maria, the taxi driver taking me to the ferry in Lavrio, complains: “Business is very slow. But who said that life is easy?”

After an hour’s journey on azure seas, I reach Kea Island and find everything there even more relaxed. Visitors are met with hugs and kisses, and friendly shouts, and as the cars, disembarking from the ferry, leave the parking lot, a tranquil atmosphere settles over the port.

U-Boat Navigator

The captain of the Russian-Ukrainian-Maltese crew, Olexandr Stasyukevych, welcomes me onboard U-Boat Malta’s research vessel, Navigator. The wrecks of HMHS Britannic and SS Burdigala are the subjects of research for the first stage of a joint expedition between the Center for Underwater Research of the Russian Geographical Society and the company, U-Boat Malta. U-Boat Malta provides services to organizations in the fields of marine archaeology, scientific and historical research, as well as film. The company’s playground is mainly the Mediterranean, but is not limited to this region. This time, it is the Aegean Sea.

Navigator’s captain, Stasyukevych, is a celebrity in the yacht world; besides being a successful racer and coach, he took part in an epic journey onboard the yacht, Scorpius, in a “circulation of 33 seas”—bypassing both poles in one navigation. On the same crew of the Scorpius was, by the way, Sergey Bychkov, who is also a doctor aboard the Navigator. All the Navigator crew members—the boatswain, Sergey Zhdanovych; the chief engineer, Joseph Calleja; the engineer, André Tanti; the electrician, Sergii Zakharov; the cook, Alexey Leonov; the deep divers Levan Margishvili and Andrey Likhanskiy—possess the absolute top, professional qualifications in their fields, and at the same time, do not shun any work onboard; this is the way things are done here. Everyone is a sailor, first of all.

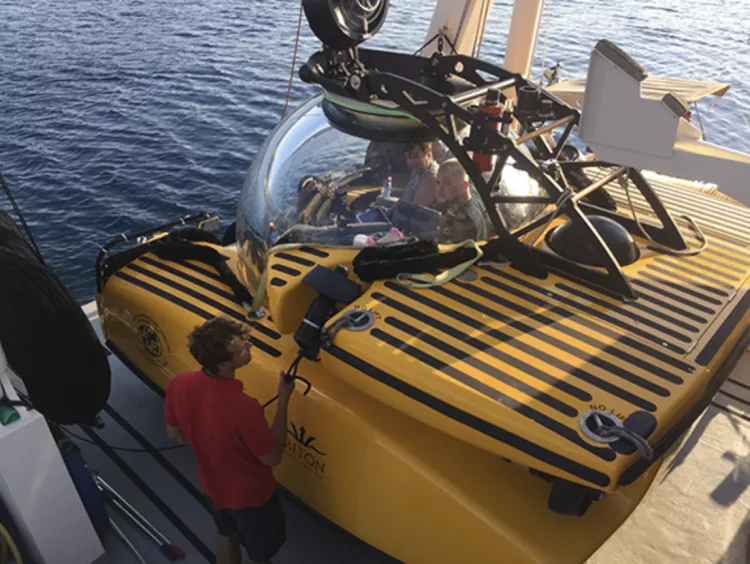

Aboard the Navigator, I was struck by the quantity of various equipment, packed into every cubic meter of ship. There was a remotely operated vehicle (ROV)—an Ageotec Perseo GTV for visual and instrumental inspections—and the Triton 3300/3 submarine, able to work at 1,000 meters depth. There was also sonar equipment, winches, diving equipment, including a compressor and gas blender, and a full medical complex, including a hyperbaric chamber—a dream dive boat for any technical diver.

Off to the sea we go! Here, for nearly 100 years, in direct view of Kea Island’s shore, in the channel between Kea and Makronisos, rests the legendary ship Britannic.

Britannic

The British shipping company White Star Line’s third and largest Olympic-class ocean liner, HMHS Britannic was the sister-ship of RMS Titanic and RMS Olympic. Britannic was supposed to enter service as the transatlantic passenger liner, RMS Britannic. The vessel was launched just before the beginning WWI, however, she sat out of action at her builders in Belfast for several months before becoming a hospital ship in 1915. On the morning of 21 November 1916, Britannic hit an underwater mine off the Greek island of Kea in the Kea Channel, and sank 55 minutes later killing 30 of the 1,066 people on board.

There were 1,036 survivors pulled from the water onto lifeboats; after about an hour at 9:07 a.m., the Britannic sank. Even though Britannic was the biggest ship lost in WWI, it was not the most costly in terms of deaths compared to the sinking of the Titanic or the Lusitania, or many of other vessels lost during WWI.

Divers often call this wreck the “Underwater Everest”, stressing the unique features, dangers and complexity involved in diving the Britannic, which rests at a depth of 120m. Indeed, the number of people who have visited this magnificent ship underwater is less than the number of those who have gone to outer space. Diving Britannic is extremely difficult, demanding good preparation and technical diving knowledge as well as technical support. Navigator provides everything for this purpose: deep divers on staff, technical diving equipment, 100m operating diving bell with a hot water supply—so divers can be warm and comfortable during the five to six hours of decompression.

ROV and Triton submarine

But the most interesting features of this expedition are the primary “divers”—the ROV and the Triton submarine—as the main goal of the expedition is to get high-quality footage of HMHS Britannic and other deep wrecks for research purposes and for the series of film documentaries entitled Dark Waters. Part one, entitled “Red Crosses on the Water: Hospital Ships of WWI”, is dedicated to the 100-year anniversary of the sinking of HMHS Britannic.

The Triton submarine is used as a “housing” for the 6K RED camera, while also carrying a cameraman and a pilot. The pilot, Dmitry Tomashov, has spent over 40 hours on Britannic—an unprecedented record—and contributes his vast experience and invaluable knowledge on the subject to the expedition. The cameraman, Eugene Tomashov, has even more experience. Dima and Eugene, comprise a magnificent father-and-son team, operating seamlessly and understanding each other perfectly well.

Diving and filming the wreck

The ship is 260m long, with a maximum depth of 120m. The wreck is done consistently, from bow to stern or from stern to bow, depending on the current. At least two to three shifts are necessary to cover the wreck, during which Navigator moves its anchors, relocating the ROV. Eugene films close-ups, highlighting details of the wreck. This year, during the third expedition season in a row, the team succeeded in shooting general views of the wreck in order to see the whole ship at a glance. This imagery was made possible by special shooting technology, with the submarine and the ROV working together, to direct a large amount of light onto the subject. The director of photography of the project, Sergey Machilsky—well-respected in Russian cinematography—is an experienced professional and also a diver, himself.

After several expedition seasons, the team has carried out about 50 hours of shooting Britannic, capturing several terabytes of footage. What is the reason for this? HMHS Britannic is a real movie star—nearly as famous as her sister-ship, Titanic. Eugene Tomashov, the expedition leader and project developer, is a professional deep-water diver, underwater operator and scriptwriter. He has investigated and filmed hundreds of wrecks, and he is very passionate about documenting underwater wrecks. The Britannic wreck, like many deep wrecks, is disappearing over time. Water and marine organisms are doing their job and taking their toll on the ship’s remains. In time, this gorgeous ship will turn into piles of dust. So, it is necessary to show Britannic as she is now, and once again, remember her legendary and tragic story. ■