— On Foot in Raja Ampat

Contributed by

Factfile

Don Silcock is a Bali-based underwater photographer and writer whose principal focus is the diving and cultures of the Indo-Pacific region.

His images, articles and extensive location guides can be found online on his website: Indopacificimages.com.

Located in the far east of the vast Indonesian archipelago of almost 18,000 islands, Raja Ampat has truly captured the imagination of the global diving community, with tales of the underwater adventures that abound there.

It is one of the hottest locations, and at the start of the main dive season in mid-October, liveaboard dive boats start to arrive in Sorong in droves. In Sorong—the main town of the Bird’s Head peninsular—just ten years ago, you could count the number of those boats on the fingers of both hands and still have a few digits left. But these days, there at least 50 boats operating during the season, and Sorong harbor has become a very busy place!

So popular has Raja Ampat become that there are now boats catering for all levels of diving travelers, from super luxury vessels for which you don’t even need to bring any dive gear (they have it all on board for your convenience) to backpacker boats that still get you to the same places, albeit in a slightly different, more economical style.

I have been to Raja Ampat many times over the years, but always on a liveaboard, and am very much of the opinion that it is the only way to get to all the main locations, which indeed it is, given the large area that Raja Ampat covers. But what if you don’t want to, or can’t afford to do a liveaboard? Is there an alternative?

On my trips to Raja Ampat, I have seen a significant number of land-based resorts being established offering “local” diving, following the model first established by Max Ammer, the original pioneer of diving in Raja Ampat, with his first dive camp on Kri Island in the Dampier Strait. I was curious to see how land-based diving would compare with the liveaboard-based experience I have had, so when I received an invite from Wicked Diving to try their new dive resort in the Dampier Strait, I decided to accept and see the reality for myself.

Diving Raja Ampat — Some basic geography

Raja Ampat, or the “Four Kings”, refers to the four main islands of Waigeo, Salawati, Batanta and Misool, but there are some 1,500 smaller islands in Raja Ampat that make up the total land area of about 15,000 sq km and a total area of around 40,000 sq km.

You get the picture—it’s a really big place. And to see the incredible biodiversity of the area, you need at least a two-week liveaboard trip to get to the main areas.

Most liveaboards start their trips with a couple of days in the Dampier Strait, which separates the “mainland” and the islands of Batanta and Sulawati in the south from the large northern island of Waigeo. Then they usually head south to the Misool area and the fabulous dive sites on the Sagof-Daram and Southern Archipelagos in the southeast, often breaking their journey to dive the sheltered black sand critter sites on the southwest coast of Batanta.

The Dampier Strait — Where it all began!

Named after William Dampier, the English explorer-adventurer who first charted the area in the 17th century, the Dampier Strait is where the Indonesian Throughflow first touches land in Indonesia. The Throughflow is the largest movement of water in the world and is the basic reason for the incredible biodiversity of Raja Ampat.

When those huge volumes of water enter the Dampier Strait, they are funneled through its shallower depths producing some very strong currents that surge around the seamounts and reefs of the Strait. The cycle of life those currents create is staggering, and it was the diving in the Dampier Strait that first brought the liveaboards to Raja Ampat—all history now—but it is true that the sites in the Strait tend to get overshadowed by the ones in the south. So the offer to do some intensive diving in the Dampier Strait was too good to decline and I set off for 10 days in Raja Ampat—by foot!

Getting there

I have to admit, it was all quite a bit different from doing Raja Ampat by liveaboard in which the hardest part is getting to Sorong, and from there, all the logistics are typically organized for you, and you are whisked away from the airport, either straight onto the boat, or to one of the numerous modern hotels that have sprung up in the last few years.

You can also arrange for the land-based resorts to pick you up, but it’s not cheap because of the distances involved. By far, the most cost-effective way is to get the ferry over to Waisai on the island of Waigeo. The ferries operate daily and are quite efficient, but you have to get down to the terminal to buy your ticket and then get all your gear out to the ferry, which in my case, was quite a task, with full sets of diving and underwater photography equipment—a problem that was quickly resolved by hiring one of the numerous porters who hang out at the terminal.

Although it is the capitol of Raja Ampat, regency Wasai is a fraction of the size of Sorong, but it’s a neat and friendly enough place, and Max from Wicked Diving gave me the full 10-minute tour of the town when I arrived on the ferry!

About the dive operator

Co-founded and run by Bali-based American expat Paul Landgraver, Wicked Diving is an interesting business that focuses on the younger end of the diving spectrum and differentiates itself in a crowded market with its strong focus on what it calls “ethical diving”. I was frankly more than a little bit dubious about it, initially, as it sounded like a cute marketing tactic, but it does seem they don’t just talk the talk—they walk the walk too! A key element is their “2% policy” whereby 2% of their total revenue is used to help the local communities and ecosystems where they operate. Examples of this include their support of the Baan San Fan Orphanage north of Phuket in Thailand, as well as the dive guide internship program for villagers in Komodo, Indonesia. They also practice “low impact” diving, which they define as leaving as little evidence behind that they were even there, which is a big topic covering everything from rechargeable batteries to organic bio-degradable shampoos.

Diving logistics

Frankly, this was the element of diving the Dampier Strait by foot that I was most concerned about, because the currents generated by the Indonesian Throughflow are complex, and at their strongest, a force of nature not to be taken lightly!

Diving the Dampier Strait from a well-operated liveaboard typically involves it acting as the mother-ship and inflatables acting as tenders to get the divers in the right position to enter the water and then provide surface cover in case something happens. Two tenders are required as a minimum, so that one is always providing surface cover if the other one is picking up divers or returning them to the mother ship.

I was really pleased (and just little bit relieved) to see that the dive staff, led by the highly-skilled Jess Nuttridge from New Zealand, had worked out how to dive the Dampier Strait dive sites using a single small, but maneuverable, mother ship. Jess achieved this by always getting in the water before we did, to survey the currents and position the mother ship in the right location—it worked, and I was impressed.

What will you see?

So, you are finally in Raja Ampat and all set to get into its famous waters. Now, what are you going to see? Well, the correct technical answer is “a lot” because the rich currents of the Indonesian Throughflow produce some of the most stunning biodiversity in the world.

The diving can be segregated in to four main flavors: the incredible sea-mounts in the actual strait, the flanking reefs where the rich currents touch the main islands of the strait, the jetties on the islands that are ecosystems in themselves, and the world-famous manta ray cleaning station at Manta Sandy. Let me give you a little taste of those flavors to whet your appetite…

Seamounts. Think of these as small underwater mountains that rise up from the seafloor of the Dampier Strait and the eastern sides of which face right into the Indonesian Throughflow. Diving the sea-mounts requires a specific technique, usually referred to as a “negative entry”, whereby you enter the water at least 50m up-current from the eastern side and get down straightway.

If you dilly-dally about on the surface, the current will sweep you past the site, as its velocity increases exponentially the closer it gets to the seamount. The key to safely diving the seamounts and being able to enjoy the experience is to find the “split point”—this is where the current hits the center of the eastern side, but which varies on the state of the tide.

On the split point, the current is negligible, and you can relax and enjoy the show because out in front of you in the current, you will see nature at it’s very best as the pelagics hunt, swoop, dodge and weave! If you stray north or south from the split point, or start to ascend, you will feel the current ramp up. And if you continue, it becomes impossible to swim against, and you will have to surrender and (literally) go with the flow.

The trick is to time your dive and air consumption so that you can sweep past the flank of the seamount and get to the calm western side to safely conduct your safety stop and regain your composure before surfacing. Never dive a seamount without your safety sausage—it could save your life if you screw up and get swept out into the Dampier Strait!

Flanking reefs. There are many of these in the Dampier Strait—some are great, most are good and some less so. The best, in my opinion, is Cape Kri, at the eastern tip of Kri Island. This is basically where diving began in Raja Ampat, with Max Ammer and his early beach-camps. It’s also where the renowned American-born Australian ichthyologist, Gerry Allen, counted a world record number of 374 different species in a single location in April 2012.

The biodiversity at Cape Kri is absolutely stunning to see, and it seems that everywhere you look, there is something incredible to see—from schooling pelagics out in the blue to grey reef sharks patrolling the reef, with superb coral bommies all the way down the flank. To observe all that biodiversity in one location makes you realize just what an amazing place Raja Ampat is!

Jetties. There are many jetties in the Dampier Strait. There has to be, because boats are the principle form of transport. Quite why they attract so much marine life is not clear to me, but they are almost always great places to dive and explore. They also provide great photo-opportunities with the village kids, who always seem to gravitate there after school and use them as diving platforms.

Once the kids know that you want them to swim down and pose for you, they do so like playful seals trying to outdo each other by “hamming it up” for the camera, which makes for a lot of fun all round! The kids love nothing more than seeing the images taken of them, and on one trip, we even got some prints done and got the boat to deliver them the next time they visited.

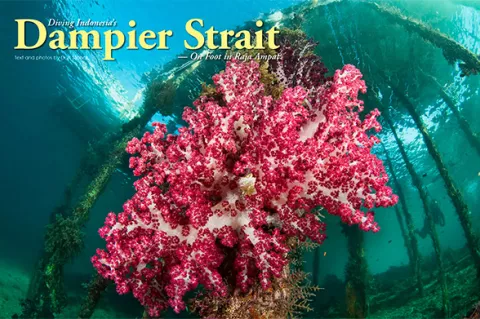

The most well-known jetty is at the island of Arborek, at the western end of the Dampier Strait, which is famed for the soft coral growth on its pylons and the schools of fish that live under the jetty. But there are several others that deserve a visit, and a couple of my personal favorites include Sayandarek, where the schooling batfish offer some great wide-angle photo-opportunities, and Szonic Jetty where there are many macro encounters if you take the time to search in the sea-grass that abounds there.

Manta Sandy. This site is a cleaning station, where reef mantas congregate in the morning to have their parasites removed, and is probably the single most reliable place to see these wonderful creatures in all of Raja Ampat. It is located at the western end of the Dampier Strait, not far from Airborek Island, and is on the southern side of the large reef that separates it from the much larger Mansuar Island.

I like to think of cleaning stations as the underwater equivalents of demilitarized zones where the normal dog-eat-dog (should that be fish-eat-fish?) rules of the reef are put on hold, while small cleaner fish are allowed to feast on the parasites that infest larger creatures.

At Manta Sandy the DMZ is a group of small bommies in a channel that runs parallel to the reef. Mantas start to gather there from around 8:00 most mornings—taking turns to hover above the rocks while the cleaner fish swim up in pursuit of the parasites.

The site is very popular, and to ensure the presence of so many divers does not drive away the mantas, a strict demarcation code is in place using a line of rocks laid out in about 16m of water. The rocks are close enough to the bommies to allow divers to observe and photograph the mantas, but far enough away to allow them to be cleaned in relative peace. The thing to do is get yourself in position somewhere along the demarcation line where you can comfortably hold on against the currents and then wait.

The site is fairly shallow and so bottom time is not an issue. As the mantas complete their cleaning rituals, they often come and check out the waiting divers, with some upfront and personal interactions.

So is walking a real option?

My honest opinion is yes, it is, and I think that land-based diving in the Dampier Strait has some distinct advantages in that most of the best sites are relatively close together, so getting to them is not a big deal.

Not having the option to dive the reefs down south in Misool, or some of the other equally great sites that Raja Ampat has to offer, means that you are focused on the sites in the Dampier Strait and many of these are truly world-class, but tend to be skimped upon when diving from a liveaboard.

Land-based diving is also typically cheaper than a liveaboard. Plus, you can select the number of diving days that best suits both your schedule and your budget, rather than be held to the fixed duration of most liveaboards. But if you are going to travel all the way to Sorong to dive the Dampier Strait, do yourself a favor and allow enough time there to do it justice, which I would say is a minimum of six days in the water. ■