Slipping softly into the water, I had a straight path to the mother and calf that were resting near the surface only a short distance away. We closed the gap as quietly as a group of excited first-time whale watchers could manage and were rewarded with an initial glimpse of humpback whales from under the water. The newborn stayed close to its mother and swam up and over her rostrum as we looked on.

Contributed by

We stayed that way, frozen in the gaze of one another, for what felt like several minutes before mom slowly turned and gently guided the calf away. Her giant pectoral fin passed in front of my lens, and soon after, a massive tail came into view before gradually fading off into the distance. Our first encounter with humpback whales had been spectacular, albeit brief and entirely on their terms. We climbed back into the boat, animatedly talking with one another and excited for our next interaction with these breathtaking leviathans.

Our voyage began and ended at the Ocean World Marina, near the city of Puerto Plata, in the northeastern corner of the Dominican Republic. Trips run Saturday to Saturday over a 10-week season, which encompasses mid-January through early April each year. From the marina, our band of intrepid adventurers boarded a liveaboard dive boat and set sail for the Silver Bank, a marine mammal protected area and expansive, shallow underwater shelf located over 70 miles offshore in the Atlantic Ocean.

We were part of an exclusive group of approximately 600 annual visitors, as only three permitted boats are allowed on the Bank each season. Once moored at the sheltered anchorage, guests spend the next five days observing and intermingling with the densest population of North Atlantic humpback whales on the planet. Upwards of 4,000 whales migrate south each winter from their summer feeding grounds to mate and give birth in the warm and comparatively calm waters of the Bank.

About humpbacks

Growing to a length of 35 to 45ft (10 to 14m) and weighing approximately one ton (907kg) per foot, the humpback is the planet’s seventh largest whale. Females are larger than the males and whales of the Pacific Ocean grow 5 to 8ft (1.5 to 2.4m) longer than those in the Atlantic. Measuring nearly a third of the length of the whale, the humpback’s pectoral fins are the world’s largest animal appendage.

An irregular pattern of knobby tubercles along the trailing edge of the pectoral fins and tail fluke help redirect water flow and increase efficiency while swimming. Human engineers have copied that design pattern to create improved airflow on airplane wings, wind turbines and windmills. Similar tubercles on the whale’s rostrum and jaw have whiskers and nerve fibers that act as a sensory organ, unique to humpbacks. The arrangement of the tubercles on each whale can be used to aid in identification, as can the distinct patterning of black and white coloration on the pectoral fins and tail fluke.

Their scientific name, Megaptera novaeangliae, translates to “giant winged New Englander,” in reference to their large pectoral fins and their common sightings off New England in the 1900s. Humpbacks feed on krill and small fish by lunging, mouth open, at schools of prey and engulfing huge amounts of water. The water is then pushed out through baleen plates in the jaw to filter out their meal.

The whales do not feed while on the Silver Bank and use their fat reserves to survive the lengthy migration. A female can lose up to a third of her body weight while fasting during the journey and subsequent nursing of her newborn calf. It is estimated that only 50 percent of the humpback calves survive their first year, due in part to the gruelingly long migration route and the predators encountered along the way.

The sanctuary

The Silver Bank is part of a larger preserve called the Sanctuary of the Marine Mammals of the Dominican Republic. The sanctuary was established in 1986, expanded ten years later, and then again in 2012, and now covers an irregularly shaped area of over 40,000 sq mi (64,000 sq km). A series of shallow coral heads along the northeastern boundary act as a wave barrier that helps to subdue sea conditions, making it an ideal breeding and calving ground for the whales.

The 35 by 45mi (56 by 72km) Silver Bank was so named following the loss of a Spanish ship, laden with silver, which ran aground and sank on the coral heads in the 1600s. Voyagers must cross the Puerto Rico Trench, the world’s third deepest, at over 14,000ft (4,267m) to access the Bank, and the deep water is home to several additional marine mammal species including sperm whales, which are occasionally spotted during the transit.

Conditions

We arrived at our mooring on the Silver Bank to significantly different weather conditions than when we departed the previous evening. The sky was dark and ominous, and the wind and waves had picked up substantially during our overnight transit. The ocean’s surface was inundated in white caps from wind gusts that were consistently spiking between 26 and 29 miles per hour.

Regulations state that small boats are not allowed on the Bank if the wind is above 25mph, so we had to wait until the weather improved before venturing out to look for whales. Which is not to say that we did not see whales from the anchorage; we did, but we were unable to get up close or in the water with them. The day was spent getting to know our fellow passengers, preparing underwater cameras, assembling dry bags and snorkeling gear so we were ready when the wind dissipated. We also spent time learning about proper whale snorkeling techniques so we could make the most of our future interactions.

Rules, etiquette and procedure

Snorkeling is the only in-water humpback whale experience that is allowed at the Silver Bank. Scuba tanks or even diving down into the water column are prohibited. Guests are instructed to quietly enter the water and to stay together at the surface as they slowly make their way over to the whales. The guide enters the water in advance of the group and communicates with the skiff driver as to when the proper time is for the guests to join the festivities.

There are thousands of whales on the Bank, but the key is finding a cooperative whale before even getting into the water. Once a whale is located, frequently by detecting their exhalation spout in the distance, the skiff carefully approaches and attempts to stay with the whale while observing their behavior and breath cycles.

A mother and calf at rest are often the easiest to swim with because the mother, if comfortable with the boat’s presence, will stay down for 20 to 40 minutes between breaths while her baby surfaces every three to eight minutes. The calves are still learning how they fit in this world and are very curious about their surroundings, often leading to a close inspection of the flotilla of snorkelers at the surface. There is nothing that compares to the feeling of wonder and pure joy that sweeps over you while staring into the eye of a whale!

A typical day on the water starts with rolling out of bed to a fresh cup of coffee and a made-to-order breakfast before boarding the tenders around 8:30 a.m. to begin searching for whales. Rarely does one have to venture very far, typically less than a couple of miles, leaving the vast majority of the sanctuary solely to the whales and devoid of human presence. At some point in the middle of the day, the exact time being dependent on whale activity, the group returns to the mother ship for lunch before venturing back out for another excursion in the afternoon.

Sanctuary guidelines specify that visitors must be back at their liveaboards between 5:30/6:00 p.m., at which point cameras and gear are rinsed, showers are taken, and cocktails are served on the upper deck as guests enjoy the sunset and share stories from the day’s activities. There was often an after-dinner presentation in the lounge where we learned about humpback whale behavior, biology, natural history, environmental threats, conservation efforts and what we as individuals can do to help protect the species.

Day Two at the anchorage was spent waiting in vain for the wind to subside. Conditions improved in the afternoon but were still not conducive to venturing out on the water. The crew kept spirits high with frequent snacks, and guests were encouraged by repeated whale sightings. Throughout the day, several whales even came in close to say hello, and one whale treated us to numerous breaches during our sunset cocktail hour.

Humpback behavior

With so many whales on the Bank, there was almost always some sort of behavior to observe. The whales were socializing with one another, displaying courtship rituals, and in theory, mating—though neither the act of mating, nor the birth of a humpback whale, has actually been witnessed. Our efforts to decipher the meaning of these behaviors are purely theoretical but that does not diminish the fascination of watching the whales in action.

Breaching is perhaps the easiest behavior to identify as a whale launches itself headfirst, either partially or fully out of the water, before crashing back into the ocean with a large splash and often a twisting or spinning motion in midair. I have seen whales breach repeatedly, 20 to 30 times in a row without resting, and sometimes they breach once and are done. Equally impressive is a tail breach or peduncle throw, where the whale uses its large pectoral fins to stabilize its upper body under the water while launching its tail in a sideways thrust, resulting in a loud splash. Humpbacks are known to utilize this behavior as a defense mechanism against attacking killer whales.

Lob tailing or tail slapping is similar in that the whale swings its tail forward and back out of the water, smacking the surface with a boisterous splash. While laying at the surface, humpback whales can produce a similarly loud splash by slamming their massive pectoral fin or fins into the water in what is called a pec slap. The sound can be heard at great distances underwater and is likely some form of communication.

It is not advisable to be in the water during any of the above behaviors, but they make for fantastic photo ops from the safety of the skiffs. These behaviors would also make for great subjects for drone photography, except that unmanned aircraft are only allowed on the Silver Bank with prior permission and a special permit, typically granted solely to documentary film crews. I was not able to obtain a permit, but each of the three boats is allowed to fly a drone for self-promotional footage, and thus the aerial images included with this story are courtesy of Conscious Breath Adventures.

Simulations

We awoke to continued overcast and windy conditions on Day Three, though thankfully the gusts had diminished enough to allow us to head out on the skiffs to look for whales. After breakfast, we loaded up the small boats and commenced with a practice snorkel drill.

Sitting on the railing with our fins over the edge, the group waited for the boat driver’s instruction to enter the water, upon the go-ahead signal from our guide, who was already floating over to a make-believe whale. Permission granted, we eased into the water and slowly made our way over to the simulated whale, doing our best to remember to keep our fins under the surface, so as to remain as silent as possible and not disturb a real whale.

Mission accomplished, we began scanning the horizon for whale spouts amongst the white caps in hopes of utilizing our new-found skills. The opportunity to get back in the water did not materialize as we were hit with a rainsquall that reduced visibility to nearly zero. The wind picked up again over lunch, and we were unable to get back in the small boats until late afternoon.

Encounters

We had a wonderful up-close encounter with a mother, calf and escort as they let us follow along from the surface, though we were unable to get in the water. At the end of the day, as we made our way back to the liveaboard, a passing cloudburst produced a huge rainbow over the anchorage, instilling hope for a better tomorrow.

When a male is looking to mate with a female, he will stay in close proximity until she is receptive, which can be in as little as 10 to 14 days after she has given birth. The calves are born after a 12-month gestation period and are about a third as long as their mothers.

The primary suitor is called an escort, and each additional male that attempts to court the same female is labeled a challenger. When there are multiple challengers, all vying for the same female, the competition can be intense and is referred to as a rowdy group or a heat run. These clashes are more prevalent later in the season, when there are fewer females remaining on the Bank.

The males chase the female in an attempt to overtake the escort, all the while fighting with one another for position by slamming into one another with bodies, tails and pectoral fins and even attempting to prevent their opponents from rising to the surface for air. As a result, males will often have scars and battle wounds on their bodies that make them easier to distinguish from the relatively unblemished females. Humpback whales reach sexual maturity between five and eight years of age and are thought to have a lengthy 20- to 30-year reproductive life cycle, during their lifespan of around 70 to 90 years.

Threats

In addition to the challenges that humpback whales face from Mother Nature, sadly there are also multiple man-made threats to their existence. Commercial whaling decimated their population and drove the species to near extinction before the United Nations recommended a 10-year moratorium on whaling in 1972. The International Whaling Commission voted to further pause commercial whaling in 1982, but a loophole that allows for whaling in the name of research has been exploited by several nations, which continue the practice to this day.

Fishing gear and the threat of entanglement affects hundreds of thousands of cetaceans each year. Our consumer habits can assist on two fronts: by choosing to purchase sustainable seafood to help bring about the replacement of outdated fishing techniques with less hazardous methods, as well as curbing the demand for whale meat and blubber. Until such time as when fishing practices are no longer a threat, a global network of entanglement response teams has been established to attempt to remove the lines and nets from a whale once it becomes ensnared.

Shipping lanes that bisect whale migration routes and feeding grounds put whales at risk of being struck by ships, leading to injury or death. Research studies can help identify such interactions, and the findings can be used to advocate for changes to shipping lanes to protect the whales.

Finally, global warming, ocean acidification and pollution all negatively impact the very water the whales need to survive. Sanctuaries like the Silver Bank are critically important to the health of the species, and they need our continued support.

Displays and interactions

The weather continued to improve on Day Four and we were treated to a fantastic display as six to eight rowdy males chased a female shortly into our morning session. Multiple mother-and-calf pairings followed, but none were stationary enough to allow us to get wet.

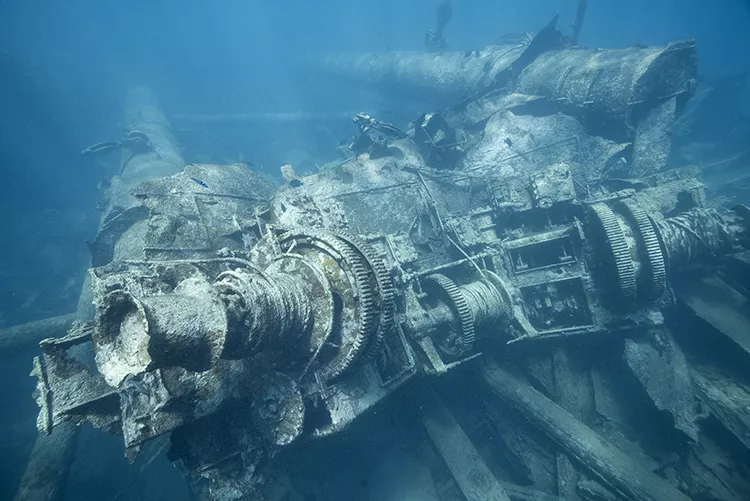

Just before lunch, we decided to explore the resident shipwreck, a Greek freighter named Polyxeni, which ran aground on the coral heads, decades earlier. Her rusty hull had remained largely above water until two recent hurricanes decimated her remains. It felt great to get back in the water and stretch our legs, even if we were not yet swimming with whales.

Our afternoon began with a brief encounter with a singing male moving slowly amongst the shallow coral heads, but unfortunately, he eluded us before we were able to get close enough to hop in the water. Finally, we came across the mother and newborn calf, whose interaction at the start of this story allowed us to ultimately see our first whales underwater.

The remainder of the day was spent on board the skiff in pursuit of a rambunctious calf who was repeatedly practicing its breaching, though not always successfully. It was fascinating to watch the calf attempt to emulate the behavior. We had hoped that it would eventually tire itself out, requiring mom and baby to stop and rest and allow us to get back in the water, but they never lingered. After more than an hour of watching and photographing them from the surface, we had to break off for the day and head for home. That evening, we enjoyed an outdoor BBQ and a night sky presentation on the upper deck. Stargazing while out at the Silver Bank is phenomenal due to the complete lack of light pollution.

Humpback songs

Humpback whales produce elaborate songs of clicks and whistles that can last up to 20 to 40 minutes and each tune is unique to the whales that inhabit a particular geographic region. The North Atlantic humpback whales have a different song than the humpbacks from the South Atlantic, which is different than the whales in the Pacific. Whales from the same population all sing the same song, though each whale sings in their own voice.

Cetaceans have no vocal cords and use a larynx-type structure in the throat to generate their melodies. They do not need to exhale to create sound, so the exact mechanism by which they sing is still a bit of a mystery. Most of the singers, or singing whales, are male and they frequently orient themselves with their heads down, vertically in the water column while singing.

If you are lucky enough to be in the water with a singer, not only can you hear the song, frequently you can also feel the sound waves as they resonate in your chest, arms or legs. Each person experiences the vibrations differently, depending on their own physiology. Every skiff has a hydrophone on board allowing guests to listen to the songs even when the whales are not close enough for snorkeling. We were fortunate to hear singers on multiple occasions during our trip.

Calm seas and curious calf

Our last day on the water began with blue skies, sunshine and the calmest seas we had experienced to date. Numerous whales were breaching and tail slapping on the distant horizon, and we took this as an encouraging sign of things to come.

The morning started slowly as we spotted a few spouts but had no luck finding a cooperative whale with which to swim. Around 11:30 a.m., we came upon a mother, calf and escort, which took interest in our boat and stayed in close proximity as we excitedly donned our snorkel gear in hopes that they would allow us to join them in the water.

Timing their breathing cycles, we knew that mom was staying down for nearly 20 minutes between breaths, and so, when she next headed under, we slipped into the water and swam for her “footprint” on the water’s surface, where she disappeared. With all of the recent wind and wave action, the visibility was not ideal, but she was visible below us with the baby tucked under her bright white pectoral fin. A few minutes later, the youngster came up for several breaths and an inspection of the gaggle of humans at the surface. It then went down and came up two more times before mom joined him at the surface and then went down again herself to continue resting. This went on for well over an hour in what would be our best snorkeling opportunity of the trip. It was absolutely amazing to spend this much time watching a baby whale exploring its world!

The skiff with the other half of our passengers on board the liveaboard had come over to join us towards the end of our time in the water. We traded places with them the next time mom came up for air and slowly moved our boat away so they could enjoy their time in the water. As we were debating whether to risk running back for lunch, the trio of whales appeared again around our boat. We had no idea what was drawing them to us as opposed to our sister ship, but the whales proceeded to swim near our boat for the next three hours.

We had begun monitoring breath cycles, preparing for another in-water session when the calf changed course, came in for a closer look and rubbed the underside of our boat. Mom joined her calf at the surface soon after, as they swam around us in tight circles. With no room to get in the water for fear of landing on the whales, we did our best to capture the scene from the surface as the scenario persisted. After several days of weather-related frustration, we were rewarded with a fantastic prolonged interaction and one of my most memorable days on the water with whales.

Topside attractions

The Dominican Republic is a fantastic place to spend a few days before or after your whale-watching adventure. There are hundreds of miles of tropical beaches, picturesque mountains, scenic waterfalls and fascinating cultural experiences.

We spent a day exploring the area around Puerto Plata on the front end of our trip. The day started with a ride on the Caribbean’s only cable car up to the top of Mount Isabel de Torres at 2,600ft (793m). At the summit, there are spectacular views of the city and the Atlantic Ocean beyond as well as walking paths, gardens, lagoons, a cave to explore and a smaller-sized replica of the Christ the Redeemer statue. Numerous tour guides are available to show you around for tip money, or you are welcome to sightsee on your own.

Once back in the city, we stopped at the Del Oro chocolate factory to refuel and learn about the chocolate-making process. Del Oro produces several varieties of chocolate ranging from milk to dark, and all are certified organic from locally sourced cocoa farms.

Reluctantly departing the chocolate factory, we made our way to the famous Malecon, or esplanade, along the waterfront and stopped briefly to photograph the statue of Neptune. This 22ft (7m) bronze statue is mounted on a small island just offshore and serves as the guardian of the harbor.

Continuing north along the Avenida General Gregorio Luperón, our next stop was the Fortress of San Felipe. Built by the Spanish in the 16th century to defend the Dominican Republic from pirates, the fort is now a museum featuring some of the original canons and weaponry. Nearby, a lovely woman was peddling the opportunity to take pictures with her donkey, and while I declined to pose myself, I happily paid her to let me photograph the donkey beside the fortress.

Puerto Plata Central Park was our final destination, along with Umbrella Street and the Paseo de Doña Blanca. The park is more comparable to a quaint town square, with a gazebo in the middle, benches all around and a striking Catholic Cathedral at one end. A short walk from the park, taking you past local shops and colorful Victorian homes, is Umbrella Street. This tourist attraction is designed for photographs and consists of hundreds of rainbow-colored umbrellas suspended over the street. Less than a block away is Paseo de Doña Blanca, an alleyway that has been entirely painted pink. A bronze figure on a bench, where vacationers pose for pictures, and the green plants are the only items that diverge from the color scheme.

Afterthoughts

Our time at the Silver Bank was over far too soon. We returned to the marina after six days off the grid to news of closing borders and cancelled flights from the then impending coronavirus pandemic—a far cry from the awe-inspiring, face-to-face encounters we were experiencing just one day earlier. The opportunity to swim with humpback whales is a once-in-a-lifetime type of adventure that I wish I could repeat every year. I am truly struggling to find the words to describe how extraordinary it is to be in the water with whales. I will find a way to return to the Silver Bank, and I urge you to make the voyage yourself. Bring the whole family—you will thank me later. ■

The author would like to thank Conscious Breath Adventures (consciousbreathadventures.com) for hosting this excursion, the Dominican Republic Ministry of Tourism (godominicanrepublic.com) for their help with flights and logistics, Emotions Playa Dorada (emotionpuertoplata.com) for lodging and the crew of the MV Sea Hunter (underseahunter.com) for taking such good care of us. Thanks also go to Scubapro (scubapro.com) and Blue Abyss Photo (blueabyssphoto.com) for their assistance with underwater dive and photo gear.

Matthew Meier is a professional underwater photographer and travel writer based in San Diego, California. To see more of his work and to order photo prints, please visit:

matthewmeierphoto.com.