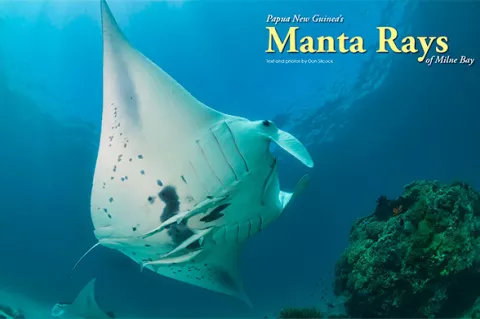

From a distance, there is little to distinguish the small island of Gonu Bara Bara from the myriad of others in this part of southern Milne Bay Province; and few would guess that just off its northern beach is the best place in the whole of Papua New Guinea to see the magnificent reef manta ray—Manta alfredi.

Contributed by

Factfile

Asia correspondent Don Silcock is based in Bali, Indonesia.

He has dived extensively in Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and many other countries in the Indo-Pacific region and his website www.indopacifimages.com is full of information on those locations.

Reef mantas had been known to patrol that beach for many years, but all attempts to try and interact with them were random at best—maybe you would see one or more, maybe you wouldn’t. Then, back in 2002, almost by accident, Craig de Wit discovered why the mantas were there.

Craig is the skipper of the Golden Dawn liveaboard, which had been chartered to search for mantas. He had gone to all the best-known Milne Bay locations but did not find a single one. Finally, in an act of inspired desperation, he responded to the pleas of James, the boat’s engineer, to check out his home island where there were “lots of mantas just off the beach”.

Here is how Craig described finding them:

“I discovered the cleaning station when we went to Gonu Bara Bara, James my engineer kept insisting that there were lots of mantas at his island, so we went in search of them. On arriving, we saw them around the place on the surface, so most of the group went for a snorkel in hopes of getting close to them. I decided to go for a dive along the beach, hoping to get close; and while drifting along in the current, I came across the cleaning station and I guess the rest is now history.”

Craig christened the cleaning station "Giants@Home", and I was fortunate to experience it first-hand just two weeks after that discovery.

Cleaning stations

Cleaning stations are a kind of underwater demilitarized zone where the normal Darwinian survival of the fittest rules of the reef are put on hold while matters of personal hygiene are attended to.

Mantas, like most medium and large underwater creatures, suffer infestation from tiny parasitic crustaceans and have no real way of removing them without some help. That help comes in the shape of small creatures like shrimps, gobies and wrasses who cohabit in specific locations known to both sides as places of mutual benefit—the larger creatures get rid of their unwanted guests and the small ones are allowed access to areas of their guest they would normally never venture, to feed on the rich pickings found there. Interestingly, most of the cleaning creatures have developed stripes, which are believed to identify them as “cleaners” to their potential customers!

Cleaning stations in general are easy to recognize. They tend to be quite common and are great places to watch the interaction between the cleaners and their customers. Typically, when a large fish enters a station, it signals its needs by assuming a trance-like posture, often with its mouth wide open and gills extended outwards so that the cleaners can get access to the most difficult areas. It is quite normal to see the cleaners foraging in the deepest recesses of the fish’s mouth. The usual signal that the truce is over is a shudder from the fish, prompting the cleaners to quickly exit stage left!

Manta cleaning stations

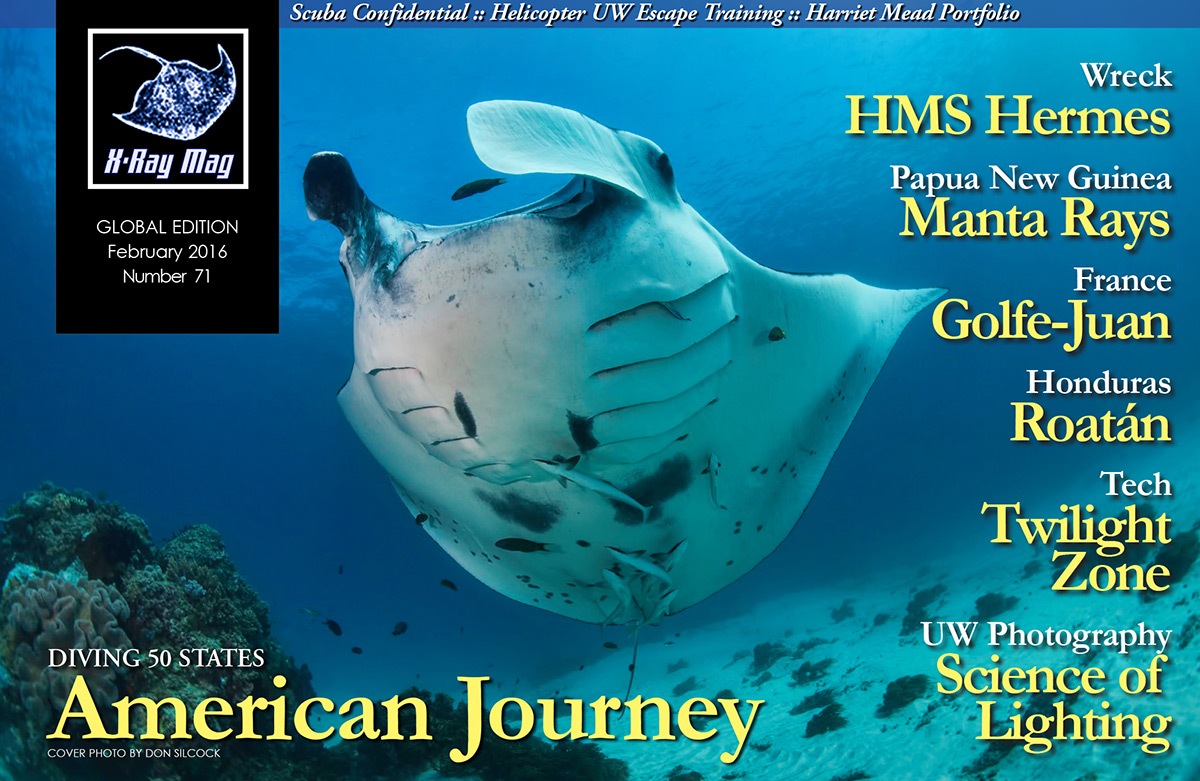

Manta rays are filter-feeding planktivores that use their mouths and modified gill plates to strain plankton and small fishes from the water. They have teeth, which are tiny, peg-like and about the size of a pinhead, but they are not used for feeding. Instead, they are utilized during breeding so that the mating mantas can hold on to each other.

Basically, manta rays are harmless to both man and to the cleaners, but they are nevertheless big animals, with the average wingspan of reef mantas reaching around 5.5m, while the larger oceanic mantas (Manta birostris) getting to at least 7m. They are truly intriguing creatures that are both intelligent and curious, having brains that are significantly larger in proportion to their body size than other fish. Being in their presence is, in my opinion, an absolute joy and cleaning stations are a great way to maximize that interaction time.

Open water encounters with reef mantas are typically fleeting in nature. They will check you out, but that’s usually it, and they move on. Whereas, at a cleaning station, there are more mantas and they stay longer as they take turns being serviced.

Usually, the cleaning station will be close to an area with a strong current that brings the rich plankton which mantas feed on, which explains the early reports of mantas near Gona Bara Bara as close by as the China Strait that connects the Coral Sea to the south with Milne Bay and the Solomon Sea to the north. Giants@Home is a particularly good station as it is shallow at about 9m, so bottom time is not an issue. It is literally just off the beach, which makes it very safe, and water clarity is usually (but not always) pretty good.

But the exceptional thing about its location at Gonu Bara Bara means it can only really be dived from a liveaboard and therefore the total number of divers in the area is the number on the boat and shifts can be organized to minimize the number of divers in the water at any point in time. At other locations, this is rarely the case, and your interaction can often be spoiled by the sheer number of other divers.

Timing at Giants@Home does not seem to really matter, and I have seen mantas on the bommie throughout the day. They are not always there, but very rarely will you dive there and not see at least one (but often many more)!

Manta ray protocol

We have all seen those old images of “intrepid divers” riding on the backs of manta rays by holding on to a couple of resident remoras—so 1970s—but at least the offenders could claim ignorance. Today, we know much more about these wonderful creatures, and they truly are an incredible mix of grace and symmetry, combined with intelligence and curiosity.

Both oceanic and reef mantas are also listed on the IUCN Red List as “Vulnerable”, which means they are likely to become “Endangered” unless the circumstances threatening their survival and reproduction improve. There are many reasons for that status, which are far beyond the scope of this article; but as divers, we are privileged to experience such creatures, and therefore, it is our responsibility to behave properly when we do.

We should never, ever, try to ride a manta like those guys from the 1970s, and we should never chase or harass them in any way! What we should do, and in my personal experience this is by far the best way to get the best interactions, is to position ourselves around the cleaning station so that the mantas have a clear entry and exit. Don’t get too close as you will be in the way, and the mantas will not come in as they appear to feel vulnerable when hovering to be cleaned and are easily spooked.

Once they have made a few passes and gotten used to you, they will often come close to really check you out, which is the best type of encounter, as it is on the manta’s terms and they are in control. Basically, behave and you will be amply rewarded!

So, where is Gonu Bara Bara?

The island is located in southern Milne Bay Province, about 8km to the southeast of the former provincial capital of Samarai Island at the bottom of the China Strait. Roughly 2km wide and 7km long, the China Strait is the passage between the southeastern tip of the Papua New Guinea mainland and the China Strait group of islands. It connects the Coral Sea to the south with Milne Bay and the Solomon Sea to the north and was named by Captain John Moresby, who surveyed the region and claimed the southeastern part of New Guinea for Britain in 1873.

Moresby wrote in his journal that he believed he had found “a new highway between Australia and China”. This was a very big deal at the time as it seemed to provide a way to eliminate the long and dangerous detour sailing ships of the day had to make around the Louisade Archipelago as they made their way north from the eastern coast of Australia to China.

Samarai Island is sadly run-down these days and a shadow of its former glory under the Australian colonial administration, when it was the second largest town in Papua New Guinea after Port Moresby. But its jetty is a treasure trove of critters that make a great alternative to Giants@Home!

How to dive Gonu Bara Bara

The only way to dive at Gonu Bara Bara is from a liveaboard, and there are two that service the area. Top of the list is the MV Chertan, which is owned and operated by Rob van der Loos. Chertan is based in Alotau, the capital of Milne Bay Province and operates year-round in Milne Bay, with regular visits to the China Strait, Samarai Island and, of course, Gonu Bara Bara. Van der Loos has been running dive trips in Milne Bay since 1986 and, simply put, knows the area better than anybody else.

MV Golden Dawn also dives Gonu Bara Bara but it is based from Madang and operates throughout Papua New Guinea depending on the seasons. March, June and October are when the boat visits Milne Bay and, as its skipper Craig de Wit discovered Giants@Home, he clearly owns the bragging rights about the site! ■