Dreaming of diving off an uninhabited tropical island? Doing this by liveaboard boat is one approach, but here, on Bangaram Island, one can live the island dream while staying on the island itself, which has enough infra-structure to make it comfortable.

Contributed by

They are off-limits even for the original inhabitants who have been trying to return for many years.

The middle archipelago of islands is the Maldives—an island nation well known to divers. At the northern end are the Lakshadweep islands, formerly known as the Laccadives. All of the islands rising out of the sea from this plateau are low lying coral atolls with associated sandbanks and other coralline structures.

The coral growth has kept pace with land sinking and sea level rises, which have been happening for thousands of years giving, for divers, sheer vertical walls, shallow inter atoll bridges along with sandy lagoons to enjoy. Of course, the coral doesn’t grow above the level of the sea surface; for island formation, storms or earthquake uplift are needed. Storms wash coral debris onto the top of underwater coral, but storms also mean some islands periodically disappear. The Chagos-Maldives-Lakshadweep Archipelagos are in a dynamic state of flux.

I went diving in the Lakshadweep archipelago on Bangaram Island. India has been very cautious in allowing “outside” influences in this archipelago—firstly, to protect the local native culture, and secondly,to protect the fragile ecosystems.

India—to visit or just dive?

Never having visited India before, I chose to combine the diving trip to Bangaram with a visit to parts of the Indian mainland in one trip. I didn’t know exactly what the diving would be like, as it has had little or no coverage. Would I regret not spending all my available time underwater?

I first heard about diving on Bangaram when I talked with two of the owners (Michael and Badu Dominic) of the family-run Indian CGH Earth resort group of environmentally-friendly hotels, and found out they were both divers. The group owns the resort on this little known island. They highly praised the diving, so my excuse to visit India was sealed.

Getting to Bangaram from England involved first a transfer stop in Mumbai, or Bombay, as everyone local still calls it. I booked this with a morning arrival and a next day internal flight to Cochin (or Kochi in other speak) so had a day to visit the city, and did the same on my return.

Mumbai is a crowded, frantic, hectic, busy city that is fantastic. It’s way too big and too congested to see more than a tiny fraction of it in two days, but one still can get a taste of the place. The first thing I noticed was the relaxed friendliness of the people, and that most spoke at least some English. Then, I noticed the slow rush of vehicles to get somewhere, as I tried to walk across a road. As a pedestrian, you quickly learn to weave amongst the cars.

With a car and a guide—which is essential—I crammed in visits to the Gandhi museum, the “Gateway to India”, various religious shrines including Elephanta Island, a riverside laundry, various street markets and more. Yes, there was poverty. Yes, people were begging, but it never seemed oppressive —people were generally happy. Yes, some streets were litter-strewn, but seldom worse than England could be with our new rubbish “maybe collect” policies. While, on the whole, I was pleasantly surprised how tidy much of the city was.

I would love to go back for a longer stay. At least a few days in a big Indian city should be on one’s “to do” list.

Cochin is the gateway to the Lakshadweep islands. I went via Mumbai, but direct flights from some European cities, from other eastern countries and other Indian cities, do exist. Cochin is famous for its Chinese fishing nets, to be seen in any travel book of the area, and they do still exist and work. As in Mumbai, I had two nights, one each going and returning. The town is larger than maps seem to show it, and it’s spread over several islands. I stayed on the seafront, near Fort Kochi, just a few minutes walk from those nets, so I did manage to get to see them as well as the fish market stretching along the beachfront.

Getting there

Flying to Agatti was on Kingfisher Airlines—an airline reputed to have more reliable service than the ten-seater plane. Those of us going on to Bangaram were escorted out of the small airport to a thatch-roofed, open waiting area for passport and permit checking before seeing our bags manhandled over the beach to a little movable floating dock, which was pulled over to our boat moored just offshore. Following our bags, our group of newly arriving visitors sat back for the hour-long journey to our very own enchanted, tropical island surrounded by a turquoise blue sea.

Bangaram Island is officially classified as uninhabited, with only the 80 or so resort staff—most of whom come from one of the other islands—and up to 60 visitors at any one time. So, does one really get to claim he or she has spent vacation time on an uninhabited island?

Accommodation is provided in one of 30 double bed chalets, each with shower and toilet, mini-bar fridge and enough space that a cat wouldn’t hit its head if you had one to swing, and electrical outlets that maintained power throughout the day and night.

Communal facilities included a library and games room, dining hall used for breakfast and lunch, beach bar, plus the water sports centre and, the all-important, diving centre.

No roads, just paths, no motor vehicles, no TV, not even mobile phone coverage—so, it is a location for relaxation.

Dinner was served under the stars, buffet style, with a good variety of entrees always including a choice of two or more fish, chicken, or other meat and various vegetable dishes, plus a couple of types of rice. We had barbecued tiger prawns one evening that was REALLY difficult not to overindulge in.

The food here, as in all the group’s offerings, was a little bland for me, probably cooked for the more normal Western visitors—not one used to cooking his own rather spicy concoctions at home. The food suited my partner just fine.

The beach bar was the only source of alcohol in the Muslim Lakshadweep islands, where it was illegal otherwise. So, an after-dive beer or wine with dinner was available.

The resort was very environmentally conscious with rainwater collection and storage for most water needs. The used water was treated and reused for watering plants.

Electricity was generated with solar cells with battery storage and diesel generation was only used late at night when batteries ran out. Plastics were discouraged, and any that did come to the island were returned to the mainland for recycling.

Equipment matters

Being here for the diving, my partner and I visited the dive centre in the morning after arrival to sort out hire of equipment as we had only brought wetsuits, masks, camera equipment and dive computers with us. Long flights and weight limits had put constraints on what we could bring with us gear-wise. But bringing our own wetsuits proved sensible as the hired ones were shorties—fine, if you keep swimming, not so good if you take your time, even in the 30°C water.

Bangaram Island is inside a 10 km by 8 km atoll, joined by one other similar sized uninhabited island, Tinnakara, plus two very small ones, Parali-I and Parali-II.

Looking at local charts, it appeared as if the areas outside the surrounding fringing reef dropped to depths of over 1000 metres on three sides of the reef. In places, these depths reached up to a couple of kilometres offshore. Others were relatively near, but deep depths were generally found only after more gently sloping contours.

On the side facing Agatti, a wide sandy bank bridged the two islands at 11 metres depth. All of this is important for the coral, as you will see later.

I asked Sumer Verma, the dive centre owner, about his diving customers. He said that over half were repeat visitors from many parts of the world. In general, they were vacation divers, often ones wanting to chill out with the island life. Some had bad experiences elsewhere (evidently many from a first experience that went wrong in the Red Sea). Others, such as us, needed to “get wet” while on a wider visit to India.

All the diving took place from a slow hard boat, similar to the one that brought us to the island. It had bottle storage racks, wooden benches, a proper toilet inside and an insulated sunroof. So, it was comfortable for up to the 12 divers that it could carry, but did not meet the standards, or needs, of Red Sea day boats, which have to cover longer distances. The dive boat did carry an oxygen kit, radio and life vests.

Being a slow boat, it did save on fuel—a positive environmental consideration for this very environmentally aware resort—but it meant that trips to all the dive sites along the outside of the fringing reef took 40 to 80 minutes to reach.

Site selection was made in the morning, dependant on the weather but mostly on the experience levels of those who turned up. The island life was relaxed; guests might or might not do what they planned the evening before, making for awkward dive planning. This was of little consequence except for photographers who wanted to set up lenses.

The boat had no provisions for photographers; not even a rinse tank was available when I was there, let alone a flat dry area for setting up. However, the fact that the dives took place in a relaxed atmosphere with 30°C water, time limits of an hour and a none too frantic pace led by the dive guide made up for this problem.

Remnants of an old wooden shipwreck, the Princess Royal, within the lagoon can be found, but in practice, it is coral reef diving that is the primary draw, as the wreck has only a few exposed timbers.

Most chosen sites were in the low 20-metre depth range with a few a little less. One site, “The Grand Canyon”, was a narrow fissure extending below sport diving limits.

Shallower sites were available, and the first steps in training were done within the sheltered lagoon. Looking at the local charts, there should have been some stunning vertical walls to see. However, since they start at about 30 metres, these are not on offer.

All dives started with a backroll, then a surface meeting to exchange OK signs, and finally the group descent. The dive sites were often on gentle sloping reef faces, so divers started shallow before finning deeper. Dives then meandered back up, giving excellent multilevel profiles for those hour-long dives.

The surface interval of 60 to 90 minutes was spent relaxing on the boat with fresh pineapple slices and cakes, which set us up for the second dive that had us back at the resort by 2:30 for lunch.

Afternoons were spent unwinding on the beach, snorkelling, kayaking, going deep sea fishing, getting an ayurvedic treatment or going for a walk—it’s a small island with enough to do if you’re not expecting a raving disco or late night clubbing.

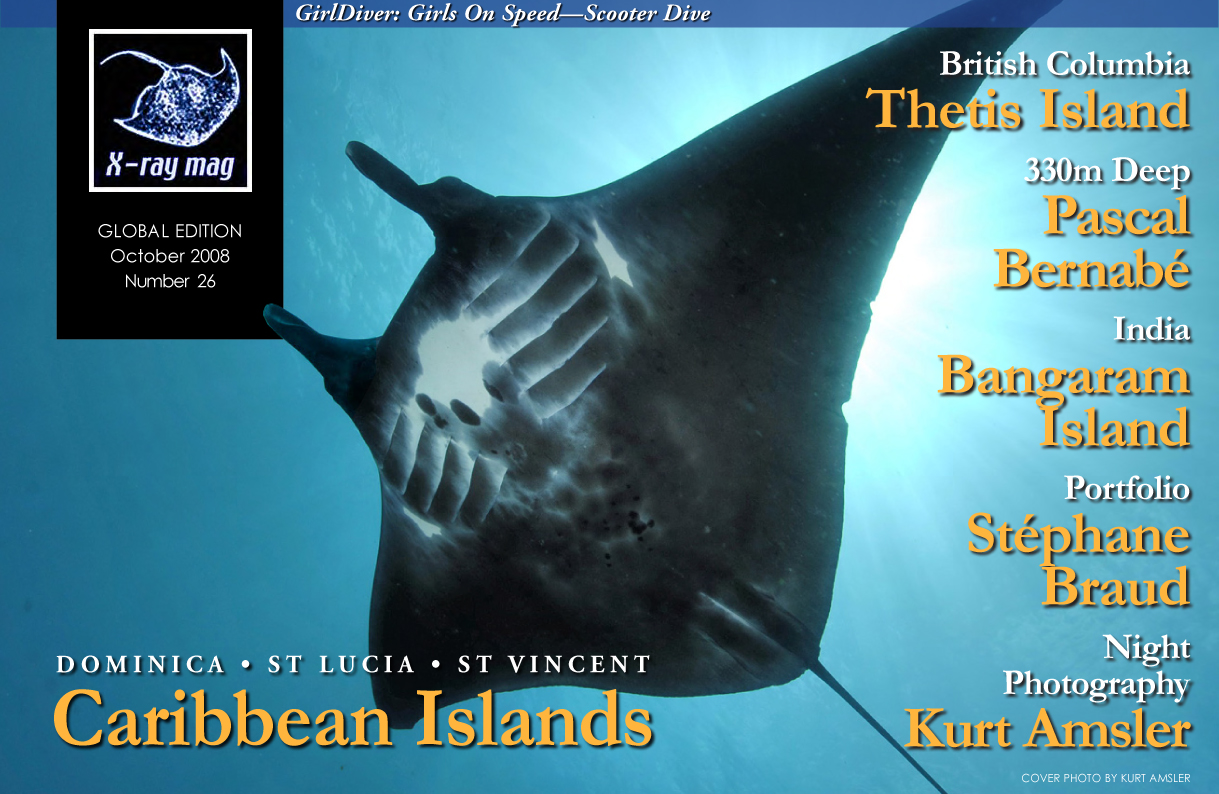

A number of sharks and a few large rays were seen on Manta Point, but that was the day before my dive. Isn’t it always just before or after your dive?

On my dive, marine life was limited to a few hawksbill turtles, fish of the oriental sweetlips variety at cleaning stations, eels popping out of holes, anemone fish doing their thing, and the rest of the expected coral reef fish and invertebrate life hiding in holes.

Shark sightings arose at Entrance Point with a couple of nurse sharks sleeping under a ledge. We saw a ray and a clutch—if that’s what you call 15 or more together—of spiny lobster at Bangaram Reef, cushion stars, giant clams, bannerfish, trevally, wrasse, garden eels, butterflyfish, parrotfish and more at many if not all the sites. Yes, fish life is reasonably good. A guide book to the Maldives will work relatively well here with some minor changes.

The big stuff is less common and tends to visit only in November-December with the cooler waters. Manta ray cleaning stations haven’t yet been found, and the sightings are few and only made during those cooler months.

Since most of the clientèle were vacation divers, the organization of the diving for them adhered to a policy that had the divers following the guide who led the group. Strict safety was emphasised. The chance to stay and watch animal behaviour was limited if the group lost interest, but interesting animals were pointed out during the dive giving everyone an opportunity to see marine life. More experienced divers were provided with their own guide on the same site, if numbers worked out.

Warm waters

The warm, 30°C water made for pleasant diving, but the downside was the presence of coral bleaching, with much of the hard coral dead. Small patches and stands of good coral were present on every dive and recovery was slowly happening.

The warming effect of the 1998 El Niño affected the whole of the Chagos-Maldives-Lakshadweep submarine mountain range. Recovery seems much slower here at Bangaram. It is possible that the Maldives made a quicker recovery due to stronger, cooler deep ocean currents. The top of the mountain range around Bangaram atoll and

Agatti is both large and shallow, so the sun warms the water, while the prevailing currents—being from the west—are possibly pushing the newly warmed water over the reefs slowing regeneration.

Agatti is at the southwestern side and suffered less damage during El Niño. Recovery seems to be better. We did get below a thermocline at one point and found better coral condition. The poor coral is a deterrent to making the trip, but it shouldn’t be a show stopper for an occasional diver, or for anyone making this excursion a part of seeing more of India.

In addition to diving on Bangaram Island, diving is also available on Agatti and Kadmat Islands, which I wasn’t able to try. Both of these islands supposedly have less coral bleaching yet somewhat similar coral diving. Accommodation on both of these islands is more basic. Kadmat is a few hours’ boat journey after arriving in Agatti.

None of the islands and nearby seas are really fully explored. It is still relatively virgin territory, with the possibility of good new sites yet to be discovered.

Did I err?

Having come to the end of my stay on Bangaram, could it be said that I erred in choosing to make my first trip to India a mix of diving and visiting some of the mainland? No. The other guests and I enjoyed the dive sites of the island, and the resort was great, but the diving wasn’t world-class. The trip as a whole was in the world-class category and was enhanced by time spent underwater.

Cochin and Mumbai were gateways worth seeing. The remainder of the time was spent visiting a little of the state of Kerala beyond Cochin.

Kerala

Kerala is coastal— well known for its coconut palms growing along its 1000 plus miles of interconnected lakes, rivers and canals that make up the backwaters. Further afield are long stretches of sandy beach, rugged mountains, tea plantations, agricultural areas, and historic and religious centres of many flavours.

This isn’t the article for extensive coverage of all the attractions, but a short mention might show why a combined diving and sightseeing trip is worth considering. I only just scratched the surface of what there is to see in this small green state of India.

The backwaters are on the doorstep of Cochin. I went to Coconut Lagoon, accessible by boat, looking first at what could be seen by land, with nature and village walks. Then, I spent a night out on a Kettuvallam (Rice Boat) built as a houseboat.

These houseboats varied in what they offered, but most will effectively offer a high class private floating hotel room with full amenities—OK, a private bedroom, toilet and shower with meals cooked just for you. They ply the waterways allowing easy viewing of life as the locals live it. Locally, people often travel by canoe or boat for nearly everything—to the rice fields, for fishing, even shopping. In a way, you become some part of this world.

The backwaters themselves are interesting environmentally, as much of the adjacent land is below sea level with dykes holding the water back. Seawater is let in seasonally to flood the waterways, which helps to control the water hyacinth invasion.

It’s an area undergoing economic changes with coconut palms replacing rice fields in some places. More tourists visit now with the houseboats, and land reclamation is taking place. The area grows a lot of coconuts with local home industries producing coir products, spinning the coconut fibre into twine, weaving traditional door mats, and more.

The region is worth seeing maybe sooner rather than later. There’s just too much to see—this is the only real problem.

The beaches in Kerala are—well, beaches—long white sandy places with water at one edge—less crowded, less touristy than Goa just to the north and lacking the wild nightlife. If you want to continue the Bangaram style beach life, it’s worth considering coming here, as I did for a moment at Marari Beach. Not being much of a beach bum, I took a three-hour tour by tuk-tuk to see other fishing villages.

Driving inland, coconuts give way to rubber tree plantations and pineapple farms in this agricultural region; then, impressive mountains become apparent as foothills become steeper, valleys spread out below, and the road switchbacks up sheer cliffs. Near the top, one can find tea plantations sprouting, spices growing, forests and nature reserves.

I made it up to the tropical rainforest and Periyar Tiger Reserve near Thekkadi to visit a tea factory as part of the drive. No tigers were seen at the reserve, not that it was really expected, as only about 12 wild ones are left. I took a long hike in the reserve, then a boat ride on the lake, which shows off the wild elephants, water buffalo, monkeys and deer.

The reserve is doing its thing on the environmental side—converting local tribal people from poachers to game wardens and tourist guides. The park boasts a diverse flora of over 2000 species of flowering plants, many of which are endangered, including many species of orchids, grasses and trees along with the diverse animal life.

I found these explorations great fun as well as educational but wondered what families, and in particular, what kids would think about it all. Was it very much an adult trip? So, I asked a few English families with kids what they thought. I was surprised by the responses, summed up by one ten-year-old, who said that their Kerala trip—not dissimilar to mine—was the best holiday she had ever had. She said, “It has the climate, colour, food, friendly people, things to do, beaches, mountains and animals,” and she didn’t want to ever go home.

Environmentalism

Taking this trip happened slightly by accident following a certain conversation about a hotel’s environmental endeavours. The CGH Earth group are proud of what they are trying to do, something beyond the normal. So, what did I find when I visited?

First, conservation happens in the background, something a guest finds out only by asking, and I was asking. Seeing the practice in action was impressive. There were a variety of initiatives at different locations, each hotel looking at its local situation to minimise impact for that location. They were not using a blanket, unthinking “one-fits-all” approach.

All the hotels did substantial recycling. Plastics and metal cans were sent to commercial centres, organics composted using either anaerobic digesters or earthworms—sometimes for fuel—and grey water was used for gardens.

These days, ‘recycling’ is often just a catchword for governments or establishments to duck behind. Here, at Spice Village, it was impressive seeing over 70 good size wormeries lined up taking compostable waste with the output used on the hotel gardens or in mushroom growing bags.

Coconut Lagoon used both worms and heated anaerobic digesters (heated by burning other waste) to produce methane used for cooking stoves. Tree cuttings might be chipped for mulch or composted.

Varied rainwater catchment and storage systems were in use. The reverse osmosis water purification plant was impressive at one hotel. Others used less water, so had simpler smaller systems.

The solar cells on Bangaram with battery backup were necessary as no supply grid existed. On the mainland, some electricity might be solar cell generated, but grid supply was often used, as this helped to support supply to the local communities who otherwise wouldn’t use enough to justify making it available.

Local materials were used in buildings—indeed, the older buildings had been rescued, moved and rebuilt. Local people filled most of the staff positions. The Kettuvallam boat was commissioned to be built using the traditional practice of stitching planking together with coir twine—a building practice that is now being lost as nailing is cheaper.

The CGH Earth group is doing an excellent job with eco-tourism. It’s almost worth visiting just to see how tourism can turn “green”, and they accept it as an ongoing, evolving practice. ■

Both the India Tourist Office and CGH Earth Group went out of their way to be helpful in organizing this trip. The author and X-RAY MAG would like to thank both.

Links:

CGH Earth www.cghearth.com

Government of India Tourist Office

www.tourisminindia.com

Ministry of Tourism

www.incredibleindia.org