— GUE Helps Advance Underwater Archaeology.

This is a “black and blue” story of Panarea III, a 2,200-year-old shipwreck discovered in the Mediterranean just north of Sicily.

Contributed by

The Aeolian Archipelago is a group of seven volcanic islands north of Sicily, Italy. The islands are listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites both for their unique natural environment on land and underwater, and for their oral tradition. The archipelago is named after Aeolus, the mythological Greek god of the wind, and perhaps for good reason. The wind, together with strong currents, unpredictable weather conditions, make the islands one of the most dangerous places for seafarers to navigate. Nonetheless, archaeological evidence dating back seven millenia shows that the archipelago was the center of short and long distance commercial networks.

Mycenaean and Egyptian pottery show the islands were a prehistoric crossroads for people from all over the Mediterranean. Carthaginian, Greek, Roman, Arab and Norman archaeological artefacts show that the islands were crucial stepping-stones for naval battles and used as reference points for navigation through the Messina Strait. This millenary history of conquest and sea supremacy is reinforced by the discovery of dozens of shipwrecks, especially around the islands of Filicudi, Lipari and Panarea. The island of Panarea in particular, which is surrounded by dangerous reefs, surface rocks and deep underwater cliffs, made a perfect spot for deep-water shipwrecks.

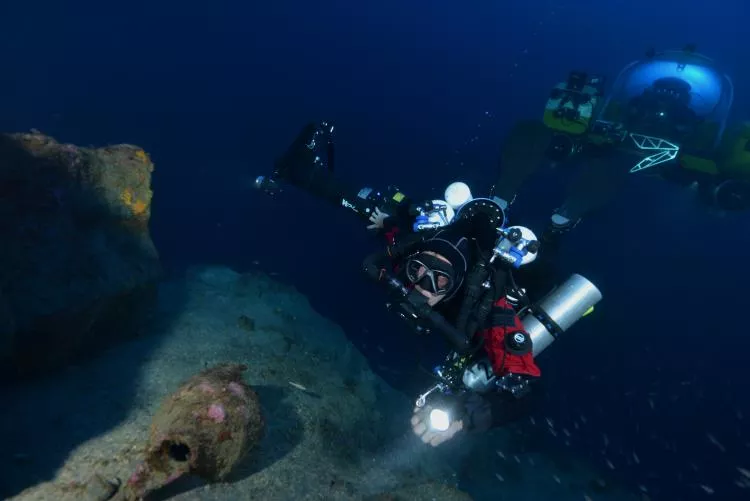

An active volcanic archipelago north of Sicily, lava, obsidian and volcanic ash formed the Aeolian Islands more than 500,000 years ago. The Aeolian Sea, a legendary ocean popular in myths and legends, has an intense shade of blue and a spectacular deepness, taking our team of divers from Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) to depths of 130m in the Mediterranean.

The dream

Explore, dream, discover are the first words that come to mind when recollecting the great adventure our team experienced this summer in the sea of Sicily. It's a dream come true, a dream that began more than 18 years ago when I accidentally came across in my first amphora. This chance find indelibly marked my life by lighting a fire that even today, years later, pushes me to go in search of ancient civilizations. Since that day, when I was still called a boy, my journey as an explorer has evolved. I studied, I listened and I learned that the discovery is only a small part of the research, an inevitable consequence of long, hard work that often takes one away from the sea, into the midst of books and university classrooms.

Today I do not leave anything to chance, and this does not limit my emotion and my desire to discover but rather intensifies it, because it is only then, when you know you have a chance, that you really enjoy and understand the deep meaning of an emotion. Now when I see a wreck of a Roman or Greek ship from more than 2,000 years ago, I can enjoy every single detail of that time capsule, which contains within itself a bit of human history.

Diving into the future

What happened this summer represents the future of underwater archeology, and I say this without presumption, because what we achieved was the result not only of training, but of years invested by participants, in time and resources, to accomplish this feat. We created a team of explorers that for the first time saw action at the same time as researchers and government institutions, by using innovative technologies. The team conducted the study of two ships, Greek and Roman, with the aid of Triton submersibles. Scientists were able to dive with no time limits and study live wrecks—a unique experience that allowed us to collect an amazing array of data and findings. And this was just the beginning. A collaboration between Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) and the Sicilian government is underway to develop an ambitious research project of exploration and study of deep wrecks and water management in the Aeolian Archipelago. The project sets the stage for the beginning of a new era of underwater archaeology.

The ship

Panarea III is not only the material evidence of economic damage due to the loss of very expensive commercial cargo, the shipwreck also reveals new and unexpected commercial networks, which shed light on the social, political and military dynamics at a crucial moment in the history of the Roman Empire and the Mediterranean Sea. In addition, Panarea III reveals the tragedy behind the wreckage, the loss of human lives. This is not an ordinary story of a master and its crew, the unexpected event of a storm and its subsequent shipwreck. The ship's history is a voyage into the most sacred beliefs of a community. The seabed around Panarea was extensively investigated in 2010 by the Soprintendenza del Mare (the Regional Department for Underwater Heritage) directed by Sebastiano Tusa and Martin Gibbs, chief archaeologist of the Aurora Trust foundation. The preliminary geo-acoustic survey detected more than 20 sensitive targets between 50m and 150m. The Panarea III was one of them.

Untouched for 4,200 years

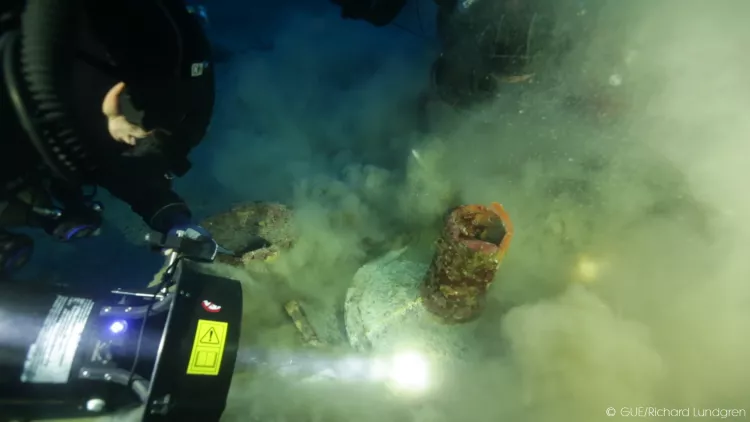

The shipwreck is positioned on a sandy platform at 130m, near an isolated area of volcanic rock. The archaeological site, untouched for more than 4,200 years, appears out of the blue as an oval-shaped assemblage of hundreds of amphorae and other ceramic containers. In addition, the lead part of the wood and lead anchor has been identified on top of the volcanic rock. The remains of the wooden structure of the shipwreck haven’t been found so far; they are most likely resting under the amphorae layer. The cargo was composed of several archaeological artifacts. There are wine amphorae from Campania and Pompeii; Punic amphorae from Cartage or from Sicily, whose contents are still unknown; and there are plates, cups and stone mills.

One of the most interesting finds of the Panarea III shipwreck was a sacrificial altar. The uncertainties and perils at sea, especially in this area of the Mediterranean Sea and the Messina Strait, required the protection of the gods. The altar was used to perform religious ceremonies to protect the voyage, and practices often required sacrifice of small animals such us birds. The spectacular discovery of a rare and expensive object like the sacrificial altar sheds light on the most intimate religious aspect of early navigations. The altar, decorated by sea waves and a mysterious inscription in Greek letters on the base, is currently under investigation by Soprintendenza del Mare and the University of Sydney.

The preliminary investigation suggests that the ship was sailing from southern Italy towards Sicily (or vice versa) approximately during the late 3rd century BC or the beginning of the 2nd century BC. This is an important period in the history of the Mediterranean Sea and the Roman Empire. It is the time of the Second Punic War (218-201 BC) and the battles between the Romans and the Punics for sea supremacy.

The ship could have belonged to an allied town of Campania (Neapolis, Capua, Velia or other Greek-speaking town) supplying the Roman war fleet with food, or maybe it was a supply vessel to the fleet of the Roman general Claudio Marcello who conquered Syracuse in 212 BC, where Archimedes was killed. However, the ship could also have been a merchant ship owned by a wealthy merchant, trading wine or oil from a Greek-speaking town in the area of Naples. The reason that the ship sank was likely due to the dangerous reefs and surface rocks near the island of Panarea. The unpredictable weather conditions and the difficulty of finding protected bays made even the easiest journey through these islands challenging to navigate.

The Panarea III shipwreck is one of the most important discoveries of this decade, not only as an experimental site for the improvement of deep-sea technologies and techniques for scientific archaeological investigation, but also as an important piece of information, which sheds light on a crucial moment in the history of the Roman Empire, and the people of the time. No matter if they where sailors, masters or generals, friends or enemies, through sailing, praying, fighting, they all shared a common sea: the Mediterranean.

Francesco Spaggiari is a professional technical diver and instructor for GUE (Global Underwater Explorers) and Alba Mazza is an Italian archaeologist with the University of Sydney in Australia.

One of the most interesting finds of the Panarea III shipwreck was a sacrificial altar.