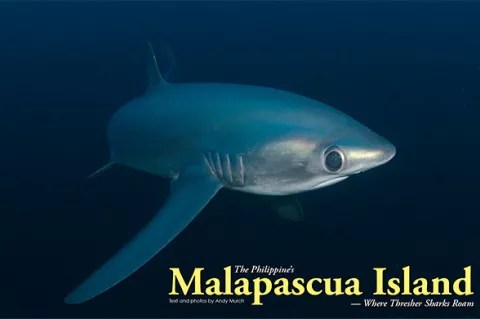

As picture perfect as Malapascua is, in a nation of 7,107 palm tree fringed islands, 2.5km long Malapascua wouldn’t be on anyone’s radar were it not for the thresher sharks that treat the island like a spa. Each morning as the sun peeks over the mountains on distant Cebu, Pelagic threshers rise from the depths to be cleaned by reef fish along a deep ledge known as Monad Shoal.

Contributed by

When my plane touched down in Cebu City in the central Philippines, the ground had barely stopped shaking from a catastrophic earthquake that rocked Bohol and Cebu causing severe property damage and loss of life.

From the media reports that I saw en route, I was expecting total chaos, but Filipinos are used to the occasional quake and no one that I met seemed particularly phased by the tremor that registered 7.2 on the Richter scale. When I reached Malapascua Island, there were no signs at all of earthquake damage, and before long, I completely forgot about the possibility of more violent tectonic shifts.

Monad Shoal

At 6:00am, a dozen Filipino dive boats form a ragged line along the edge of the drop off. I sit quietly in the dawn glow, waiting for the sun to rise high enough to begin the first dive of the day.

The key to close encounters at Monad Shoal is to dive (and shoot) without artificial lights or camera strobes. Threshers have extremely sensitive eyes that are designed for hunting prey in the half-light. Understandably, they do not respond well to flash photography and will bolt at the first sign of a bright light.

Around 6:30am, I join the ranks of bleary-eyed divers slipping below the waves, and descend through clear water to a steep sandy slope at 80ft/24m. When my eyes finally adjust, I see that the lower edge of the slope takes a sharp downturn and plummets past a series of deeper ledges into liquid night. To my right, a coral spur (covered in cleaner fish) juts out from the slope but it is devoid of sharks so we swim on.

As we approach the next cleaning station, Tata—my eagle-eyed divemaster from Thresher Shark Divers (TSD)—gives me a ‘halt’ signal the points insistently along the slope. Straining my eyes in that direction, I drop to the sand and try to look small and nonthreatening.

When the first thresher materializes, there is nothing obviously predatorial about its demeanor. As it snakes past me, the 3m long animal seems confident and nervous in equal measures; an accomplished deepwater hunter forced out of its comfort zone by the need to rid itself of parasites.

Thresher sharks spend much of their lives in the open ocean hunting schooling fish. Over time, they accumulate copepods, sea leaches and various other parasitic organisms that irritate their skin, especially around their vulnerable gill openings and on the trailing edges of their fins. Cleaning stations like the ones at Monad Shoal are a critical part of their daily hygiene regimen.

I continue to hunker down as the thresher approaches the cleaner fish. On its third pass, the shark stalls a few meters in front of me and drops its tail. It’s a clear signal to the cleaners to begin work. Right on cue, a variety of bannerfish, angels and various other parasite eating teliosts swim towards the shark and get busy. The thresher remains motionless for half a minute and then sinks out of view.

Back on board TSD’s roomy banka (a thin, wooden-hulled boat with bamboo outriggers), I relive the encounter and wish that I could slip back in for a second dive. But by 8am, the tropical sun burns down through the water column, and the threshers retreat to the safety of the deep.

Gato Island

In the afternoon, manta rays visit the cleaning stations at Monad Shoal, but I will have to skip that encounter this time around because our banka is headed to Gato Island. The locals say that divers come to Malapascua to see thresher sharks but they leave remembering Gato.

Gato Island is so small that you could easily swim around it on a single dive but no one does because there is simply too much to take in. The island is shaped vaguely like a pyramid and undercut from erosion along the waterline. A small guard’s shack clings to its coral foundations but there is no guard in residence.

Tata explains that ownership of the island is being disputed by two different provinces. With little government funding available, the dive shops on Malapascua pay the guard’s salaries but they can’t police Gato until the dispute is over. In the mean time, the island is under constant siege by illegal dynamite fishermen.

A large cavern runs completely through the island forming a colourful swim-through and a quiet resting place for whitetip reef sharks and whitepotted bamboo sharks. Shimmering bullseyes and silversides swim in dizzying circles in gloomy recesses in the rock and large anemone-toting hermit crabs drag their elaborately adorned shells across the cave floor like society women showing off their outrageous hats.

The shark cave is clearly the headline act at Gato Island but the macro life on the surrounding reef slopes will keep you busy for days. Tata swims along the sand flipping over one heart urchin after another. Each holds a different surprise. On one, a pair of brooks urchin shrimps wave me in for a potential manicure. On another, two coleman shrimps do their best to blend with a purple fire urchin’s spines and on a third, a bold little zebra crab tiptoes over its prickly host in search of scraps. After a second great dive through the cavern I am completely sold on Gato Island and make a mental note to come back here before I leave.

Bad Easter

An hour later, I am back on Malapascua enjoying the sunset from the comfort of the beach bar at Tepanee Beach Resort. The staff—like everyone I meet on the island—are charming and polite but refreshingly relaxed and quick to giggle amongst themselves at the slightest provocation. I could get very comfortable on this slip of land but the first Europeans here felt rather differently.

The name Malapascua was coined by Spanish sailors that spent a long and lonely Christmas holed up on the island. Desperately homesick, the seamen called the Island “Mala Pascua” which literally means “Bad Easter”. Had the aqualung been invented back then, the island might have been named Bella Pascua!

The next morning I join the other shark divers on a deep ledge to watch the threshers slip in and out of visibility. TSD runs a dawn trip to Monad Shoal virtually every day of the year (barring earthquakes and super-typhoons). Sightings hover around 98 percent—an incredible success rate when you consider that there is virtually nowhere else in the world that threshers can be reliably encountered.

Now and then, they even see a few bigeye threshers—a species with extremely large eyes that is usually found in much deeper water.

Dona Marilyn Wreck

Another deep site not far from Malapascua is the wreck of the Dona Marilyn—an inter-island ferry that fell victim to Typhoon Unsang in 1988.

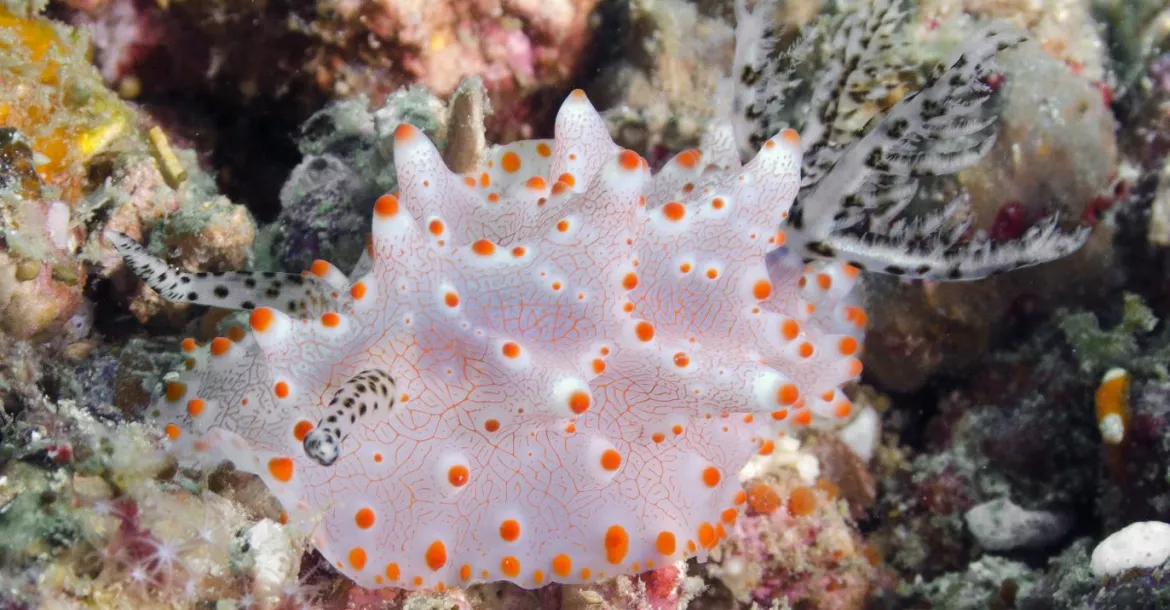

After 25 years underwater, not a lot of the wreck is visible under the shear weight of coral festooning its decks and superstructure. Giant frogfish and broadclub cuttlefish are some of the easily recognizable residents but keen-eyed divers may also stumble upon a variety of nudibranchs, ornate ghost pipefish and the universally popular pygmy seahorses.

Chocolate Island

Later in the week—after our daily dawn thresher encounter—we head to Chocolate Island. I ask three separate divemasters how the island got its name and get three humorous and utterly implausible responses. When we finally submerge, all becomes clear.

The algae and corals that grow in the shallows around Chocolate Island range from dark brown to olive drab. Although healthy, it is not the most visually appealing site, but Tata assures me that it’s a macro wonderland, and after one dive, I couldn’t agree more.

Within a few minutes, I manage to spot dozens of different nudibranchs grazing on the algae and more cleaner shrimp varieties than I have ever seen before.

Macho mandarinfish

With my brain firmly set on macro-mode, I decide to sign up for a night dive to Lighthouse Reef. The seabed here is completely covered by a meter-thick blanket of acropora coral—an excellent habitat for mandarinfish.

Not just beautiful, mandarinfish also make great study subjects for anyone interested in fish behavior. All year long, mandarins indulge in elaborate mating rituals, ballet-like courting displays and dramatic climaxes in which the male and much smaller female throw caution to the wind and swim far above the reef. Then, quivering in what looks like ecstasy, they release a tiny cloud of sperm and eggs into the night. As if coming to their senses, the happy couple then dart back into the safety of the acropora.

Tata swims directly to a nondescript patch of coral where half a dozen mandarinfish are going about the serious business of courting, fighting and mating.

As we look on, two rival males size each other up and then crash head long into each other and bite down on one another’s gill regions. Locked together in this way, the macho mandarins spin in circles until one gains supremacy over the other and chases the inferior suitor away. The winner then struts towards a patiently waiting female like a barroom brawler that has just ‘taken out the trash’. Apparently impressed by the show of bravado, the tiny female stays put while her alpha male swims erratically around her.

I am utterly entranced by the mandarins, but Tata drags me off to shoot a colony of tigertail seahorses a few short kicks away. Although barely 10cm tall, they look enormous compared to the 6mm Denise’s pygmy seahorses that I photographed earlier in the week.

Nearby, a sinister looking spiny devilfish, claws its way across a sand patch to a coral head inhabited by three different species of lionfish and two blue-ringed octopuses. Above the reef a male bigfin reef squid flashes orange then blue and purple. There is clearly too much going on here for me to absorb in just one dive so I add Lighthouse Reef to the rapidly expanding list of sites that I need to revisit.

Super-typhoon Haiyan

By the end of the week my must-dive-again list includes virtually every site that we’ve been to. I clearly have to come back, but shortly after I get home, the headlines are filled with stories about super-typhoon Haiyan.

From the aerial images, it looks as though Cebu Island has been flattened by a giant steamroller. The death toll is almost incomprehensible. For the next few days, I wait patiently for news from Malapascua. The island was directly in the path of the storm and I wonder if it has been wiped off the map forever.

Then the first reports finally come in: most of the locals are safe and the resilient Malapascuans have begun to rebuild their homes. Amazingly, Tata and the other dive masters from TSD are already back in the water analyzing the effects of the enormous waves that accompanied the storm. Like many buildings on the island, their shop sustained some serious damage but not enough to keep them closed for very long.

Reports from underwater are just as promising. As sometimes happens after a big storm, a few things have been moved around, but right now the marine life close to shore is actually better than it was before Haiyan, and because of its depth, the thresher shark dive at Monad Shoal was completely unaffected. So by the time I get back to Malapascua next year, it looks like I will be able to tick off all those must-dive-again sites from my list and then hopefully add a few more. ■

Andy Murch is a photojournalist and outspoken conservationist specializing in images of sharks and rays. Bigfishexpeditions.com