Sighting a sea turtle on a dive is always a pleasure. However, few know much about what they are like as animals. Being reptiles, it is assumed that they are essentially on automatic—emotionless and thoughtless. But we changed our minds about that when Merlin came. Ila France Porcher relays the tale of rehabilitating a sick sea turtle in Tahiti, at a time when turtles were often hunted for food.

Contributed by

(If you have read Part One in the Issue 113 PDF, please scroll down to the subheading "Part Two: Foraging and taking flight.")

Part One

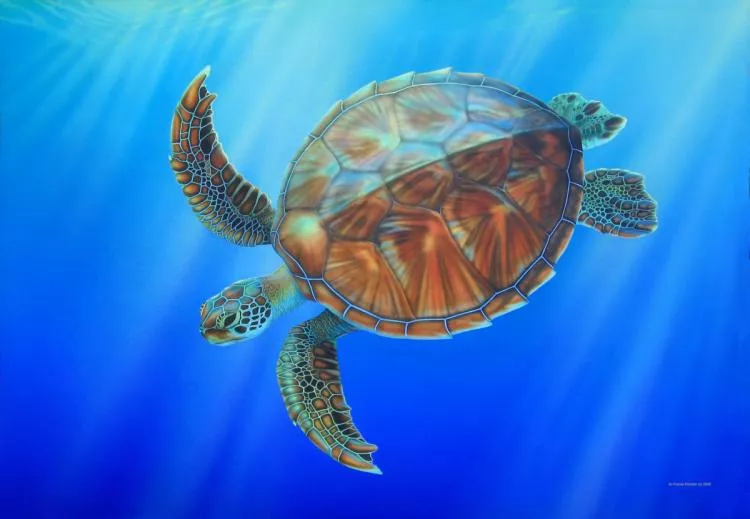

Merlin came at sunrise, carried on the waves, a green sea turtle afloat and flailing. I carried him in from the sea and installed him in a deep blue basin where he steadily strove to dive down. But he could not. He floated high in the water so that all but the edge of his shell was above the surface and his respiratory rate was very fast—he took about one breath per minute. He was a rich amber colour with intricately patterned wings, head, and hind fins. His shell was nearly round and thirty-nine centimetres in length. Suspecting that his buoyancy was the result of a respiratory infection, I began injections of antibiotics immediately.

He was calmer the next morning but still spent much of his time trying to submerge. Whenever I put my hand near him, he moved his head to press against it.

Merlin’s condition declined until he lay immobile on the surface. He did not swallow the small fish and vegetables I put into his mouth; I had to push them down his throat. His flesh lost its vitality, and his respiratory rate slowed to a breath every fifteen or twenty minutes. When taken daily to swim, there was no muscle response. His head and fins hung motionless, and his mouth was slack. When his course of antibiotics was finished, mucous seeped from him and strands of it filled the water. I changed it often.

Weeks turned to months as he waited at death’s door, and my husband, Franck, and I gave up hope that he would live. It seemed unbelievable that he could go on so long in such a lifeless state.

Return to life

But there came a day when he began to move weakly. As he slowly returned to the world of the living, he began to hold his head up enough that his eyes were above the water’s surface so he could watch us moving around the house.

We encouraged him to swim in the sea, hoping that exercise would help to clear his lungs, and put him in an inflatable pool on the deck. He circled it slowly, looking around. I held a shellfish under the surface and he waved one wing back and forth until he drifted near. Then he lunged upon it. But though he had it between his jaws, he was unable to manipulate it into his mouth. Even when I steadied him, he could not eat, in spite of multiple manoeuvres and thrashing about. He became so frustrated with his difficulties that I put it into his mouth as I had done when he was very sick. After that, he always relaxed his jaw so I could put his food in his mouth, and never did he bite.

Nourishment

Now that he was recovering, he required a surprising amount of food, and keeping him supplied with shellfish was impossible. I began giving him tiny fish donated by a fisherman and took him daily looking for seaweeds that he might like. Once, as we drifted along, I opened his mouth to check that he had no rotting food inside. Looking right at me, he opened his mouth so that I could see in all the way to his stomach, and powerfully expelled a cloud of rotting fish into my face. I took it as a statement and never gave him those fish again.

Instead, I collected snails and other items from the rocks along the shore for him, and took frequent excursions to the reef to bring back quantities of a seaweed beloved by sea turtles. Occasionally, there were turtles grazing there and some were very large, more than a metre in length. Their shells were elongated compared with Merlin’s, which was nearly as round as a pie; clearly, he was a juvenile. His pool was decorated with a variety of sea plants in an effort to discover more foods that he liked. He was still unable to dive, but floated lower in the water with his shell now half-submerged.

Craving attention

He wanted continuous attention and came to me whenever he saw me. Floating in his pool, he gazed up at the trees arching over him, the mountains and sky, and he watched anyone in view while scenting the air. It was a strange phenomenon, a marine reptile so exquisitely adapted to marine life, whose interests suddenly lay in the world above the surface.

I spent hours drawing the patterns of his scales, and for that, I needed a side view. But he would swim towards me and rest his chin on the edge of the pool. I would stroke him, and give him a shellfish, but when I tried again for the side view, he turned with me. He wanted as much attention as he could get, and day after day I spent more time fussing with him than I did drawing him. Usually, while he was occupied with his bit of food, I could draw him uninterrupted for a few moments, but not for long.

Once, my patience was wearing thin, and instead of getting him more shellfish, I gave him some lettuce that happened to be handy. He shook his head and spat it out, then violently smacked his flippers on the surface several times and turned his back on me. Now, try as I might to get the side view, he kept his tail end turned exactly in my direction! It took him fifteen minutes to get over his fit of pique and drift back towards me again.

This unexpected incident suggested that he had ideas and preferences that very much mattered to him!

Trouble

One day, a stranger came by, saw Merlin, and went uninvited to look at him. Two days later, he returned with another man, who claimed to be a government authority on sea turtles and demanded to see the one I had in custody. As we walked to Merlin’s pool, I told the man his history, but he stated coldly that I had no right to keep him, snatched Merlin from the water, and roughly examined him. I said that my husband (who, I mentioned, spoke French without an accent), had called every branch of the government to ask for advice and help, but had failed to find anyone who could advise us about his care. (And being in a remote location, there was no access to the internet at the time, through which information such as this could be found). So, we had been obliged to treat the stricken reptile on our own.

Then, I asked him what a healthy turtle’s respiratory rate should be, but he ignored the question. Anxious to learn, since he was the first sea turtle expert I had met, I asked again. He said it depended.

“But when a healthy animal is at rest,” I asked, “how often does it breathe?” Again, he replied vaguely, and I realised that he did not know! He told me brusquely that the turtle would be transferred to a government holding facility at once and said that someone would come by later that day to pick him up.

After he had gone, I carried Merlin into the house and laid him on cushions, while filling his blue basin with seawater in a dark room at the back of the house. Then I locked the doors, pulled all the curtains, and sat down beside him with my latest drawing propped in front of me.

Merlin threw a violent fit to find himself back in his basin in the house, and splashed so much sea water around that it took the next twenty minutes to clean it up. Finally, he calmed downn as I sat stroking him, alert and listening. I was terrified. Not being French, I was uncertain if I had any human rights in the country, and was afraid that if I was caught breaking any laws, such as the one governing the touching of sea turtles, I could be deported.

On the other hand, while the rest of the world was working to save sea turtles from extinction, in Tahiti, the law tolerated people eating just as many as they wanted. They were very religious and believed that God had put sea turtles in the sea just for them to eat―even the very last one! But it was wrong to try to save one from death. I waited, trembling with anxiety, systematically drawing. The day darkened, and eventually I just looked out across the grey sea, comforting Merlin. When I was beginning to think that I had overreacted, a vehicle drove onto the lawn. I could hear it but dared not look.

There was a loud knock on the door, and in the subsequent silence, a man began yelling, “Allô!” Listening intently, I followed his progress around the house, imagining making a plea to a judge on Merlin’s behalf. Only I knew his needs and it would endanger him, after all he had been through, to put him into a strange facility. Surely, I was in the right... Footsteps approached along the deck. Merlin’s pool, decorated with seaweeds, sponges, and the seashell he liked to clutch, was empty, and the man paused there a long time. Then the footsteps retreated, the car door slammed, and finally the sound of the motor faded.

When Franck got home from work, he called the Department of the Sea and was told that they knew of no one who had been dispatched to take the turtle. The only sea turtle holding facility was on another island. The official informed Franck that there was now a veterinarian charged with overseeing sea turtle cases, and she put Franck in touch with him. Not long after, the newspaper reported that all the sea turtles in that facility had died because of poor care.

Likely, the so-called turtle expert and his friend had planned to cook Merlin for dinner.

Merlin’s recovery

We constructed an enclosure for Merlin on the fringe reef, and tried to get him used to it. But instead of exploring, he floated in the corner nearest the house in a cloud of fish, looking up at the house. He must have been lonely after so much attention close to us, in his pool.

But as time passed, he began exploring his enclosure and drifting in the middle, finning against the waves. So I tied a coconut frond there for him to hold on to. Once, when high waters lifted him over his fence, he circled it, then swam to the beach.

At sunset, I carried him to the shallows and softly scrubbed him to keep algae from growing on his skin and shell. He had been sick for so long that in the tropical warmth it had become a problem. Merlin followed my movements with delicate touches of his wings and as I brushed his ventral shell, he clutched my hand for support. The delicate, curved bones in his hind fins shaped them like fingers so that it felt, each night, as if a small, human-like creature grasped my hand between his two, with cool, gentle fingers.

When the sea was too high, the waves too exhausting, or the sun too hot on his exposed shell, Merlin stayed in his pool where he was comfortable.

His limbs were filling with muscle and daily he was becoming stronger and more alert. The bones of his wings extended like those of a bird, as he subtly altered their shape to push against the water. His movements were graceful as the flow of water itself. But, while some days he floated lower than others, there had been little change in his buoyancy over the three months he had spent with us.

He wanted to eat almost continuously, and providing him with good food was increasingly problematic. He came with me when I searched for food for him, and when I saw something promising, I carried him down to the reef to see if it interested him. The outings stimulated him and gave him a chance to see his environment, but we discovered no new foods that way.

Pool time

Each evening, I cleaned his pool and changed his water so it would be the same temperature as the sea he had just left. The air was always colder than the sea, so his pool gradually cooled to the temperature of the air. His reptilian body acquired the temperature of his surroundings, and I felt he should not be subjected to a sudden temperature change. But I did not know what the best temperature was. One night, my back was too painful to carry the many bucketfuls of seawater to fill his pool, so Franck said he would do it when he got home.

But by the time he arrived, Merlin had waited an extra two hours, and it was dark. He was very upset and threw a tantrum, beating the surface of his pool with his wings as violently as he could, driving himself into the side, spinning wildly, and thrashing. But Franck had brought a bonito (an oceanic fish) for him, and when I held a piece of it in front of him, he grabbed it. Suddenly, he was thrilled and ate an astonishing number of pieces.

After that, I filled a large serving bowl with a mixture of cubed bonito, several crushed, boiled potatoes, cooked spinach, and lettuce, each morning. A second bowl was heaped with the seaweeds he liked. Merlin consumed the contents of both each day.

Flying in the sea

One morning, when I carried him down to look at some seaweeds, for the first time, he flew along the sea floor, easily following its contours for several metres before slowly rising to the surface. He was too breathless to repeat the performance, but he had finally succeeded, if briefly, in achieving neutral buoyancy.

Hours later, the wind began to rage, and all night long, the atmosphere screamed. I awoke late in the morning, for no birds sang. Monstrous brown waves tore down the bay, wreckage covered the shore, and a thick layer of sand had been deposited far up under the house. Merlin was hiding at the bottom of his pool. His enclosure was gone, and the sea was far too wild to take him out. For several days, he had to stay in his pool while torrential rain fell and the wind howled. He returned to the surface and remained afloat.

I took him out as soon as the sea calmed and found that he stayed in front of the house, so rebuilding the enclosure was unnecessary. When he wanted to eat, he came to the beach and if I did not appear immediately, he came clambering out of the water to find me. So, I transferred the sketches I had done when he was ill onto a board prepared for something else, and started a painting of him right then and there, so I would not have to leave the deck from which I could watch over my precious sea turtle. From then on, he went into the sea each morning, and spent his days playing on the fringe reef.

A watchful animal

At times, he was able to submerge when we searched for his foods, and then he became a different animal. For the first time, I glimpsed the alert, watchful being he truly was. With his wings, he would stroke down to investigate a crevice in the coral, then when he began to rise, he would stroke again, moving on to look into another crevice. But it was never long before he returned to the surface.

Once, I took him with me when I dived down the wall at the drop-off, thinking that he would like the deep, dark water. But he panicked and swam up over the fringe reef and back to the beach by himself.

Often, he played in the waves on the beach. At first, I rushed down to rescue him, gently putting him back beyond the breaking waves, only to see him come surfing up again a few waves later. It seemed that he liked to play where he could touch the bottom. He began surfing on the beach each evening while I prepared his pool for the night, sometimes clambering up towards me. He was always eager to return to his pool as night came.

The veterinarian comes

After a long delay, the government’s official sea turtle veterinarian arrived. I extricated Merlin from his floating coconut frond with difficulty and carried him to the vet, who stood watching on the shore. He was very gentle and his examination was brief. As he set Merlin back in the sea, he told us that Merlin was the healthiest turtle he had seen in custody. Considering how ill he had been, it was the opposite of what he had expected.

We stood talking in the shallows and Merlin stayed nearby, often coming close to touch our legs, seeking attention. The vet was impressed with his freedom, his trusting behaviour, and the way he used the toys we had tied up for him. He said he was glad to know that there were people able to care for these specialised marine reptiles and that he would keep us in mind in the future if a temporary home for a sea turtle was needed. He left Merlin’s release up to us.

Merlin’s character

Merlin began to explore more widely. He discovered an anchor rope floating about fifteen metres (50 ft) up the shore and began going there to play. One day, I noticed a fisherman in an outrigger canoe cruising slowly past him, so after that, whenever I saw him playing there, I took him looking for food so that he would not make it a habit.

But Merlin did not like to accompany me when I searched for his seaweeds, and he became increasingly adamant that I respect his wishes. Though he came passively in the beginning, he began experimenting with various escape strategies. He would swim along while I had my arm around him, but once I let go, he would whip his wing out of my reach and take evasive action with surprising rapidity. When he was especially irritated, he would smack my hand with his wing as I reached out to guide him in the proper direction.

Eventually, he began taking off for home as fast as he could when I dived down to pick some seaweed, and I would have to speed after him and turn the protesting sea turtle around to continue our search. He could be very hard to see since he was often able to swim just beneath the concealing reflections of the surface. Once, he vanished altogether and it was a long time before I saw him climbing up the beach in the distance. There was no doubt about his intentions; every time a wave touched his hind fins, he hoisted himself farther up the beach and eventually, like a little bulldozer, he struggled to the top, where he was partially hidden in shrubbery.

After that, I procured his seaweed by myself. Yet there were still times when we were swimming together that he suddenly flew home alone. No matter where we were, Merlin always knew where home was.

One night, I was giving him a last feeding in his pool. He was a barely perceptible dark shape, and I fed him by feel, enjoying the delicate touch of his jaws against my fingers. Suddenly, he spun around and snapped something off the other side of the pool, which he began wildly shaking. It was a leaf that had fallen—he was remarkably sensitive to vibration. Yet, during the day, leaves frequently fell into his pool, and he paid no attention to them.

At night, if he was approached, or if a light came on, he would assume a protective position. He would tuck his wings tightly over the edges of his shell, arch his neck so his face pointed downward, and extend his hind fins out from his body, fingers spread. Stroking him gently did not relax him.

Merlin’s fish

One evening, I was carrying Merlin in for the night when the extraordinary face of a stonefish flashed past beneath us, just past the place where we came and went from the sea. It was a large one, with seaweed growing on it. It remained in the vicinity for several weeks, rarely moving, even when we went close to watch it.

Merlin’s multispecies cloud of fish was always present and partook of the scattering crumbs when he ate. Yet there was no greedy rush forward in spite of the hundreds of individuals; in deeper water, they filled the volume of a room. The most alert were small silver jackfish. They appeared around me as I put on my gear in the shallows and as I glided out, they surrounded me in formation, with the leaders a metre in front, escorting me to Merlin.

Some of them always came with me when I returned to the beach, a few taking the lead, while others swam companionably around me. They came too, when Merlin and I roamed together, but if he wandered too far away, they would not follow. When looking for him, scanning the water from the shore, I would often see them coming back, which told me the direction he had taken.

Those small animals seemed to form a community in which I was accepted and welcomed, something I had never known, in spite of the time I had spent observing terrestrial wildlife as a wildlife artist. The presence of the stonefish so close to our feeding area was unlikely to be a coincidence. It too was part of the community.

One day, Franck went to fetch Merlin in his kayak when he strayed too far. I was waiting on the beach with Merlin’s fish, and they all went streaming out to meet the kayak when it was still ten metres (32 ft) away! When Merlin was placed back into the sea, they flashed around him like cascading silver coins. And as he raised his wings and surged away, they took up their positions around him. As many as possible clustered against his ventral shell, likely for protection.

A striking incident illustrating the faculties of Merlin’s fish occurred one day when I was walking on rocks lining the shore. His fish came streaming over and milled around in the water below me. They clearly recognised me from under the surface, though they had not seen me there before, and I looked very different fully dressed and standing on the rocks above, than I did when underwater. Those fish were remarkably intelligent.

Part Two: Foraging and taking flight

One morning when I looked out, Merlin had vanished. But I soon caught sight of his pale hind fins catching the light in the turquoise water as he poked through the coral not far from shore. Underwater, his entourage of fish announced his presence, and I drifted closer. Poised on the sand on his wing tips, he was poking his head into holes in the coral, apparently looking for something to eat.

Suddenly, he saw me and froze, alert with wide eyes, and he crept out of sight. I drifted away to avoid disturbing him. He spent the rest of the day on the floor of the fringe reef, languidly looking around and surfacing every four or five minutes to breathe. But by late afternoon, he had tired and lay resting on his coconut frond.

The next morning, he remained submerged most of the time, but by evening he was having difficulty, and the next day he was back on the surface. Another month passed before he was able to dive as he wished. But when he was frightened, he found the strength.

One evening, Franck offered the stonefish a chunk of bonito. For a long pause, there was not the slightest response. Then, moving too fast for the eye to follow, the stonefish shot from its shelter and engulfed the food. Merlin and his fish instantaneously vanished and several minutes passed before he surfaced, far from shore. It was a dramatic illustration of the awareness of those marine animals.

Merlin would also take flight underwater if left alone with other people. His sense of danger was enhanced as night fell, and often we could not discern the reason for his sudden flights away.

One early morning, a whitetip shark of about two metres (6.5 ft) in length, circled me as I picked some seaweed. Then, she glided into the shallows to investigate Merlin, playing on his coconut frond. Two days later, she ascended the drop-off when Merlin was with me, passed less than a metre away, and slowly descended again. Sharks are curious creatures, and she never bothered the young sea turtle.

Further explorations

With time, Merlin began roaming farther. One morning, he disappeared when we were at breakfast and after a frantic search, I launched my kayak. A fisherman was paused in an outrigger canoe some distance along the shore, and since fishermen posed the greatest danger to Merlin, I glided near.

The huge man was gazing intently at something, angling his boat closer, so I approached too. I said “Hello,” and told him that I was looking for my sick sea turtle, hoping that he would understand that a sick one would not be good to eat. He pointed farther on, and there was Merlin, trying to wedge himself into a hole. I was greatly relieved when the man did not object as I stepped into the stonefish-infested coral and hoisted the straying turtle into my kayak. He could so easily have harpooned him right in front of me.

The practice of eating sea turtles is especially unfortunate since it was the French who convinced the Tahitians to use them for food. Before the arrival of the Europeans, the islanders held the animals sacred and did not eat them. The exquisitely evolved reptiles take decades to mature and breed, which is a long time to survive in islands lined with sea turtle hunters.

Fright and recognition

By now, it was often necessary to go looking for Merlin underwater, yet when we found him, he behaved as if he were terrified. This was a puzzle when he was so comfortable with us otherwise. He could hear us coming long before we could see him and flew away, making it hard to find him once he could dive and swim swiftly.

I speculated that it was because of the turbulence of our movements to which he was so sensitive, and our poised, alert attitude, that warned him that he was in the presence of predators about to attack. His body language showed that he was truly frightened when he saw us coming, so I taught him to recognise me underwater by holding him near, so that he could only see my face and hands, then feeding him. Gradually, he learned to recognise me in spite of his alarm when I first appeared. He would relax and come to me.

Moving to a sea pond

By then, he was too strong and active for his inflatable pool, so I deepened a natural depression behind some rocks lining the shore until it filled with seawater. The resulting pond was six metres (20 ft) long, shaded by trees, sheltered from the waves, and floored with white sand. Merlin could neither climb out nor injure himself there. Best of all, wave action provided continuous flows of fresh seawater between the rocks, keeping it perfectly clean. We put him in it after he ate that evening and after a careful investigation, he stayed there contentedly.

He was now able to swim so fast that it was hard for me to keep up with him. Often, I lost him, and had to wait for him to surface to relocate him—he breathed about once every five minutes. He would often take me on a wide circle far beyond the drop-off, then return to our beach, where he hoped, it seemed, to ditch me. There, he would behave as if he wanted to eat, but when I ran to get his food, he would fly off again, and I would have to run to get back underwater fast enough to stay with him.

Complex cognition

Since acts of deception indicate complex cognition (the word used for thinking in animals), this suggests that he had much higher intelligence than reptiles are usually credited with.

Either through exhaustion or affection, Merlin would soon cease his evasive techniques and join me. I would pick seaweed for him and we would roam lazily for a while. Then, off he would go again, a dramatic spectacle, flying fast with strong strokes of his wings, his silver jackfish filling the water around him.

Since he had turned out to be such an interesting little character, I wrote down his story and submitted it to the Tahiti Beach Press, a magazine for tourists and English-speaking residents.

Danger

One day, Merlin disappeared, so I hurried out in the kayak to look for him. It was some time before I saw him surface, and by the time I caught up to him, he was swimming onto a beach a few hundred metres along the shore. I glided up beside him and snatched him from the water before he landed. A Tahitian family was watching from the deck of a house there, so I waved and smiled, explaining that the turtle had been sick and was recovering. The woman called to me, “You’d better keep that turtle at home. We eat sea turtles.”

My goal was for him to resume the normal life of a wild sea turtle as soon as he was able, but he was not yet strong enough. He was spending far too much time on the surface and in shallow water—he still had not ventured into the deep water beyond the fringe reef. He needed more time. Intensely worried about keeping him safe, Franck and I had discussed possible strategies to protect him as he convalesced, but not one was feasible. And he still spent most of his days in front of the house, exploring underwater between the two beaches, playing with his toys, and lying around on the beach waiting for attention.

One early morning, a neighbour with three boys came to fish on the rocks in front of our house. She lived along the shore, and we had often greeted each other on meeting. Merlin was in his pool behind a clump of trees some distance away, and it was not long before the children’s shrieks announced that they had found him. By the time we got there, they were pelting him with rocks. Franck spoke with the boys, while I went to talk to the woman. I explained to her that the turtle was recovering from a serious illness, and asked that she not let the children hurt him. She said that she would not, but it was obvious that had we not been there, she would not have intervened in their assault on him.

Almost back to health

Five months had passed since Merlin came. I worked on the painting of him whenever I had a spare moment. The water around him was finished, and the intricate patterning on his shell, a finicky business using the airbrush, was almost completed.

He was eating more food than ever. Daily, he consumed eight potatoes, mashed and mixed with a bunch of cooked spinach, a head of lettuce, a kilo of raw bonito, a big bowl of seaweed, and three or four eggs. When he swam into the beach and lay looking up at the house, I ran down and sat with him, feeding and caressing him, while his fish flashed about us. Yet he would frantically protest that he was starving in the evenings when I carried him down the stone pathway to his pool. So, he would receive several pieces of fish before I left him for the night. He had grown several centimetres in length since he had come, his skin was like satin, and his limbs were strong.

Two days after the boys’ attack, Merlin had to spend the morning in his pool while I went out to replenish his supply of seaweed; Franck watched over him. Then I unloaded the kayak, fed some seaweed to Merlin, and planted some in his pool. He played in the sea as I made lunch, and when he came to the beach, I went down and fed him again. After we ate, I went to check on him.

But Merlin was gone.

The search

I searched from one end of the bay to the other for the rest of the day. As night came, the sea was still as glass. Merlin’s head breaking the surface would be visible far away, and I made one last search from the head of the bay to the ocean. Above the mountain, the full moon arose, while to the west, the luminous mirror perfectly reflected the sunset sky. As I turned to look across the glowing expanse, a head the size of a child’s broke the surface just in front of the kayak—a sea turtle of enormous size. I heard him breathe, then he submerged, leaving only a shining circle of turbulence.

I paddled home, amazed in the moonlight, wondering if Merlin could have left for the ocean.

The next morning, Franck and I went out at dawn to search as far as the ocean before the wind arose and ruffled the surface, obscuring the view of a surfacing turtle. The waves pounding the barrier reef were daunting; there was no way that Merlin could cope with life in the wild yet.

And why had he not come home to eat? In my experience rehabilitating wild animals, their behaviour patterns did not change suddenly, but evolved gradually as they grew more capable and expanded their horizons. I had a very bad feeling about Merlin’s sudden disappearance.

In the afternoon, I walked along the road, talking to the neighbours. Since Merlin usually swam on the surface along the shallow fringe reef, he would be visible to anyone looking out from their seaside home. Some of the people were friendly, but some just laughed. One made signs of eating. Some were hostile, especially the woman who had told me to keep Merlin “at home.” Never had the racism there been thrown into such a stark light.

At the neighbourhood store, the owner told me that the day before, friends of his had caught the sea turtle and eaten him. I asked if I could see the shell to confirm the identity. The man told me that he would try to get the shell, and I should come back the next day. Further enquiry revealed that his throat had been slashed, and he had been delicious.

I walked back along the shore in case his shell had been thrown out around any of the shacks, but found nothing. At the store the next day, the man told me dismissively that the shell had been thrown out with the garbage. It was gone, so was the turtle, and he obviously expected that I would be gone too.

“Well,” I said, “the vet thinks that the turtle’s medication could be dangerous to someone eating him. . . His heart could just... aaahhhhh... stop.” The man, a good 300-pounder, stopped grinning. His eyes grew round, and so did his mouth. “So, anyone who ate that turtle should go to the doctor right away,” I finished. The man changed the subject and turned to other things. I left.

Media attention

It was then that my story about Merlin appeared in the Tahiti Beach Press, and on the same day, a whole page of La Dépêche, the daily newspaper, was devoted to Merlin’s fate. “Merlin, Disappeared by Enchantment,” the headlines read. And the police were actually at the beaches checking boats to make sure that no fishermen were bringing sea turtles back with them.

Since I was referred to in the article as a “naturiste” which means “nudist” in French, instead of a “naturaliste,” men were phoning up wanting to meet me. Others called me to say that they had seen Merlin in different locations near and far. The last thing I wanted was to be seen out in public, but since our car had broken down, I was obliged to spend much of the time out on my bicycle. With mask, snorkel and fins in my basket, I pedalled as fast as I could to investigate all the reports. When I came home, in an anguish that could not be quenched, unable to rest, I set off in the kayak to search for Merlin, as if to stop would be to give up on ever seeing him again. But his head never appeared at the surface, as far as I could see in any direction, no matter how long I looked.

One day, I walked along the shore in the early morning and sat down in a wild place from which I could survey the entire head of the bay. On the rock seawall, rats were pursuing their affairs. One, I idly noticed, had skin problems. Another was very young. About half an hour later, the rat with the skin problems emerged from the forest. He had actually found a plastic package half full of cookies. As he dragged the cumbersome thing along the rocks above the seawater, he suddenly noticed me. Startled, he jerked his head up, letting go of his prize. The bag of cookies tumbled down the rock wall and into the sea.

He watched it sink and took a few steps towards the water. I could see the moment he realised the futility of trying to rescue them—there was a long pause. Then he went back the way he had come and disappeared. It was like an echo of my tragedy. I slowly gave up my search for Merlin, but it was a year before I could bear to finish his painting. ■

Read more about Merlin and the stories of three other sea turtles, with additional insights into their remarkable intelligence and sentience, while facing the ever-present perils posed by hunters. Buy the full ebook or paperback, Merlin: The Mind of a Sea Turtle, by Ila France Porcher at: amazon.com.