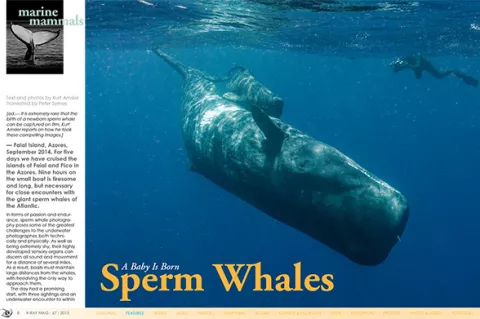

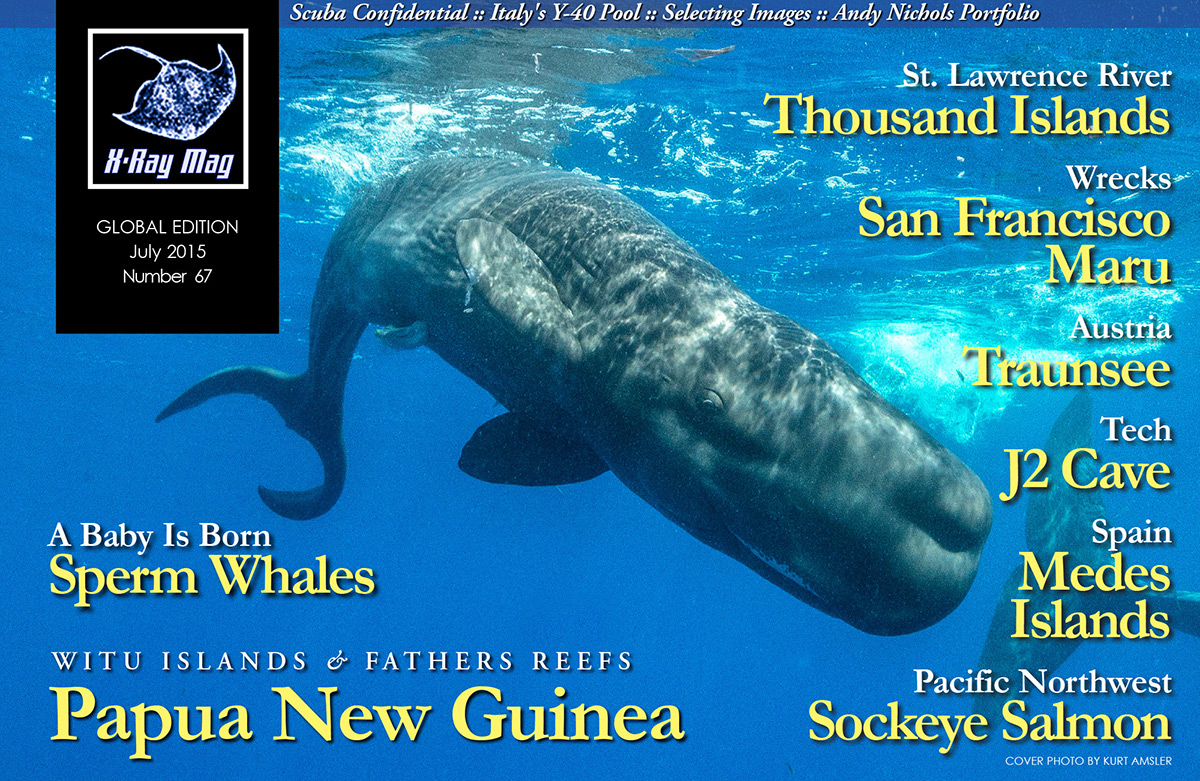

— Faial Island, Azores, September 2014. For five days, we have cruised the islands of Faial and Pico in the Azores. Nine hours on the small boat is tiresome and long, but necessary for close encounters with the giant sperm whales of the Atlantic.

Contributed by

In terms of passion and endurance, sperm whale photography poses some of the greatest challenges to the underwater photographer, both technically and physically. As well as being extremely shy, their highly developed sensory organs can discern all sound and movement for a distance of several miles. As a result, boats must maintain large distances from the whales, with freediving the only way to approach them.

The day had a promising start, with three sightings and an underwater encounter to within a distance of 50 metres. From a small boat like ours, it is not possible to see the ‘blow“ and the back of whales at the surface. Therefore, we work with so-called “Vigias Baleia“, men positioned in hillside observation towers that are remnants from a time when commercial whaling existed in the Azores.

Scanning the surface with powerful binoculars, they communicate the position of the animals. Suddenly, the radio is crackling again. From the boat driver’s reaction, it must be a very good message. A group of about six animals has been spotted approximately one nautical mile to the south/southwest.

A unique dive with sperm whales

Courtesy of our boat’s twin 150 HP motors, we reach the spot quickly and see our quarry immediately. The pod moves very slowly while turning circles, a decidedly strange behaviour. Careful not to scare them away, we cut the motors and maintain safe distance of 100 metres. With a last look at the pod’s position, I gently slide into the water.

For the first 60 metres, I go as fast as possible, scanning the blue to catch a glimpse of the animals. However, there is nothing but a big murky cloud. I then realize it is blood, which appears greenish underwater by the loss of red spectrum.

This could explain the pod’s strange behaviour—a wounded animal watched over by the others! As the whales’ communication sounds intensify, I can see the group about 18 metres in front of me, just below the surface and huddled together. With the sun directly in front of me, it is very difficult to see exactly what is going on.

I then descend to 15 metres and carefully pass beneath the whales. Now they are clearly distinguished from the background and I realize what is happening; this is not a wounded animal but a mother giving birth!

Parts of skin and the placenta are floating around and I can see the baby, which had left the womb just a few seconds earlier. It is still immobile and supported by five midwives to the surface for its first breath. The mother, still weak, is watching it from below.

Baby’s first moments

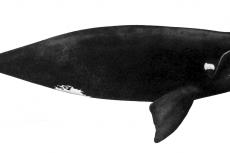

Newborn whales are not able to swim within the first minutes and would drown without assistance. Therefore, always other females are in attendance as midwives. By this time, the mother has arrived to support her newborn, which is easily 2.8 metres in length.

With every passing minute the baby is increasingly mobile and able to swim independently over short distances. I can also hear his communication, which has a higher pitch than the others—the voice of a child.

Protective mother

In order not to disturb the animals, I move very carefully and maintain a distance of about 10 metres. Up to this point, the whales have not taken any notice of my presence, but now it seems the mother wants to identify the stranger in their midst.

Quietly but directly, the nine-metre long giant turns in my direction and swims right up to me. Her massive head is getting bigger and bigger as the water displacement pushes me away. Water churns around me and the exhalation noise thunders in my ears! I see the eye looking at me and I feel absolutely no aggression. I am thoroughly overwhelmed by the experience!

Whales communicate perpetually, with their sounds being heard by others over great distances. As the birth was communicated, more and more animals arrive for the event. The giants surround me and I am fully accepted!

Presenting a newborn

The mother swims to other groups to present her child. She does the same to me, stopping and allowing the baby swim towards me—incredible! After about 20 minutes, the baby becomes stronger and moves faster. From time to time, it wants to venture away on its own, which the mother does not like at all. With her immense toothy mouth, she brings the runaway back to surface.

Sperm whales feed on giant squid, which they hunt to depths of 2,000 metres. More than 40 conical teeth, each reaching a length 20cm, sit in the lower jaw.

As the event comes to its conclusion, more and more whales disappear into the blue of the Atlantic. The mother then descends with her child to their realm below.

Afterthoughts

In my 45 years of underwater photography, I have documented many spectacular and unique situations. However, this experience was the most powerful of all! More importantly for me is the hope that these unique images will spread awareness and encourage people to support the protection of these intelligent and endangered marine mammals in any way they can. It is shameful that thousands of whales are still hunted annually, victims of human senselessness, greed and under the guise of outdated traditions. ■

Kurt Amsler’s dives with the sperm whales were authorized by the government of the Azores and every precaution was taken not to disturb the animals.

For more information, visit Kurt Amsler’s website at: www.photosub.com.