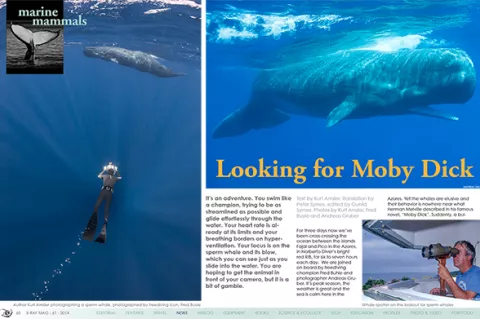

It’s an adventure. You swim like a champion, trying to be as streamlined as possible and glide effortlessly through the water. Your heart rate is already at its limits and your breathing borders on hyperventilation. Your focus is on the sperm whale and its blow, which you can see just as you slide into the water. You are hoping to get the animal in front of your camera, but it is a bit of gamble.

Contributed by

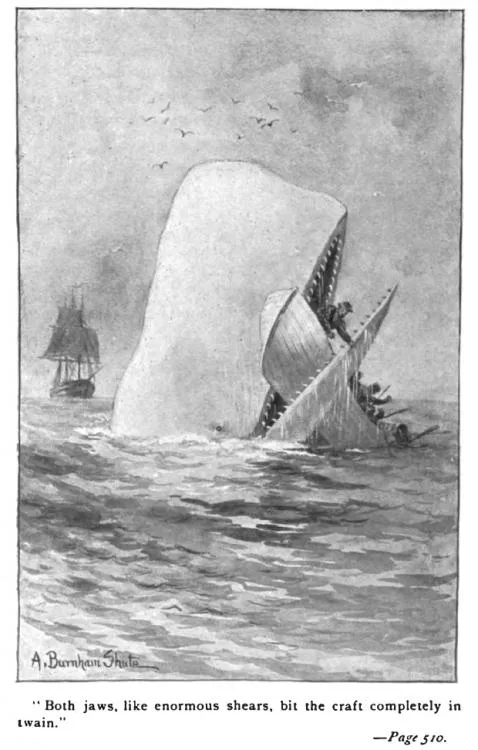

Yet the whales are elusive and their behavior is nowhere near what Herman Melville described in his famous novel, “Moby Dick”. Suddenly, a bulbous head sticks high out of the water. With flippers slapping the water, the sperm whale heads straight for us in order to ram us.

“Baleya Baleya!” Ahead to starboard, Norberto cries out. He’s both excited and visibly relieved after having searched for the whales for over three hours. What now ensues is a carefully choreographed sequence of maneuvers that has been practiced countless times but still feels tense. The animal may stay on the surface, but in most cases it dives, and you have to start all over.

I perform a superfast last check of my camera equipment and I am all set. Norberto has years of experience in dealing with marine mammals and knows exactly how to proceed in order not to scare away a whale.

At a distance of around 150 meters, he throttles back and keeps pace with the animal, waiting to see whether the 4m (12ft) long female sperm whale remains calm in our presence. Next, he very carefully closes the distance to about 100 meters while maneuvering into a position a little bit in front of the whale.

It is now or never

“Go, go!” With a last glance at the animal to fix its position, we slide into the water. During this 100-meter sprint towards the whale, every second counts. The angle of the light rays steaming down from the sky serve as a reference point in order to stay on course, with our eyes searching ahead into the blue, trying to catch the outline of a whale.

We are about to find out if we got our hopes up for nothing or whether the whales have, as so often before, dived and slipped away out of sight. I am just about to give up when I finally see him. First vaguely, then more clearly, as it swims, to my astonishment and delight, in a 45 degree angle towards me. Crunch time! Now, it is about not screwing up this golden opportunity.

I focus, bring my galloping breathing under control and catch the right moment to dive. Not only is going down a better camera position, but it also allows to me to forestall any changes of direction and dive along with the whale. Going vertically down head first is the hardest part. If you lose sight of the animal, it is gone.

As I level off, I find myself at about 10m, and I start following the action through the viewfinder. I gently keep triggering the shutter and seconds turn into minutes until the whale finally breaks off and dives, with no chance for us to follow it.

Once I am back at the surface, I try to catch my breath, and the words of freediving champion Fred Buyle comes to mind: “Don’t feel bad, Kurt. They always win!”

Moby Dick

This novel, which is now a literary classic, was a commercial failure when it was first published in London and New York in 1851. And it was only a long time after the author’s death in 1891, when the book was well out of print, that its reputation rose during the 20th century. The first translations into German appeared in 1927.

One of the most distinctive features of the book is the variety of genres that appear. Melville uses a wide range of styles and literary devices to blend the complexity of the fascinating whale, the ethical ambivalence of hunting these magnificent creatures, and the incredibly diverse appreciation of whales and whaling across the world’s cultures.

Moby Dick is based on Melville’s actual experience on a whaling vessel. He described the whale in either florid mythical terms or in the language of the early marine biologists. Some passages are written using the old jargon of the New England Quakers, others like the preaching tales of old bible translations. He moved with ease from the language of a sailor to the dry prose of expedition reports. He described exotic cultures in the style of the racist adventure literature of the day in order to fit right into the prevailing tone of the establishment.

The sperm whale

(Physeter macrocephalus or Physeter catodon). Even at birth, the sperm whale breaks all records for toothed whales; A baby whale can weigh over a ton. But it is their diving capabilities that really stand out. One specimen which was equipped with sensors and transmitters dove to a depth of 2,270 meters.

The bulls can reach a length of 18 meters and a weight of 40 tons. As such, they are the biggest predators on the planet. The body is stocky and the characteristic bulbous head can account for a third of the total length. The dorsal fin is small and it has short and stubby pectoral fins. The tail fluke is shaped like two equilateral triangles and is slightly rounded at the top and deeply notched in the middle.

The one blowhole is located at the upper tip of the head. The huge head of a sperm whale is to a large part filled with an oily substance, also called spermaceti. It is believed that the head also serves as an “acoustic lens” focusing sound waves sent out during echo location. Emitting high-frequency clicking sounds the animals scan the surrounding environment and are able to image a large area.

The sperm whale is found in all oceans. It is most common in the tropics and subtropics, but is also found in colder seas. In 2004, a sperm whale was even spotted in the Baltic Sea for the first time.

On average, the males dive deeper than females. The duration of a dive can be from 20 to 120 minutes. How it’s possible for sperm whales to hold their breath for such extended periods of time has not yet been fully explained. It is known that they are able to restrict and slow down their metabolism to a minimum while diving, during which time, blood is directed only towards essential organs such as the heart, brain and spinal cord.

In addition, sperm whales have 50 percent more hemoglobin in their blood than humans do, enabling them to store large supplies of oxygen. Sperm whales’ preferred prey is squid, and parts of the fabled giant squid has regularly been found in their stomachs.

Females form social networks with their young and live in groups of about 15 to 20 animals. Sexually mature males then leave and later form associations or groups with older males but travel alone.

Whaling in the Azores

Whalers from America and later, England, brought whaling to the Azores. Whaling was not actually performed in these waters, but the islands were used for provisions and supplementing crews with young, brave and energetic men from the archipelago. In time, the Azoreans took up whaling themselves and established their own whaling stations along the coast.

On the islands, high above sea level, lookouts were established from whence the so-called “Vigias da Baleia” or “looking for whales” could be conducted using binoculars overlooking the ocean. These observers were the most important men in the whaling, because only their eyes could direct the whalers to their targets. When a whale was spotted, at first smoke signals were used, later rockets were shot into the sky until finally radios were used.

The whalers were fishermen, craftsmen or farmers who dropped what they were doing once a whale was sighted. The cry “Baleia! Baleia!” signaled the men in the fields to leave what they were doing and head as fast as possible to the harbor where their boats were constantly ready to sail.

Early on, they went out in long slender rowing boats called “Canoas” sometimes assisted by sails. In the second half of the 20th century, motor boats were used to power the whaling boats, which had a crew of up to seven out at sea.

If the whale surfaced, the crew had to row over to it as quickly as possible. The “Arpoador” hurled the harpoon by hand into the flanks of the giant. Hit by the harpoon, the whales would flee, in most cases, by diving deep. In such cases, the up to one kilometer-long rope wound out rapidly. This was the most dangerous part of the hunt, because if anyone got snagged by the rope reeling out, he would be pulled under.

Many whalers lost their lives in the hunt. Whole boats could be pulled to the depths if the rope was not cut before the end was reached.

In 1984, whaling in the Azores came to an end, making room for a new lucrative business; nowadays, the only hunting done is with photo and video cameras and not with harpoons. Many of the old observation posts are also in use again this time by whale watching companies taking tourists and divers out. Even some of the old “Vigias” are now back in action many years after the ban on whaling came into place; they now assist the tourists with their good eyes, which still provide an important service.

Freediving with whales

I have been so fortunate to dive with some of the largest whales of the oceans. The first encounter I had was in 1990 diving with resident pilot whales. At that time, there were virtually no commercial whale watching or snorkelling tours and no regulations. We could spend days with the animals without being disturbed. In Polynesia, I have been freediving with humpback whales, which bring their young to the warm waters there.

Another unforgettable experience

Experiencing these giants was simply huge. Appreciating that humpbacks expend their energy reserves during the long trek from the Arctic, I cannot let go of the idea of also diving with these creatures in the Arctic. But the most impressive of all cetaceans, is the sperm whale which “Moby Dick” once made world-famous! He is the beast of superlatives and the largest predator that ever lived on our planet. He can hold his breath for two hours, dive to 3,000 meters and eats a ton of squid per day!

The Azores, which are now my second home, is probably the best place to get a camera in front of these giants. There are places, Mauritius and Dominica, where the access is much easier, but the challenge and adventure cannot compare. Despite being hunted to the brink of extinction by humans, the animals show absolutely no aggression when you are with them in the water. Catch them on a good day, the sperm whales can also be quite curious and try to communicate with their extremely well-developed cognitive abilities—our problem is to figure out how to answer. ■

For more information, please

visit Kurt Amsler’s website at:

www.photosub.com