Utila is the smallest of the Bay Islands off the coast of Honduras, where divers go in search of whalesharks, but find much more. Being the Executive Director of The Manta Network, a global conservation organization, I was very interested in the local efforts to protect whalesharks. Patric Douglas, Director of SharkDiver.com, invited us to stay in Utila and write about his dive group’s whaleshark experiences.

Contributed by

I welcomed the chance to also investigate pelagic animal field research and local conservation efforts. Whalesharks are the largest of all sharks and are the largest fish in the sea. They can grow to more than 50 feet long and feed on plankton, which are some of the smallest organisms in the ocean. These highly migratory animals are capable of sustaining high speeds yet usually display a leisurely grace.

These gentle giants show no fear of humans but have been mercilessly exploited and are now on the World Conservation Union’s Threatened Species list as vulnerable to extinction. CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) has also listed them in an effort to protect them from the international trade of whale shark products.

Several worldwide manta ray programs have recently been initiated and we are taking many of the same directions as global whale shark conservation efforts. I received several reports saying that Utila was the best place to see manta rays on the Caribbean side of Central America. Only a few months earlier in Roatan, another of the Bay Islands, I was able to obtain some footage from a local photographer who was lucky enough to catch a rare glimpse of manta rays. Therefore I was eager to see what I could find in Utila.

During our stay, we learned more about the problems that face Utila than could possibly be imagined. One of the main attractions of this island is the opportunity to be in the water with whale sharks. However, this eco-tourist experience is being threatened by many factors. The number of dive boats racing to see each whale shark that surfaces were creating a dangerous and chaotic situation.

Whalesharks were being disturbed, snorkelers were being hurt and fishermen were angry because the presence of so many dive boats affected their ability to fish. There was a report of local fishermen who had purposely killed a whale shark. They were threatening to kill more in order to stop the dive boats from surrounding the boils of jumping tuna where the whale sharks surface to feed.

The government is trying to decide on what actions to take and the biologists are trying to establish guidelines for all the dive operators to follow in order not to frighten the whale sharks away and to give them space to feed.

There are two local groups researching whale sharks on Utila. Jim Engle, who runs the Utila Lodge and BICA (Bay Island College of Diving), has been studying whale sharks for more than 12 years. In the last few years, he has also been working with SRI (Shark Research Institute). He has now established an independent research and conservation organization called WSORC (Whale Shark Oceanographic Research Center) and has started a tagging program.

Another resort and dive operator, Deep Blue, has also begun to collect information about whale sharks. They are working with Ecocean, a whale shark conservation group in Australia that has created a Global Photo ID Library. The library consists of a visual database of individually catalogued whale sharks and encounters. It is maintained and used by marine biologists to collect and analyze whale shark data in order to learn more about the behaviour of these amazing creatures.

Dynamics of a Boil

A boil (also known as a bait-ball) is an area on the water’s surface that has so much activity of fish jumping and splashing that it resembles boiling water. This is where we can find whale sharks, other types of sharks and even manta rays. Jim Engle has found that only the boils containing bonito tuna are where the whale sharks feed.

There are two schools of thought on how a boil is created: one theory is that the whale harks create the boil themselves and the other is that the boil is created and the sharks use their superior senses to locate the bait-ball.

It is possible that the whale shark may first locate food and then circle from the depths to force the baitfish upwards. Circling ever closer, the fish are concentrated and are forced to the surface. When the boil has sufficient density, the whale shark opens its mouth and a ton of small fish cascade down into its waiting gill rakers.

The other theory is that the whale shark may sense a boil from far below and ascend directly into its centre. Whalesharks have cartilage spines that run the length of its body. Some biologists believe that these spines are sensing devices and can accurately pinpoint an active boil. Tuna circling the small fish may be responsible for creating the boil.

Whaleshark Tagging

We were invited by Jim Engle to participate in the tagging of a whale shark. Luke Tipple, a young and energetic biologist working for WSORC, spearheads the tagging program. Luke has a BSC in Marine Sciences and has been studying whale sharks since coming to Utila from Adelaide, Australia. In the last three months, he has successfully tagged at least ten whale sharks.

Luke is also planning to take tissue samples for DNA analysis to learn about the relationship of Utila’s whale shark population to that of other areas around the world. These samples will be sent to Ecocean and will combine with other data to build a picture of the whale shark's family tree and possibly their long-range migration behaviour.

Using a three-band spear gun, visual identification tags are attached just below the dorsal fin. These white or yellow tags are large enough to be visible from a distance. Luke is a highly accurate shot, having grown up free diving and spear-fishing. He can place the tag at precisely the best location for reading without hurting the animal. Shooting the tag into its thick skin requires a lot of force but it does not harm the whale shark.

With cameras in hand, we spent the better part of a day searching the waters on the north side of Utila for surface boils. Birds gathering from a distance signal the creation of a boil. Not all boils attract whale sharks so we had to be very patient.

On our second encounter, Luke successfully attached tag No. 0173 to a small 20-foot whale shark, but did not determine its gender until a later dive. We then recognized the whale shark by its tag and my photograph determined that it was a female. Filing the sighting report and photograph with Ecocean‘s on-line global database is the first step in the identification process.

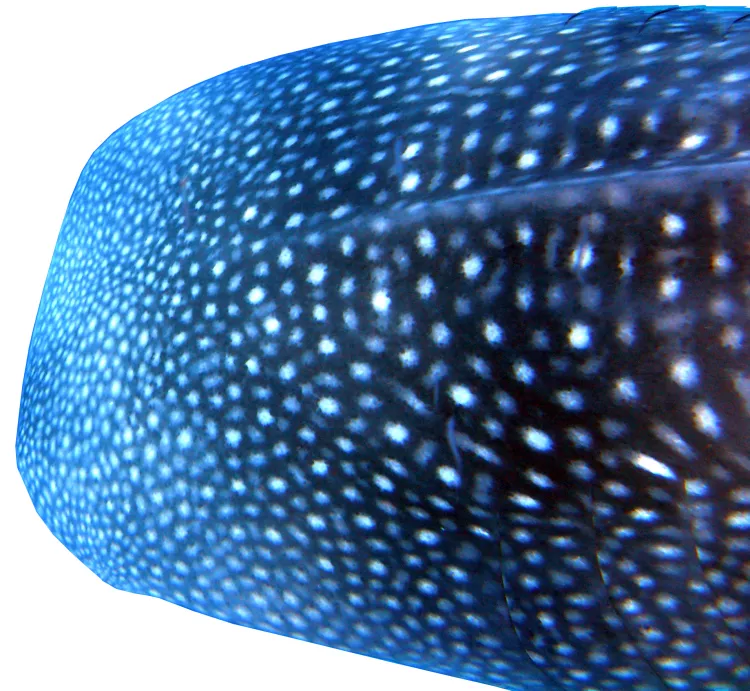

Spot Pattern Recognition

The Ecocean Library began in 1995, building on the research of Brad Norman at Ningaloo Marine Park, Western Australia. Every whale shark has a unique pattern of white spots on its grey skin. The spot pattern behind the fifth gill on the left side is used to document whale sharks. Any scars also help to distinguish between individual animals.

In 2002, Jason Holmberg established the Shepherd Project, which has enabled the library to grow through sighting submissions from research, conservation, and eco-tourism communities around the world. As part of Ecocean’s global database of whale shark sightings, they have developed image-processing software that performs pattern matching on the whale shark's spots.

The best way to spot whale sharks is from the air. On three occasions, Patric hired a scouting plane. We circled and watched while flocks of birds and dive boats converged below. When viewed from above, the whale sharks look like large catfish in the blue water below.

While snorkelling with Patric’s group, we captured some images of whale sharks underwater, one of which clearly showed the spot pattern behind the fifth gill on the left side. We submitted the image data and learned that we had identified a new animal, now nicknamed Lynn Jaye for the photographer. These activities will lead to insights into whale shark migratory behaviour and will make possible the development and establishment of better conservation practices.

Rules of Encounters

The whale sharks off the coast of Utila exhibit behaviour very different from anywhere else in the world. It is believed that they may be shyer because they are juveniles. Here, the sea is nearly a half a mile deep and encounters take place in the deep blue water. Whalesharks dive quickly when they are startled or have finished feeding. It is for this reason that tourists are only allowed to snorkel with them. It is feared that scuba divers will follow the whale sharks on their quick descent and lose track of their depth in the excitement of the chase.

It has been the practice in Utila for many dive boats to surround one unsuspecting shark. All of a sudden there can be as many thirty snorkelers in the water splashing and kicking. The young whale sharks are usually disturbed by the onslaught and immediately dive for the deep. Amidst the commotion, some of the snorkelers do not get to see the whale shark at all.

We accompanied Luke and his team on several tagging trips. On our second excursion, members of the Honduran Ministry of Tourism were on board. They were witness to several boats racing to get snorkelers in the water to see the whale shark before it disappeared. They were also on board when a dive boat steamed through the centre of the boil right over a whale shark and narrowly missing a snorkeler.

One day as we joined the snorkelers jumping into the water, a woman received a major injury consisting of a large gash on her calf, a fractured tibia and a huge bruise on the other inside thigh. Although no one actually saw one, it was guessed that a silky shark was responsible.

This has never happened before in Utila and hopefully, the new guidelines will prevent it from ever happening again. If this were truly a shark bite, it was probably not the shark’s fault as the woman may have accidentally jumped right in its path or on top of it, or it would not have bitten her. It probably only did so in defence.

Obviously, whale shark eco-tourism will not be allowed for long unless strict rules for the safety of sharks and snorkelers are established and enforced.

New rules for whale sharks encounters were drawn up by Luke and his team at WSROC and were modelled after those initially developed by Ecocean. These include creating a 600-foot diameter contact zone around the whale shark in which only one boat, designated by a special flag is allowed at a time.

Only a maximum of eight snorkelers are allowed in the water at a time and entry must be made as quietly as possible. Touching, riding or obstructing the path of the whale shark is not allowed nor is the use of flash photography. The ten guidelines were approved by the local dive association but are yet to be fully adopted by everyone.

Politics and Education

As with most small island politics, the needs of several groups have to be carefully balanced. Fishermen, dive operators, scientists and government all have their special interests. The Honduran Government is quickly becoming aware of the importance of the marine ecosystems and the value of whale shark encounters to the tourist industry.

However, Luke and the other marine scientists face an uphill battle to protect the young whale sharks. He is intent on educating and building awareness through sound eco-tourism principles. These include programs to educate and integrate the fishermen, dive operators and the island’s children, who are often found catching the rare seahorses which are dried and sold to tourists.

Producing informative materials for each group is important but they must also be convinced of the economic benefits. The fishermen need to realize that over-fishing will lead to a complete collapse of the food chain, causing the reef to die along with their livelihood. This has already begun as most of the grouper, barracuda and snapper have been over-fished. Algae have proliferated, suffocating parts of the reef and affecting the diminishing population of reef fish. This situation is unaided by the lack of sewage treatment on the island.

Conservation

Conservation plans in Utila include rewards to fishermen for whale shark sightings. It is hoped that many fishermen will elect to become whale shark tour operators thereby earning a better income. In order to protect their economy, the fishermen and the dive industry must learn to work together. With the aid of the government and the scientists, they must learn to protect the entire marine eco-system including the whale sharks, the fisheries and the coral reef.

The Bay Island College of Diving, where Luke also works as a dive instructor, has been first to implement the guidelines that he proposed to the local dive association. We were there the evening Luke announced that they had been approved and everyone was jubilant. It is a big step towards safeguarding the presence of whale sharks in that area and the tourist economy that surrounds it. This was a large accomplishment for Luke, the young marine biologist who came to Utila to take on his first assignment after graduating from the University of Adelaide in Australia less than a year ago.

Once these safeguards are fully adopted and enforced, the whale shark encounters should prove to be more enjoyable and of longer duration. The dive operators must learn to understand that the guidelines will not only ensure that whale sharks return each year but that encounter times will be longer. This will lead to higher satisfaction for the divers and assure a growing eco-tourism industry.

Luke’s important work will help establish a baseline to determine whether Utila’s whale shark population may be declining. His data may also shed important insights into the health of the world’s populations.

Whale Sharks & Mantas

Manta rays are often seen in the vicinity of whale sharks in the deep waters that surround Utila. While waiting for a whale shark to surface within the boil, we spotted a large manta ray close to the surface.

This was the first time that we had observed two of the largest fish in the sea together. The possible interdependence of these two important pelagic species raises new questions as to their migration patterns and increases the importance of protecting their common food source.

In other parts of the world, mantas generally swim in the shallow waters over coral reefs and this also applies to whale sharks.

In Utila, it is extremely rare to see a manta ray in the shallow water and whale sharks are never found there. This suggests that the manta rays are not resident to Utila but are migratory and they may even accompany the whale sharks on their long pelagic migrations.

We left Utila with a new-found appreciation for the work being done there and for what lies ahead in our efforts to protect the world’s manta and mobula populations. The challenge we face obtaining scientific data to make the case for manta ray protection is only a small part of the ultimate conservation effort. Economic impacts, political meanderings and the need to balance local interests must be carefully weighed. In the end, we are all connected and must realize that biodiversity also includes human beings. ■

Published in

-

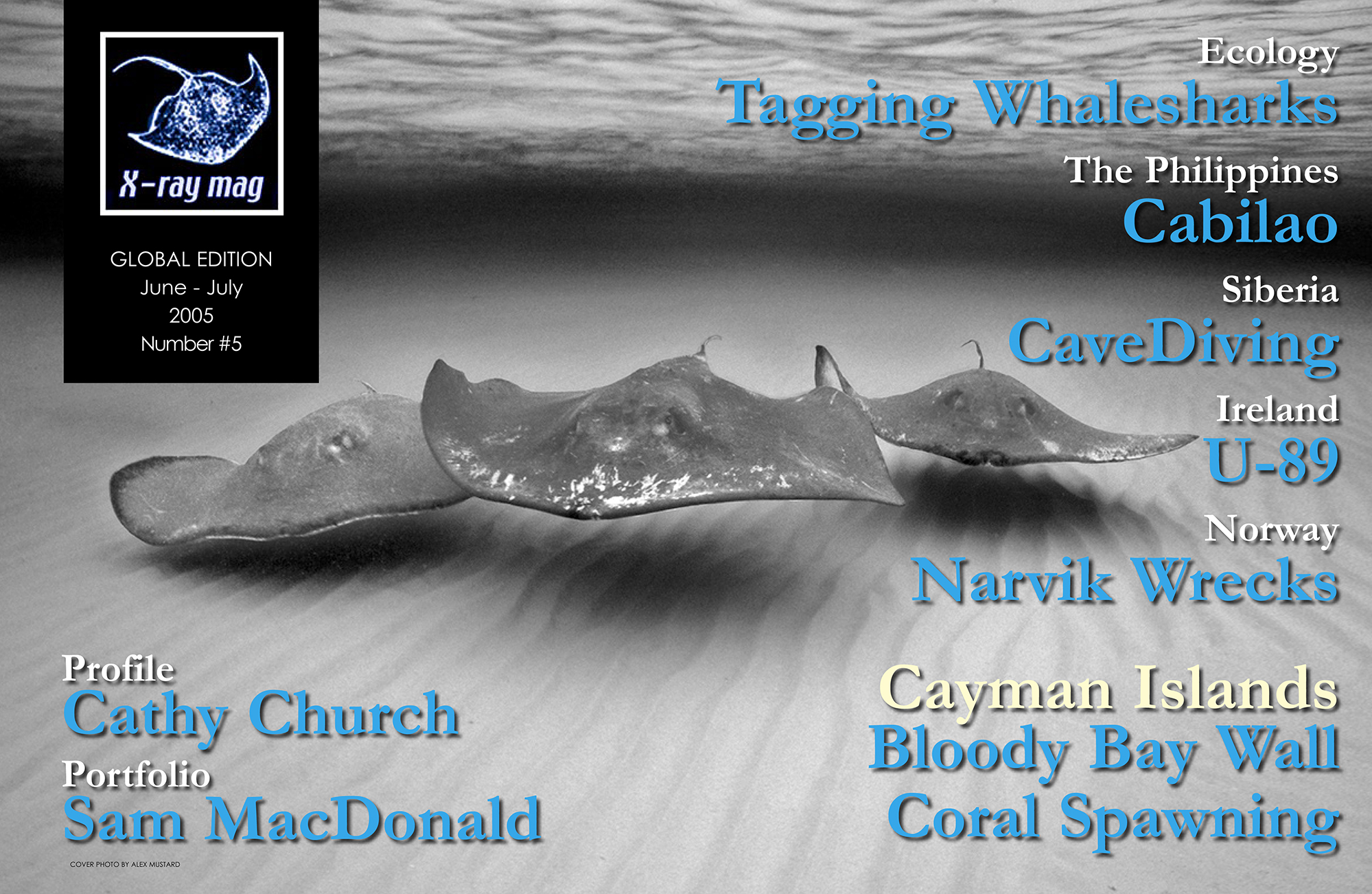

X-Ray Mag #5

- Read more about X-Ray Mag #5

- Log in to post comments